|

|

Bird with the Crystal Plumage (The) AKA L'Uccello Dalle Piume Di Cristallo (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st July 2017). |

|

The Film

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (Dario Argento, 1970) The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (Dario Argento, 1970)

Dario Argento’s directorial debut, L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970) established a set of narrative paradigms that Argento would continue to follow in his subsequent naturalistic thrillers – Il gatto a nove code (The Cat O’Nine Tails, 1971) and Quattro mosche di velluto grigio (Four Flies on Grey Velvet, 1971). Subsequently, his thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) films came increasingly to feature fantastical and sometimes supernatural elements, hybridising the thriller and the supernatural horror film – from Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1975) and Suspiria (1977) onwards. In Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980, Danny Shipka suggests that more generally, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage was a watershed film in Italian popular cinema, ‘mark[ing] the beginning of a decade in which the quaintness of previous Italian filmmakers would be replaced by those who gave a gritty, graphic exploration of a society that’s no longer safe’ (Shipka, 2011: 84). In contrast with the thrilling all’italiana films Mario Bava made during the 1960s, which Shipka argues ‘always had an air of quaintness about them’, Argento’s Italian-style thrillers ‘were cool, modern and hip’: Bava’s violence ‘was theatrical and over-the-top’, whereas the violence of Argento’s pictures ‘seemed all too real, rooted in the headlines of the day which made them all the more terrifying’ (ibid.). By paring violence down to ‘the straight kill, nothing but leather and a sharp knife or razor here’, Argento’s pictures emphasised ‘the pure sexual violence that is the root of gialli’ (ibid.). The Bird with the Crystal Plumage opens on Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante), an American writer who, in an attempt to overcome his writer’s block, has taken a job in Rome writing a ‘manual on the preservation of rare birds’ at the advice of his friend Carlo (Renato Romano). Dalmas as taken temporary residence in Rome with his girlfriend, British model Julia (Suzy Kendall).  Walking back to his rented flat after being paid for writing the book, his ties with Italy apparently severed, Dalmas walks past an art gallery. He sees two figures struggling with one another: a woman and a man in a black coat, gloves and hat. The woman is wounded by a large knife. Dalmas approaches the gallery but finds himself trapped between two sets of glass doors. He manages to alert a passer-by, who rushes off to telephone the police; and Dalmas can do nothing but watch the injured woman crawl across the floor towards him. Walking back to his rented flat after being paid for writing the book, his ties with Italy apparently severed, Dalmas walks past an art gallery. He sees two figures struggling with one another: a woman and a man in a black coat, gloves and hat. The woman is wounded by a large knife. Dalmas approaches the gallery but finds himself trapped between two sets of glass doors. He manages to alert a passer-by, who rushes off to telephone the police; and Dalmas can do nothing but watch the injured woman crawl across the floor towards him.

