|

|

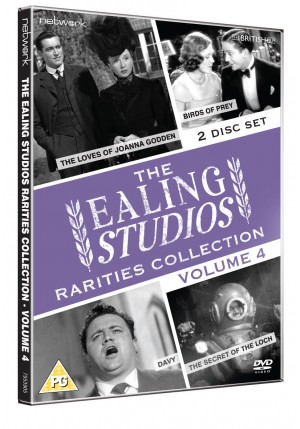

Ealing Studios Rarities Collection, Volume 4 (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th July 2013). |

|

The Film

The Ealing Studios Rarities Collection Vol 4 Contents: DISC ONE: ‘The Secret of the Loch’ (72:55) ‘The Loves of Joanna Godden’ (85:35) Stills Gallery (4:48) DISC TWO: ‘Birds of Prey’ (91:12) ‘Davy’ (79:17) The Secret of the Loch (Milton Rosmer, 1934)  The Secret of the Loch is notable as the first film to deal with the legend of the Loch Ness monster. The picture opens with a title card reading: ‘Extract from Daily Mail of Oct 19th 1933. Whether people believe in the existence of a Loch Ness “MONSTER” or not, Highlanders are convinced that the watery depths harbour some fantastic, and abnormal creature’. The Secret of the Loch is notable as the first film to deal with the legend of the Loch Ness monster. The picture opens with a title card reading: ‘Extract from Daily Mail of Oct 19th 1933. Whether people believe in the existence of a Loch Ness “MONSTER” or not, Highlanders are convinced that the watery depths harbour some fantastic, and abnormal creature’.

Various newspaper headlines appear onscreen: ‘Loch Ness Monster Reappears’, ‘Seen with Lamb in Its Mouth’, ‘People Alarmed’. A man runs through the mist. A woman closes her curtains. People look on, horrified. The man enters a pub and shouts, ‘Boys! Boys! I’ve seen it’. He tells them he saw Nessie as she ‘came through the mist. Oh, it was terrible’. The pub’s landlady, Maggie Fraser (Rosamund John), informs the men that they are like a group of ‘old women’. Another man appears, Professor Heggie (Seymour Hicks). The men in the pub tell him of the monster. Heggie shows the men the newspapers. ‘That’s what London says about us’, he says. The headline reads ‘Mass hallucination’. ‘These “clever people. They think we’re superstitious. Maybe we are. But they’ve never known the Loch as we have known it’. Cut to another meeting: a group of scientists say that they must investigate the monster, as it is of scientific interest. Amongst this group, Heggie claims that the monster is ‘a reptilian survivor of prehistoric ages, a giant dinosaur, a diplodocus’. A journalist for The Daily Sun, Jimmy Anderson (Frederick Peisley), approaches Heggie. In search of a good story, Anderson follows Heggie to Loch Ness. Visiting the pub near the loch, Anderson talks to a drunken man who claims to have seen the monster. ‘I don’t think he’s speaking the truth’, his companion says. ‘Never mind, it’ll make a great story’, Anderson says. Whilst near the loch, Anderson meets Heggie’s daughter Angela (Nancy O’Neil). He begins to fall in love with her. The stage is set for a climax in which Anderson dives deep into the loch and comes face to face with the monster (played in the film, through the magic of composite effects, by an iguana). The film seems to have been a reference point for Ken Russell: on the commentary track for the 2003 Pioneer DVD release of Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm (1988), Russell references the climax of The Secret of the Loch, in which the film’s protagonist descends into the loch and comes face to face with Nessie. Russell says that the cave in this climax ‘looked like a cracked flower pot upside-down’, and the diver resembled the ‘one I had in my bath on Friday nights’: ‘the image, ladies and gentlemen, that terrified me and today still haunts my dreams, is this image […] of a gigantic, sixty-foot plucked chicken coming round the flower pot [….] It’s an image I hope you never encounter yourselves, because it changed my life. It made me what I am today: totally mad’. The film could be said to reinforce stereotypes of drunken Scots, and in its depiction of an insular Scottish community – which would come to be a cliché of later 20th Century cinema – predates such films as Whisky Galore! (Alexander Mackendrick, 1949), The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy, 1972) and Local Hero (Bill Forsyth, 1983). David Martin-Jones has said that The Secret of the Loch emphasised ‘the union of the two nations [England and Scotland] through technology’ and underscored this by the inclusion of ‘an English-Scottish romance’ that was ‘typical of any number of British films set in Scotland’ (2009: 94). Martin-Jones says that in films of this period, ‘[v]isits to Scotland by English protagonists often represent the unity that exists between the two nations through a romantic union between the English stranger and a native Scot’: in The Secret of the Loch, the English journalist Anderson falls in love with the Scottish daughter of Heggie, Angela (ibid.). For Martin-Jones, the union of Anderson and Angela is ‘defined by their communal belonging to the British middle-classes’; Martin-Jones also notes that Angela’s ‘voice [is] devoid of any trace of a Scottish accent’ (ibid.). When the couple go for a drive in Angela’s car, ‘the middle-class Scottish woman and English man stand out against the Kailyard locals, representing the union of the British middle classes that supposedly spans the national divide’ (ibid.) The film runs for 72:55 (PAL). The Loves of Joanna Godden (Charles Frend, 1947)  Adapted from Sheila Kaye-Smith’s 1921 novel Joanna Godden, The Loves of Joanna Godden takes place on the Romney Marsh: ‘Lonely now, but lonelier still in 1905’, the opening scrawl tells us. Adapted from Sheila Kaye-Smith’s 1921 novel Joanna Godden, The Loves of Joanna Godden takes place on the Romney Marsh: ‘Lonely now, but lonelier still in 1905’, the opening scrawl tells us.

