|

|

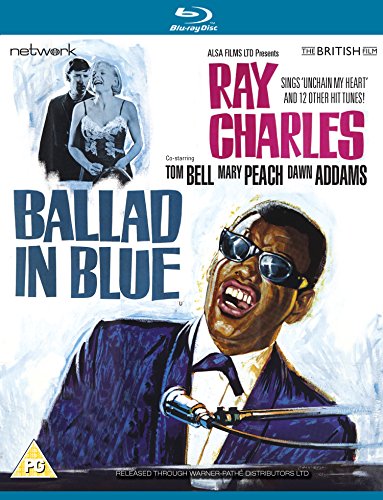

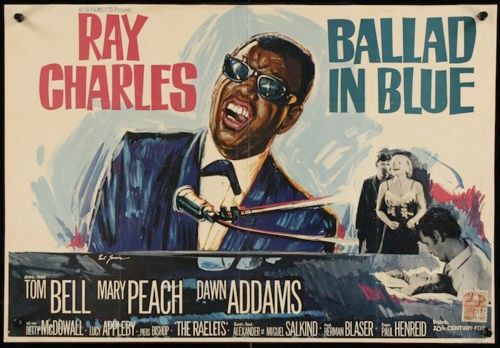

Ballad in Blue (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (15th June 2014). |

|

The Film

Ballad in Blue AKA Blues for Lovers (Paul Henreid, 1964) Ballad in Blue AKA Blues for Lovers (Paul Henreid, 1964)

Marking the first film in which Ray Charles appeared (Charles would subsequently make small appearances in films and television series from time to time), Ballad in Blue was directed by Paul Henreid. The film’s budget was low, and as a consequence most of it was shot in Ireland, where filming costs were cheaper than London (where the film begins) and Paris (where the narrative ends). Charles once commented that ‘It [the film] would have been much hipper if the folk making it hadn’t run out of money’ (Charles, quoted in Evans, 2007: np). During shooting, the picture was originally titled Light out of Darkness, which is also the title of one of the songs Charles wrote for the film. (This track, along with another original composition recorded for the movie, ‘Please Forgive and Forget’, would appear on Charles’ album Together Again.) However, on its release the film was retitled Ballad in Blue (and was distributed in America under the title Blues for Lovers). After an opening titles sequence over which Charles sings ‘Let the Good Times Roll’, the film begins with Charles performing one of his most famous hits, ‘Hit the Road Jack’ (from 1961), to the students of a special school for deaf children. Playing himself, Charles is at the school as a special guest; it’s a stop-off prior to delivering a concert in London before moving on to Paris. At the school, Charles meets an eight year old boy, David Harrison (Piers Bishop), and his mother Peggy (Mary Peach). Mary is a widow, and David became blind after contracting keratitis six months earlier. Intrigued by the boy, who demonstrates a rare strength of spirit, Charles offers David and Peggy a lift home. On the way, as they are driven by Charles’ assistant Fred (Joe Adams), Charles gives David his Braille watch. After dropping David and Peggy at their home, Fred observes that Peggy ‘kind of crowds’ David, and he ‘noticed when he [David] was talking to you [Charles] there was something kind of tough and gritty about him’. Peggy is conducting a relationship with Steve Collins (Tom Bell), a down-at-heel musician and composer. Whilst Steve and Peggy go out for the evening, David is cared for by Helen Babbidge (Betty McDowall) and her daughter Margaret (Lucy Appleby), who is somewhat spiteful towards the sweet-natured David. On their way home from their night out, Peggy and Steve stop by the location where Charles’ concert is taking place to return the watch, which Peggy considers to be too expensive for David to receive as a gift. ‘Too valuable for who? That little boy’, Charles states, ‘I don’t think so, and I paid for it’. When Peggy uses the word ‘charity’, Charles wrinkles, highlighting his and David’s shared blindness: ‘Coming from me, it wasn’t charity. It was sharing. David and I are in the same boat, remember?’  Impressed with Steve’s piano playing, Charles offers Steve a position arranging music for his performances. Steve accepts hesitantly, realising that this will involve moving around the world; Peggy is resistant, noting that ‘He [David] needs stability’. ‘I won’t take risks with my child’, Peggy asserts. Meanwhile, some of Steve’s friends snobbishly suggest he has sold his soul by agreeing to write and arrange pop music. Steve follows Charles to Paris, where he is met by an ex-girlfriend, Gina Graham (Dawn Addams). Gina attempts to seduce Steve; he resists, barely. He also arranges for David to visit an eye specialist in Paris, a man who, on the recommendation of Charles, may be able to restore the boy’s sight. Impressed with Steve’s piano playing, Charles offers Steve a position arranging music for his performances. Steve accepts hesitantly, realising that this will involve moving around the world; Peggy is resistant, noting that ‘He [David] needs stability’. ‘I won’t take risks with my child’, Peggy asserts. Meanwhile, some of Steve’s friends snobbishly suggest he has sold his soul by agreeing to write and arrange pop music. Steve follows Charles to Paris, where he is met by an ex-girlfriend, Gina Graham (Dawn Addams). Gina attempts to seduce Steve; he resists, barely. He also arranges for David to visit an eye specialist in Paris, a man who, on the recommendation of Charles, may be able to restore the boy’s sight.

