|

|

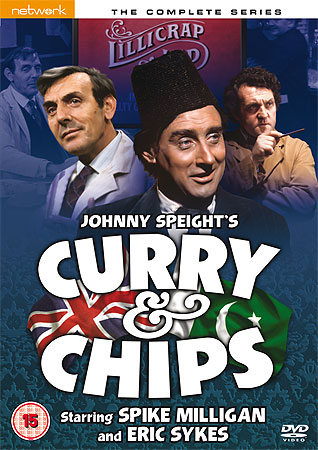

Curry and Chips AKA Curry & Chips (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th April 2010). |

|

The Show

Curry & Chips (LWT, 1969)

The first new sitcom written by Johnny Speight after the development of his most famous creation, Till Death Us Do Part (BBC, 1966-1975), Curry & Chips (LWT, 1969) arguably has the same weaknesses as Till Death Us Do Part. Famously, Speight intended Till Death Us Do Part as a satire of the type of bigotry expressed through the series' protagonist Alf Garnett (Warren Mitchell), but as the show progressed it became clear that part of the audience was laughing along with Garnett’s comments at the expense of, in the character’s words, ‘coons’ and ‘nig nogs’. This was largely due to the fact that within the show, there was little effective opposition to Garnett’s rants, as his wife Elsie (Dandy Nichols) and daughter Rita (Una Stubbs) were both rendered relatively powerless in the face of Garnett’s angry tirades, and his son-in-law Mike (Anthony Booth) – who offered the most combative criticism of Garnett’s bigotry (and, more pertinently, Warren Mitchell’s powerful performance as Garnett) – was an otherwise entirely unsympathetic character, a layabout who used his professed socialist worldview to justify his workshy nature. John Oliver’s biography of Speight, written for the BFI’s ScreenOnline website, describes Curry & Chips in similar terms, as creating ‘a furore equal to if not surpassing that which had greeted Till Death Us Do Part’; Oliver asserts that with Curry & Chips, ‘Speight again professed to be ridiculing racial bigotry, but, without the saving grace of being even remotely funny, its catalogue of repellent characters, general expletives and a distasteful array of slang terms for ethnic minorities, led to its cancellation after just six episodes. Speight's no doubt sincere if somewhat naive intentions had again backfired’ (2003: np). Oliver also notes that Curry & Chips’ central themes are issues of ‘immigration and workplace work relationships’ (ibid.). In Curry & Chips, Spike Milligan plays Kevin O'Grady, a Pakistani man who has an Irish father. O'Grady acquires a job at the British novelty goods manufacturer Lillicrap, Ltd. Working for Lillicrap, O'Grady (less than affectionately nicknamed 'Paki Paddy' by his colleagues) encounters a variety of different characters representing various attitudes towards issues of race, nationality and immigration: the shop steward, Norman (Norman Rossington), is a socialist who is also ironically the loudest voice of bigotry within the firm; the foreman, Blenkinsop (Eric Sykes), is a more liberal-minded man who quickly makes friends with O'Grady but who isn’t above making jokes about issues of race and ethnicity (and who uses terms like ‘wog’ and ‘coon’ without so much as an afterthought); and one of the workers, Kenny (Kenny Sykes), is a British Afro-Carribean who possesses strong anti-immigration views which frequently ally him with Norman.

