|

|

Lymelife

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th August 2010). |

|

The Film

Lymelife (Derick Martini, 2008)

Written and directed by first-time director Derick Martini, Lymelife offers a representation of American small town life. The film is focalised through fifteen year old Scott (Rory Culkin), the youngest son of the Bartlett family, who live in the small, affluent community of Syosset, Long Island. Scott's chauvinistic father Mickey Bartlett (Alec Baldwin) is the owner of real estate company The Bartlett Group; Scott’s highly-strung mother Brenda (Jill Hennessy) is a city girl at heart, and she yearns to return to her former home in the borough of Queens. Whilst struggling to relate to his parents, neither of whom he resembles in character, the quiet Scott is besotted with local girl Adrianna Bragg (Emma Roberts). Adrianna’s father Charlie (Timothy Hutton) is suffering from Lyme disease, and Charlie’s inability to work has necessitated his wife Melissa (Cynthia Nixon) taking the role of the ‘breadwinner’ of the family. However, whilst working for Mickey Bartlett’s company, Melissa begins an affair with Mickey. Meanwhile, Scott’s older brother Jim (Kieran Culkin), who has left home to join the military, returns home for Brenda’s birthday. Jim is aware of Mickey’s unfaithful nature, but Scott is unaware of it; and the secrets that Mickey and Melissa have been hiding from their spouses inevitable rise to the surface.

A characteristically ‘indie’ (read: quirky) little picture, Lymelife offers a variation on the now-classic ‘indie’ theme: a view of a dysfunctional family, seen through the eyes of an adolescent. The juxtaposition of the middle class Bartlett and Bragg families’ troubles, and the film’s web of pop culture references (including Scott’s obsession with Star Wars), has invited comparisons with the similarly-structured films American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999), The Ice Storm (Ang Lee, 1997) (for example, see Bradshaw, 2010) and Igby Goes Down (Burr Steers, 2002). This thematic territory has been popular within American independent cinema since the reawakening of the independent film scene in the early 1990s: for example, Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael (Jim Abrahams, 1990), also recently released on DVD by Network.

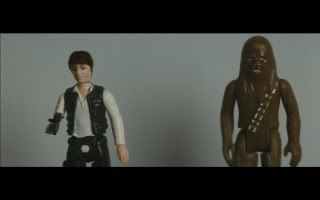

The opening sequence of Lymelife cuts between Scott and his Star Wars toys, establishing the temporal setting of the film (1979) but also drawing visual parallels between Scott and his inanimate toys – something which recurs throughout the film. In later sequences (including the film’s opening titles sequence), shots of Mickey’s architectural model of the development his company is working on, are intercut with shots of the town in which the characters live; and shots of the figures in the model are intercut with shots of the various family members. These visual parallels between the world of toys and models and the lives of the characters in the film seems to function as a metaphor for the static nature of the small town lives led by the Bartletts and the Braggs, which Brenda in particular feels constrained by – and which Jim has tried to escape. The close ups of toys, which placed in juxtaposition with the lives of the film’s characters seem to suggest a form of animism (almost as if the miniature people in Mickey’s architectural model are living their own narrative on the periphery of that depicted in the film), gives the film an element of magic realism comparable to other contemporary magic realism-tinged dramas about dysfunctional families and small communities, including the Alan Ball-scripted American Beauty, Twin Peaks (Lynch/Frost Productions, Propaganda Films, Spelling Television, 1990-1), the short-lived series John From Cincinnatti (HBO, 2007) and Alan Ball’s series Six Feet Under (HBO, 2001-2005).

