|

|

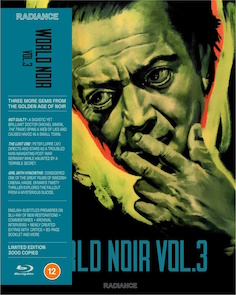

World Noir Vol. 3: Not Guilty/The Lost One/Girl with Hyacinths - Limited Edition

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Radiance Films Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (15th September 2025). |

|

The Film

"The conclusion of World War Two saw film noir become firmly established as one of the defining Hollywood film genres, with studios almost unable to keep up with audience demand for more violent and bleak stories of murder, greed and betrayal. But outside of the USA, a number of European film-makers, many of whom were still reeling from the destruction levied by years of war on their respective countries, were creating works that were every bit the equal of their contemporaneous American counterparts, while often applying uniquely European sensibilities to the recently established noir framework. This set features three such classic examples of European noir from the post-war period, with all three presented on Blu-ray with English subtitles for the very first time." Not Guilty: Looked down upon and socially-ostracized by his professional contemporaries, Doctor Michel Ancelin (Blanche's Michel Simon) spends most of his days making house calls to poorer residents in the surrounding farmland and his nights in a drunken stupor. Ancelin's girlfriend Madeleine (The Lower Depths' Jany Holt) – equally held in low regard for living with him as an unmarried woman and backhandedly described as a "Samaritan" for her choice in partner – tracks him down one night to take him home and Michel takes the wheel drunk, striking a motorcyclist on a dark road. Madeleine watches as suddenly-clearheaded Ancelin arranges the scene to look like an accident, removing the bulb from the bike's lamp and smearing the car's tire tracks. The next day, Ancelin goes into town and solicits news on the motorcyclist, learning from local paper editor Aubignac (The Quiet American's Georges Bréhat) that the rider had stolen the bike and the crash had been ruled as an accident which he further editorializes as "God's justice." Ancelin is satisfied with himself and Madeleine's seeming admiration of him even as he presses the local gendarme Louvet (Elevator to the Gallows' François Joux) on the possibility of foul play; that is, until he realizes that Madeleine has been cheating on him with the town's Lothario mechanic Meilleux. When the mechanic is found murdered in his shop, Ancelin once again plays the interested observer and learns from colleague Dormont (Mauvaise graine's Jean Wall) and Paris inspector Chambon (The Fall of the House of Usher's Jean Debucourt) that they have no clues and the suspect they conjecture is exactly as he intended when he reveals to Madeleine his deed and how he has implicated her in it. Aubignac stirs up the fear and curiosity of local readers, playing up the notion of a genius killer and the perfect murder when another opportunity presents itself for Ancelin to demonstrate his intellectual superiority under the noses of the constabulary and those closes to him who would never suspect him. Although he had dabbled in policier throughout his prolific career of nearly fifty films in thirty years, with Not Guilty director Henri Decoin (Chnouf) seems to have been taking a cue from his Strangers in the House and Un soir de rafle co-writer Henri-Georges Clouzot's controversial Le corbeau as an example of the "provincial noir" exposing the smug complacency and hypocrisy of idealized French village life. Whereas some examples of this sub-genre like the Clouzot film have as their backdrop the Nazi occupation and French collaboration – even some of Claude Chabrol's later Vichy-set bourgeois thrillers like 2003's Flower of Evil have families with pasts overshadowed by this specter – Decoin's film takes the perspective of not a potential victim or a likely scapegoat but of someone who would seem to possess the professional qualities of his colleagues but is only respected by those who need his services. He is otherwise quietly ostracized, talked about behind his back, tolerated if he were to impose himself on them socially, not invited to the Provincial Medical Association because "we really didn't think it would interest you. You lead such an independent life, so far removed from a conventional life, that it seemed to us that it wasn't such a great idea." He is the kind of person who has time to seethe. It is easy to sympathize with him driven to alcoholism by their derision of him tending to a wounded dog in the street which seems just a step removed from their contempt for his rural patients, and a later argument reveals that there is a longstanding resentment because he defended a quack who nevertheless succeeded in treating several people during an epidemic. On the other hand, when he is introduced, he is drinking because he has lost another patient, "lost" as in their family has requested they be treated by one of his posh colleagues. He shows no remorse in covering up the accident and already seems proud of himself as he presses Aubignac, Louvet, and Chambon for anything that might disprove the conclusions they have drawn from the way he has set up the crimes. His murder of the mechanic would seem to be a crime of passion but for how he has gone about it rather than just reacting in the aftermath. Although he acknowleges that he dislikes Dormont as much as the other man dislikes him, Ancelin seems to have no initial intent to murder him even though