|

|

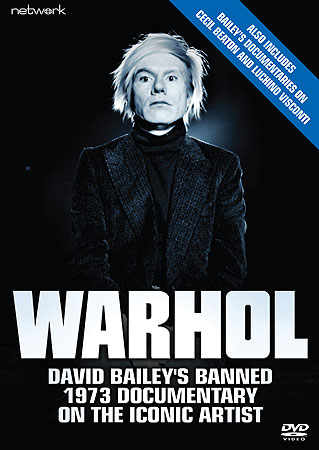

Warhol (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th January 2010). |

|

The Show

Produced for Lew Grade’s ATV in 1972 and intended for broadcast on ITV in 1973, this documentary (produced by David Bailey and directed by William Verity) provoked a significant controversy on its completion. Bailey originally proposed the documentary to ATV in 1971 but the proposal was turned down because the ATV executives bizarrely thought that Warhol was ‘not sufficiently well known’ to justify the production of a documentary about his work (Walker, 1993: 103). In 1972, the project was greenlit and Bailey travelled to Warhol’s Factory, accompanied by William Verity, two cameramen and two sound engineers; there, Bailey and his crew shot 32,000 feet of film (ibid.). Following the completion of the film, a rough cut was submitted to the Independent Broadcasting Authority who demanded the removal of several scenes before the documentary was considered to be fit for broadcast; the documentary was scheduled to be broadcast in January of 1973, as part of ITV’s Tuesday Documentary strand. However, author Ross McWhirter (a member of the conservative National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association) obtained an interim injunction preventing the transmission of the film, which was the NVLA claimed was indecent (ibid.). McWhirter had not actually seen the film but was responding to newspaper reports which had described the documentary as ‘pornographic’ (Weisbrod et al, 1978: 528). Following the hearing on the permanent injunction that McWhirter was seeking, the court found that the IBA had not been irresponsible in deeming the film fit for broadcast, and the documentary was eventually screened in March, 1973 (ibid.). The documentary attempts to mimic the postmodern bricolage style of Warhol’s art: the documentary’s director, William Verity, claimed that the film was intended to ‘amuse and confuse’ (quoted in Walker, op cit.: 103). To this end the editing is filled with non-sequiturs, the documentary frequently shifting gears and changing topic. At the time of its original broadcast, this led to criticisms that the film was nothing more than an ‘arbitrary patchwork’ (unknown critic, quoted in ibid.). However, there is no denying the impact of some of the imagery in the documentary: in a 2002 article for The New Statesman, Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Holly Johnson asserted that ‘[t]he memory of a bare-breasted Brigid Berlin photographing paper American flags as she flushed them down the toilet, and Warhol miming answers to Bailey's questions, became for me television images as unforgettable as the first moon landing or Olga Korbut's backwards somersaults on the bar’ (Johnson, 2002: en).

Warhol opens with a voiceover and title card, which declares that 'Warhol and his followers do not think or live in a conventional way. Some people may find his work or his lifestyle unsympathetic or offensive: it is sometimes difficult to discover where reality ends and fantasy begins. This film is an attempt to capture the spirit of Warhol using some of the techniques he has pioneered'. (In retrospect, this title card seems like an attempt to deflect some of the criticisms of the documentary’s content, and it would be interesting to know exactly when it was added to the film.) Following this, the film opens with a man impersonating Warhol, declaring to the camera that 'Machines have less problems. I'd like to be a machine, wouldn't you'. The same disconnected ‘talking head’ appears intermittently throughout the documentary, delivering pithy aphoristic assertions that are often attributed to Warhol ('The interviewer should just tell me the words he wants me to say, and I'll repeat them after him'; 'I love Los Angeles, I love Hollywood. They're beautiful. Everybody's plastic. But I love plastic: I want to be plastic').