O'Grady soon makes friends with Blenkinsop, who helps O'Grady navigate his way through the absurdities of British culture. Blenkinsop also helps O’Grady find a room at the lodging house Blenkinsop lives in with his landlady Mrs Bartok (Fanny Carby). Bartok is initially opposed to O’Grady’s presence in her house, due to his ethnicity (and at a time when lodging houses in England infamously asserted ‘No blacks, no Irish, no dogs’); however, Bartok is soon won over by O’Grady, and they quickly become friends. One of the most challenging aspects of Curry & Chips (at least for modern viewers) is that O’Grady is played by a white actor, the great Spike Milligan, who has been ‘blacked up’ for the role. Milligan also gives O’Grady an exaggerated ‘pidgin’ English accent. (Incidentally, the character of O’Grady first appeared in an episode of Till Death Us Do Part, where he was also played by Milligan.) Milligan attempted a similar feat with his 1975 BBC sitcom about multiculturalism, The Melting Pot, in which Milligan once again appeared (alongside John Bird) ‘blacked up’ as a British Asian character. Famously, The Melting Pot was pulled by the BBC after only a single episode had been aired, although six episodes had already been produced for broadcast. However, it has to be noted that the BBC’s long-running The Black and White Minstrel Show, which began broadcasting in 1958, was still on air at the time, and was only cancelled in 1978 – although the show had been controversial since the 1960s, with the black British magazine Flamingo denouncing The Black and White Minstrel Show as ‘outdated and degrading rubbish’ after the series won the Golden Rose of Montreux in 1961 (quoted in Bourne: 5; also see Briggs, 1995: 198). Despite the problematic use of a ‘blacked up’ white actor to play O’Grady, Curry & Chips frequently allows O’Grady to come out ‘on top’, and the episodes go to great lengths to ridicule the prejudices of O’Grady’s workmates and the other people that O’Grady meets. In the first episode, O’Grady visits the local pub with Blenkinsop, and there he encounters a bigoted patron. In an attempt to quell the pub patron’s verbal attack on O’Grady, Blenkinsop tells the man that O’Grady is from Ireland. However, O'Grady corrects him: 'I'm from Pakistan', he asserts. The pub patron responds by sarcastically noting that 'Pakistan is not in Ireland, mate. Pakistan's in India, mate'. O'Grady corrects him: 'Oh, no. Pakistan is not in India, mate. Pakistan's in bloody Pakistan, mate'. In scenes such as this, the viewer is definitely encouraged to laugh at the ignorance of the characters, such as the pub patron, that O’Grady meets.

Throughout the six episodes, Speight uses O’Grady’s status as a cultural outsider as a comic device that enables him to highlight some of more absurd aspects of British society – not just in relation to issues of ethnicity and prejudice, but also on topics such as workplace politics. In the opening episode, O’Grady witnesses the men whistling at one of the women in the canteen. ‘Why do they do that?’ he asks. 'The whistle? That's British; that's chivalry', Blenkinsop tells him, without a hint of irony. In the second episode, O’Grady is at the centre of workplace politicking, when the other workers discover that O’Grady is more productive than them. Norman, the shop steward, complains to Blenkinsop that 'nobody works during their tea break but him. It's one of the unwritten laws of British industry; it's part of our white culture'. When confronted by Blenkinsop, O’Grady observes that 'there are too many men' in Britain who 'go slow', using their toilet breaks to 'smoke cigarette, play cards, look at picture of girls with big Bristol Rovers'. He tells Blenkinsop, 'I don't understand this slow down; I don't understand. I work hard. I work fast, fast, fast, because I want to put Britain back on its feet. I want Britain to get rich again. I think this is very good. But working-class man says, “No, don't work hard for bloody capitalist class”, they say'. Blenkinsop reminds O’Grady that ‘that's the way industry works in this country'. To this, O’Grady dryly observes, 'I see. They work, but not too hard'. O'Grady rightfully suggests that too many British workmen are lazy, but by the end of the episode he concedes that he will have to ‘work my hardest to go slow, like good British workmen’.