Into this environment arrives Joanna Godden (Googie Withers) and her younger sister Ellen (Jean Kent). They have traveled for the reading of their father’s will: in it, their father has left five hundred pounds to Ellen, and has bequeathed his farm to Joanna. However, a codicil states that Joanna will acquire the farm only if she becomes married. Joanna is determined to make a success of her father’s farm, despite being warned that her father ‘didn’t make a ha’penny out of it [the farm] over these past five years’. She vows to run the farm herself. ‘But the men, they won’t take orders from a woman’, she is told by her fiancé Martin (Derek Bond): ‘You sound as if you’re marrying the farm instead of me’. ‘Perhaps I am’, she says. Joanna becomes the talk of the local village. ‘There goes your strong man’, one of the men in the local pub comments dryly when he sees Joanna riding by on her horse and trap. Meanwhile, Joanna’s neighbour Arthur (John McCallum), who is falling in love with Joanna, warns her about her idea to cross-breed her father’s ‘fine pedigree flock’. Joanna becomes convinced that the farm’s future success will lie in her ability to cross-breed her sheep. She is also motivated by her desire to see her younger sister Ellen succeed in life, although Arthur also advises Joanna not to continue sending Ellen to ‘fancy new schools’ as it’s ‘one expense you can’t afford: making Ellen a lady’. Sue Harper frames The Loves of Joanna Godden amongst Ealing’s postwar films, which Harper claims were concerned with ‘creating a taxonomy of the middle-class, and with censuring profane females’ (2000: 57). As Harper notes, the film deviates substantially from its source novel, Sheila Kaye-Smith’s Joanna Godden (1921). Where Kaye-Smith’s novel was ‘the story of a woman farmer who decided not to marry the father of her child’ and ‘ended with a celebration of female independence’, Frend’s film adaptation ‘insists that the heroine (Googie Withers) is “a mare who ain’t never been properly broke in, and she wants a strong man to do it”’: she is not accepted within the ‘male domain of farming, and [she] is lonely in her single state’ (ibid.: 58). On the other hand, Brian McFarlane argues that The Loves of Joanna Godden is the ‘most explicit articulation of a feminist agenda’ within Googie Withers’ body of work as an actress (2009: 72). McFarlane suggests that, ‘helped by severe hairstyle and costumes, [Withers] compels belief in Joanna as a woman in charge, whether casting an appraising eye over sheep-dog trials or hiring a new shepherd […] with whom she talks knowledgeably about “cross-breedin’”’ (ibid.: 72-3). Margaret Butler states that the film ‘juxtaposes an unromantic pastoralism with sharp contemporaneity’, highlighting the extent to which Godden’s need to prove herself in a man’s world would have chimed with the experiences of many women in postwar society ‘who had combined paid work with running the household while their husbands were away on war service’ (2004: 71). Butler suggests that the film is subtly subversive in its attempt to defy ‘perceived notions of the rural idyll’ at a time when ‘National Parks were being planned to enable the public to see nature “raw and triumphant”’ (ibid.: 72). The film runs for 85:35 (PAL). Birds of Prey (Basil Dean, 1930)  Adapted from A A Milne’s play The Fourth Wall (1928), also known under the title The Perfect Alibi, Birds of Prey takes begins during a fete. Women sun themselves whilst the men taste wine. Over dinner that evening, a man called Laverick (Warwick Ward) arrives; late, he is expected by the people around the table. They talk of danger, and Laverick says that he was attacked by a bird during a trip to Skye. When asked if he carries ‘some sort of a gun’, he asserts that ‘it’s much safer without weapons’. Adapted from A A Milne’s play The Fourth Wall (1928), also known under the title The Perfect Alibi, Birds of Prey takes begins during a fete. Women sun themselves whilst the men taste wine. Over dinner that evening, a man called Laverick (Warwick Ward) arrives; late, he is expected by the people around the table. They talk of danger, and Laverick says that he was attacked by a bird during a trip to Skye. When asked if he carries ‘some sort of a gun’, he asserts that ‘it’s much safer without weapons’.