For much of the film’s running time, Bailey interviews Warhol’s collaborators, including Warhol’s close friend Brigid Berlin who, highlighting the playful irony in Warhol’s attitude towards the art world, at one point tells us that 'Andy, he doesn't believe in art, yet he sneaks away to Switzerland to do prints'. When Bailey interviews Warhol, Warhol comes across as a depthless waxwork: at one point, he literally acts as a ventriloquist’s dummy, one of his associates responding to the questions Bailey directs at Warhol whilst Warhol mouths the words. Later, when asked by Bailey if Elvis Presley represented a fantasy for the young Warhol, Warhol asserts that he spent most of his youth 'playing with dolls'. Although some of Warhol’s collaborators’ comments verge on the sycophantic, there are some insightful reflections here, mostly by admirers of Warhol. One of the contributors notes that 'You don't quite think of him [Warhol] as a painter: he's really a media artist, the media being the bridge between art and life. This was Andy's whole thing [….] His message is the media, and the technique is the star'. In light of this, it seems inevitable that Warhol’s interest in the concept of ‘stars’ and his fascination with classical Hollywood cinema would drive him away from painting towards filmmaking. A good proportion of the running time of this documentary focuses on Warhol’s involvement in films, which Warhol claims he switched to simply because he 'bought a [film] camera, and the camera seemed to be so much easier than the painting'. At one point, Bailey asks Warhol if he doesn't 'have a fantasy of making a five million dollar movie with Liz Taylor', and Warhol dryly asserts that 'Yeah, we have a fantasy of making a five million dollar movie with Liz Taylor, but we'd make it on four hundred dollars and keep the rest of the money'. Later, Warhol claims that in 1971 he ventured to Paris and met classical Hollywood stars including Claudette Colbert, Simone Simon, Ginger Rogers, Simone Signoret and Olivia de Havilland; Warhol tells Bailey that 'I was just surprised that they were all so short and they had big heads, or they had big heads and they were all so small... their bodies were short, but their heads were big. And I never realised that that's the reason why the Hollywood stars were all so great, because that's the magic they gave on screen because they really came out so much better [….] Tall people can't really make it as well as short people can'. Warhol also intriguingly tells Bailey that the reason his own films acquired the label ‘underground films’ was because they were initially screened in basements and cellars.

Some of the highlights of the documentary include some behind-the-scenes footage of Paul Morrissey directing transsexual Factory ‘superstar’ Candy Darling in Women in Revolt. The mercurial Morrissey offers some fascinating, and characteristically left-field, assertions about The Factory’s films, suggesting that The Factory’s approach to filmmaking was a reaction against the dominance of the auteur principle and the privileging of the director in 1960s film culture. Morrissey asserts that that 'Everyone tries to make films very well nowadays, but we go in the opposite direction: we try to make them as badly as possible, a little bit in the tradition of the Carry On films. And we find that if we put direction in the films, that gets in the way of the cast; and we're only interested in the cast and whatever they do. As long as they keep talking and, er, you know, taking the burden of film on their personality really. And we like that. In the meantime, we keep the direction out of it. I mean, directors in film today are the established... they're running the ship now. It's easy to direct, if you want to direct; but when you direct films, you lose them. You lose a lot of qualities in them... You lose a lot of the old qualities that Hollywood gave us, which were stars. So we look for stars and let them do what they want'.

Later, Candy Darling cites Lana Turner’s role in The Prodigal (Richard Thorpe, 1955) as an inspiration, declaring that her love of the movie led her to 'fill up the bathtub and put blue food colouring in the bathtub to make the water blue, like in Technicolor; and for a time I was Lana Turner in The Prodigal'. In reaction to this, Morrissey states that 'I think that what Candy says is very interesting. I think that film stars inspire people to do very irrational things, which I don't think that a director will ever be able to do. And I don't think directors will ever influence young people. Directors influence people who read about films and dote on the technicalities of filmmaking, and it's all a very snobbish, trashy kind of intellectual appeal, the notion of directors in cinema. By letting the cast make up their own dialogue and their own stories, as much as possible, you keep out a lot of meaning from the film. As soon as you start to put meaning into a film, you do it with the story; and if the story gets twisted in the process, it doesn't have much meaning – it remains very superficial. But that's a trick to itself, and I think we've been trying to do that all along. We've always been a little bit bothered if somebody starts to act real in front of the camera'.

Warhol spends some time dispassionately discussing his shooting by Valerie Solanos in 1968, telling Bailey that he ‘was just in the wrong place at the right time’. Warhol’s business manager, Fred Hughes, discusses in detail the day that Solanos shot Warhol, suggesting that Solanos’ association with Warhol began when Solanos was recommended to Warhol by ‘a well-known writer’ and inferring that Solanos’ attempt to take Warhol’s life was precipitated by an argument she had with Paul Morrissey. The interviews serve to present Warhol as an elusive, fragile figure who is somewhat ambivalent towards his hangers-on: when Bailey refers to some of Warhol’s superstars as ‘drag queens’, Warhol corrects him by asserting that 'The people we use aren't really drag queens. Drag queens just sort of dress up […] and the kind of people we use think they're really girls and stuff, so that's sort of different [….] These drag queens complain about all their problems and stuff, but they don't really know what girls go through: I mean, they've never had a period'. (However, it’s difficult to determine how much Warhol’s personality, and his attitudes towards his associates, changed following Solanos’ attempt on his life.) Tellingly, at one point we’re told that ‘Andy’s greatest work has been this myth that he's perpetuated about himself, the myth of Andy Warhol, and it really has sort of created a subculture'. Overall, the impression of Warhol is that the man himself was something of a blank canvas on which people projected aspects of their personalities, much as his art used ‘found’ images and objects and offered a perverse reflection of them. Perhaps most tellingly, one of the interviewees tells us that 'It's fun to talk to Andy, because it's sort of like talking to nothing. Because you just keep talking and he never says anything: you just go on and on, and you keep talking and he just goes “Hmmm” [….] So that makes it more fun, because it's almost like talking to yourself'.