In Representing Black Britain (2002), Sarita Malik claims that Speight wrote Curry & Chips in direct response to Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ anti-immigration speech (95). References to Powell’s rhetoric abound throughout the series, with one character, Smelly (Sam Kydd), repeatedly referring to Powell as ‘Eunuch Powell’ - his misappropriation of Powell's name comically deflating his admiration of Powell's ideas about race and immigration. In the first episode, the bigoted pub patron mentioned above asserts that he is ‘with Enoch’, and when Blenkinsop confronts Norman about his prejudices (after Norman refers to Kenny as ‘a black’, Blenkinsop reminds Norman that ‘he's British. He was born in London. He's not black... well, only in colour [….] You're biased, you are. You call yourself a labourite, but you can't stand blacks. You're not a labourite; you're a fascist, you are'), Norman asserts 'I've voted Labour all me life, and me father before me; but when it comes to blacks, I'm with Enoch'. According to Malik, Curry & Chips ‘was illustrative of the standard tone of racial humour that was beginning to emerge’ in the mid to late 1960s and would recur throughout the 1970s, in sitcoms such as Mind Your Language (LWT, 1977-9), Rising Damp (Yorkshire Television, 1974-8) and the notorious Love Thy Neighbour (LWT, 1972-6): ‘it set up a multicultural scenario as the basis for racial tension. The common structure in these comedies featured a racist opponent who was blatantly narrow-minded but delivered the racism most affectionately […] This would usually be counterpoised by a Black character who would underscore the former’s racist attitudes and “put them right”, or alternatively by a White liberal voice who would urge a more empathetic approach towards Black people (ibid.) In following this formula, which would dominate many 1970s sitcoms, Curry & Chips contained a number of ‘stock character-types’ familiar from other comedies throughout this period: ‘an overt racist (Norman, played by Norman Rossington), a Black worker, (Kenny, played by Kenny Lynch), a liberal factory foreman (Arthur, played by Eric Sykes), and, inexplicably, a blacked-up Irish Pakistani (Kevin O’Grady or “Paki Paddy”, played by Spike Milligan)’ (ibid,). For Malik, Milligan’s performance as O’Grady, ‘complete with nodding head and mock pidgin accent (meant to denote an Irish-Asian), represented the kind of bumbling foreigner stereotype that was to be recycled again and again’ in other sitcoms (ibid.). More problematically for Malik, ‘Kenny, the comedy’s only “real” Black character […] was as vehement as the comedy’s other racist characters in his “anti-wog” stance. The relative “acceptability” of the British-born Kenny, as well as enacting a “divide and rule” logic between those “Made in Britain” and “real foreigners”, exploited the differences between Asians and African-Caribbeans, and set up Kenny as a Black “ally” to effectively enable audiences to disclaim their own identification with the racist overtones that ran through the text’ (ibid.). Ultimately, Malik claims that ‘[t]here was something quite surreal, not to mention insulting, about seeing a White comedian blacked-up as a Pakistani (Milligan), who was, in turn, being mocked for his foreignness by a genuinely Black actor (Lynch)’ (95).

Milligan’s appearance in what is effectively ‘blackface’ is arguably anathemic to modern sensibilities, as ‘blacked up’ performances have over the years become taboo. However, since the heyday of the irony-laced ‘alternative comedy’ scene in the 1980s, the problematic concept of ‘blacking up’ has been recuperated, with a heavy investment of postmodern irony which encourages us to laugh at the concept of ‘blacking up’ rather than at the ethnic group that the ‘blacked up’ white actor signifies. As an example, The League of Gentlemen (BBC, 1999-2002) featured a comically-exaggerated ‘blackface’ character, Papa Lazarou (Reece Shearsmith), the leader of the Pandemonium Carnival and a nightmarish figure who, in the words of Leon Hunt (2010), is ‘[p]itched somewhere between Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’s Childcatcher, Freddy Krueger at an Al Jolson convention, and a more mythic trickster archetype’ (137). Similarly, the BBC sketch comedy Little Britain (BBC, 2003-6), known for skewering various stereotypes, parodied ‘blacking up’ in a sketch in which David Walliams donned 'blackface' to play an obese black woman named Desiree; Channel 4’s sitcom Peep Show (2003- ) featured a scene in which one of the main characters, Jeremy (Robert Webb), puts on ‘blackface’ to please his girlfriend who, when Jeremy asserts ‘It just feels […] wrong’, childishly argues ‘We’re breaking a taboo […] We’ve got boundaries to smash’; and more recently, Channel 4’s irreverent show Facejacker (2010) has offered a postmodern appropriation of the ‘blacking up’ phenomenon, with traditional ‘blackface’ make-up being combined with facial prosthetics to allow comedian Kayvan Novak to transform into Ugandan con-man George Agdgdgwngo. Away from British television, the Hollywood comedy Tropic Thunder (Ben Stiller, 2008) offered a provocative satire of the ‘blacking up’ phenomenon too, via Robert Downey Jr’s performance as Kirk Lazarus, a method actor who undergoes surgery to depict an African American character in a film-within-a-film. Most effectively, Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled offers a satirical and savage deconstruction of the ‘blacking up’ phenomenon, and in his commentary track on the DVD release of Bamboozled Lee suggests that the 'black and white minstrel' phenomenon has not come to an end: for Lee, variations of the derogatory minstrel show still abound – in the imagery of Gangsta Rap, for example, whose audience is predominantly white middle-class youth – but the ‘blacking up’/’blackface’ concept has simply disappeared. That ‘blackface’ is taboo, Lee suggests, simply helps to conceal the fact that the racist concepts that underpin blackface minstrelsy circulate, unchallenged, in other forms.