At the table, another man, Arthur Hilton (C Aubrey Smith), reflects on his time in Africa, where he co-ordinated the Natal Mounted Police. There, he rounded up a gang of three murderers: they almost killed him, ‘but they wouldn’t believe I was a policeman because I didn’t carry a gun’. Only one of the men was executed; the others vowed revenge. ‘Weren’t you frightened?’ a woman asks. ‘I got used to that sort of thing over there’, the man says. Laverick looks on suspiciously. Later, another of the group, Carter (Robert Loraine), confides in Hilton that he found a letter in Laverick’s jacket – when he put it on, mistakenly thinking it to be his own – which suggests that Laverick may have some association with the killers in Natal. Carter and Hilton set a trap for Laverick… Birds of Prey is a fairly interesting mystery play set amongst the upper middle classes. The narrative develops in unexpected directions, but the film doesn’t tread new ground and is quite static and ‘stagy’ – a common characteristic of Basil Dean’s work during this period; in 1930, he had only recently moved from the world of theatre into the world of cinema. The film runs for 91:12 (PAL). Davy (Michael Relph, 1958)  In many ways, Davy represents the last gasp of Ealing (the studio would produce only three more films) and, it has been suggested, the film narrativises Ealing’s relationship with Hollywood. Aesthetically, the film also represents a break with Ealing’s traditions. In an issue of Kinematograph Weekly in 1954, Ealing announced that, as a means of making its films more easily marketable in the US, its future productions would be shot in VistaVision. Plans to use the VistaVision format never came to fruition, but Davy was the first British film to be shot in the similar Technirama process. In many ways, Davy represents the last gasp of Ealing (the studio would produce only three more films) and, it has been suggested, the film narrativises Ealing’s relationship with Hollywood. Aesthetically, the film also represents a break with Ealing’s traditions. In an issue of Kinematograph Weekly in 1954, Ealing announced that, as a means of making its films more easily marketable in the US, its future productions would be shot in VistaVision. Plans to use the VistaVision format never came to fruition, but Davy was the first British film to be shot in the similar Technirama process.

