|

|

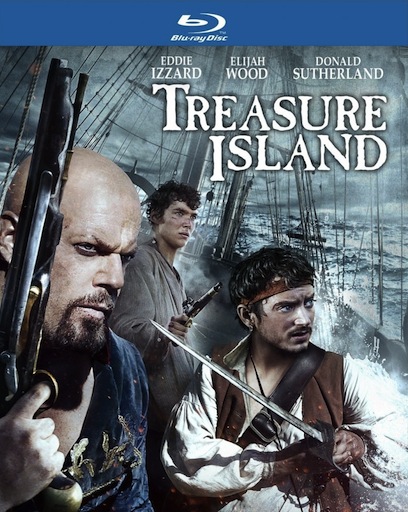

Treasure Island

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray A - America - Gaiam Vivendi Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Ethan Stevenson (17th September 2012). |

|

The Film

The pirate with one leg, the talking parrot, the treasure map where "X" literally marks the spot—just a few of the now-ubiquitous things thought up by author Robert Louis Stevenson (no relation, I’m afraid) in his much-beloved swashbuckling buccaneers meets coming-of-age tale “Treasure Island”. The novel’s impact on our culture, particularly in how we imagine pirates and the era they inhabited, is immense. So much so, if anyone makes a maritime adventure set in the era, no matter the medium, chances are they’re referencing Stevenson’s work in some way, consciously or otherwise. Often (in fact, more often than not, it seems) most don’t even bother to buck the formula, or try and think up original ideas set in pirate-y times. They’d rather just adapt the book. Remake it and shape it in their own way, sure—reconfigure the iconic characters, reference elements of the well-known plot while also crafting their own story… perhaps even take it completely out of the Caribbean sea, updating it into a futuristic time and setting in outer space (as Disney did with the somewhat underrated “Treasure Planet” (2002)), or put a comedic musical spin on it and throw in some Muppets (“Muppet Treasure Island” (1995) is my favorite version, but not because it’s faithful to the source; it’s my favorite because… well, because, Muppets. And I don’t need to explain any more than I already have, do I?) But, changes and all, each version is almost always “Treasure Island” in spirit. With over 50 radio programs, television shows and films bearing its name (in some form), “Treasure Island” is among the most frequently adapted works ever, and has featured prominently over the years in all three entertainment mediums at a consistent pace. The earliest feature-length filmed version of the story—a 6 reel silent, produced by the Fox Film Corporation, now lost to time—dates back to 1918, although according to record, the very first time the story was put in front of cameras was the Vitagraph-produced short film “The Story of Treasure Island” (1908). Orson Welles famously produced an adaptation for his The Mercury Theater on the Air radio hour in 1938 only a few months before broadcasting his notorious take on H.G. Wells “War of the Worlds”. Welles also appeared in the internationally produced film “Treasure Island” (1972), where he played Long John Silver. And, of course, The Walt Disney Company took their first stab at the story, long before the animated space adventure update, when they produced one of the most well known takes on the tale in “Treasure Island” (1950), starring Bobby Driscoll and Robert Newton. The adaptation was one of the company’s first forays into live action (it was the their first film to not feature any animation, although the infamous “Song of the South” (1946), which mixed both live action and animation, of course came before it). Stevenson’s story has featured most predominately in television, perhaps in part because of the sprawling nature of his well-crafted narrative, the first such ventures was “The Adventures of Long John Silver” (1954), a 26-episode Technicolor series shot in Australia, broadcast on early American and British network TV, in which Newton reprised his role as Silver. Over the years, several small screen adaptations have been produced, from the mostly faithful—like Fraser Clarke Heston’s “Treasure Island”, starring Charlton Heston as Silver and a youthful Christian Bale as the young Jim Hawkins, which often quoted verbatim from Stevenson’s pages—to others decidedly more literarily loose. This new two part, three-hour, version reviewed—directed by Steve Barron and written by Stewart Harcourt—is of the noticeably looser variety (although, like “Treasure Planet”, it still retains the spirit, if not exactly every element of the original fictional work). It’s much looser, in fact; to the point where the miniseries might be easier to digest for some diehard fans as something other than Stevenson’s “Treasure Island”—a side-quel to the modern “Pirates of the Caribbean” (2003-2011) movies, which owe quite a lot to the originator of most pirate tropes, perhaps. Those looking for a dutifully faithful adaptation of