|

|

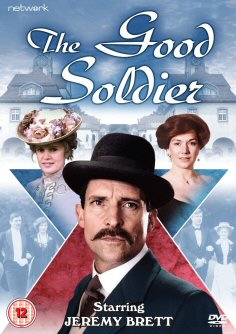

Good Soldier (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th August 2011). |

|

The Film

The Good Soldier (Granada, 1981)

This 1981 drama, adapted from Ford Madox Ford’s 1915 novel of the same title, is set in the years just prior to the First World War. It opens with an American, John Dowell (Robin Ellis), at the graveside of his former friend, Captain Edward Ashburnham (Jeremy Brett). As in Ford Madox Ford’s novel, in this film adaptation Dowell narrates the story from Ashburnham’s graveside, and aside from two framing scenes at the beginning and end of the film, the narrative is presented as an extended non-linear flashback. Standing by Ashburnham’s grave, Dowell tells us, ‘This is the saddest story I have ever heard. I can’t believe he’s gone. I can’t believe that that long, tranquil life [….] vanished’. He reflects on the early days of his friendship with Ashburnham, who Dowell met at the spa in Nauheim, Germany, where both Ashburnham and Dowell’s wife, Florence (Vickery Turner), had been ordered to retire by their respective doctors due to suffering from similar heart problems. For nine years, Dowell reflects, the Ashburnhams and the Dowells would meet once a year at the spa, and under his narration we are presented with an idyllic montage depicting Dowell and Florence, and Ashburnham and his wife Leonora (Susan Fleetwood), enjoying their stay at Nauheim. However, at the end of the sequence the tone of Dowell’s narration changes dramatically, and he asserts, ‘No. By God, that was false. It wasn’t a minuet: it was a prison, a prison full of screaming hysterics’; with this, the montage changes tone and becomes not a series of idyllic images of the rural retreat but instead a sequence of fragmented scenes depicting violence and aggression. It’s a prolepsis of some of the darker moments to be found later in the drama and establishes the tension between Dowell’s idealised vision of his long friendship with Ashburnham and the darker aspects of their relationship, and the hypocrisy and repression exposed by the narrative.

The spa and hotel at Nauheim is the setting for most of the film. It’s an idyllic setting, symbolic of wealth and luxury; Dowell tells us that he has ‘forgotten many things [….] but not Nauheim, not our hotel’, and he describes Ashburnham as ‘such a splendid fellow […] an upright, honest, fair-dealing […] character. I liked him so much; so infinitely much’. During their first meeting, Ashburnham and Florence connect immediately; Florence tells Ashburnham that she ‘should like to live in England [...] My ancestors were English’. As the narrative progresses, Ashburnham’s philandering ways are gradually revealed; Dowell discovers that Ashburnham had in the past been blackmailed by an acquaintance over the affair that Ashburnham conducted with his wife. Leonora also reveals to Dowell that she and Ashburnham did not hold a conversation for several years, since an incident in which Ashburnham had been travelling on a train with an upset servant girl and had taken advantage of her. ‘At least it cured him of philandering among the lower classes’, Leonora tells Dowell.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Dowell, Florence begins to conduct an affair with Ashburnham. Dowell becomes aware of this when Florence is found dead. ‘How does it feel to be deceived? I don’t know. It feels nothing at all. Is the proper man, the man with the right to existence, a raging stallion forever neighing after his neighbours’ women? I don’t know, and there is nothing to guide us, and if everything is so nebulous about a matter so elementary as the morals of sex, what is there to guide us in more subtle morality, or are we meant to act on impulse alone?’, Dowell wonders before asking, ‘Was I not a proper man even then?’ Dowell later discovers that Florence’s death, which he believed was due to an accidental overdose of the medication she had been given for her heart complaint, was actually a case of suicide: in fact, Florence had not been suffering from the heart complaint she claimed to have, but had fabricated the illness as a means of legitimising the Dowells’ stay in Europe, where she planned to conduct an affair with Jimmy (John Ratzenberger) but fell in love with Ashburnham. Meanwhile, Ashburnham begins a new affair with the Ashburnham’s young ward Nancy (Elizabeth Garvie), who has been put into the Ashburnham’s care. As the narrative progresses, Ashburnham’s apparent lack of ability to control his sexual impulses results in a spiral of self-destruction. A chilling and quite subversive study in hypocrisy, The Good Soldier is anchored by Dowell’s narration, which in both novel and film is potentially unreliable: frequently, as if to foreground his naivete and unreliability, Dowell expresses doubts about his ability to evaluate and understand the events he is relating to us (the phrase ‘I don’t know’ crops up repeatedly in his narration, including in his final ‘summing up’ at Ashburnham’s graveside). Throughout the narrative, a tension exists between Ashburnham’s idealised feelings for Ashburnham, who presents himself as a gentleman and is praised as a hero (‘Edward was sentimental. All good soldiers are sentimental. Their profession is full of big words: courage, loyalty, honour, constancy’, Dowell tells us as we are presented with idealised images of Ashburnham and Leonora strolling arm-in-arm) and the gradual realisation, both for Dowell and the audience, that Ashburnham is a sometimes spiteful man who seems unable to control his sexual impulses and whose philandering behaviour destroys several lives. Ashburnham is the enigma at the heart of the narrative, which is focalised through Dowell; in effect, Dowell’s function is like that of the narrator-detective in a ‘whodunnit’, as he gradually gathers evidence from the other characters (and presents it to the audience), coming to a new realisation about Ashburnham’s character. Interestingly, Ashburnham is evasive when asked by the narrator about the Distinguished Service Order he reputedly received during his time in India. ‘What is the DSO?’, Dowell asks, unaware of what the acronym stands for. ‘They give it to grocers who’ve supplied the troops, in time of war, with adulterated coffee’, Ashburnham dryly asserts.