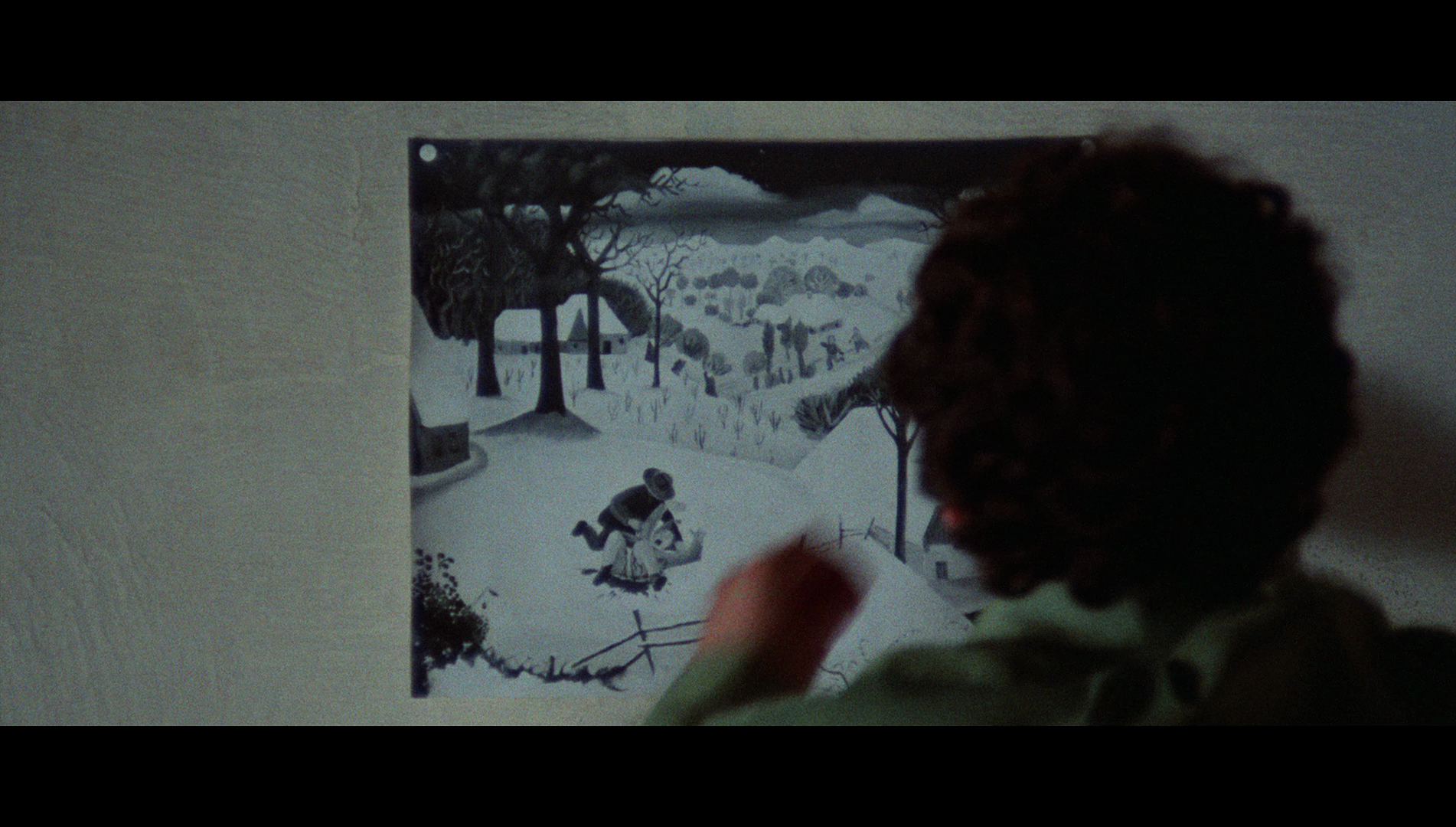

The woman, Monica Ranieri (Eva Renzi), is the wife of the gallery’s owner, Alberto Ranieri (Umberto Raho). She survives; Dalmas is questioned by Inspector Morosini (Enrio Mario Salerno), who takes Dalmas’ passport from him, preventing Dalmas from leaving the country in case he is needed for further questioning. Morosini also reveals to Dalmas that the police believe a serial killer is at work, the bodies of three young women having already been discovered within the city. After leaving the police station, Dalmas is attacked by an assailant wielding a meat cleaver. His resolve tested, Dalmas becomes determined to solve the puzzle: he is convinced he saw something significant at the gallery but can’t pinpoint exactly what it was. Dalmas decides to play amateur sleuth, speaking with the owner of the antiques shop (Werner Peters) in which the killer’s first victim worked. Dalmas discovers that the day of her murder, the girl sold a strange, naïve painting depicting a brutal assault on a woman. Much to Julia’s chagrin, Dalmas returns to the flat with a photographed copy of the painting, convinced that the painting has some connection with the girl’s murder. (‘Looks a bit perverted to me’, Julia observes.) Dalmas next speaks with Garullo (Gildo di Marco), the imprisoned pimp of the second murdered girl, a streetwalker. Later, walking through Rome with Julia, Dalmas tells her of his conversation with Garullo. However, a car runs down their police escort and Dalmas is shot at by a man wearing a yellow jacket. Dalmas is pursued by the man but manages to seek sanctuary in a busy city street. Dalmas’ attacker flees; Dalmas is in pursuit, however, and traces the attacker to a hotel. There, Dalmas is frustrated when he realises that the hotel is hosting a convention for former boxers – and all of them are wearing the same yellow jacket as the man who shot at Dalmas.  Reasoning that the attempts on his life must mean he is getting close to identifying the killer, Dalmas continues with his investigations, returning to converse with Garullo. Garullo points Dalmas to a private investigator, Filagna (Pino Patti), who identifies Dalmas’ attacker as Needles (Reggie Nalder), a drug addict and former prizefighter. Dalmas travels to the address Filagna gives him and discovers Needles’ dead body. Reasoning that the attempts on his life must mean he is getting close to identifying the killer, Dalmas continues with his investigations, returning to converse with Garullo. Garullo points Dalmas to a private investigator, Filagna (Pino Patti), who identifies Dalmas’ attacker as Needles (Reggie Nalder), a drug addict and former prizefighter. Dalmas travels to the address Filagna gives him and discovers Needles’ dead body.

Dalmas receives a threatening phone call from the killer, who speaks in a hoarse whisper, warning Dalmas to ‘Stop playing detective. It isn’t healthy’. Julia manages to record the telephone call using a reel-to-reel tape recorder. A distinctive sound can be heard in the background, something that Carlo later identifies as the cry of a rare bird. Dalmas passes this information on to Morosini, and it seems that Dalmas and the police are on the trail of the killer; but Dalmas leaves Julia at home, alone and vulnerable. The thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana is a remarkably diverse grouping of films, linked by a distinct Italian flavour or style (hence the label thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana – ‘Italian-style thriller’). Consequently, like film noir the thrilling all’italiana can perhaps best be considered a ‘style’ rather than a genre: although the pictures very often (but not always) feature recurring visual elements, in narrative structure and thematic concerns the films are actually incredibly diverse. The thrilling all’italiana encompasses paranoid political thrillers such as La corta notte della bambole di vetro (Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (for example, La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas like Le foto proibite di una signora per bene (The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films). There’s arguably a sense in which the diversity of the thrilling all’italiana has become subsumed amongst English-speaking fans within a focus on the more delirious examples of the genre (which tend to be the ‘woman-in-peril’-type films of directors such as Dario Argento and Sergio Martino), but regardless of this, many of the iconographic elements of the Italian thrilling pictures are often seen as being sourced within Mario Bava’s Sei Donne per l’assassino (Blood & Black Lace, 1964).  Mikel J Koven has suggested that with La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much, 1963) and Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava established many of the tropes of subsequent thrilling all’italiana pictures (Koven, 2006: 3-4). Both films display a very different approach to narrative, but Blood and Black Lace in particular ‘introduced to the genre specific visual tropes that would become cliched’ in subsequent films (ibid.: 4). Chief among these was the level of cruelty and diversity of method within the murders, all committed ‘against beautiful women’ (ibid.). One of the other elements of the more baroque thrilling films that finds its first defining expression in Blood and Black Lace is the depiction of the film’s killer, a mysterious figure clad in black fedora, trenchcoat and leather gloves. (Mikel Koven suggests that the killer’s disguise in Blood and Black Lace may have drawn upon the depiction of the murderer in George Pollock’s Murder She Said, 1961, who also wears a black overcoat and black gloves.) This costume would come to be associated with the more extravagant examples of the thrilling all’italliana via its appearance in a number of Argento’s films, beginning with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and numerous other Italian thrilling films of the 1970s, such as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972) and Paolo Cavara’s La tarantola dal ventre nero (The Black Belly of the Tarantula, 1971), to cite but two examples. Mikel J Koven has suggested that with La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much, 1963) and Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava established many of the tropes of subsequent thrilling all’italiana pictures (Koven, 2006: 3-4). Both films display a very different approach to narrative, but Blood and Black Lace in particular ‘introduced to the genre specific visual tropes that would become cliched’ in subsequent films (ibid.: 4). Chief among these was the level of cruelty and diversity of method within the murders, all committed ‘against beautiful women’ (ibid.). One of the other elements of the more baroque thrilling films that finds its first defining expression in Blood and Black Lace is the depiction of the film’s killer, a mysterious figure clad in black fedora, trenchcoat and leather gloves. (Mikel Koven suggests that the killer’s disguise in Blood and Black Lace may have drawn upon the depiction of the murderer in George Pollock’s Murder She Said, 1961, who also wears a black overcoat and black gloves.) This costume would come to be associated with the more extravagant examples of the thrilling all’italliana via its appearance in a number of Argento’s films, beginning with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and numerous other Italian thrilling films of the 1970s, such as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972) and Paolo Cavara’s La tarantola dal ventre nero (The Black Belly of the Tarantula, 1971), to cite but two examples.