he potentially has information about the case he has not told the inspector; Dormont's arrogance simply makes it easier after he has served a useful purpose in giving a second opinion on one of Ancelin's patients that agrees with his own. When he tells Madeleine of how he intended to kill her after her lover, it turns out to be yet another masterful manipulation as revealed in the climax that would be the culmination of his perfect crimes if not for his remorse. Outside of his patients, even those somewhat on friendly terms with Ancelin also reveal themselves to be rotten, from the cafe owner who does not care if he drinks himself to death so long as he pays – and it will take a lot longer since she waters down the brandy not for his sake but to get more out of him – and Aubignac who is more excited about his circulation than the moral panic (although he observes to Ancelin that the locals who gather in the square are more pruriently curious than scared) to gendarme Louvet, Inspector Chambon and his partner (The Devil's Daughter's Henri Charrett) who are resolute in their conclusions that he is unable to convince them otherwise of what he has engineered; indeed, their summation indirectly condemns Ancelin in describing it as a "woman's crime, committed for a woman's motives […] The technical perfection of the two murders would not be possible for a good person like you. It's the work of a brain that's lucid, sharp, precise, quick," and nothing will convince anyone that he is anything but a fool (one wonders if Juraj Herz had seen the participation of a beloved cat in the film's final irony seems to have informed the ending of Herz's loose adaptation of the novel Morgiana). The Lost One: Vaccinating refugees awaiting repatriation in a camp in some far flung area of Europe in the aftermath of the war, Dr. Neumeister gets a shocking reminder of his past life as researcher in Hamburg known as Dr. Karl Rothe (Mad Love's Peter Lorre) with the arrival accompanying medical supplies of chemist Nowak who Rothe once knew as Hösch (Sorcerer's Karl John) looking to call in a favor. Over drinks after hours in the camp canteen, Rothe reveals that he has been waiting for some time to repay Hösch. Flashing back to the 1943, Rothe recalls the visit to his lab by Colonel Winkler (Alibi's Helmuth Rudolph) whose interest in his work was a seeming pretense for assistant Hösch to reveal himself as a Gestapo officer whose spying and seduction of Rothe's fiancee Inge (Afraid to Love's Renate Mannhardt) absolves him of any complicity her forwarding his transcribed notes to the Allies through her father in Stockholm. Although Winkler seems to dismiss the matter as "silly" after having put a stop to it, Hösch needles Rothe about his fiancee's faithlessness and opportunism. Rothe returns to the house of Inge's mother (Possession's Johanna Hofer) where he is renting rooms and treats Inge coldly. When she attempts to be intimate with him, Rothe snaps and strangles her with her own pearls. Hösch, who has tried to call him several times that night, arrives upon the scene and arranges a cover-up with the help of Winkler with just a phone call; whereupon, Inge's death is ruled a suicide. Rather than feeling relief and moving on with his life, Rothe is guilted into remaining the tenant of his dead fiancee's mother and keeps Inge's broken necklace on him as a morbid keepsake. The rot of his complicity with Winkler and Hösch starts to creep into his mind along with something else when Inge's mother takes in a pretty and flirtatious new tenant in Ursula (The American Soldier's Eva-Ingeborg Scholz) awakening in him intertwined impulse of lust and murder. With nearly two decades between Lorre's directorial debut here and his "official" motion picture debut in Fritz Lang's seminal M and much of those years between spent in Hollywood in frustration as a character actor in horror and America's brand of film noir, Lorre's return to Germany with The Lost One seems informed by both of stages of his career that typecast the actor lauded by both Bertolt Brecht and Charlie Chaplin along with his experience of the stark contrast between the post-WWI Weimar and an early post-WWII Germany of reconstruction and historical amnesia. Lorre not having experienced Germany during this period could indeed be said to suit his character as a researcher with no interest or even knowledge of the degree of government oversight in his research – reading blurbs online or even on the disc cover, one gets the impression that Rothe is conducting top secret or Mengele-esque experiments rather than work whose results are no big deal in themselves in which Winkler can only conjecture a vague potential for weaponization – and his quiet home life with a much younger fiancee with seemingly no insecurity of the age gap and the possibility of her falling for someone else until the revelation of her betrayals romantically and professionally cause him to look inward and find darkness. Whether the revelation seems to have triggered a buried sexual mania rather than being a guilt-ridden reaction to the killing and getting away with it – causing him to identify with the role of "death bringer" shouted by a potential victim (The Blum Affair's Gisela Trowe) – he tries to escape it by not only erasing himself but attempting to do so with the other two germs in the Petri dish leading to a climax set during the bombing of Hamburg – in which he does not take part in the action but rather views it