|

|

Brain Machine (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (12th November 2013). |

|

The Film

The Brain Machine (Ken Hughes, 1955)  In the book Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (2010), Andrew Spicer discusses the rise of British films noirs during the late 1940s and into the 1950s. Spicer suggests that in the 1950s, British films noirs were pretty much ‘exclusively second-feature crime films’ and featured an increasing reliance on the paradigms of American films noirs of the period, with some of the films even featuring imported American casts and crew members: notably, both Cy Endfield and Joseph Losey made crime films in Britain after they were both blacklisted by the American film industry during the McCarthy era (31). However, there were some subtle differences between American films noirs and British films that broadly conformed to the noir template or aesthetic: Spicer notes that ‘most British noirs retained an emphasis on ordinary people, not a detached underworld, and melded the pace and action of American films with the depiction of resonantly British milieux’ (ibid.: 32). Spicer argues that Ken Hughes’ films are the strongest examples of this attempt to marry the ‘pace and action’ of films noirs being produced in the US with subject matter and locations that are resolutely British. Of Hughes’ films, Spicer cites Wide Boy (1952), The House Across the Lake (1954), The Long Haul (1957) and The Brain Machine as examples of this trend. In the book Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (2010), Andrew Spicer discusses the rise of British films noirs during the late 1940s and into the 1950s. Spicer suggests that in the 1950s, British films noirs were pretty much ‘exclusively second-feature crime films’ and featured an increasing reliance on the paradigms of American films noirs of the period, with some of the films even featuring imported American casts and crew members: notably, both Cy Endfield and Joseph Losey made crime films in Britain after they were both blacklisted by the American film industry during the McCarthy era (31). However, there were some subtle differences between American films noirs and British films that broadly conformed to the noir template or aesthetic: Spicer notes that ‘most British noirs retained an emphasis on ordinary people, not a detached underworld, and melded the pace and action of American films with the depiction of resonantly British milieux’ (ibid.: 32). Spicer argues that Ken Hughes’ films are the strongest examples of this attempt to marry the ‘pace and action’ of films noirs being produced in the US with subject matter and locations that are resolutely British. Of Hughes’ films, Spicer cites Wide Boy (1952), The House Across the Lake (1954), The Long Haul (1957) and The Brain Machine as examples of this trend.