Dowell’s reflections on the nine years during which he was betrayed by his friend and cuckolded by his wife show an ambivalence towards Florence’s infidelity: discussing Ashburnham and Florence’s affair with Leonora, Dowell is told ‘I was in hell the whole time, and you… you were happy, weren’t you, in your ignorance’. In his narration, Dowell responds to this by observing, ‘Oh, yes. They made me happy [….] For nine years I possessed a goodly apple that was rotten at the core, but only then discover its rottenness, is it not true to say that for nine years I possessed a goodly apple’. However, even at the end of the narrative, Dowell experiences no epiphany: he has not experienced enlightenment through his suffering, and reflecting on Ashburnham’s life at the graveside of his friend, Dowell intones, ‘Are all men’s lives like the lives of us good people […] broken, tumultuous, agonised and unromantic, punctuated by screams, imbecilities, agonies and death? Who knows? Perhaps society can only exist if the passionate, the headstrong and the too-truthful are condemned to suicide and madness. I don’t know. Who the devil knows? Why can’t people have what they want? The things were all there to content everybody, and yet everybody got the wrong thing. I don’t know. It’s all beyond me. It’s all a darkness’. Of course, the death of Ashburnham, a metonym for the archetypal Victorian gentleman, represents the end of an era before the tumultuous years of the Great War. The film runs for 104:50 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

Seemingly shot on 16mm film, wholly on location, The Good Soldier is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. The image is acceptable but there’s scattered evidence of damage and, from time to time, some severe fading on the right hand side of the frame. The original break bumpers are intact.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is bassy but clear. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Photo Gallery (1:01). A series of promotional stills.

Overall

Adapting Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier must have been a difficult task but, thanks to screenwriter Julian Mitchell, this television adaptation works nicely, conveying many of the techniques for which Ford Madox Ford’s work has been celebrated (his use of extended analepses, his foregrounding of unreliable narrators). The film has a difficult, elliptical narrative; particularly interesting is its use of repetition – repeating events from a different perspective – in order to cast a different light onto them. It’s a solidly-written adaptation of a notoriously difficult modernist novel, helped along by some excellent performances, especially from Jeremy Brett and Susan Fleetwood. What’s perhaps surprising is how subversive Ford Madox Ford’s expose of repression and hypocrisy amongst the Victorian gentry still seems. This adaptation is very effective. Its presentation on this release is good. For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|