Set during the dying days of the music halls, the film opens with young boys outside a music hall, sneaking a peak at the shows. They are warned off by a security guard. Meanwhile, young Tim Morgan (Peter Frampton) and his mother Gwen (Susan Shaw) arrive, looking for Tim’s father George (Ron Randell). George is in a comedy troupe, The Mad Morgans, with Pat (George Relph), Eric (Bill Owen) and Davy (Harry Secombe). George reveals that The Mad Morgans have been spotted by a scout for Val Parnell and have been offered a position at the Finsbury Park Empire which may lead to a performance at the Palladium and a television appearance. When Pat queries whether the scout wants the act or just Davy, who is shown to be the pivot around which The Mad Morgans act revolves, George says, ‘Davy is just part of the act’ and proposes changes to the act that will minimise Davy’s role within it; needless to say, the other members of The Mad Morgans resist this. However, Davy also reveals that he has been offered an audition at the Royal Opera House, to sing in front of Sir Giles Manning (Alexander Knox). George is incensed at this: ‘To the opera house. You’re going to sing at the opera house?’ ‘What do you think, to the market?’, Davy asks. George is angry that Davy will take an audition ‘just when we’re about to get our big break’: ‘You’ll just make a big fool of yourself’, George says. ‘Then it shouldn’t matter to anyone, George. It shouldn’t matter at all’, Davy says. Davy finds himself torn between his ‘family’ troupe and the world of the music hall, which is on its last legs, and the glamour and promise of a career in opera. At the end of the film, Davy decides to stay with the Mad Morgans, telling Tim ‘I think we should all stick together’. Alan Burton and Tim O’Sullivan state that through this denouement, ‘the underlying message of the film appears to be “know one’s place” and that individual talent and ambition – including the promise of romance – must be unquestioningly disciplined by loyalties and obligations to the family’ (2009: 133). When Davy is positioned between ‘the known, familiar world of the Music Hall and the elite, rarefied atmosphere of The Royal Opera House’, he ultimately settles ‘for the “old” and rejects the “new”, for the status quo, rather than change’ (ibid.). In his book on Ealing, Charles Barr notes that the film is set during the last gasp of the music hall era and compares the film with John Osborne’s 1957 play The Entertainer. For Barr, Davy ‘offers a close parallel [to The Entertainer], with its family structure and with the attempt, in the act, to spin out a nostalgic communal gaiety which can now only seem artificial and desperate’ (1998: 11-12). Barr suggests that the film is really about the state of Ealing Studios itself, ‘struggling to hold together after the move of their headquarters to Borehamwood’ (ibid.: 12). Davy’s choice between staying with his music hall family and gravitating towards the elite glitz of The Royal Opera House represents the choice several key players within Ealing (such as Alexander Mackendrick) had made between remaining with the Ealing ‘family’ or moving to Hollywood. (As Barr notes, the writer of Davy, William Rose, would make the transition to Hollywood shortly after the production of Davy.) The refusal of The Mad Morgans to change their act, and the clear downward state of the music hall tradition generally, makes Davy’s decision to remain with The Mad Morgans ‘a quixotic one’. Barr states that ‘[w]ithout imposing too facile an identification, one can surely hear [Michael] Balcon’s voice behind lines like this. He had committed Ealing to go on making films of the same type, with the same team, rather than make any adaptation to changing times and a changing industry’ (ibid.). The film runs for 79:17 (PAL).

Video

The Secret of the Loch, The Loves of Joanna Godden and Birds of Prey are monochrome productions. The former two titles are presented in their original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. Birds of Prey is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.19:1. The Secret of the Loch is in fairly good shape, although there are scratches and other evidence of light wear and tear throughout the film. The Loves of Joanna Godden demonstrates less overt damage, but as the film progresses the contrast is a little ‘off’: highlights are blown out slightly for most of the film. Nevertheless, it’s never less than watchable. Of the monochrome films, Birds of Prey has the most handsome presentation: the film is in remarkably good condition, with strong contrast levels throughout. Davy is the ‘odd one out’. Shot in Technirama, the film is presented here in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The film is in Technicolor too. Colours are sharp and strong. This is a very handsome presentation of the film, which makes interesting use of the widescreen frame during the depictions of the revue show – the players spread out across the frame, with cuts to wide shots of the audience. The Secret of the Loch:

The Loves of Joanna Godden:

Birds of Prey:

Davy:

Audio

Audio for all films is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is clear throughout, with The Secrets of the Loch demonstrating the most damage – but nothing that makes the dialogue difficult to discern. Sadly, no subtitles are included.

Extras

Extras (on disc one) include a stills gallery on disc one and a lengthy audio interview with Sidney Cole (80:47).

Overall

Volume four in Network’s Ealing Studios Rarities Collection contains an interesting, diverse selection of films from amongst the earliest in Ealing’s history (Birds of Prey) to one of the last films to be produced by the studio (Davy). The Secrets of the Loch is the most entertaining of the bunch, arguably, whilst The Loves of Joanna Godden is the most interesting; nevertheless, there is also much to enjoy in both Birds of Prey and Davy, although criticisms of the latter tend to be well-grounded: it’s very conservative in its worldview, and quite static in its narrative. There’s variance in the presentation of the films included in this set, although none of the pictures are less than watchable. Purchasers of the earlier volumes in this collection will definitely wish to buy this set too. References: Barr, Charles, 1998: Ealing Studios. University of California Press Butler, Margaret, 2004: Film and Community in Britain and France: From ‘La Règle Du Jeu’ to ‘Room at the Top’. London: I B Tauris Burton, Alan & O’Sullivan, Tim (2009): The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph. Edinburgh University Press Harper, Sue, 2000: Women in British Cinema: Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know. London: Continuum Martin-Jones, David, 2009: Scotland: Global Cinema, Genres, Modes and Identities. Edinburgh University Press McFarlane, Brian, 2009: ‘Ingenues, lovers, wives, and mothers: The 1940s career trajectories of Googie Withers and Phyllis Calvert’. In: Bell, Melanie & Williams, Melanie (eds), 2009: British Women’s Cinema. London: Taylor & Francis: 62-76 This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|