Bailey’s approach to his subject is objective: there is little authorial intervention, and Bailey tends to let his subjects speak for themselves. For many scenes, the camera is simply an observer, as in the footage shot during the production of Women in Revolt, which shows Morrissey directing the film whilst Warhol sits to one side with a sly grin on his face. Warhol has alternately been positioned as the naïve puppet of his collaborators and the arch-manipulator of the artificial environment that was The Factory, and this particular scene – with its ambiguity about whether the passive, silent Warhol or the active, vocal Morrissey is in control – seems to capture the ambiguity at the heart of Warhol’s public persona.

Video

All three documentaries seem to have been shot on 16mm. Warhol looks fantastic, having apparently been subjected to careful restoration. Colours are natural, and the image is detailed. The grain of the 16mm stock has been preserved. Beaton By Bailey seems to have undergone some restoration too. Count Luchino Visconti of Modrone is in the worst condition, although it is by no means less than watchable. The original break bumpers are intact, and the documentaries are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monophonic track. This is functional; there are no major problems. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The DVD includes two other documentaries by Bailey: - Beaton By Bailey (1971) (52:13)

Opening with footage of Bailey taking still photographs of photographer and designer Cecil Beaton, Beaton By Bailey begins with Beaton reflecting on his youth, before friends and colleagues discuss Beaton’s eccentric dress sense: Lord David Cecil states that ‘He’s always been very gaily dressed [….] His clothes are very characteristic’. Bailey and Beaton discuss some of Beaton’s images, including his famous portraits of Greta Garbo and Marilyn Monroe; Bailey and Beaton observe that in Beaton’s early photographs ‘[t]he background’s more important, almost, than the sitter’. Beaton agrees that the images could be described as ‘Very camp. Oh, yes. High camp’. Some footage of Beaton at work is deployed throughout the documentary.

Marit Allen suggests that Beaton ‘has a totally different relationship with the model than most photographers I’ve worked with’. She also adds that the aristocratic Beaton’s ‘social climate and social background is completely different from the people I’m used to working with’, declaring that his pictures ‘have a fairy tale quality; they have a reality all of their own, full of the things that Mr Beaton likes like flowers and beautiful interiors, beautiful gardens, beautiful lawns, beautiful days’. On the other hand, Twiggy’s manager Justin de Villeneuve claims that he disliked the photographs that Beaton took of Twiggy: ‘I thought he’d do a very nostalgic, Twenties-looking type of photograph, but instead he seems to have been influenced by Twiggy [….] I hated the pictures. It was a shame, because he was capable, more than anyone else, of doing very great, great pictures of Twiggy’.

Truman Capote suggests that Beaton ‘has a kind of social vanity that is amusing and unique […] and is part of his charm’. Capote infers that Beaton has an unfulfilled desire to become a playwright, and argues that Beaton would have liked to have been compared with Noel Coward. Immediately after a scene in which Beaton is shown rudely ignoring a waiter at a hotel restaurant, Capote observes that ‘he certainly goes to extremes. He can be extremely kind or extremely rude. He can be the rudest person I’ve ever known [….] He certainly gathers enemies like other people gather roses [….] He positively loves you or he positively hates you’.

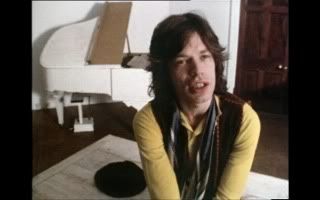

Jean Shrimpton suggests that she found it difficult to communicate with Beaton, and Mick Jagger affects a mock imitation of Beaton’s upper middle class diction to deliver a ridiculous story about his first meeting with Beaton ‘in 1926, in a part of Morocco which was little known then’ – before asserting ‘I can’t remember any stories like that about him. I did actually meet him on a dark night in a very narrow street, and he was in a crowd of people and an old Russian lady’. Jagger then adds dryly that ‘He’s very nice. He takes some nice pictures’.