the novel, particularly those who will accept total adherence to the source and nothing else, ought to look elsewhere. Or at least reframe their mindset to think that this isn’t based on Stevenson’s work. Barron’s miniseries takes many liberties with the “Treasure Island” material, reinterpreting characters, adding in considerable back-story and side plots, and even makes a few casting decisions that somewhat neuter the tale of its more potent questions of morality and the corruptibility of youth. However, if you’re willing to permit the looseness, you might find this “Treasure” pleasurable. It’s certainly fun and adventurous, and surprisingly well produced for a television miniseries. And, although this probably means little in the era of Megasharks, Giant Octopi, and the inevitable horrible hybrid of the two (oh, wait, that happened), “Treasure Island” is easily one the best new things SyFy—who aired the series in the US in two parts, on consecutive nights—has had on their airwaves in a few years. (Note: the series was produced by British Sky Broadcasting and RHI Entertainment, and was merely broadcast on the SyFy network). The story, as is expected, is concerned with young Jim Hawkins (played Toby Regbo, a boy-faced 22 year old not quite right for the part, at least in terms of looks), the son of poor English innkeepers. With his father recently deceased, the inn in danger of falling into the hands of others in the likelihood that his mother (Shirley Henderson) will default on his father’s unpaid debts, and a map soon falling into young Master Hawkins’ hands by way of luck, the boy joins a voyage aboard the “Hispaniola”, a schooner charted to the Caribbean in search of a certain Captain Flint’s famed buried treasure. Paying the way is Squire Trelawney (Rupert Penry-Jones), the nobleman to which Jim’s parents owed a great deal of money. Captaining the ship is a self-righteous man named Smollett (Philip Glenister). Along for the trip is the docile Doctor Livesey (Daniel Mays), a good friend of Jim’s parents. And by pure chance—or so he makes it appear—a crafty man with one leg, named Long John Silver (Eddie Izzard), works his way onto the “Hispaniola” as the cook, and convinces the good captain and Trelawney to crew the ship with unseemly men chosen by the most-seaworthy Silver (many of whom, unbeknownst to all but Silver himself and these select men, were part of the famous Flint’s gang). The miniseries is divided into two 90-minute movies—each with their own set of credits—on this Blu-ray, and is comprised of, essentially, six acts. Or, a prologue and five acts to be more precise. Much like a novel. The prologue, in which a misused Donald Sutherland appears as Flint, provides considerable back-story not explicitly detailed in Stevenson’s narrative, and the filmmakers take liberty in giving the audience this information. We learn how Long John lost his leg—here, he was shot point blank in the leg by the crazed captain, shattering the knee and necessitating amputation—as well as what happened to the old crew, and, most importantly, to Flint’s treasure, in exacting detail. The first half of the mini focuses a considerable amount of time on setting the scene; it isn’t until nearly 40 minutes into the first part that the “Hispaniola” and her crew set sail for the tropical Isles, and even then much of rest spent aboard ship is a slow-burn game of wait-n-see, until Silver and his men spring the trap of mutiny upon Smollett and Trelawney, right as they reach the island. The second half is nearly all conflict and combative action, with a race to find the treasure, and young Jim caught between loyalty to the crown (and Smollett, Trelawney, and yes, the good doctor) and loyalty to his newfound friend, Silver, who befriended the outcast cabin boy aboard the “Hispaniola” when all others discounted him. Interwoven between the two parts are constant, entirely new, asides, flashing to Jim’s mother back in England, in which she worries and unknowingly takes up with Silver’s wife (Nina Sosanya), who’s hiding from Black Dog, one of Flint’s old crew on the lookout for Long John’s piece of the old treasure. Both women play their parts well, although at times the subplot seems an obvious and unneeded foil to the plight of the “Hispaniola” crew (as Jim learns he’s been cut out of the treasure by Trelawney, we see back in England one of the nobleman’s henchmen throw Mrs. Hawkins and