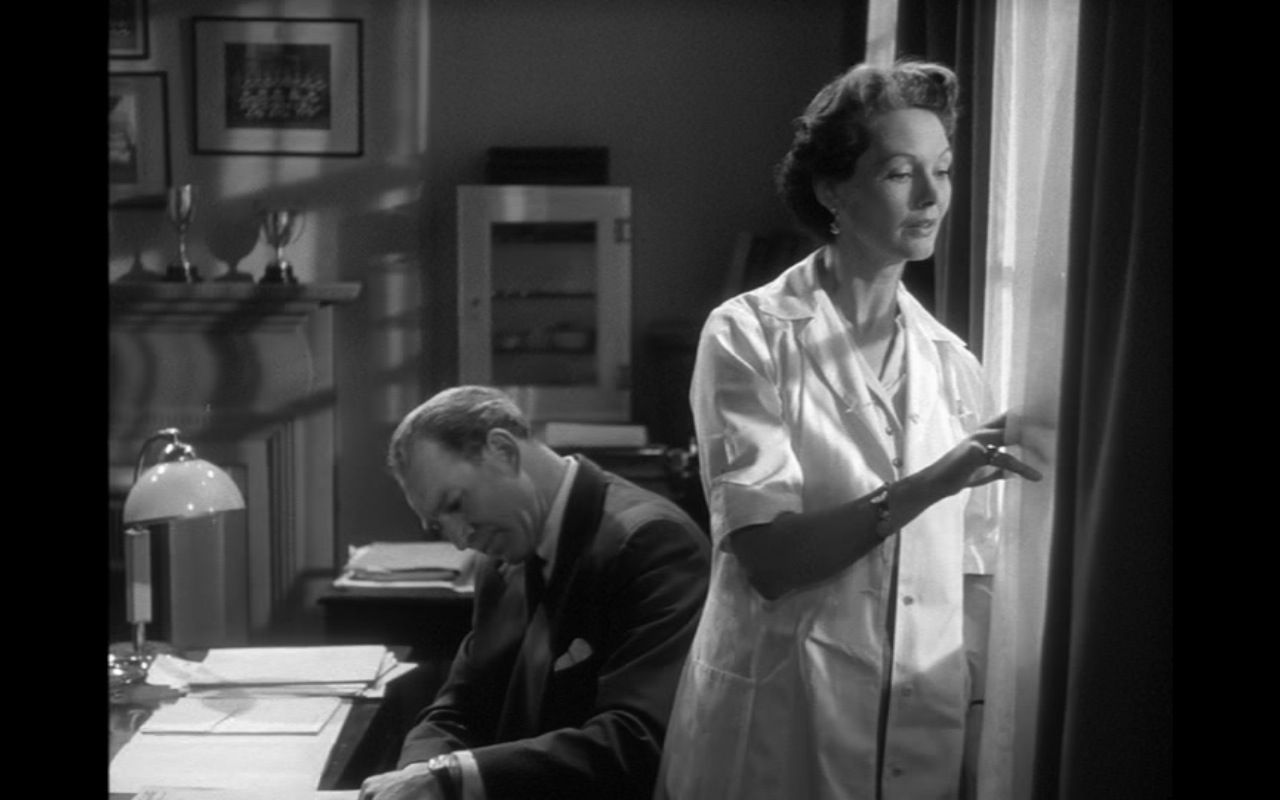

In the narrative of The Brain Machine, Spicer notes, Maxwell Reed plays ‘a brain-damaged, psychopathic gangster moving through an evocative underworld of sleazy tenements and seedy Soho nightclubs’ (ibid.). The film opens with a five-time murderer being delivered to the Regional Hospital for Mental Health where, in an upstairs office, the husband and wife team of Dr Geoffrey Allen (Patrick Barr) and Dr Phillipa Roberts (Elizabeth Allan) await their new patient’s arrival. ‘Your guinea pig has arrived’, Roberts tells her husband: ‘He looks harmless enough to me, more like a punch drunk prize fighter’. Allen, we soon learn, is pioneering the use of a machine which measures electrical impulses in the brain, enabling him to identify subjects whose brain patterns are ‘abnormal’ and who therefore may be predisposed to committing acts of violence. ‘Well, you didn’t have to bring him here to find out whether he was nuts or not. I could have told you that’, one of the orderlies who brought the murderer to the hospital says when he sees Allen and Roberts’ new subject connected to the ‘brain machine’.  Dissatisfied with her marriage, Roberts leaves Allen, accusing him of being a workaholic, and acquires a job at a hospital. She is soon asked to take a look at a new admission: a man with amnesia that appears to have been caused by a head trauma. Unable to get the patient to remember his name, Roberts hypnotises the man and discovers that he is Frank Smith, a thirty-one year old van driver. She asks Smith, under hypnosis, to recall the accident that caused his head trauma. He was hit over the head whilst being mugged, he claims: the men were ‘a couple of Simon’s boys [….] He wants to get me. He tried it once before and it didn’t work’. Seeking more information about her patient, Roberts also attaches Smith to the ‘brain machine’. Dissatisfied with her marriage, Roberts leaves Allen, accusing him of being a workaholic, and acquires a job at a hospital. She is soon asked to take a look at a new admission: a man with amnesia that appears to have been caused by a head trauma. Unable to get the patient to remember his name, Roberts hypnotises the man and discovers that he is Frank Smith, a thirty-one year old van driver. She asks Smith, under hypnosis, to recall the accident that caused his head trauma. He was hit over the head whilst being mugged, he claims: the men were ‘a couple of Simon’s boys [….] He wants to get me. He tried it once before and it didn’t work’. Seeking more information about her patient, Roberts also attaches Smith to the ‘brain machine’.

