|

|

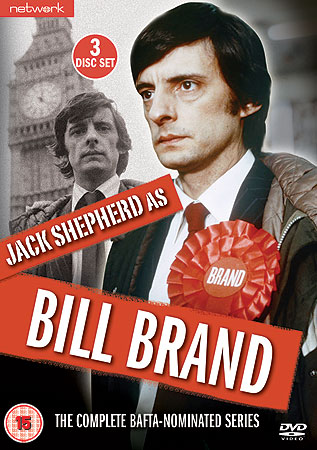

Bill Brand: The Complete Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd November 2011). |

|

The Show

Bill Brand (Thames, 1976) Created by Trevor Griffiths, Bill Brand (Thames, 1976) offered an attempt to explore the political landscape of Britain during the mid-1970s, through its narrative depicting the experiences of Bill Brand (Jack Shepherd), newly-elected Labour MP for Leighley (a fictional suburb of Manchester), in Westminster. The series has been claimed to have been rooted in an earlier Play for Today written by Griffiths, ‘All Good Men’ (BBC, 1974), which also starred Jack Shepherd and, like the later Bill Brand, dealt with the ideological conflict between one character’s (William, played by Shepherd) revolutionary ideals and the more measured views of his father, the former Labour politician Edward Waite (Bill Fraser).

As the series opens, Brand is depicted as a radical thinker. A former Trotskyite, he is from a devoutly working class background (his father is an aging chemical process worker whose work has taken its toll on his health but who refuses to retire) but has been through grammar school and teaches liberal studies at the local college – something which, in the first episode, one of Brand’s colleagues dryly refers to as ‘the opium of the working classes’. His radical left-wing views put him in conflict with the more centrist ideals of the local party leadership. The first episode ends with Brand’s triumph at the local elections, and in the second episode he is shipped off to the House of Commons where he finds his idealistic values in conflict with the beliefs of the party, who don’t want Brand’s radical socialist views to rock the proverbial boat. This is expressed bluntly by Brand’s regional whip, the ex-docker Paxton (Frank Mills), who warns Brand that ‘No government can function efficiently without information and management: ie, discipline. We expect your co-operation. These are perilous times. Your narrow win at the polls was a clear enough indication of that. One tilt, one shift, one foot in the wrong place and we’re all in the mire: government, party, country. We’re on the white lines. The government has a right to your loyalty: total, unquestioned if necessary’. When Brand reveals that he previously taught liberal studies in a college, Paxton says, ‘Figures. I was going to say if you ever worked in industry, you’d understand me’. In Westminster, Brand also discovers the extent to which politics is driven by cliques and infighting; his refusal to toe the line and learn the value of compromise leads to an antagonistic relationship with the party’s ‘journal group’. Meanwhile, Brand has to deal with the dissolution of his marriage to his wife Miriam (Lynn Farleigh), and the impact of this upon his two children. Bill Brand was intended to mirror the political circumstances at the time of its production, with the Labour government depicted in the series reflecting Harold Wilson’s Labour government that had been elected in 1974. Griffiths had joined the Labour Party in 1964 but became disillusioned with it, allowing his membership to expire in 1965 and seeking instead a career as a writer. His experience, however brief, of the inner workings of a political party shine through in this series, as does his disillusionment with Harold Wilson’s Labour Party. During this period, the Labour Party was split ‘between a moderate-right revisionist wing and an increasingly radical left-wing membership (with links to Trotskyite and trade union radicalism)’, and this conflict between more radical elements within the party and the more moderate centrist allegiances of its leadership forms the core of Bill Brand (Garner, 1999: 122). However, its examination of the conflicts that existed within the Labour party during the 1970s – between those committed to traditional socialist ideals and those seeking a newer, more media-friendly brand of leftist politics – could also be taken as prescient of the appearance of ‘New Labour’, and Tony Blair’s ‘third way’ politics, during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Griffiths had strong creative control over the series: due to his ‘clout’ as a writer, the full series was commissioned by an independent producer, and Griffiths has reflected that the ‘best provisional strategy I’ve come up with is finding an independent producer who will commission the whole lot, and give me, as it were, executive producer control over casting and directors and designers, and sell it to a company who will then find it very difficult to intervene in “ongoing artistic process”. That’s what happened with Bill Brand and insofar as that’s succeeded in achieving anything, it was because of that’ (Griffiths, quoted in 308). An advantage of the serial format, as opposed to the single play format in which Griffiths wrote Bill Brand’s precursor ‘All Good Men’, was that ‘the thirteen episodes and the serial narrative structure gave Griffiths the space to incorporate extensive political discussion and long monologues, mostly from Brand’ (Moore-Gilbert, 1994: 183). Describing himself in episode one as ‘a socialist, of the kind that [some] may describe as reactionary’, Brand is a firebrand who challenges conventional wisdom. In one episode, during a discussion of anti-terrorism legislation, Brand criticises the bureaucratic mechanisms by which more socially acceptable forms of terrorism are allowed to flourish: ‘When honourable gentlemen on both sides of the aisle talk about these “men of blood”, let them consider all the men of blood, not just those who murder with bombs and guns [….] Currency speculators, for example, who murder by telephone [….] Old people will die this winter – thousands of them, by hypothermia – as a direct result of these telephone calls. Let us have laws against capitalists and the employers who have engineered the largest investment strike over the past few years as a means of clubbing a socialist government into accepting capitalist policies. These men kill facelessly, with pen and ink, with telephones and telex machines, but they are men of blood nonetheless’ (episode 7). He is committed to social change, although from the outset he is cynical of Britain’s political institutions, suggesting that the House of Commons is like a ‘club of fleas [….] sucking our democratic lifeblood’.