Mrs. Silver out of the inn, onto the rain soaked streets). Double crosses and questionable ethical ambiguity, it’s all there—and genuinely thrilling and compelling too. As are, of course, the basics of the “Treasure Island” story. But this reinterpretation modernizes where it need not, both in the visual sense (Barron and his cinematographer make some rather distracting decisions in terms of stylization) and in character interpretations, making it imperfect. Some of the different characterizations are ill-advised, but rather harmless, like a Yankee version of Ben Gunn (Elijah Wood), the youngest of Flint’s original crew, who’s been left out in the sun too long, his brain boiled in the 3 years he was marooned on the island to the point that he’s obsessed with cheese and obscure bible scripture, and walks around looking like a well… sort of like Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow-gone-native in “Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest” (2006), although I suppose that borrows from the original “Treasure Island”, so this miniseries version is like a copy of a copy of the original. Wood’s look is not the problem, per se, and for the most part, the actor is brilliantly bonkers as Ben. But, the decision to make Gunn a Yankee is misguided, simply because Wood’s unconvincing drawl is a distraction. Honestly, his twee Frodo accent would’ve worked better. Other character interpretations work well, from Izzard’s exceptionally likeable but equally evil take on Silver, to Penry-Jones’ more dastardly, bastardly and outright stupidly awful money-mongering take on Trelawney. Is his take different than what is described in the book? Undoubtedly. But the clear-defined villain is well portrayed in the context of this adaptation. Performances of the less commendable variety are but a few—namely one. May’s embodiment of Livesey, who is initially cowardly in this version, but becomes a powerful warrior (in contrast to the book, in which he’s consistently brave), is problematic. The coward part, May’s sells; it’s the moments when the doctor takes up arms and scares off a band of bloodied pirates that don’t work. And, now a word on Toby Regbo as Jim Hawkins. The smooth-cheeked actor, with the light curls atop his head, might convincingly play a seventeen year old, perhaps even a year younger. 13? Not believable at the age, at all. And that poses somewhat of a problem. (Not that Regbo doesn’t play his version of Jim well; he is, in fact, quite good). At the very core of "Treasure Island" is a struggle with morality, and in particular how that struggle impacts a young boy’s transition from adolescence into adulthood. There’s something chilling about a boy just entering teen-hood killing a man—even in self-defense—and that something isn’t nearly as potent when the death is at the hands of someone even a few years older (perhaps, because, at 17, one’s moral compass is better able to distinguish between right and wrong, justice and injustice, and that not everything is always black-or-white; that there are shades of grey in this world). But, in the context of this more modern-minded adaptation, and in light of a slight shift in the occurrence of adulthood in our day (which is considerably closer to 17 than the 13 of Stevenson’s era), Regbo’s version of Jim is agreeable. His more mature features and presence rob the material of some of its meatiness, and I still don’t understand why the filmmakers didn’t just cast a true teen as so many other adaptations have, but, what’s done is done; and, truthfully, done well. As a strict adaptation of the source material, Barron’s “Treasure Island” is not quite right, and the more scholarly literary types in the audience will probably find much to complain about. Character interpretations are all wrong, needless additional back-story not present in the novel has been added to expand the scope of an already epic work, and even in wide swaths, this version misses the mark in some regards. Still, I’d be lying if I said Barron’s version wasn’t entertaining, that the acting and casting choices weren’t at least interesting (and in some ways, quite acceptable), and that, as a whole, it didn’t somehow work. This version of “Treasure Island” is good fun. It’s just not the usual “Treasure Island”, exactly. But that’s okay. Then again, my favorite version of Stevenson’s story has Muppets in it, so take my review with a word of warning…