in the same detached manner as the camera – during which he dispenses with his fetish necklace and acquires a new more lethal keepsake and waits to be found again. As co-writer, director, and star, Lorre gets opportunities to be more than a "face-maker" conveying his character's psychosis through a more gradual urbane hostility rather than a climactic set-piece. The film's visuals are also informed by German Expressionism filtered through American film noir with chiaroscuro lighting and visual motifs like silhouettes viewed from either side of the glass windows of a set of doors blocked on either side by furniture – the house having been divided into rooms for boarders – Lorre as a tiny figure in stark landscapes, and the bookending images of a train that passes the camp. The film was a flop, perhaps as much being made for a German audience that wanted to look forward rather than being an American or British production primarily for those audiences, and Lorre returned to character roles in Hollywood including four of his last roles in American International drive-in films that put him in the company of Vincent Price and Boris Karloff in a more comic horror vein. Girl with Hyacinths: Novelist Anders Wikner (The Day the Clown Cried's Ulf Palme) and his wife Britt (Thirst's Birgit Tengroth) wake up to a visit by police inspector Lövgren (Björn Berglund) who reveals that their neighbor across the hall Dagmar Brink (The Girl from the Third Row's Eva Henning) has hung herself and left a letter addressed to them. Anders claims not to have known her that well, and the letter confirms this as an informal last will and testament leaving her belongings to do with as they wish and her bank book to pay for her funeral in the absence of any family or friends. While Lövgren is satisfied with the suicide verdict, Anders starts to form an image of his neighbor and her seeming high principles from her belongings, particularly an underlined poem: "Silent shall I be all my life, Determined to find the people "responsible" for Dagmar's suicide, he starts looking into the people who knew her starting with those who were present at the sparsely-attended funeral including banker van Lieven (Gösta Cederlund) who claims to have been a friend of Dagmar's mother and only met her on one contentious occasion, and actress Gullan Wiklund (Prison's Marianne Löfgren) who lived in Dagmar's apartment before her and let her take the girl take over the lease when she first arrived in the city following her mother's death. Anders and Britt also meet Dagmar's estranged husband Captain Brink (The Best Intentions' Keve Hjelm) who always felt she was keeping something from him and alienated himself from her just months into their four year marriage when he discovered a love letter from a man named Alex in Paris just as the Nazis occupied France. A newspaper clipping keepsake of Dagmar's reveals her to have been the model for the painting "Girl with Hyacinths" whose alcoholic painter Elias Körner (Cries and Whispers' Anders Ek) sheds more light on the romantic life of "Miss Lonely" along with vain crooner Willy Borge ('s Karl-Arne Holmsten) who believes he knows the reason Dagmar took her life and relates the events of a gathering on her last night at his apartment including her reunion with an old schoolmate (Anne-Marie Brunius). Britt has been typing up Anders' notes and served as a sounding board for his ideas, but she shocks him by revealing her own piece of the puzzle. Written and directed by Hasse Ekman, a Swedish actor-turned-director who was overshadowed internationally by Ingmar Bergman – in whose early films Sawdust and Tinsel, Thirst, and Prison Ekman appeared in major roles, the latter two with Henning to whom he was married from 1946 to 1953 – but well-regarded in Sweden for a diverse filmography of popular cinema including musicals, comedies, and civic "propganda" films, Girl with Hyacinths is a rare example of Swedish film noir that plays a bit like a hybrid of Laura and Citizen Kane with "Alex" in place of "Rosebud" but the solution is a gut punch that will cause the viewer to look back on things that were perhaps always evident but misinterpreted as well as ponder the effect of the revelation on its discoverer and their choice not to reveal it. Just as Dagmar is absent from the story proper, perhaps a man she does not even know Anders is the last to let her down by trying to find the real person behind the perceptions of others and then becoming disappointed and dismissive when the apparent motives for her suicide seem ordinary. Even if there were not a final reveal to come, his attitude towards what he thinks is the solution seems almost cruel given the real emotions behind a story a writer might find mundane ("If you kill yourself over him, you're nothing special, at best. The mystery that never was has been solved"); as such, perhaps the ones who learn the truth, both the other character and the audience, might feel he is undeserving of the truth much less satisfactory closure – particularly when one considers how he might "exploit" this truth as a "novel" twist – that makes his desire "to find the people responsible for her death" seem less about justice than his own intellectual curiosity and further robs Dagmar of her own choice. By necessity of the narrative, Henning gives a largely sphinx-like performance of ambiguity as recollected by others, with Ingrid Berman's rival Tengroth providing the film's warmth, humor, and compassion.