Bill Brand was criticised by playwright (and Z Cars writer) John McGrath for its lack of focus and the ways in which, for McGrath, the personal story of Brand’s relationships with his wife and lover drew the audience’s attention away from the political debates uncovered by the series: ‘he [McGrath] felt [it] had become blurred and defocused by the use of the naturalist idiom’ (Franklin, 2005: 108). McGrath asserted that ‘the naturalism of the form did not allow the author to distinguish between Brand’s politics and his personal life, or to make his attitude to either all clear’ (McGrath, quoted in DiCenzo, 1996: 43). Others have seen it differently: Ridgeman argues that ‘Brand’s subjectivity […] depends on a governing relationship between his political trajectory and his domestic and sexual problems’ (2000: 84). Reminding the reader that Brand’s departure for the House of Commons coincides with the breakdown of his marriage, Ridgeman asserts that this implies ‘that his intellectual and ideological development has been at the cost of emotional detachment from his less politicised wife’ (ibid.). For Ridgeman, Brand’s burgeoning relationship with his younger mistress ‘mirrors Brand’s initiation into the more radical, extra-parliamentary activities to which she is committed, their bed becoming the site not only of sexual activity but also of ideological discussion and contemplation’, and Brand’s increasing awareness of the political compromises he may be forced to make ‘is expressed in terms of his own sexual impotence’ (ibid.). Similarly, Moore-Gilbert claims that the series’ focus on Brand’s deteriorating relationship with his wife also allowed Griffiths to explore ‘gender politics and the relation of personal and political. Unlike some other political dramas both before and after, the series tried not to compartmentalize. It traced the ways in which Brand’s personal life had implications for his political trajectory and vice versa’ (Moore-Gilbert, 1994: 183). This interweaving of the personal and political is foregrounded from the first episode, in which Miriam accuses Brand of treating a disagreement as if it were a political conference.

Nevertheless, Moore-Gilbert hypothesises that the series’ moderate success with audiences may have been largely due to ‘the personal drama of Brand rather than the underlying debate between reformism and revolution within socialist political debate’, and that ‘the drama may have been too successful at borrowing elements of soap opera, in effect giving the audience a way of avoiding the implications of political-theoretical discourse the drama contained’ (ibid.). Likewise, Jim McGuigan claimed that the series represented a ‘curious anomaly of an oppositional message encoded in a dominant aesthetic language, naturalism. Griffiths criticizes government in Britain in a way that questions the foundations of parliamentary democracy. Yet, particularly because of the overwhelming emphasis on a single individual’s experience … a possible audience response is to sympathize with Brand’s personal problems and regard him as just another individual in a difficult situation … Brecht long ago pointed to the dangerous mesh of empathy’ (McGuigan, quoted in Tulloch, 1990: 116).

Disc One: 1. ‘In’ (51:38) 2. ‘You Wanna Be a Hero. Get Yourself a White Horse’ (51:47) 3. ‘Yarn’ (51:16) Disc Two: 4. ‘Now and in England’ (51:32) 5. ‘August for the Party’ (51:29) 6. ‘Resolution’ (51:49) 7. ‘Tranquility of the Realm’ (52:37) Disc Three: 8. ‘Rabbles’ (52:15) 9. ‘Anybody’s’ (52:47) 10. ‘Revisions’ (51:59) 11. ‘It’s the People Who Create’ (52:55)

Video

Apparently shot on a mixture of videotape (for studio scenes) and 16mm film (for location footage), Bill Brand is here presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. The episodes look very good, with little damage evident throughout them. The original break bumpers are intact.

Audio

Audio is presented via a clean two-channel mono track. This is free from any issues and is always audible. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Sadly, there is no contextual material.

Overall

A truly superb series, Bill Brand is very much of-its-time but nevertheless deals with issues that are still relevant today. It never patronises its audience, and features consistently strong writing and some great performances. Criticisms have been levelled against the series’ mixture of politics and domestic drama, but as noted above these two elements of the series could be said to mesh nicely, exploring the relationships that exist between the personal and the political. The relationships between the characters are keenly-observed – in particular, the relationship between Brand and his ailing father. Griffiths’ experience of the ‘inner workings’ of Britain’s political system and, particularly, the Labour Party shines through the series and makes viewing it a rich and enlightening experience. This DVD release contains a very good presentation of the series. The episodes are in remarkably good shape. The only downside is the lack of any contextual material. Nevertheless, regardless of this, it’s a pleasure to have the series available on a home video format. References DiCenzo, Maria, 1996: The Politics of Alternative Theatre in Britain, 1968-1990. Cambridge University Press Franklin, Bob, 2005: Television Policy: The MacTaggart Lectures. Edinburgh University Press Garner, Stanton B, 1999: Trevor Griffiths: Politics, Drama, History. University of Michigan Press Hare, David et al, 1982: ‘After Fanshen: a discussion’. Bradby, David et al, 1982: Performance and Politics in Popular Drama: Aspects of Popular Entertainment in Theatre, Film and Television, 1800-1976. Cambridge University Press: 297-314 Moore-Gilbert, B J, 1994: The Arts in the 1970s: Cultural Closure? London: Routledge Ridgeman, Jeremy, 2000: ‘Patriarchal Politics: Our Friends in the North and the Crisis of Masculinity’. In: Llewellyn-Jones, Margaret (ed), 2000: Frames and Fictions on Television: The Politics of Identity Within Drama. London: Intellect Books: 74-98 Tulloch, John, 1990: Television Drama: Agency, Audience and Myth. London: Routledge Tulloch, John, 2006: Trevor Griffiths. Manchester University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network. This release has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|