Whilst The Girl Who Knew Too Much wasn’t the first Italian thriller (the label had previously been applied to Luchino Visconti’s 1943 Ossessione, an adaptation of James M Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, for example), Bava’s picture was the film that consolidated the elements of the thrilling all’italiana. (The first Italian detective novel, Il mio cadavere – by Francesco Mastriani, published in 1852 – is sometimes claimed to contain the same fusion of psychological thriller and horror that characterises the later thrilling all’italiana films of directors like Bava and Argento.) Gino Moliterno cites Bava’s film as establishing the narrative template that would define many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana: principally, ‘the story of an innocent eyewitness to a violent murder who takes on the role of amateur detective in order to track down the killer and, in the process, becomes one of the killer’s main targets’ (2009: 151). This basic narrative model would form a core element of the Italian thrillers of the late 1960s and 1970s, and would reappear in films such as Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Deep Red, Luigi Bazzoni’s Giornata nera per l’ariete (The Fifth Cord, 1971), Pupi Avati’s The House with Laughing Windows) and Sergio Martino’s Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh, 1971) and Tutti i colori del buio (All the Colors of the Dark, 1972). Bava’s next entry into the thrilling all’italiana, Blood and Black Lace would establish both one of the Italian thriller’s most lasting visual paradigms (a killer clad in a black trenchcoat and fedora, and wearing black leather gloves), as well as the emphasis on setpieces which depict murder as a form of Sadean spectacle that would come to the fore in Argento’s gialli (and would also work its way into American bodycount/stalk-and-slash/slasher films during the late-1970s and 1980s).  The Bird with the Crystal Plumage foregrounds the importance of the setpiece for Argento’s cinema, with its opening sequence which sees Sam Dalmas trapped in the glass doors of the Ranieris’ gallery, unable to assist Monica and forced to watch the violence unfold. Via a use of high-angle shots of Monica to suggest her powerlessness and victimhood, point-of-view shots from Sam’s perspective and low-angle close-ups of Dalmas which reinforce the frustration on his face (acted, it has to be said, brilliantly by Musante), Argento consolidates Dalmas’ interpretation of events. The clean, brightly lit interior of the gallery – dominated by white walls and floors, and decorated with bizarre objets d’art – is contrasted with the dark, dingy night-time streets outside. Trapped in the glass doors, Dalmas becomes a spectator to the violence that takes place inside, his position liminal – between the worlds of art and the street. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage foregrounds the importance of the setpiece for Argento’s cinema, with its opening sequence which sees Sam Dalmas trapped in the glass doors of the Ranieris’ gallery, unable to assist Monica and forced to watch the violence unfold. Via a use of high-angle shots of Monica to suggest her powerlessness and victimhood, point-of-view shots from Sam’s perspective and low-angle close-ups of Dalmas which reinforce the frustration on his face (acted, it has to be said, brilliantly by Musante), Argento consolidates Dalmas’ interpretation of events. The clean, brightly lit interior of the gallery – dominated by white walls and floors, and decorated with bizarre objets d’art – is contrasted with the dark, dingy night-time streets outside. Trapped in the glass doors, Dalmas becomes a spectator to the violence that takes place inside, his position liminal – between the worlds of art and the street.