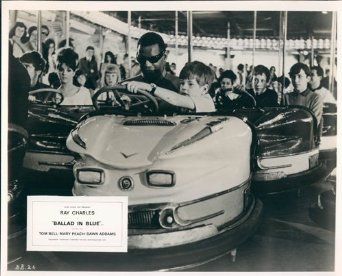

At the centre of the film is Charles’ relationship with David. David is mollycoddled by his mother, much to his chagrin. Early in the film, she baths him, and David comments, ‘You didn’t used to do this before I got blind’ before insisting, ‘I don’t really need looking after’, before noting, ‘I’m going to grow up like Mr Charles’. Steve has a much more pragmatic relationship with David, and the two develop a strong bond. (This is helped by a characteristically excellent performance from Tom Bell.) At one point, David confides in Steve, ‘She [Peggy] treats me like a baby when you’re not there. I hate being made to feel helpless’. Charles tries to encourage Peggy to give David more space to develop as an individual, not to dominate his life so much. Things come to a head when, in Paris, Charles takes David to a funfair and the overprotective Peggy watches on, horrified, as David rides the dodgems, first with Charles and then alone. Later, they visit one of Charles’ concerts and, in the throng outside, David is separated from his mother. It’s a horrifying experience which traumatises David, and in response Peggy threatens to return home without allowing David to see the specialist. However, Charles asks her to his room and delivers a strong monologue which, despite Charles’ weakness as an actor in some of the other scenes, seems utterly heartfelt: ‘You don’t really want David to see again’, he tells her: ‘You only think you do [….] Now listen to me, and you listen good [….] I know the mistakes most people can make if they don’t think [….] David needs all the help and understanding he can get. Help so he can become as independent as possible; understanding to help overcome this ordeal he’s now going through. But instead of encouraging the boy, you make him depend on you more and more’. Charles’ life during the production of the film was reputedly fraught with tension: at this point in his life, Charles was addicted to heroin, and he and the other members of his band who were similarly afflicted, struggled to score in Dublin and therefore ‘lived through the six weeks [of the shoot] on the nervous edge of withdrawal’ (Lydon, 2004: 241). To compound this issue, the mother of one of Charles’ daughters, Mae Mosely Lyles, flew to Dublin to confront Charles about his new relationship with a Finnish journlist named Rita (ibid.).  Charles reputedly found the experience of acting to be unnerving, but was convinced to work on the film because he liked the story (and the theme of a resilient young boy being coaxed to overcome his blindness), and realised that, as he was playing himself, the job of acting in the picture shouldn’t be too difficult (see Lydon, op cit.: 241). At the time, Charles told reporters that, ‘It’s [shooting the film is] fun for me because I don’t have to act [….] All I have to do is be myself. I’ve found it isn’t all that hard to be myself. If I had to act I would turn it down completely. I am no actor, and I have the sense to realise that and remind myself of that’ (Charles, quoted in Evans, op cit.: np). Charles reputedly found the experience of acting to be unnerving, but was convinced to work on the film because he liked the story (and the theme of a resilient young boy being coaxed to overcome his blindness), and realised that, as he was playing himself, the job of acting in the picture shouldn’t be too difficult (see Lydon, op cit.: 241). At the time, Charles told reporters that, ‘It’s [shooting the film is] fun for me because I don’t have to act [….] All I have to do is be myself. I’ve found it isn’t all that hard to be myself. If I had to act I would turn it down completely. I am no actor, and I have the sense to realise that and remind myself of that’ (Charles, quoted in Evans, op cit.: np).

