|

|

Times Square

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st July 2014). |

|

The Film

Times Square (Allan Moyle, 1980)  Predominantly set in and around a pre-Giuliani Times Square, Allan Moyle’s Times Square (1980) focuses on the relationship between two teenaged girls from different social backgrounds: free spirit Nicky (Robin Johnson), fifteen years old, is homeless; thirteen year old Pamela (Trini Alvarado) is the daughter of City Commissioner David Pearl (Peter Coffield), who is intent on cleaning up Times Square. The two young women meet in the New York Neurological Hospital after Nicky has been admitted, presumably for her own safety, and Pamela has been taken there following an apparent breakdown. Nicky soon persuades Pamela to run away, to flee her sheltered life for the freedom of Times Square, where the pair soon establish a punk band, The Sleez Sisters, that is championed by radio DJ Johnny LaGuardia (Tim Curry). Meanwhile, David desperately tries to uncover his daughter’s whereabouts. Predominantly set in and around a pre-Giuliani Times Square, Allan Moyle’s Times Square (1980) focuses on the relationship between two teenaged girls from different social backgrounds: free spirit Nicky (Robin Johnson), fifteen years old, is homeless; thirteen year old Pamela (Trini Alvarado) is the daughter of City Commissioner David Pearl (Peter Coffield), who is intent on cleaning up Times Square. The two young women meet in the New York Neurological Hospital after Nicky has been admitted, presumably for her own safety, and Pamela has been taken there following an apparent breakdown. Nicky soon persuades Pamela to run away, to flee her sheltered life for the freedom of Times Square, where the pair soon establish a punk band, The Sleez Sisters, that is championed by radio DJ Johnny LaGuardia (Tim Curry). Meanwhile, David desperately tries to uncover his daughter’s whereabouts.

Times Square was director Allan Moyle’s second feature film, after The Rubber Gun (1977). Although he has directed screwball capers (The Gun in Betty Lou’s Handbag, 1992) and science fiction thrillers (X-Change, 2000), a number of Moyle’s subsequent films would continue to explore some of the themes contained within Times Square: Moyle’s interest in youth culture, the concept of ‘resistance through ritual’ and the potential of music to liberate adolescents, to offer them a voice that cuts through the hegemony of (repressive) adult voices. Moyle’s films frequently featured marginalised young characters; some of these characters exhibit self-destructive behaviour. Based on an unpublished novel by Moyle, Pump up the Volume (1990) features Christian Slater as loner Mark Hunter, the young head of a pirate radio station. Mark’s pirate radio broadcasts offer an outlet for the frustrations of this isolated young man: at school, he is seen as a quiet outsider; but by night, on the airwaves (and under the nom-de-guerre of ‘Hard Harry’), he expresses his strong anti-authoritarian views about his local community and the high school at which he studies, provoking the ire of the principal. Harry finds himself implicated in the suicide of a fellow student. Moyle’s later Empire Records (1995) covers similar territory, focusing on the young employees of an independent record store, Empire Records, as they try to fight the store’s seemingly inevitable fate: that it will be sold to a large chain. The film’s narrative takes place over a single day, as the employees of Empire Records discover more about one another, and the ways in which their work at the store enables them to function as part of a surrogate family. Like Times Square, Empire Records climaxes with a defiant and celebratory ad-hoc musical performance (in Empire Records, on the top of the store’s roof; in Times Square, on top of one of the cinema marquees in Times Square itself).  Times Square was produced by Robert Stigwood. Along with Michael Schultz’s film Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), Jane Wagner’s Moment by Moment (1978) and Staying Alive (Sylvester Stallone, 1983), Times Square marked one of the few financial disappointments of the film production arm of the Robert Stigwood Organisation. With interests including music publishing, theatre and film production, Stigwood’s business had almost thirty divisions by the end of the 1970s, and Stigwood was one of the leading entrepreneurs within the landscape of popular entertainment. Within the world of cinema, by 1980 Stigwood had experienced success with Grease (Randal Kleiser, 1978), Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977) and Stigwood’s first film production, Jesus Christ Superstar (Norman Jewison, 1973). On the set of Times Square, Stigwood reputedly clashed with Moyle: presumably buoyed by the successes of Saturday Night Fever and Grease (and their respective double album soundtracks), Stigwood wanted to cut the number of dialogue scenes, so as to insert more musical numbers, with the aim of releasing a double album to accompany the film. Moyle left production before the film was completed, and Stigwood completed the film the way he wanted it to be completed. Moyle did not return to filmmaking until almost a decade later, with Pump up the Volume. Times Square was produced by Robert Stigwood. Along with Michael Schultz’s film Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), Jane Wagner’s Moment by Moment (1978) and Staying Alive (Sylvester Stallone, 1983), Times Square marked one of the few financial disappointments of the film production arm of the Robert Stigwood Organisation. With interests including music publishing, theatre and film production, Stigwood’s business had almost thirty divisions by the end of the 1970s, and Stigwood was one of the leading entrepreneurs within the landscape of popular entertainment. Within the world of cinema, by 1980 Stigwood had experienced success with Grease (Randal Kleiser, 1978), Saturday Night Fever (John Badham, 1977) and Stigwood’s first film production, Jesus Christ Superstar (Norman Jewison, 1973). On the set of Times Square, Stigwood reputedly clashed with Moyle: presumably buoyed by the successes of Saturday Night Fever and Grease (and their respective double album soundtracks), Stigwood wanted to cut the number of dialogue scenes, so as to insert more musical numbers, with the aim of releasing a double album to accompany the film. Moyle left production before the film was completed, and Stigwood completed the film the way he wanted it to be completed. Moyle did not return to filmmaking until almost a decade later, with Pump up the Volume.