Milligan’s comedy, including his series Q (BBC, 1969-82), is often allied with postmodern humour, for its satirical outlook and its play with existing media forms, and in this sense Curry & Chips can be seen as ahead of its time, anticipating more recent postmodern humour in the way that it satirises ‘blacking up’ and subverts representations of race on television – with a white actor portraying in ‘blackface’ a British-Asian character, and a black British actor, Kenny Lynch, playing a character who holds the kinds of views traditionally associated with white male characters such as Alf Garnett. Alternatively, the series can be seen as offensively ‘old hat’ in its use of ‘blackface’. This is the same dilemma within much of contemporary postmodern comedy, which uses ironic racism supposedly in order to satirise attitudes towards ethnicity. (Comedians associated with this type of humour in the UK include Richard Herring, Jimmy Carr, Al Murray and Ricky Gervais.) Speight was ahead of this game, with his sitcom Till Death Us Do Part, which was intended to satirise Alf Garnett’s prejudiced rants. However, the divided response to Till Death Us Do Part – to which a significant proportion of viewers responded by laughing with Garnett rather than at him – highlights a fundamental problem with this type of humour: it is possible that some members of the audience will fail to recognise the irony and see the material as legitimising their own prejudices. In relation to the aforementioned use of ‘blackface’ in Little Britain, social psychologist Sue Becker asserted that ‘With Little Britain, I’d say half the population are taking it in the way it’s intended [as a satire of social attitudes towards issues such as disability and ethnicity]. Others are just laughing at someone who’s poor and slaggy’ (quoted in Logan, 2009: np). More pointedly, in a notorious television interview with Ricky Gervais, the American comedian Garry Shandling dismissed Gervais as a ‘naughty little boy’ for his use of ironic racism and his combative jokes about disability (in Channel 4’s Ricky Gervais Meets… Garry Shandling, 2006). This is a debate which will continue, but it is a relevant issue to raise in relation to Curry & Chips because for all Speight’s intentions to satirise prejudice (and O’Grady’s tendency to come out ‘on top’ during the series), Curry & Chips arguably falls into the same trap as Till Death Us Do Part – with some viewers seeing the series as a critique of British attitudes towards issues such as race and class, and other viewers seeing the series as a legitimation of racist attitudes, which is apparently the reason for Curry & Chips’ absence from British television screens since its original broadcast in 1969. In his critique of Curry & Chips for the BFI’s ScreenOnline website (2003), Ali Jafaar notes that ‘the criticism levelled against Till Death - that the prejudices of its characters reinforced, rather than challenged, those of its audience - seemed even more pertinent here. It is interesting to note the delighted response of the studio audience to off-hand racist comments’ made by the cast of the sitcom (np). Jafaar pointedly suggests that ‘[t]he treatment of the character Kenny, also of Asian descent, is also intriguing. Spared much of the abuse leveled at Kevin because of his British birth, initially he turns against Kevin. As he remarks to Arthur, "I might be a bit brown, but I'm not a wog like him." It is the casual abandon with which words like 'wog', 'coon' and 'Paki' are endlessly repeated by the characters that is most worrying. Even when attempting to dilute the vitriol with humour, as in Norman's line, "If they sent all the wogs back home, there'd be an extra hour's daylight," there is a distinctly uneasy sense of where the writer's sentiments lie, particularly when viewed through contemporary eyes. Even the sympathetic Arthur, who hires Kevin and frequently comes to his defence, is not above using words like 'wogs' and 'coons'’ (ibid.).