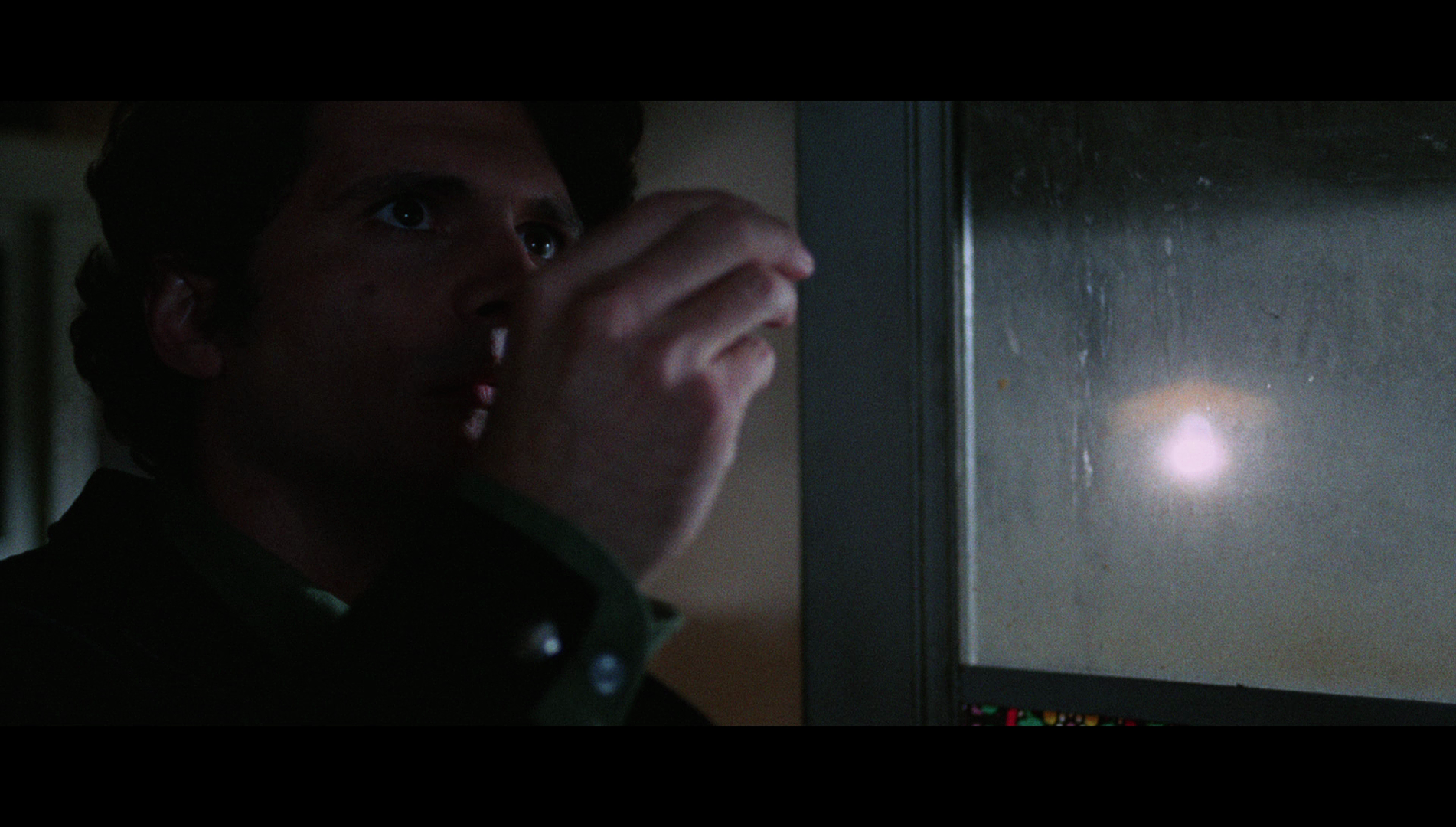

Ellen Nerenberg suggests that Argento’s films are driven by the key themes of ‘[s]eeing and decoding clues, the work of detection (not to mention of semiotics and cinema studies)’ (2012: 82). Argento’s pictures often embed ‘clues in an obviously “artistic” structure that serves to frame knowledge, detection and, resolution’ (ibid.: 83). Dalmas’ witnessing of the attack in the gallery imprints itself on his psyche, to the extent that Dalmas is unable to progress with his life until he has solved the riddle of what he witnessed, returning again and again to his memories of the scene in the gallery (even whilst his girlfriend Julia is attempting to seduce him) and trying to interpret the visual evidence presented to him. The visual sense of entrapment represented in the image of Dalmas trapped within the glass doors of the gallery becomes a metaphor for the stasis of Dalmas’ life – his entrapment within the mystery. The narrative returns to this scene obsessively as Dalmas seeks to decode it, obsessed with the idea that the clues to the crime (and the murders that have been plaguing Rome) lie in successfully interpreting what he saw that night. ‘There was something wrong with that scene’, Dalmas tells Morosini during his interview by the police, ‘Something odd. I can’t pin it down but I have a definite feeling that something didn’t fit’. For Nerenberg, this particular ‘scene signifies misunderstanding and frustration, of seeing something but not believing it, and, importantly, seeing something but not trusting yourself to testify about it. Above all, the scene is about the difficulty of expressing what you believe you have witnessed’ (ibid.). ‘I have a feeling that I’m closer to the truth than even one of us realises’, Dalmas tells Julia later, before adding: ‘What’s happening to me? This damn thing is turning into an obsession!’ Similar scenes recur throughout Argento’s examples of the thrilling subgenre: in Deep Red, Marc Daly’s witnessing of the death of a psychic (Macha Meril) is coloured by his belief that he has seen the murderer; in Cat O’Nine Tails, Franco Arno (Karl Malden) witnesses a murder, but he is blind and thus only has part of the puzzle.  Much writing about The Bird with the Crystal Plumage has focused on how in this scene, Dalmas’ position is roughly analogous to that of the film’s audience, the glass doors acting like the cinema screen – impenetrable/impassable but offering a window onto a world in which sadistic violence is often enacted for our voyeuristic enjoyment. In this sense, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage invites comparisons with Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), an adaptation of Cornell Woolrich’s short story ‘It Had to Be Murder’ (1942); in Rear Window, of course, injured photographer Jefferies (James Stewart) witnesses what he believes to be a murder through the rear window of his Greenwich Village apartment. Unable to intervene directly, and frustrated by the police’s seeming disinterest in investigating the alleged crime, Jefferies enlists the help of his fiancée (Grace Kelly) to reach beyond the window and find out the truth. Similarly, in Ted Tetzlaff’s 1949 film noir The Window, a young boy, Tommy (Bobby Driscoll), witnesses a murder whilst looking in through the window of his neighbour’s apartment. Tommy tries to get the authorities to believe his story, but they refuse to; and the violence that he has witnessed within his neighbours’ apartment threatens to intrude into Tommy’s world. Much writing about The Bird with the Crystal Plumage has focused on how in this scene, Dalmas’ position is roughly analogous to that of the film’s audience, the glass doors acting like the cinema screen – impenetrable/impassable but offering a window onto a world in which sadistic violence is often enacted for our voyeuristic enjoyment. In this sense, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage invites comparisons with Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), an adaptation of Cornell Woolrich’s short story ‘It Had to Be Murder’ (1942); in Rear Window, of course, injured photographer Jefferies (James Stewart) witnesses what he believes to be a murder through the rear window of his Greenwich Village apartment. Unable to intervene directly, and frustrated by the police’s seeming disinterest in investigating the alleged crime, Jefferies enlists the help of his fiancée (Grace Kelly) to reach beyond the window and find out the truth. Similarly, in Ted Tetzlaff’s 1949 film noir The Window, a young boy, Tommy (Bobby Driscoll), witnesses a murder whilst looking in through the window of his neighbour’s apartment. Tommy tries to get the authorities to believe his story, but they refuse to; and the violence that he has witnessed within his neighbours’ apartment threatens to intrude into Tommy’s world.