One of the aspects of the film that Stigwood downplayed was the lesbian relationship between Pamela and Nicky (see Fink, 2011: 62). Although subtle aspects of this are still evident within the finished film – notably when Nicky has a major meltdown after seeing Pamela with LaGuardia (and presumably experiencing, wrongly, pangs of jealousy over the friendship between Pam and the DJ) – in the final cut of the film, the relationship between Pam and Nicky may be read as nothing more than a very close friendship. (Writing about Times Square’s coded depiction of a lesbian relationship, Maria San Filippo compares the film to Annette Haywood-Carter’s 1996 film adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ Foxfire; Filippo, 2013: 139.) Some commentators on the film, including Marty Fink, have suggested that the lesbian relationship between Pam and Nicky is another aspect of their subversive ‘interclass relationship that empowers them to quite effectively speak out against politicians and developers in order to preserve the area [Time Square]’ (ibid.: 62). Despite the problems he experience with Stigwood’s interference, Moyle has ‘expresse[d] his relief that the film was even made, simply for its having captured what the area used to be like before it became “like Disneyland”’ (Moyle, quoted in Fink, op cit.: 62). From the opening moments, the film foregrounds its Times Square setting. Accompanied by Roxy Music’s ‘Same Old Scene’, the opening sequence contains a high-angle shot of the area, followed by street level shots of Times Square and its inhabitants. The names of the cast and crew appear in lights, as on an iconic Times Square marquee. We are shown glimpses of life in Times Square before we are taken to an alleyway, where Nicky, wearing a leather cap and a leather jacket covered in pins, plays an electric guitar whilst sitting on the bonnet of a car. She is soon told to move on by a woman who exits a building (presumably a disco) leading on to the alleyway. ‘Your playing’s shit’, the woman asserts, ‘and that’s the boss’ car’. In response, Nicky smashes the headlights of the car before running away.  Nicky’s introduction is placed in juxtaposition with the introduction of Pamela, underscoring the differences in terms of social background between the two girls. Pamela is introduced at a press conference in which her father, City Commissioner David Pearl, outlines his desire to clean up Times Square. He is introduced as ‘a young lawyer with a long list of crusades’, the latest of which is ‘to renew New York’s finest and most famous landmark’. ‘The question we want to ask ourselves today’, Pearl declares in his speech, ‘especially those of us with children, is this: do we want to live in an X-rated city?’ Pearl then goes on to illustrate his point by relating an anecdote about his daughter’s fascination with Times Square. However, Pamela is deeply embarrassed by her father’s exploitation of his relationship with her in order to reinforce his rhetoric, and she runs away from the auditorium, hiding in one of the public bathrooms in the building. Nicky’s introduction is placed in juxtaposition with the introduction of Pamela, underscoring the differences in terms of social background between the two girls. Pamela is introduced at a press conference in which her father, City Commissioner David Pearl, outlines his desire to clean up Times Square. He is introduced as ‘a young lawyer with a long list of crusades’, the latest of which is ‘to renew New York’s finest and most famous landmark’. ‘The question we want to ask ourselves today’, Pearl declares in his speech, ‘especially those of us with children, is this: do we want to live in an X-rated city?’ Pearl then goes on to illustrate his point by relating an anecdote about his daughter’s fascination with Times Square. However, Pamela is deeply embarrassed by her father’s exploitation of his relationship with her in order to reinforce his rhetoric, and she runs away from the auditorium, hiding in one of the public bathrooms in the building.