Video

In the era of the digital domain, directors and cinematographers have tools that give them total and complete control over the look of their projects. The so-called creative-minds are now able to do, basically, whatever they want within this digital realm. CG makes beasties, both beautiful and grotesque, come alive like never before. And in a more general sense, the basic computer tools used to edit and master projects allow for an-almost insane level of color and other visual manipulation. Of course, filmmakers have always had many of these tools in their toolkit, if obviously not always via computer. The ability to manipulate color—as a means to elicit a certain response from the audience, or to evoke a certain atmosphere—has been around since almost the first silent films, which employed tints (and hand-painted frames) to get the desired “look”. Other things have almost-always been achievable in camera, too. From the near-mundanely photographic: adjustments in focus and depth of field, and the basics of manipulation of lighting. To the more magical elements of the medium: over and under cranking the camera to manipulate the speed at which action unfolds, and double exposure, both of which can create ethereal effects. Different filmstocks, lens choices, printing processes, and the like have been developed over the years, and employed with great effectiveness for nearly as long, as a means to present a unique look. But in the era of digital, filmmakers have an even greater ability to manipulate their images, especially in terms of color and contrast, and in other areas too. In a way, this has given rise to more visually interesting films; ones that probably could never have existed as they now do, in anther time. “O Brother, Where Art Thou” (2000), the first ever feature-length film completely, 100-percent, finished on a digital intermediate—in which Roger Deakins and Joel and Ethan Coen took a sepia-toned, dusty dust-bowl aesthetic achieved through photographic means, and enhanced it to even greater effect via computers—simply wouldn’t have worked, at least worked as well, in the pre-digital era. But, what was once new, and visually surprising, really isn’t anymore. The rise—and proliferation—of the digital intermediate, and the non-linear editing suite, has fundamentally changed the look of film and TV. Before the DI-era, things like the garish “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” (2000-present)—with its overly punchy and, in my opinion, sickly-hued, colors and aggressive contrast, and chaotic editing—probably wouldn’t have appeared on broadcast television. At least, not with any regularity. But now, everything is “cut” on computer, and nearly every show employs all sorts of filtering and color correction, even if few go to the extremes of some of the originators. In features, the effect is even more prevalent, to the point where a film with natural colors is a rarity, and an absence of in your face editing flourishes are equally few-and-far-between. In the 12 years since “O Brother, Where Art Thou”, I’ve almost grown accustomed to all the filters and other visual manipulations prevalent in most productions. The unnatural appearance of most modern television series and films seems, well… totally natural to me. Still, I think director Steve Barron and cinematographer Ulf Brantås may have gone a bit far in trying to make this miniseries more visually interesting than it really need be (in part because it’s already quite a pretty picture simply because of the sets, costumes and locations, without the extra touches). They’ve combined the old and the new in a most troubling way. Colors filters are employed in an obvious and almost comically extreme way. The early scenes in England are tinted an, I suppose, depressing blue-gray, the effect of the seemingly candle and oil-lamp lit night scenes exacerbated by a bathing of brownish sepia, the daytime scenes aboard ship are at times a lighter blue-white (perhaps the most natural) and at others the dreaded teal-and-orange, and the scenes on the island are tinted somewhat yellow-green. Barron, Brantås and editor Alex Mackie’s stylistic flourishes are varied, but almost universally annoying. Action scenes sometimes play out in quick, jarring, under-cranked madness, like something out of “The Benny Hill Show” (1969-1989). Worse are the moments when the undercranking appears in dull moments—something as mundane as Jim giving Silver a haircut has at least two jumpy under-cranks. Odd camera pans, erratic alternations between handheld and steady, presumably track-based, camerawork, and tiny wholly unnecessary zooms are bothersome and distracting. Most noticeably, and of some detriment to the presentation on the blu–ray, is the fact that the camera crew is all over the place in terms of focus. Wide shots are consistently sharp. But in many of the tight close ups, only part of the object in frame is in sharp focus, with an exceedingly shallow depth of field shrouding everything else in indistinct ambiguity. Many other scenes showcase slight blurriness on the edges. And sometimes scenes even weaver between the two states on purpose. Worst of all are the numerous, moody, mist-filled scenes in part one, which appear to have had the mist added (or artificially enhanced) via CGI. Not only does it look completely unconvincing, but also the effect pulls all sense of depth out of the picture, leaving the appearance of a dull gray, contrast-less, nothingness. This means my job in scoring the generally good-looking disc is harder than it ought to be. On one hand, the 1.78:1 widescreen 1080p 24/fps VC-1 encoded transfer appears utterly faithful to the style and intentions of the filmmakers. It has a strong black level, there are seemingly endless amount of rich textures on display, and many other niceties, all of which translate well to Blu-ray. On the other, the disc is not just inconsistent in terms of color reproduction, contrast, detail, and other areas, but often erratically so, if in service and as a result of the cinematography. Technically, the encode is largely free of issue; shot digitally with the increasingly popular Arri Alexa, the grain-less digital photography is clean, and the resulting image shows no signs of obvious edge ringing, aliasing or other similar flaws. The three-hour series is housed on single, roomy, dual layered BD-50, and artifacts and noise is a non-issue, a few moments of brief banding during scenes featuring the poorly rendered CGI-mist excluded. I can’t say this is a bad looking production, and certainly not a problematic disc, at least for the most part. Just… with its proper period production design and costumes, and exotic locales, the series already had that “visual interest” the creative crew wanted, and a more reserved (even organically filmic) approach might have worked best for something as classic—reimagined or not—as “Treasure Island”.