Strangely, in the last two episodes O’Grady is given very little to do, and in the final episode Milligan is almost absent entirely, aside from a few brief appearances – possibly a recognition of the problematic depiction of O'Grady and Milligan's provocative 'blacked up' performance as the character. (However, on its initial broadcast the series was reputedly more controversial for its use of bad language than for its representation of race relations, the Independent Broadcasting Authority supposedly receiving complaints about the frequent use of the word 'bloody'.) Episode One (24:38) Episode Two (23:33) Episode Three (25:26) Episode Four (22:51) Episode Five (23:08) Episode Six (24:34) Extras: Saturday Night Theatre – ‘The Salesman’ (24:38) Image Gallery (00:58)

Video

Shot on video, these episodes display the aesthetic qualities of video material of this vintage – burnt highlights, weak contrast, etc. There is some tape damage to the episodes, but nothing too serious. The break bumpers are intact for all of the episodes, and they are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. The episodes appear to be uncut.

Audio

The episodes are presented with a two-channel mono soundtrack. This is audible and without problems. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes, as an extra feature, an excellent Speight-written episode of Saturday Night Theatre, ‘The Salesman’ (1970) (24:38). In ‘The Salesman’, Ian Holm plays a salesman who arrives at a terraced house carrying a huge case and wearing a black overcoat and fedora. He claims that he 'want[s] to have a chat' about psychiatry with the householder, a blowsy blonde woman named Barbara Simpson (Priscilla Morgan). The woman asserts that she is aware of her vulnerability but lets the salesman into her house anyway: 'There are certain people […] that only have to hear your a girl on your own, and they take advantage, don't they [….] I don't care to be subjected to one of those attacks, like you hear about in the papers', she tells the salesman as she locks him in her house, almost as if she is tempting fate.

'Mad people can be very cunning, you know [….] They can appear completely sane in every way [….] That's the danger with madness: the people who've got it tend to conceal it', the salesman tells her. The salesman claims he works for a company offering 'door to door psychiatry, really', and he offers Mrs Simpson psychiatric treatment with the promise of 'a certificate of sanity' at the end of it. The salesman opens his case and reveals a portable foldaway couch. He asks Mrs Simpson to 'go behind a screen and prepare yourself. Oh, there's no need to remove any garments: it's only a mental examination', he reassures her, his right eye twitching obsessively. When Mrs Simpson refuses to lie on the couch, the salesman pulls a gun on her: 'Don't you get violent with me: I'm a psychiatrist; I'm trained to handle you nutcases', he threatens. The gun at her head, Mrs Simpson lies on the couch. The salesman pulls the trigger of the gun he's holding; it's really a water pistol. He laughs: 'You thought I was going to shoot you, didn't you.. Blimey, the obsessions some of you women have. Never mind, we'll soon straighten you out... Don't move! This isn't the only weapon I've got, you know', he tells her.