Like the narratives of these films, the predicament in which Dalmas finds himself within The Bird with the Crystal Plumage could be, and often has been, taken as a metaphor for the cinema-going experience itself; Argento’s first film is therefore boldly metafictional, something which characterises many of the director’s later pictures (for example, 1987’s Opera, in which a young opera singer, Betty, is forced by a serial killer to watch the murders he commits). For the film critic-turned-writer/director, however, the pivotal scene perhaps has another level of resonance: a frustrated novelist, who has taken freelance employment in Italy as a ‘jobbing’ technical writer, the trapped Dalmas gazes in from the cold, unable to reach the world of privilege and art which is represented by the interior of the gallery. (‘Sam Dalmas, great hope of American literature, now writing manuals on the preservation of rare birds’, Dalmas jokes to Carlo in the film’s opening sequence.) The film’s early dialogue between Sam and Carlo highlights the extent to which Dalmas resents the work he has been forced by circumstance to take, seeing his employ as a jobbing technical writer as a pollution of his ‘dream’. ‘Don’t you want a copy of the book?’, Carlo asks Sam after Sam has collected his cheque for writing it. ‘Who needs it?’, Dalmas asks, holding the cheque aloft, ‘I have this’. The distinction between Dalmas’ dreams of being the ‘great hope of American literature’ and his acceptance of a ‘job of work’ writing a technical book is perhaps intentionally analogous to the distinction, for a young film director such as Argento was at the time he made this picture, between being an auteur and a ‘jobbing’ director.  Like many examples of the thrilling all’italiana, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage focuses on a theme of transnationality by emphasising the ‘otherness’ of its protagonist: within the film’s opening moments, Dalmas is foregrounded as a cultural outsider, an American author ‘slumming it’ in Italy. Needham has suggested that the opening sequence of Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, in which the American protagonist arrives in Italy via plane, establishes a number of tropes of later examples of the Italian thriller: ‘the foreigner coming to/being in Italy; the obsession with travel and tourism not only as a mark of the newly emerging European jet set (consider how many gialli begin or end in airports), but representative of Italian cinema’s selling of its own “Italian-ness” through tourist hotspots… and of course fashion and style’ (quoted in Mendik, 2014: 391; ellipsis in original). As Xavier Mendik has observed, key to solving the crime in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is Dalmas’ journey to yet another landscape: rural Italy (ibid.: 393). There, Dalmas questions the artist who painted the picture that is at the heart of the mystery, the eccentric cat-eating Berto Consalvi (Mario Adorf). Where the city is a place of danger, it is at least policed; but the Italian countryside is depicted as threatening in its openness and isolation. ‘If you take my advice, you’ll get out of here’, the taxi driver who takes Dalmas to Consalvi’s isolated rural home asserts, ‘The man [Consalvi] is crazy’. Dalmas is weary when approaching Consalvi’s home, which he must enter via a ladder leading to an upstairs window. (‘Why did you wall up the house?’, Dalmas asks Consalvi. ‘To keep out the busybodies’, Consalvi responds, ‘Besides, there’s cats’.) Given the brutality of the scene depicted within the painting, the potential for violence hangs over Dalmas’ questioning of Consalvi; meanwhile, Consalvi himself embodies negative rural stereotypes – of strange, insular and culturally backward communities – familiar from other examples of the thrilling all’italiana and, more widely, a range of international films of the 1970s (John Boorman’s Deliverance, 1972; Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, 1972). Consalvi spends his time constructing naïve art of childlike simplicity, but doing so with utter seriousness: he is a mixture of the aspirational and the backward, his ‘serious’ approach to his art in many ways mirroring Dalmas’ attitudes towards writing. Dalmas asks Consalvi about the painting that the girl who worked in the antique shop sold, presumably to the killer; Consalvi responds, ‘I don’t do that crap anymore. I’m going through a mystical period. I only paint mystical scenes’. ‘Why?’, a puzzled Dalmas asks. ‘Because I’m feeling mystical’, Consalvi answers. Like many examples of the thrilling all’italiana, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage focuses on a theme of transnationality by emphasising the ‘otherness’ of its protagonist: within the film’s opening moments, Dalmas is foregrounded as a cultural outsider, an American author ‘slumming it’ in Italy. Needham has suggested that the opening sequence of Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, in which the American protagonist arrives in Italy via plane, establishes a number of tropes of later examples of the Italian thriller: ‘the foreigner coming to/being in Italy; the obsession with travel and tourism not only as a mark of the newly emerging European jet set (consider how many gialli begin or end in airports), but representative of Italian cinema’s selling of its own “Italian-ness” through tourist hotspots… and of course fashion and style’ (quoted in Mendik, 2014: 391; ellipsis in original). As Xavier Mendik has observed, key to solving the crime in The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is Dalmas’ journey to yet another landscape: rural Italy (ibid.: 393). There, Dalmas questions the artist who painted the picture that is at the heart of the mystery, the eccentric cat-eating Berto Consalvi (Mario Adorf). Where the city is a place of danger, it is at least policed; but the Italian countryside is depicted as threatening in its openness and isolation. ‘If you take my advice, you’ll get out of here’, the taxi driver who takes Dalmas to Consalvi’s isolated rural home asserts, ‘The man [Consalvi] is crazy’. Dalmas is weary when approaching Consalvi’s home, which he must enter via a ladder leading to an upstairs window. (‘Why did you wall up the house?’, Dalmas asks Consalvi. ‘To keep out the busybodies’, Consalvi responds, ‘Besides, there’s cats’.) Given the brutality of the scene depicted within the painting, the potential for violence hangs over Dalmas’ questioning of Consalvi; meanwhile, Consalvi himself embodies negative rural stereotypes – of strange, insular and culturally backward communities – familiar from other examples of the thrilling all’italiana and, more widely, a range of international films of the 1970s (John Boorman’s Deliverance, 1972; Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, 1972). Consalvi spends his time constructing naïve art of childlike simplicity, but doing so with utter seriousness: he is a mixture of the aspirational and the backward, his ‘serious’ approach to his art in many ways mirroring Dalmas’ attitudes towards writing. Dalmas asks Consalvi about the painting that the girl who worked in the antique shop sold, presumably to the killer; Consalvi responds, ‘I don’t do that crap anymore. I’m going through a mystical period. I only paint mystical scenes’. ‘Why?’, a puzzled Dalmas asks. ‘Because I’m feeling mystical’, Consalvi answers.

Consalvi’s insistence on his ‘mystical period’ is in stark contrast with the police force’s application of technology and science to identify the killer. The police use a high tech computer which, when inputted with a description of the killer, prints out the names of all residents of Rome matching that description (which number the hundreds of thousands); they also employ voice analysis and recording technology. Through analysis of a glove, they manage to determine (incorrectly) the fact that the killer is left-handed and smokes expensive cigars. (The latter plot development may perhaps be an allusion to Sherlock Holmes’ monograph ‘Upon the Distinction Between the Ashes of Various Tobaccos’, which forms a key plot point in a number of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories.) However, even with all of this technology at their disposal, they fail to correctly identify the killer: the eventual apprehension of the killer is down to Dalmas’ dogged insistence on investigating the crime and solving the puzzle within his perception of the assault in the gallery. The technology and rigid methods employed by the police lead them down a proverbial blind alley, in search of the wrong suspect. (Meanwhile, the killer uses technology – 35mm photography – to identify and monitor their victims.) The illogicality of the killer’s motivation is underscored in the film’s closing sequence. Morosini appears on a television programme, discussing the capture of the killer, and he invites a psychiatrist to explain the killer’s motivation. A case of ‘too little, too late’, the psychiatrist’s explanation is as convoluted and unconvincing as that given by the psychiatrist (Simon Oakland) at the end of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) to explain Norman Bates’ behaviour. Hitchcock’s film satirises the belief that incoherent violence can be explained by rational discourse; it’s unclear whether the closing sequence of Argento’s film was intended to be similarly satirical, or whether it was simply a pastiche of the closing sequence of Psycho – one of a dense web of allusions that Argento makes within his picture. Either way, the effect remains the same: the audience is left with a sense that the attempts to explain the violence of the killer via the application of a rational, scientific method are unconvincing; that the self is unknowable, as are human motivations for behaviour, and that violence is a disruptive, irrational force. Consalvi’s insistence on his ‘mystical period’ is in stark contrast with the police force’s application of technology and science to identify the killer. The police use a high tech computer which, when inputted with a description of the killer, prints out the names of all residents of Rome matching that description (which number the hundreds of thousands); they also employ voice analysis and recording technology. Through analysis of a glove, they manage to determine (incorrectly) the fact that the killer is left-handed and smokes expensive cigars. (The latter plot development may perhaps be an allusion to Sherlock Holmes’ monograph ‘Upon the Distinction Between the Ashes of Various Tobaccos’, which forms a key plot point in a number of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories.) However, even with all of this technology at their disposal, they fail to correctly identify the killer: the eventual apprehension of the killer is down to Dalmas’ dogged insistence on investigating the crime and solving the puzzle within his perception of the assault in the gallery. The technology and rigid methods employed by the police lead them down a proverbial blind alley, in search of the wrong suspect. (Meanwhile, the killer uses technology – 35mm photography – to identify and monitor their victims.) The illogicality of the killer’s motivation is underscored in the film’s closing sequence. Morosini appears on a television programme, discussing the capture of the killer, and he invites a psychiatrist to explain the killer’s motivation. A case of ‘too little, too late’, the psychiatrist’s explanation is as convoluted and unconvincing as that given by the psychiatrist (Simon Oakland) at the end of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) to explain Norman Bates’ behaviour. Hitchcock’s film satirises the belief that incoherent violence can be explained by rational discourse; it’s unclear whether the closing sequence of Argento’s film was intended to be similarly satirical, or whether it was simply a pastiche of the closing sequence of Psycho – one of a dense web of allusions that Argento makes within his picture. Either way, the effect remains the same: the audience is left with a sense that the attempts to explain the violence of the killer via the application of a rational, scientific method are unconvincing; that the self is unknowable, as are human motivations for behaviour, and that violence is a disruptive, irrational force.