There is evidence of executive producer Martin Scorsese’s authorial stamp on the film too: at several points in the narrative, Scott talks to himself in a full-length mirror in his bedroom, practising his ‘chat up lines’ in the hope of eventually impressing Adrianna, the object of his unrequited love. The framing of these shots (and the elliptical use of jump cuts to condense the time Scott spends in front of the mirror) recalls Travis Bickle’s (Robert De Niro) iconic ‘You takin’ to me?’ scene in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). Later, this recurring allusion is foregrounded when the Star Wars-obsessed Scott practises his quick draw in front of the same mirror, with a toy laser gun and a cardboard standee representation of Star Wars’ Han Solo (Harrison Ford) behind him. Elsewhere, at a social gathering, Scott approaches Adrianna, and the sequence makes us of the ‘postmodern scoring’ that has been a defining characteristic of Scorsese’s work from Mean Streets (1973) onwards: the source music begins in the non-diegetic realm, but as Scott and Adrianna come together the music moves into the diegetic sphere. In another Scorsese-inspired touch, Scott’s desiring gaze at Adrianna is depicted via fragmented, drifting close-ups of her eyes and lips – much like Travis’ gaze at Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) in Taxi Driver and Jake LaMotta’s (Robert De Niro) gaze at Vickie (Cathy Moriarty) in Raging Bull (Scorsese, 1980). For the young people in this film, escape from their daily existence seems an imperative: where Scott has retreated into a fantasy world – his understanding of his father’s business framed through his fascination with Star Wars (when Mickey shows his family an architectural model of what will be their new home, Scott declares that it looks like the Millennium Falcon; ‘You meant the Millennium Falcon in a good way?’, Mickey asks, apparently confounded by this bizarre parallel) and his lack of awareness of Mickey’s philandering ways seeming to be a case of wilful ignorance – Jimmy has escaped by joining the military. Midway through the film, Jim reveals to Scott that he left home to join the army solely because of Mickey’s philandering; Jim advises Scott to ‘go to college, in another state’. Meanwhile, Mickey disapproves of Jim’s choices, hubristically telling his sons ‘By this time next year, we will be millionaires’ before telling Jim, ‘Are you gonna quit that army shit? Make some real dough?’ However, Mickey is also beset by self-doubt, as his uncharacteristically sympathetic monologue to Scott suggests: ‘It’s tough to be a man, Scott. You’ve got to make money to put food on the table, you’ve got to be a father to your kids, you’ve got to be a husband to your wife. The money part, I’ve got; the dad part, I’m batting five hundred; the husband part… Let other people come into the picture at the right or wrong time, and things happen. I was unhappy. I am unhappy. But I promise you that everything is going to be okay’. Coming after Scott has confronted Mickey about his affair with Melissa, Mickey’s reflective monologue shows Mickey to be more than the chauvinistic philanderer that, until that point in the narrative, he has appeared to be; this aspect of Mickey is conveyed well through Baldwin’s strong performance, which shows hints of vulnerability beneath Mickey’s blusterful surface behaviour.

In fact, although the synopsis may suggest that Lymelife is a somewhat clichéd ‘indie’ picture, revisiting a well-trod set of themes, the performances in the film are uniformly strong, and thanks to the actors the characters are three-dimensional and sympathetic. Running time: 90:44 mins (PAL)

Video

The film is presented in its original screen ratio of 2.35:1 (with anamorphic enhancement). The transfer is consistently good.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel surround mix, which offers a rich, effective soundscape. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes: The film’s theatrical trailer, which places emphasis on quotes praising the film (especially Variety’s review, which described Lymelife as ‘a leaner and meaner American Beauty); An image gallery (0:28) of stills from the film; An interview with Emma Roberts (5:18), in which she discusses how she was cast, her character in the film and the experience of shooting the picture.

Overall

thematic territory that has formed the basis for so many independent films over the last two decades. However, the characters are ‘fresh’ enough that the viewer is never overwhelmed by the sense of déjà vu that a simply synopsis of the film’s plot might suggest. The film also benefits from consistently strong performances, particularly from Baldwin, Hutton and Hennessy, and a very slick visual style. (That said, the visual allusions to other pictures, especially the borrowings from Scorsese’s body of work, do at times threaten to become wearisome and could distract the viewer from the drama in the narrative.) The US DVD contains a commentary and a number of deleted scenes, plus an alternate ending; this release contains an image gallery and an apparently exclusive interview with Emma Roberts. References Bradshaw, Peter, 2010: ‘Lymelife’ (review). The Guardian (1 July 2010): en For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|