As Michael Lydon notes, the film ‘is stiffly written, acted, and directed’: the script for the picture ‘makes Ray a plaster saint full of pious maxims’, and Charles is often left to ‘sit […] motionless waiting for his cue and then tonelessly recites the line he’d memorised from the Braille script’ (ibid.: 242). However, Charles isn’t the only reason to see the film: the rest of the cast, especially Tom Bell and Piers Bishop (who plays David) are very good in their roles. Mary Peach also offers an intriguing performance as David’s highly-strung mother. Interestingly, the film’s denouement leaves ambiguous the success (or not) of the procedure that David has undergone to ‘cure’ his blindness: the issue at the heart of the film is not finding a magical cure for David’s blindness, but the argument that David’s independence and autonomy should not be stifled by an overbearing, albeit well-meaning, parent. This narrative is punctuated by nine songs performed by Charles, including two original compositions, ‘Please Forgive and Forget’ and ‘Light out of Darkness’, which would later appear on Charles’ album Together Again. The film is uncut and runs for 88:26 mins.

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.33:1, although looking at the headroom, the compositions seem to have been intended for exhibition at a slightly wider screen ratio (possibly 1.66:1). The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The presentation has an organic look: there is no evidence of overzealous noise reduction or sharpening. There's good tonality on display within the monochrome photography, and on the whole this presentation exhibits a strong level of detail. However, it doesn’t quite have the depth of, say, Network’s recent HD release of Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963). Please note that the images used in this review are for illustration purposes only and do not reflect the quality of the transfer on Network’s Blu-ray disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is clean and clear throughout. The track on the whole is very bassy. There is some clipping in the lower frequencies. Optional English subtitles are provided.

Extras

The disc includes an image gallery (2:10).

Overall

Ballad in Blue is an interesting, not wholly successful, film. Although billed as a vehicle for Ray Charles, it’s perhaps best approached as a sixties drama that is punctuated by Charles’ songs and features a cameo by the singer. The film sometimes struggles to find focus: the central narrative revolves around David’s plight, but even within its compact running time (a good chunk of which is eaten up by Charles’ performances) the picture deviates from this to encompass Steve’s relationships with his friends and, in particular, his ex-mistress Gina. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting film with a strong and uplifting message, and Charles’ musical performances are delivered with gusto. Ballad in Blue is an interesting, not wholly successful, film. Although billed as a vehicle for Ray Charles, it’s perhaps best approached as a sixties drama that is punctuated by Charles’ songs and features a cameo by the singer. The film sometimes struggles to find focus: the central narrative revolves around David’s plight, but even within its compact running time (a good chunk of which is eaten up by Charles’ performances) the picture deviates from this to encompass Steve’s relationships with his friends and, in particular, his ex-mistress Gina. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting film with a strong and uplifting message, and Charles’ musical performances are delivered with gusto.

This Blu-ray contains a decent presentation of the film. The lossless audio track exhibits some clipping here and there, but it’s clear throughout, and the monochrome image is well-represented here. However, it's clear from the compositions that this should be presented in a wider screen ratio (1.66:1 or 1.75:1, most likely). Sadly, there is very little in the way of contextual material: given the obscure history of this film (considering Charles’ role in it), it would have been interesting to see some kind of retrospective feature about the film. Regardless of this, however, this is a fine presentation of an interesting, if not completely successful, film. References: Evans, Michael, 2007: Ray Charles: The Birth of Soul. London: Omnibus Press Lydon, Michael, 2004: Ray Charles: Man and Music. London: Routledge This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|