Many of Argento’s films confront issues of gender and sexuality, containing characters who challenge the heterosexual norm. From the openly gay private detective played by Jean-Pierre Marielle in Four Flies on Grey Velvet and the unusual chromosomal makeup of the killer in Cat O’Nine Tails, to the use of transgendered actor Eva Robins in Tenebre (Tenebrae, 1982) and the examination of the fluidity of gendered identity in La sindrome di Stendahl (The Stendahl Syndrome, 1996), Argento’s films focus on gender – and especially, the performative aspects of gender identity – in often explicit ways. Both The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Four Flies on Grey Velvet, for example, feature antagonists who are motivated by their cross-gendered identification: in the case of the former film, the killer is a woman who murders allegedly because of her cross-gendered identification with the man who attacked her; and in the case of the latter, the killer is a woman whose parents raised her as a boy. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage returns again and again to the question of sexuality – most obviously in the sexual nature of the violence (the killer strips off the underwear of one of the victims before thrusting a knife between her legs in a grotesque parody of the sexual act), but also in the lineup of ‘perverts’ that Morosini gathers for Dalmas. The Italian version lists some of the ‘perversions’ of the men gathered in the lineup, identifying some of them as practising ‘sodomites’ (the English version shies away from this); later, the exaggeratedly camp owner of the antiques shop in which the first victim worked flirts with Dalmas before declaring, secretively, that the murdered girl was a lesbian. ‘I couldn’t care less’, the shop owner asserts, ‘I’m no racist, for heaven’s sake’. In these scenes, Argento seems to be satirising attitudes towards homosexuality. Also during the scene in which the lineup takes place, the script foreshadows the climax’s focus on the killer’s cross-gendered identification and her cross-dressing during the murders: a transvestite (nicknamed ‘Ursula Andress’) is included in the lineup, but Morosini protests ‘How many times do I have to tell you? “Ursula Andress” belongs with the transvestites, not the perverts’. (Ironically, of course, the killer Morosini is seeking is indeed a cross-dresser.) Many of Argento’s films confront issues of gender and sexuality, containing characters who challenge the heterosexual norm. From the openly gay private detective played by Jean-Pierre Marielle in Four Flies on Grey Velvet and the unusual chromosomal makeup of the killer in Cat O’Nine Tails, to the use of transgendered actor Eva Robins in Tenebre (Tenebrae, 1982) and the examination of the fluidity of gendered identity in La sindrome di Stendahl (The Stendahl Syndrome, 1996), Argento’s films focus on gender – and especially, the performative aspects of gender identity – in often explicit ways. Both The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Four Flies on Grey Velvet, for example, feature antagonists who are motivated by their cross-gendered identification: in the case of the former film, the killer is a woman who murders allegedly because of her cross-gendered identification with the man who attacked her; and in the case of the latter, the killer is a woman whose parents raised her as a boy. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage returns again and again to the question of sexuality – most obviously in the sexual nature of the violence (the killer strips off the underwear of one of the victims before thrusting a knife between her legs in a grotesque parody of the sexual act), but also in the lineup of ‘perverts’ that Morosini gathers for Dalmas. The Italian version lists some of the ‘perversions’ of the men gathered in the lineup, identifying some of them as practising ‘sodomites’ (the English version shies away from this); later, the exaggeratedly camp owner of the antiques shop in which the first victim worked flirts with Dalmas before declaring, secretively, that the murdered girl was a lesbian. ‘I couldn’t care less’, the shop owner asserts, ‘I’m no racist, for heaven’s sake’. In these scenes, Argento seems to be satirising attitudes towards homosexuality. Also during the scene in which the lineup takes place, the script foreshadows the climax’s focus on the killer’s cross-gendered identification and her cross-dressing during the murders: a transvestite (nicknamed ‘Ursula Andress’) is included in the lineup, but Morosini protests ‘How many times do I have to tell you? “Ursula Andress” belongs with the transvestites, not the perverts’. (Ironically, of course, the killer Morosini is seeking is indeed a cross-dresser.)

Through its mixture of British, American and European actors, it’s clear that The Bird with the Crystal Plumage was made with a keen eye on the export market. The popularity of the film for Italian audiences, sparking a trend in gialli all’italiana that exploited and explored labyrinthine urban environments in which killers stalked their victims from the shadows, was perhaps owing to the increasing perception within Italy, following the Piazza Fontana bombing of 1969 and numerous similar events, of the urban space as dangerous. Andrea Bini suggests that ‘Argento’s great insight was to show how undefined fear and irrational violence had become two crucial elements of Italian daily life [….] Argento’s films portray the fears of Italians whose cities and communities had undergone such rapid growth and change that they had become unfamiliar and threatening places’ (Bini, 2011: 65). The irrationality of the violence depicted within the films suggests ‘that anyone can become a victim at any time’ (ibid.). The dialogue openly parodies perceptions of Italy as a peaceful country: ‘“Go to Italy”, he said’, Dalmas asserts sarcastically in reference to the advice he was given to spend time in Italy as a means of overcoming his writer’s block, ‘“You need peace and tranquillity [….] Nothing ever happens in Italy”. May he rot in hell!’