The salesman becomes increasingly hysterical; Holm's performance is filled with nervous tics, suggesting a disturbed and obsessive personality. The salesman continues to goad Mrs Simpson, eventually highlighting her 'obsession with fear, all these bolts and chains, fear of being attacked' before pointedly questioning 'Or is it a desire to be attacked by a strange man?' With ‘The Salesman’, Speight has constructed yet another satirical piece: a comic critique of gender relations and the media's obsession with presenting men as predators and women as prey. (In fact, ‘The Salesman’ almost offers a pre-emptive parody of the bodycount pictures/slasher movies that became popular at the end of the 1970s and during the 1980s.) In an arguably chauvinistic way, ‘The Salesman’ suggests that the cultural anxieties that surround men are an example of what Freudian critics might label desublimination. The salesman himself notes that the housewife's 'fear of being attacked' may on some level be 'a desire to be attacked': Mrs Simpson pays lip service to the concept of home safety, but she is more than willing to tempt fate by inviting an strange man into her house. Although ‘The Salesman’ never directly mentions rape, the type of attack that Mrs Simpson fears, and which the salesman represents, is clearly sexual in nature, as the salesman's comment that 'This isn't the only weapon I've got, you know' suggests. Despite being a comic piece, the sense of threat in ‘The Salesman’ is palpable, and in its suggestion that Mrs Simpson is on some level 'asking' to be attacked (or, more directly, sexually assaulted) is no doubt going to confirm for some viewers that Speight's work has little time for women.

The disc also contains an Image Gallery (00:58).

Overall

Curry & Chips is a series that was arguably ahead of its time, in terms of its ironic and self-aware treatment of issues of race relations and racial prejudice. Speight intended the series as a critique of the kinds of views expressed in Enoch Powell's 'Rivers of Blood' speech. However, as with Till Death Us Do Part Speight's intended meaning is sometimes confused and distorted, and ultimately Curry & Chips is another case of well-meaning but perhaps misguided satire from Speight. The terms of racial abuse come thick and fast throughout the six episodes, and it's easy to see that, as with Till Death Us Do Part, for some viewers they may have the opposite effect and in fact offer legitimation to the kinds of attitudes that Speight was intending to deconstruct and ridicule. The decision for Milligan to don 'blackface' to play Kevin O'Grady is questionable, but seems to anticipate the alternative comedy scene's recuperation of non-PC humour and methods. Milligan is a comedian who was often seen to be ahead of his time, and his surreal confrontation of taboo subject matter made him an icon for many of the alternative comedians who dominated television screens from the 1980s onwards; thus, a series such as this is arguably more suited to today's climate than the era of its original broadcast, due to modern comedy's subversive appropriation of jokes about ethnicity and its assumption that its audience is savvy enough to appreciate the irony in, for example, the use of 'blackface' in shows such as The League of Gentlemen. Curry & Chips is actually quite funny in places, contrary to its reputation and despite John Oliver's assertion that the series doesn’t even have 'the saving grace of being even remotely funny' (op cit.). The friendship that develops between Blenkinsop and O'Grady is interesting, and the cast – particularly Eric Sykes – are effective in their roles. There's no doubt that a portion of viewers may find Curry & Chips problematic, but the series is fascinating viewing for the insight it offers into attitudes towards ethnicity, immigration and workplace relationships in the late 1960s. As noted above, Speight makes excellent use of O'Grady's status as a cultural outsider to highlight the follies within British culture. With this in mind, Curry & Chips is an intriguing watch, although there’s no doubt that some viewers may find it challenging and potentially problematic in the way that it confronts the issue of race relations. References: Bourne, Stephen, 2005: Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television. London: Continuum Publishing Briggs, Asa, 1995: The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Vol 5. Oxford University Press Hooper, Mark, 2007: ‘Catch of the day? Is ironic racism still racism?’ The Guardian (20 November, 2007). [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/tvandradioblog/2007/nov/20/catchofthedayisironicrac Hunt, Leon, 2010: ‘The League of Gentlemen’. In: Lavery, David (ed), 2010: The Essential Cult TV Reader. University Press of Kentucky: 134-41 Jafaar, Ali, 2003: ‘Curry & Chips’. ScreenOnline [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/535237/index.html Logan, Brian, 2009: ‘The new offenders of stand-up comedy’. The Guardian (27 July, 2009) [Online.] http://www.guardian.co.uk/stage/2009/jul/27/comedy-standup-new-offenders Malik, Sarita, 2002: Representing Black Britain: A History of Black and Asian Images on British Television. London: SAGE Oliver, John, 2003: ‘Johnny Speight’ (biography). ScreenOnline. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/465520/ For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|