Within days, Smith discharges himself. Roberts suggests that he should be apprehended because the results from the ‘brain machine’ demonstrate that his brain waves are ‘abnormal’, much like those of the murderer in the film’s opening sequence, and therefore likely to become involved in a violent incident. However, the police resist Roberts’ suggestion that they should arrest Smith, reminding her that he has not (yet) committed a crime. One evening, outside the hospital, Smith catches up with Roberts and, holding her at gunpoint, takes her hostage. When Roberts’ disappearance has been noted, Allen attempts to hunt down Smith, and the remainder of the film juxtaposes Allen’s attempts to find Roberts and Roberts’ attempts to escape from the clutches of Smith. In European Film Noir (2007), Spicer has argued that The Brain Machine is both ‘the most satisfying of Hughes’ modestly stylish thrillers’ and also ‘the most English’ (101). Elizabeth Allan’s protagonist, Dr Roberts, is ‘an unusually mature, intelligent heroine’, and ‘Hughes conjures up an appropriately noirish atmosphere in gloomy hospitals and night-time streets’ (ibid.). Roberts is indeed a rather unconventional female character for the time period: her relationship with Allen is sour from the opening moments of the film. ‘When we got married, you forgot to tell me that you were already married to this place [….] There was a marriage ceremony, wasn’t there? Or were you in surgery at the time?’, she tells him as she watches the murderer being escorted into the building from the window of Allen’s office. Her independent spirit is expressed in her words to Allen: ‘We’re parting on the best of terms. After all, we’re a modern couple’, she tells him. He asks if she wants to divorce him; she responds by saying that she isn’t sure ‘what I’ve got on my mind. I just need to think this thing out first’.  Roberts is a thoroughly modern woman who refuses to be defined by her femininity. As the murderer is escorted into the room in which the brain machine is kept, Roberts asks the orderlies to wait outside. ‘Yes, ma’am’, one of the orderlies responds. ‘Would you mind calling me doctor, not ma’am?’, she asks the orderly, reminding him of her professional authority. Later, when settled into her new job at the hospital, she once again asserts her independence by sharply rebuffing the romantic advances of a male colleague. Roberts is a thoroughly modern woman who refuses to be defined by her femininity. As the murderer is escorted into the room in which the brain machine is kept, Roberts asks the orderlies to wait outside. ‘Yes, ma’am’, one of the orderlies responds. ‘Would you mind calling me doctor, not ma’am?’, she asks the orderly, reminding him of her professional authority. Later, when settled into her new job at the hospital, she once again asserts her independence by sharply rebuffing the romantic advances of a male colleague.

The film offers a reductive, fatalistic view of criminal behaviour as something caused by ‘abnormal’ brain waves rather than free will or a complex web of circumstances. To some extent, the film is reminiscent of Philip K Dick’s famous and roughly contemporaneous short story ‘The Minority Report’ (1956), which depicts a future society in which ‘mutants’ who are claimed to have precognitive abilities are used to justify arrests of people who, the ‘precogs’ claim, are likely to will commit a violent crime in the near future. Dick’s examination of this theme is complex, highlighting the conflict between deterministic models of behaviour (ie, the concept that behaviour is pre-determined) and the concept of free will, and exploring the moral debate about detaining people in order to prevent crimes which, in the future, they may or may not commit. Dick also suggests subtly that labelling people in such a way may in fact be a self-fulfilling prophecy. (Dick’s story has strong echoes for today, as may be seen in the ways in which its basic premise has been adopted by the current American television series Person of Interest; CBS, 2011- .) On the other hand, The Brain Machine isn’t quite as complex in its exploration of this theme: within the film, the results of the ‘brain machine’ itself are never questioned, other than by the police – whose questioning of Roberts’ suggestion that Smith should be detained in order to prevent a future crime suggest simply that they are ignorant and the law they represent is ineffectual. Ultimately, the machine’s results (which claim that Smith’s ‘abnormal’ brain waves determine that he will commit a violent crime) are proven to be ‘true’. As a line of dialogue by Allen subtly suggests, the machine offers an ability to predict an individual’s behaviour without a need to comprehend her/his motives: ‘We have a complete medical history of this man. We even have a picture of his brain. But we don’t know anything about him’, Allen says when he’s called in to help identify and apprehend Smith following Roberts’ kidnapping.  The film subtly hints at the issues of privacy raised by the intrusive use of brain machine but doesn’t explore this theme in a great amount of depth. At one point, Roberts tells Smith that ‘Doctors are like priests’ inasmuch as both professions promote confidentiality and provoke confession. However, following the hypnosis session, when Roberts questions Smith about the attack on him, he lashes out angrily and delivers a line that underscores how frustrating the film’s lack of engagement with issues of privacy is: ‘You doctors, you’re all the same’, he rants: ‘You’re a bunch of long noses, always probing. What goes on in my head is my business’. The film subtly hints at the issues of privacy raised by the intrusive use of brain machine but doesn’t explore this theme in a great amount of depth. At one point, Roberts tells Smith that ‘Doctors are like priests’ inasmuch as both professions promote confidentiality and provoke confession. However, following the hypnosis session, when Roberts questions Smith about the attack on him, he lashes out angrily and delivers a line that underscores how frustrating the film’s lack of engagement with issues of privacy is: ‘You doctors, you’re all the same’, he rants: ‘You’re a bunch of long noses, always probing. What goes on in my head is my business’.