Tim Curry’s Johnny LaGuardia is in many ways the film’s Greek chorus, commenting on Nicky and Pamela’s adventures in his radio show. (In some ways, his function within the film may be compared to that of the radio DJ played by Lynne Thigpen in Walter Hill’s The Warriors, 1979.) Curry plays LaGuardia as a somewhat depressed, disillusioned man, who perceives The Sleez Sisters (as they come to be known after the formation of their punk band) as an antidote to the apathy and conformity that he sees about him. When Pearl later hears a broadcast from LaGuardia, he angrily asks, ‘When is this thing [LaGuardia’s show] on?’ Pearl’s assistant replies: ‘Four am. Luckily, who’s listening to him?’ In his introduction, LaGuardia dramatically alludes to both Dragnet and The Naked City on his radio show, humming the theme from Dragnet before asserting, ‘There are eight million stories in the big city. People say I have a bird’s eye view, perched up here, night after night, looking down into the throbbing, pulsing, mainline veins of the city’. He has received a letter from Pam, which he reads on air: she refers to herself as a ‘zombie girl’ and declares that her father ‘expects me to be happy, but I’m clumsy and ugly’. LaGuardia responds sympathetically, telling the anonymous letter-writer, ‘You have something very special inside you, young lady: a seed that contains your unique self. You must nurture that seed’. Pam and Nicky are both admitted to the New York Neurological Hospital, where they share a room – to the chagrin of Pam’s mother, who wants her daughter to have a private room. There, both girls are exposed to a medical profession that proves to be less sympathetic to the two adolescents’ alienation than LaGuardia’s DJ: when Pam asks, ‘Am I going crazy’, a doctor tells her simply that ‘Every boy and girl, at some point in their growing up, suddenly their body begins to manufacture hormones, lots of them [….] It’s a big shock to the system’.  Nicky offers an alternative to the medical treatments that Pam is offered. Nicky tells Pam that ‘I don’t expect to live past twenty-one. That’s why I got to jam it all in now, you know?’ Although to the viewer of the film, Nicky’s behaviour, even at this early stage of the film, is all too obviously reckless and self-destructive – something which will become increasingly evident to Pam as the narrative develops – at this point in the picture, Nicky’s anti-establishment tone resonates with her roommate. Nicky advises Pam not to take the pills she is offered: if she does, Nicky asserts, she will ‘lose all your fight; and your fight is all you got’. Later, after Nicky has persuaded Pam to flee with her in a stolen ambulance, the two girls hiding out in a vast abandoned warehouse, LaGuardia declares on air that he has seen the girls’ medical reports and ‘There’s nothing medically wrong with either one of you [….] Either those doctors don’t know what they’re doing or they’re lying through their teeth’. Pam soon establishes contact with LaGuardia, sending him a letter which he reads on air, declaring ‘I am not kidnapped: I am me-napped, I am soul-napped, I am Nicky-napped, I am happy-napped’. Nicky offers an alternative to the medical treatments that Pam is offered. Nicky tells Pam that ‘I don’t expect to live past twenty-one. That’s why I got to jam it all in now, you know?’ Although to the viewer of the film, Nicky’s behaviour, even at this early stage of the film, is all too obviously reckless and self-destructive – something which will become increasingly evident to Pam as the narrative develops – at this point in the picture, Nicky’s anti-establishment tone resonates with her roommate. Nicky advises Pam not to take the pills she is offered: if she does, Nicky asserts, she will ‘lose all your fight; and your fight is all you got’. Later, after Nicky has persuaded Pam to flee with her in a stolen ambulance, the two girls hiding out in a vast abandoned warehouse, LaGuardia declares on air that he has seen the girls’ medical reports and ‘There’s nothing medically wrong with either one of you [….] Either those doctors don’t know what they’re doing or they’re lying through their teeth’. Pam soon establishes contact with LaGuardia, sending him a letter which he reads on air, declaring ‘I am not kidnapped: I am me-napped, I am soul-napped, I am Nicky-napped, I am happy-napped’.