Video

Although Not Guilty was released in the United States in 1948 in a subtitled edition – and seemingly not at all in the United Kingdom until this Blu-ray edition – we do not know if the export version did indeed include the film's alternate ending that TF1 rediscovered when doing their 4K restoration which debuted on Blu-ray in France in 2019 (the film had an earlier release in 2012). The 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen transfer is the cleanest-looking of the three restorations in the set but the nitrate source will always be slightly grainier even in the sharpest, most well-exposed shots, with the night exteriors looking darker and less "sculpted" in terms of lighting than the more noir-ish interior scenes – cinematographer Jacques Lemare (The Rules of the Game) does some interesting things with lighting here including projecting the patterns of dusk light through a lace curtain onto the interior of the farmer's kitchen when Ancelin and Dormont visit – while some optical effects and ramped up framerate shots look a tad coarser than the surrounding footage. The disc uses branching to present the film with both its original ending (98:51) and the alternate ending (94:22), the latter footage in slightly inferior condition. Although The Lost One was released in West Germany and several European countries, it did not get a release in the United States until 1984 and not until now in the U.K. with this Blu-ray – the film with the same title in the BBFC database is a year early at 1950 and was actually the Italian La signora dalle camelie as presumably Columbia Pictures thought there were enough adaptations of the Dumas tale under some variation of "Camille" – and Radiance Films describers their 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen Blu-ray as coming from a "High-Definition digital transfer" which is presumably what Filmjuwelen released on Blu-ray in Germany in 2019 (an edition which included two lengthy archival documentaries on Lorre and the film previously included on the DVD from Kinowelt's – later Studio Canal's – Arthaus line) along with the barebones Spanish Blu-ray. There are no specifics for the materials which might be a composite of sources with the credits looking coarse and softer – more so than one would expect of opticals although the overall processing might have been effected by budget issues – while medium and close shots look relatively noir-ish but wider shots give the sense of a film about two decades older without the East German excuse of films around this time relying on Soviet stock. Fine damage has not been scrubbed away but we do not know just how much clean-up has actually been employed. Girl with Hyacinths was not released in the United States until a 2015 MoMA screening and not in the United Kingdom until this Blu-ray edition. Swedish label Studio S released a two-disc special edition DVD and in 2020 debuted a Svensk Filmindustri 2K restoration of the original interpositive on Blu-ray in a double feature with Ekman's Fram för lilla Märta. The 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.37:1 pillarboxed fullscreen Blu-ray comes from the same master and the cinematography shares the look of its Svensk Filmindustri studio contemporaries – Bergman fans might liken it to the look of his earlier Gunnar Fischer-lensed films versus the later, starker Sven Nykvist works – with a wider range of grays and more restrained blacks and highlights along with some glamour treatment to Henning's close-ups.