Video

The film takes up a little over 26Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Presented uncut, with a running time of 96:44 mins, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film takes up a little over 26Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Presented uncut, with a running time of 96:44 mins, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage was shot in Cromoscope, a 2-perf widescreen process that was identical to Techniscope, other than it was handled by a different laboratory. Both Techniscope and Cromoscope were widescreen processes that used spherical, rather than anamorphic, lenses. They were cost-saving in the sense that, by halving the size of each frame in comparison with anamorphic (4-perf) widescreen processes, they reduced the negative costs involved in making a film by half. However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by lab costs, which it is said were more expensive for films shot in 2-perf formats like Techniscope/Cromoscope; it has also been suggested that increases in lab costs were one of the reasons why 2-perf non-anamorphic widescreen processes such as these became less popular during the late 1970s and the 1980s. Release prints of Techniscope/Cromoscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense/coarse than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s even more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)  The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is a beautifully photographed film, Vittorio Storaro making full use of the Cromoscope frame. (Anyone who saw the film’s cropped VHS releases can attest to how badly the film’s composions have in the past been damaged by the cropping.) For this release, he film has been restored in 4k from the original negative. The use of the negative as the source material for this presentation thus bypasses the 4-perf ‘blow up’ process, and as a result, blacks are deep and velvety, in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of the film is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the vintage prints of Techniscope films made after around 1970. The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is a beautifully photographed film, Vittorio Storaro making full use of the Cromoscope frame. (Anyone who saw the film’s cropped VHS releases can attest to how badly the film’s composions have in the past been damaged by the cropping.) For this release, he film has been restored in 4k from the original negative. The use of the negative as the source material for this presentation thus bypasses the 4-perf ‘blow up’ process, and as a result, blacks are deep and velvety, in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of the film is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the vintage prints of Techniscope films made after around 1970.

Contrast levels are very good: midtones have strong definition, and highlights are even. Blacks are deep, as noted above, and rich in texture. An extremely rich level of fine detail is present, accounting for the fact that the film was shot in a 2-perf format. Colour is robust. In comparison with Blue Underground’s Blu-ray release from a few years ago (see at the bottom of this review for some comparison grabs between Arrow’s new Blu-ray and Blue Underground’s older release), this new presentation has bolder, more saturated reds, resulting in skintones that seem less ‘washed out’. Also in comparison with Blue Underground’s Blu-ray release, the framing in Arrow’s new presentation has been opened up a little on all four sides. There’s no distracting damage, and no evidence of harmful digital tinkering. Surprisingly, given the violence in the picture, the film was released in the US with a ‘PG’ classification, with some cuts made to two of the murder scenes: (i) a shot in which the killer rips the underwear from one of the victims; and (ii) brief cuts to the shot of the killer slashing another victim’s face with a straight razor. In the UK, the picture was released under the title The Gallery Murders in 1970; this version was identical to the US release, without further cuts imposed by the BBFC. In 1983, the same edit of the film was released on VHS by Vampix, prior to the Video Recordings Act. For the film’s release on VHS by Stablecane in 1985 (post-VRA, with an ‘18’ classification), the film was cut further by the BBFC, who demanded the removal of almost 25 seconds from the scene in which the killer removes the underwear of one of his victims, and another second and a half from the murder in the elevator. (These VHS releases were panned-and-scanned, the compositions compromised heavily by this process.) The cuts persisted into the 2005 DVD release from Platinum. Arrow’s 2012 Blu-ray release was uncut, for the first time in the UK, but the compositions were badly compromised by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s demand that the film be released in a 2.00:1 ratio, his favoured screen ratio since 1988. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release therefore represents the first time the film has been released on home video in the UK both uncut and in the film’s original aspect ratio! NB. Please see the bottom of this review for some large screengrabs from Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation of the film and a visual comparison with Blue Underground’s older Blu-ray release.

Audio

The disc presents the viewer with two audio options: an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 track, with optional English HoH subtitles; and an Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 track with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. If the latter audio option is selected, the film plays with the onscreen text inserts in Italian (with optional English subs); if the former track is played, these text inserts are in English. Both tracks are audible and have good range, though the English track is a little clearer and more crisp; the Italian track, by comparison, is very slightly muffled. The disc presents the viewer with two audio options: an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 track, with optional English HoH subtitles; and an Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 track with optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue. If the latter audio option is selected, the film plays with the onscreen text inserts in Italian (with optional English subs); if the former track is played, these text inserts are in English. Both tracks are audible and have good range, though the English track is a little clearer and more crisp; the Italian track, by comparison, is very slightly muffled.

Attentive viewers will be pleased to note that the word ‘Right’ in Morosini’s line ‘Right, bring in the perverts’ is present; this was missing from Blue Underground’s US Blu-ray release of the film. There are some notable differences between the dialogue in the English version and that in the Italian version. In the English version, the examination of the glove found in the gallery is said to reveal particles of a ‘particular type of fabric made only in England’; in the Italian version, this is revealed to be cashmere wool. When Morosini has the ‘perverts’ presented for Dalmas in a lineup, the Italian version identifies their ‘perversions’ whereas the English version elides this. In the Italian version, Monica Ranieri is said to live in a flat on the fifth floor of the building; in the English version, the flat is said to be on the third floor. In some scenes, the differences between the English and Italian dialogue are stark. Following the attempt on his life by Needles (Reggie Nalder), in the English version Dalmas tells Morosini ‘I didn’t see his [the attacker’s] face clearly’. However, in the Italian version Dalmas asserts instead ‘It’s impossible to forget a face like that’. Perhaps most significantly, after listening to the reel-to-reel recording of the killer’s threatening telephone call to Dalmas, in the English version Carlo identifies the bird as having ‘long white feathers that look like glass’. However, in the Italian version Carlo’s response explains the film’s title: the bird, Carlo says, has ‘silver plumage that looks like crystal’. The Italian version thus makes the relevance of the film’s title much more clear.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- A new audio commentary by Troy Howarth. Howarth delivers an enthusiastic commentary for the picture. He begins by talking about Argento’s use of Morricone’s music as a counterpoint to the violence, and the significance in the opening titles sequence of the fetishistic imagery of the knives and gloved hands of the killer. He talks about the film’s importance within Argento’s body of work, and reflects on some of the casting decisions – and what the actors bring to their respective roles. Howarth’s first viewing of the film echoes that of myself, and probably the majority of Argento fans of a similar age: a panned-and-scanned VHS release. Howarth reflects on how much of the film’s impact was diminished within the film’s early home video releases, but considers how even despite this mangling of the film’s aesthetic, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage managed to find a strong cult following. - ‘Black Gloves and Screaming Mimis’ (31:54). Kat Ellinger, the co-editor of Diabolique Magazine, discusses The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and its relationships with other gialli all’italiana of the era. Ellinger also talks about Fredric Brown’s novel The Screaming Mimi, often cited as an inspiration for Argento’s directorial debut. - ‘The Power of Perception’ (20:56). Australian film critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas narrates a video essay that focuses on the significance within Argento’s cinema of works of art – which, in Argento’s films, are often framed as clues and as symbols of past traumas. Heller-Nicholas connects this with the theory of the gaze, derived from Laura Mulvey’s work. - ‘Crystal Nightmare’ (31:24). Dario Argento is featured in a new interview, in which he reflects on the genesis of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage during a holiday in Tunisia and inspired by a reading of Fredric Brown’s The Screaming Mimi. Argento talks about how he came to direct the film – something which he hadn’t initially planned to do. The process of writing the picture, Argento suggests, was organic and spontaneous, and he discusses the writing of the picture in almost mystical terms: ‘I heard voices in my home. I felt like there were ghosts around or people suffering’, he says. Argento reflects on the production of the picture and its distribution by Titanus. He talks in detail about the casting and photography, and he talks about the tense relationship he had with Musante on the set of the picture. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘An Argento Icon’ (22:05). In another new interview, actor Gildo Di Marco – who plays the pimp Garullo in the picture – reflects on the beginnings of his acting career thanks to a photo essay, in which Di Marco appeared, that was featured in Life magazine. He discusses his first meeting with Argento which convinced Di Marco the young director was ‘extraordinary’, and he suggests Argento’s approach to directing actors was easygoing. DI Marco also talks about the impact of the film on Argento’s career. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Eva’s Talking’ (11:18). In an interview recorded the year of her death in 2005, Eva Renzi discusses her role in the film, commenting on how she came to be involved in the picture. She discusses some of her other screen roles of the period too. Renzi speaks in English. - Trailers: Italian trailer (3:11); International trailer (2:48); 2017 Texas Frightmare tailer (0:55).