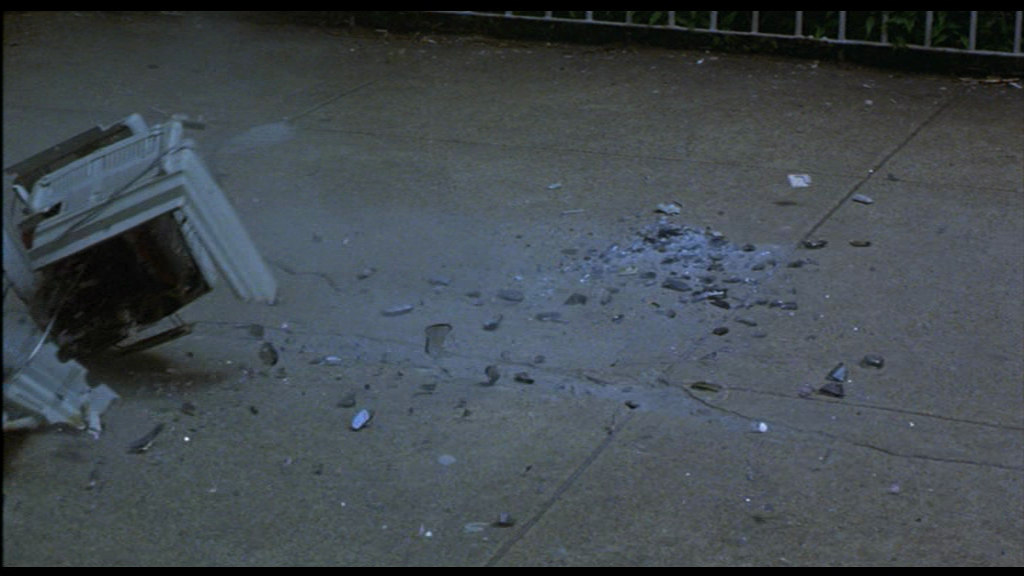

LaGuardia later has The Sleez Sisters play live on his show. Pearl becomes aware that LaGuardia is in contact with Pam, and he threatens the DJ. However, LaGuardia refuses to reveal their whereabouts and continues to celebrate their escapades on his radio show. When Nicky and Pam begin to throw televisions from the tops of tall buildings in and around Times Square, an act that Pam initially describes as one of Nicky’s ‘best ideas’ but later realises is spectacularly dangerous and reckless (‘Nicky, we’re gonna crash somehow [….] We’re lucky we haven’t hurt someone yet’), LaGuardia eggs them on, depicting the act as a symbolic form of resistance: ‘Apathy, banality, boredom, television’, he intones on his radio show as we see a montage of the girls throwing televisions from the rooftops, ‘But a new iconoclast has come to save us. It’s The Sleez Sisters, Nicky and Pamela. Go to it, girls [….] Do anything you want. Keep doing it, for us stay-at-homes. Let it be passionate, or not at all’. Eventually, the astute Pam sees through LaGuardia’s exploitation of the girls – though it’s clear that he is clearly sympathetic towards them, as they live a life of freedom about which he can only dream. ‘You only care about yourself, you faker’, Pam tells LaGuardia. ‘I give myself away, every day, for a living’, LaGuardia complains. ‘You give other people away for a living’, Pam tells him sharply.