Audio

Out of the three films in the set, Not Guilty is the only one with a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 lossless mono track. The film is post-dubbed and the dialogue can sound divorced from the surrounding sounds – although the sound design is not particularly layered – and it is hard to tell if the original score recordings or the condition of the mixed audio track is responsible for some harshness in the scoring during the credits (the rest of the score tends to be mixed lower) but background hiss has largely been reduced but not removed and rises with the volume of the dialogue. The Lost One's German LPCM 2.0 mono track is post-dubbed and the dialogue is always clear – there is quite a bit of narration including a passage late in the film where the interjection of another character blurs the recollection – while effects are generally sparse apart from the noises of the lab, the climactic action scenes, and the final shot. Music is employed for the credits and a few dramatic passages as well as the action climax. Background hiss is evident but not distracting. Girl with Hyacinths' Swedish LPCM 2.0 mono track is sourced from 35mm optical elements and does not fare as well as the picture restoration, being the kind of track that can be near silent in some passages and then have hiss that rises with the music, effects, or dialogue and one particularly damaged passage late in the film. With both the LPCM 2.0 mono tracks, be sure to turn off any virtual surround or 3D audio option as they just make the background hiss more prominent.

Extras

Not Guilty's extras start with "The Perfect Crime: Henri Decoin and Not Guilty" (25:25), a visual essay by critic Imogen Sara Smith who discusses the careers of Decoin and Simon, noting that Decoin's career has critically suffered from attacks by the Cahiers du Cinema crowd on "Cinema de papa" that saw such directors as craftsmen, with filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier (Death Watch) arguing that he was indeed an auteur and Smith offering up support in discussing the film and his other policier efforts, compares the film to Clouzot's Le corbeau, and the career of Simon including other films where he played scapegoats and outsiders. Smith also discusses the film's two endings, including story elements that actually support the alternate ending as well as also noting that both endings have parallels in the endings of Fritz Lang's Scarlet Street and The Woman in the Window. The disc also includes a 1947 radio interview with actor Michel Simon (13:01) featuring comments from Decoin as well, a 1947 behind-the-scenes radio documentary (8:27) featuring interviews with observers gathered in one of the Chartres town squares to observe the shooting of exterior scenes for the film and get a glimpse of Simon, as well as the alternate ending (3:17) presented on its own, and a photo gallery of four images. The Lost One is accompanied by an audio commentary by critic and programmer Tony Rayns who discusses Lorre's career as an actor on stage and screen in Germany and then in Hollywood, his lifelong morphine addiction and his return to Germany after declaring bankruptcy in the States. He was in a sanatorium being treated for his addiction when he started developing a feature hoping to recapture his early potential as a leading man, with Rayns revealing that the project initially started out as an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant's "The Horla" and argues that some elements still survive in the film which took off when Lorre read of a doctor who had shot his assistant and that both of them were working under assumed names – their actual names being Rothe and Hösch in real life – the difficulties of the cast in contending with Lorre's smoking and his desire for improvisation of a multi-author script that was never really finalized. Rayns also offers his assessment of Lorre's sole directorial effort and the reasons it might have flopped with German audiences given the state of the divided country following the war. Also included is an interview with critic and historian Pamela Hutchinson (23:41) who focuses more on Lorre's career in Germany and then Hollywood – noting that Columbia did not know what to do with him and loaned him out to MGM for Mad Love which was a lead role but further cemented his typecasting – his horror roles and his more rewarding collaborations with Humphrey Bogart at Warner Bros. (including Beat the Devil following his return from Germany). Of The Lost One, Hutchinson discusses the parallels Lorre must have seen between the Germany of M and of the Nazi regime before discussing his latter days in Hollywood along with his daughter's near-fatal encounter with the Hillside Stranglers a decade after Lorre's death. There is also an interview with programmer and historian Margaret Deriaz (18:44) focusing on the criss-crossing influences of German Expressionism and American Noir – through the many German filmmakers who fled the Nazis – on each other and both Germany's post-war noir in both the West and the East as well as official attitudes of the Nazis and the postwar governments on the genre and noir efforts on both sides (including Wolfgang Staudte's The Murderers Are Among Us which is part of Eureka's recent Wrack and Ruin: The Rubble Film at DEFA set). Deriaz also suggests that the film was not a product of his time, comparing it more favorably with the Fassbender's early efforts nearly two decades later along with Veronika Voss and the neo-noir of the Oberhausen Manifesto West German filmmakers. The disc closes with the film's theatrical trailer (2:24) Girl with Hyacinths is accompanied by an audio commentary by film historian Peter Jilmstad who discusses the career of Ekman who started out as a child actor with his father – including a role in the Swedish Intermezzo that lead to Ingrid Bergman being discovered by Hollywood – along with her Swedish career in relation to that of Tengroth – his brief stint in Hollywood, his rivalry as director with Ingmar Bergman, and his marriage to Henning. Jilmstad also discusses the other lesser-known cast members, script changes compared to the film – including the removal of the funeral scene to hold back the identities of some of the characters Anders meets later, as well as the flashback structure inspired by Ekman's admiration of Citizen Kane. "Meeting with Hasse" (63:47) is a cozy 1993 TV documentary on Ekman who discusses his career, his co-writers, and the changeover when Svensk Filmindustri stopped having actor contracts which allowed him and others to cast their films with theatrical actors even in smaller roles rather than filling them in with members of the company. He also discusses his comedies and musicals and is pleasantly surprised by the interviewers with a listen to a pop cover of the lyrics from one of his films, as well as the roles he took in his films with discussion of Girl with Hyacinths reserved for roughly the last ten minutes. "Golden Streaks in My Blood: Seeing and Not Seeing in Girl with Hyacinths" (11:28) is a visual essay by author Julia Armfield arguing that the ending of the film might not have been such a shock for Swedish audiences, or at least members who recognized the queer coding, and looks at moments which seem to support Dagmar's own assertion that there is no mystery to her.

Packaging

The three discs are housed in a limited edition of 3,000 copies presented in a rigid box with full-height Scanavo cases for each film and removable OBI strip leaving packaging free of certificates and markings, reversible sleeves featuring original and newly commissioned artwork, and an 80-page perfect bound book featuring archival pieces and new writing by critics and experts including Farran Nehme, Martyn Waites, Elena Lazic, Jourdain Searles, and more (none of which were supplied for review).

Overall

Radiance Films' post-war World Noir Vol. 3 boxed set presents three fascinating discoveries including the sole directorial effort of Peter Lorre, an example of French "provincial noir" from one of the directors dismissed by the New Wave as part of the "Cinema de papa", and a pre-pre-"Nordic Noir" surprise from a prolific director whose career encompassed both Bergmans.

|

|||||

|