Beaton does his best to come across as a thoroughly likeable man, but the documentary seems to subtly suggest that there is a darker side to his personality, as hinted in the juxtaposition of Beaton’s rude treatment of the waiter and Capote’s suggestion that Beaton ‘can be extremely kind or extremely rude’. Bailey’s unobtrusive style lets the subjects speak for themselves, and we get a variety of perspectives on Beaton’s work and personality, with Jagger’s satirical skewering of Beaton’s public persona (and Shrimpton's polite refusal to discuss Beaton) perhaps being the most telling. - Count Luchino Visconti of Modrone (1972) (27:09)

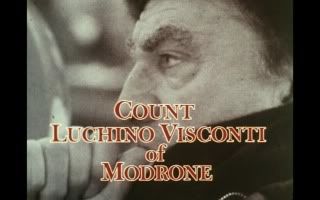

Made during the production of Luchino Visconti’s 1972 film Ludwig, a biopic of the life of Bavarian ‘Mad King’ Ludwig II, this half-hour documentary features extensive interviews with Visconti, alongside comments from actors Helmut Berger and Romy Schneider. Most of the comments are focused on Ludwig, with Visconti claiming that the inspiration for the film came when he was doing location scouting for The Damned (1969); Visconti also claims that he chose Berger as the star before beginning work on the project.

Other than his comments on Ludwig, Visconti discusses his career and his problems with the Fascists during the Second World War. He reveals that he was jailed for three months by the Fascists, who planned to execute him for his association with the Communist party and his work with the resistance. Visconti discusses the censorship of his first film Ossessione/Obsession (1943) by the Fascists, who prevented the film from being screened in Italy until after the war; he also talks about Ossessione’s importance in establishing the Neo-Realist movement in Italian cinema. Bailey also encourages Visconti to discuss his shift in focus with 1954’s Senso, away from Neo-Realism and towards films that are often described as ‘novelistic’ (such as Il gattopardo/The Leopard, 1963).

On the set of Ludwig, Helmut Berger – who was once Visconti’s lover – claims that Visconti is 'the greatest director on the continent, because the atmosphere, how he's treating the actors, is very enchanting and at the same time he's very tough and very demanding. I think that he's a genius [….] He's very demanding. You really have to work very hard and very concentrated'. However, Berger – who was a rising star at the time and who was also known to be somewhat unpredictable and egotistical – reveals himself to be a difficult interviewee, and Bailey confronts him on this point. Bailey asks Berger why he is 'so difficult to interview', and Berger responds by stating 'First, I don't like television; second, the less people know about you, the better'. When asked by Bailey if he'd like to be a 'superstar like Michael Caine', Berger asserts that he didn't know that Caine was a 'superstar'; at one point, Berger tells Bailey that a particular query is 'a stupid question' and asserts that 'I'm fed up with the interview, and also I'm very late now', before writing 'END' in the condensation on the inside of the car window in which he and Bailey are travelling.

Bailey also interviews Romy Schneider, with whom Bailey seems to have had some sort of past conflict. Despite this, Schneider reveals herself to be a warm and gracious interviewee. The documentary conveys some interesting nuggets of information. Visconti declares that whilst censorship in Italy has become more relaxed, he believes that censorship of pornographic material is acceptable whilst asserting that political censorship ‘is very bad’. Visconti also reveals that he encounters difficulties when travelling to America, which Bailey suggests may be due to his political leanings: 'They are always a little difficult when I have to go to America. I don't know why'. Visconti also discusses his fascination with decadence, suggesting that decadence 'is a very important movement'; Visconti claims that being labeled as a ‘decadent’ filmmaker is 'not insulting, it's very important to be decadent'. Unfortunately, very little is communicated here that cannot be inferred from Visconti’s films, partly due to Visconti’s broken English and occasionally due to his apparent disinterest in some of Bailey’s questions – which he seems to answer out of a sense of politeness. (On the other hand, Helmut Berger is positively rude to Bailey at times.) Nevertheless, this documentary is fascinating as a view of a type of European cinema that simply does not exist anymore.

Overall

A great release, this DVD set is essentially a reissue of Network’s 2006 Bailey On… DVD, although Warhol has apparently undergone some more digital restoration since that earlier release. Each of the documentaries in this set is watchable, all of them offering different perspectives on several widely-different cultures from the same era: from the Pop Art of Warhol to the conservative Englishness of Beaton and the European art cinema of Visconti. The documentaries are all shot in an objective manner, letting the subjects speak for themselves with little guidance from Bailey. Anyone interested in any of the subjects is likely to find something of interest in this DVD release. References Johnson, Holly, 2002: ‘Pope of Pop’. The New Statesman (25 February, 2002): en Walker, John Albert, 1993: Arts TV: A History of Arts Television In Britain. Indiana University Press Weisbrod, Burton A. et al, 1978: Public Interest Law: An Economic and Institutional Analysis. University of California Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing.

|

|||||

|