Overall

An important film in the development of the thriller, not just the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage consolidated the template for many Italian thrillers to come during the 1970s – as well as the films of those directors inspired by examples of the thrilling all’italiana, such as Brian De Palma (who cribbed the staging of the elevator murder scene in Dressed to Kill from Argento’s directorial debut). The Bird with the Crystal Plumage also established the paradigms for Argento’s subsequent films, though throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s Argento increasingly privileged fantastical or supernatural elements. It’s hard, and perhaps even impossible, to find an objective standpoint vis-à-vis Argento’s films: they are a love-or-hate proposition at the best of times. I spent much of the early part of the 21st Century teaching Film Studies alongside a colleague who despised Argento’s films whilst I was – and remain – an avowed fan, though with some qualifications. My friend / colleague and I had long discussions of the relative merits of Argento’s pictures, and though I can acknowledge his criticisms that Argento’s films are often overdirected, hysterical and dominated by the logic and demands of the setpiece, for me Argento’s best films weave a spell which is inspirational. (As an undergraduate student of literature during the 1990s, repeated viewings of Argento’s early 1970s thrillers inspired me to write an unpublished – and, to be fair, probably unpublishable – novel.) Amongst fans of Argento’s work, there sometimes seems to be a division between those who prefer his naturalistic thrillers and those who privilege the films that foreground supernatural elements (such as Suspira and Inferno, 1980). I tend to fall into the former camp, and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is, for me, one of Argento’s best films – alongside Tenebre (1982) and Opera. An important film in the development of the thriller, not just the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage consolidated the template for many Italian thrillers to come during the 1970s – as well as the films of those directors inspired by examples of the thrilling all’italiana, such as Brian De Palma (who cribbed the staging of the elevator murder scene in Dressed to Kill from Argento’s directorial debut). The Bird with the Crystal Plumage also established the paradigms for Argento’s subsequent films, though throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s Argento increasingly privileged fantastical or supernatural elements. It’s hard, and perhaps even impossible, to find an objective standpoint vis-à-vis Argento’s films: they are a love-or-hate proposition at the best of times. I spent much of the early part of the 21st Century teaching Film Studies alongside a colleague who despised Argento’s films whilst I was – and remain – an avowed fan, though with some qualifications. My friend / colleague and I had long discussions of the relative merits of Argento’s pictures, and though I can acknowledge his criticisms that Argento’s films are often overdirected, hysterical and dominated by the logic and demands of the setpiece, for me Argento’s best films weave a spell which is inspirational. (As an undergraduate student of literature during the 1990s, repeated viewings of Argento’s early 1970s thrillers inspired me to write an unpublished – and, to be fair, probably unpublishable – novel.) Amongst fans of Argento’s work, there sometimes seems to be a division between those who prefer his naturalistic thrillers and those who privilege the films that foreground supernatural elements (such as Suspira and Inferno, 1980). I tend to fall into the former camp, and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is, for me, one of Argento’s best films – alongside Tenebre (1982) and Opera.

Aside from some curious elements of mise-en-scène within Dalmas’ flat (a poster of Einstein above Dalmas’ head; a Black Power poster next to the door), The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is visually impactful, owing to Tovoli’s superb photography. This, combined with Morricone’s atonal, experimental score, gives the film a distinctive flavour that many films after have tried to emulate. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is more robust than previous home video incarnations of The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and the film itself is accompanied by some very good exclusive contextual material. The new interview with Argento, in particular, is illuminating. This release comes with a very strong recommendation. References: Bini, Andrea, 2011: ‘Horror Cinema: The Emancipation of Women and Urban Anxiety’. In: Brizio-Skov, Flavia (ed), 2011: Popular Italian Cinema: Culture and Politics in a Postwar Society. London: I B Tauris: 53-82 Bondanella, Peter, 2009: A History of Italian Cinema. London: Continuum International Publishing Cooper, L Andrew, 2012: Contemporary Film Directors: Dario Argento. University of Illinois Press Gracey, James, 2010: Dario Argento. London: Kamera Books Hutchings, Peter, 2009: The A to Z of Horror Cinema. Scarecrow Press Jones, Alan, 1996: Mondo Argento. Upton, Cambridgeshire: Midnight Media Koven, Mikel J, 2005: ‘Space and Place in Italian Giallo Cinema: The Ambivalence of Modernity’. In: Everett, Wendy & Goodbody, Axel (eds), 2005: Revisiting Space: Space and Place in European Cinema. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG: 115-33 Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press McDonagh, Maitland, 1991: Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento. London: Sun Tavern Fields Mendik, Xavier, 2014: ‘The Return of the Rural Repressed: Italian Horror and the Mezzogiorno Giallo’. In: Benshoff, Harry M (ed), 2014: A Companion to the Horror Film. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons: 390-405 Moliterno, Gino, 2008: Historical Dictionary of Italian Cinema. Scarecrow Press Moliterno, Gino, 2009: The A to Z of Italian Cinema. Scarecrow Press Nerenberg, Ellen, 2012: Murder Made in Italy: Homicide, Media, and Contemporary Italian Culture. Indiana University Press Olney, Ian, 2013: Euro Horror: Classic European Cinema in Contemporary American Culture. Indiana University Press Paul, Louis, 2004: Italian Horror Film Directors. London: McFarland Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Screen grab comparison with Blue Underground’s Blu-ray release. Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

Blue Underground:

Arrow (new):

More grabs from the new Arrow disc:

|

|||||

|