The film was originally cut by the BBFC for cinema distribution, although the new BBFC website lists neither the length of the film after the cuts were made, or details of the cuts made to it. However, the length of the film when submitted to the BBFC is identified as 83:37 mins. This converts to a PAL runtime of 80:16 mins. This release runs for 80:14 (PAL), including the Studiocanal logo which is 20 seconds in length – so the running time of this version of the film is approximately 20 seconds shorter than the version of the film that was submitted to the BBFC in 1954. Therefore, in the absence of more concrete evidence, it may reasonably be assumed that this release replicates some, if not all, of the cuts imposed by the BBFC for the film’s UK cinema release in 1954. (If you have any more information about the cuts made to the film on its original release, please let us know via our forums.)

Video

The film is presented in its original screen ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome photography is well-presented here: the image is very crisp, with strong contrast which enhances the effect of the low-key lighting used throughout much of the picture. In all, this is a very pleasing presentation of the film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track which is equally pleasing – clean and problem-free. There are no subtitles, sadly.

Extras

Extras include: - the film’s Italian titles (part mute) (1:32). These is the titles sequence created for the film’s Italian release (‘La droga maledetta’). - the film’s trailer (captionless) (1:32). - an image gallery (0:49) containing promotional images from the film’s original release.

Overall

The Brain Machine is a tense, exciting film that has some beautiful, moody film noir-type photography. However, some of its themes are frustratingly undercooked. For Spicer, one of the unique elements about The Brain Machine is its focus on ‘the sexual and class tension that underlies the edgy relationship between’ Dr Roberts and her kidnapper, and this is certainly one aspect of the film that works very nicely (2007: 101). Likewise, the tension between Dr Allen and the police, who wrinkle at Allen’s private attempts to investigate Smith, is also explored through some very strong dialogue (‘In this game, Dr Allen, no news is good news’, Allen is told by the police at one point; ‘What do you expect me to do in the meantime, go home and read a book?’, Allen asks angrily). Ultimately, it’s an interesting film that could have done a little more to explore some of its more interesting themes. This disc contains a very satisfying presentation of the picture. The Brain Machine is a tense, exciting film that has some beautiful, moody film noir-type photography. However, some of its themes are frustratingly undercooked. For Spicer, one of the unique elements about The Brain Machine is its focus on ‘the sexual and class tension that underlies the edgy relationship between’ Dr Roberts and her kidnapper, and this is certainly one aspect of the film that works very nicely (2007: 101). Likewise, the tension between Dr Allen and the police, who wrinkle at Allen’s private attempts to investigate Smith, is also explored through some very strong dialogue (‘In this game, Dr Allen, no news is good news’, Allen is told by the police at one point; ‘What do you expect me to do in the meantime, go home and read a book?’, Allen asks angrily). Ultimately, it’s an interesting film that could have done a little more to explore some of its more interesting themes. This disc contains a very satisfying presentation of the picture.

References: Spicer, Andrew, 2007: European Film Noir. Manchester University Press Spicer, Andrew, 2010: Historical Dictionary of Film Noir. Scarecrow Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network Releasing. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|