Video

The film is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, which would seem to be its intended aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. It’s a very clean print, comparable, if not identical, to the print used for Anchor Bay’s DVD release in the US back in 2000. The image is detailed enough, but the many night-time sequences are sometimes difficult to make out owing to weak contrast and crushed blacks. In this respect, it would have been nice to have seen the film released on Blu-ray rather than DVD.

Audio

The Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo track is clean and clear. Music, when it appears (which is frequently), fills the soundscape, offering excellent, rich texture. By contrast, dialogue can sometimes seem to be mixed very low. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Extras on the disc include the film’s original trailer (2:50) and a stills gallery (2:33).

Overall

There are some nice little touches throughout the film, characteristic of Moyle’s other pictures too, such as Nicky and Pam’s reaction when they see a Times Square marquee advertising Carlos Aured’s 1974 film House of Psychotic Women (Los ojos azules de la muneca rota). LaGuardia is a fascinating character: seen depressed and repressed in his job as a DJ (nonchalantly playing back recorded shows as he plays a game of chess with a colleague), he lives vicariously through Pam and Nicky’s adventures. Pam’s escapades with Nicky allow her to experience a new kind of freedom, but to the film’s audience, from the outset, Nicky is clearly reckless and self-destructive – though Nicky says that, ‘They say I’m crazy, but the truth is, I just know bullshit when I see it’. There are some nice little touches throughout the film, characteristic of Moyle’s other pictures too, such as Nicky and Pam’s reaction when they see a Times Square marquee advertising Carlos Aured’s 1974 film House of Psychotic Women (Los ojos azules de la muneca rota). LaGuardia is a fascinating character: seen depressed and repressed in his job as a DJ (nonchalantly playing back recorded shows as he plays a game of chess with a colleague), he lives vicariously through Pam and Nicky’s adventures. Pam’s escapades with Nicky allow her to experience a new kind of freedom, but to the film’s audience, from the outset, Nicky is clearly reckless and self-destructive – though Nicky says that, ‘They say I’m crazy, but the truth is, I just know bullshit when I see it’.

David Laderman has described the film as ‘a sensationalistic effort at packaging teen rebellion for 1980s youth audiences’ which ‘import[s] punk iconography with the apparent design of serving it up for the mainstream, probably with disco’s trajectory in Saturday Night Fever […] in mind’ (2010: 109). Times Square is more interesting than this. The focus on Pam and Nicky is matched by the examination of David’s plan to gentrify Times Square – something which has arguably gained added resonance since Giuliani’s cleaning-up of the area during the 1990s. Curry’s sensitive performance as LaGuardia also gives this character added depth. The tone of the film is uneven, and the structure is choppy, most likely because of Stigwood’s interference in production and post-production, but there’s still much to commend here – though as an example of punk cinema focusing on alienated young women, this is nowhere near as angry or as potent as Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue (released the same year, 1980), for example. The US DVD release from Anchor Bay, now long out of print, included a very interesting commentary featuring input from Moyle and Robin Johnson. It’s a shame this hasn’t been ported over to this release, which also would have benefited from an interview with Moyle or a retrospective featurette. Nevertheless, this disc contains a solid presentation of a film which, despite showing the meddling of its producer, is still a rewarding picture to watch. References: Filippo, Maria San, 2013: The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television. Indiana University Press Fink, Marty, 2011: ‘Fuck/The Police: Queering Narratives of Police Brutality in Post-9/11 New York’. In: Battis, Jes (ed), 2011: Homofiles: Theory, Sexuality, and Graduate Studies. Maryland: Lexington Books: 53-64 Laderman, David, 2010: Punk Slash! Musicals: Tracking Slip-Synch on Film. University of Texas Press This review has been kindly sponsored by:  >

|

|||||

|