Audio

Despite its cable television origins, Barron’s “Treasure Island” could easily stand among the theatrical big-boys quite well, with an impressive lossless audio track indeed. The English DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix (48kHz/24-bit) is a nice, if not persistently bombastic, one. The track has crisp dialogue, if, as always, one’s ear for accents will depend on the overall clarity of delivery. The solid surround presence features light elemental and environmental atmosphere, with crowd chatter (most pronounced in the early scenes, when Jim has left home but not set out of port), and crashing waves, creaks of the ship and other seafaring sounds often filling the rears with a believably regular irregularity. And the mix features fine fidelity and decent depth. Cannon blasts provide the lowest of the low end, and although your sub isn’t likely to get an intense work out, it’ll get use. The score by Antony Genn and Martin Slattery is lively and supports the action well. Optional English subtitles are also included.

Extras

Although impressive at first glace, “Treasure Island’s” long list of bullet points on the back cover boil down to few meaningful extras. The audio commentary is worthwhile, but the featurettes are merely serviceable and all too brief. The disc also includes a few bonus trailers, including one for the miniseries itself. The audio commentary by director Steve Barron and actor Eddie Izzard—available on both parts of the miniseries—is a decent listen. The two men are obviously passionate about the project, and keep up a light but informative tone throughout the 3-hour runtime. Pauses happen, but plenty of information about the origins of the adaptation, the script, the casting, the characters, the filming locations and just general stories from the set are shared in an easy-going fashion. They spend a considerable amount of time discussing the diversions from the source material. “The Making of ‘Treasure Island’” (1.78:1 1080p, 4 minutes 2 seconds) is a brief featurette, with Barron, Issard, executive producers Mark grenside and Alan Moloney, actors Elijah Wood, Toby Regbo and others offering insight into this loose adaptation, which someone annoyingly calls the “rock-n-roll version of ‘Treasure Island’”. That’s not even remotely accurate. The vague tab listed as “Cast Interviews” (1.78:1 1080p) hides 4 featurettes with the cast, each talking about their character and briefly discussing this new, looser, version of the famous “Treasure Island” story. The individual featurettes are: - Eddie Izzard(2 minutes 50 seconds). - Elijah Wood (3 minutes 10 seconds). - Toby Regbo (2 minutes 7 seconds). - Philip Glenister & Rupert Penry-Jones (1 minutes 59 seconds). “A Tour of the Hispaniola” (1.78:1 1080p, 2 minutes 2 seconds) is a featurette with marine coordinator Dan Malone, in which he briefly discusses the tall ship that was used in the miniseries. The absurdly brief “Anatomy of a Stunt” (1.78:1 1080p, 1 minute 4 seconds) is a featurette with stunt coordinator Manny Siverio, where he talks about a scene in the crow’s-nest. A theatrical trailer (1.78:1 1080p, 2 minutes 28 seconds) for the miniseries has been included. Pre-menu bonus trailers are included for: - “Alphas” (1.78:1 1080i, 11 seconds) on SyFy. - “Warehouse 13” (1.78:1 1080i, 11 seconds) on SyFy. - “Neverland” (1.78:1 1080p, 2 minutes 26 seconds) on blu-ray and DVD.

Packaging

“Treasure Island” comes to Blu-ray via Gaiam Vivendi Entertainment, distributing the film on home video in the US for Sky and RHI Entertainment. The 2-part, 3-hour, miniseries is housed on a single BD-50 and packaged in an Elite eco-case. A slipcover is included in first pressings. The slipcover, case art and disc art all incorrectly list DVD-region information, stating it coded for region 1, rather than the Blu-ray applicable region A.

Overall

RHI and Sky’s “Treasure Island” is but another in a long line of adaptations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic tale. And, it’s far from the most faithful. In fact, as an adaptation of the source, it is, in a more academic sense, quite questionable—certain characters are wrong, needless additional backstory not present in the novel diverts from the main plot and over explains subtext, and, even in wide swaths, this version of “Treasure Island” misses the mark in some regards to the message of the work. Still, this is actually a very fun, well-done adventure. Maybe it’s not “Treasure Island” in the true sense, and it’s probably best to think of the miniseries as something entirely different if you really, really, really love the source and won't accept anything but utterly faithful interpretation. (As another “Pirates of the Caribbean”, perhaps. In that context, this is actually better than “Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides” (2011), in my mind). The Blu-ray has a good transfer, which renders the at-times troubling visual stylization accurately, a very good lossless audio track, and a deceivingly sized selection of serviceable extras. Worth a look.

|

|||||

|