|

|

Goto, Isle of Love AKA Goto, l'île d'amour AKA Goto, Island of Love (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (5th September 2014). |

|

The Film

Goto, l’île d’amour / Goto, Island of Love (Walerian Borowczyk, 1968)  This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release. This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release.

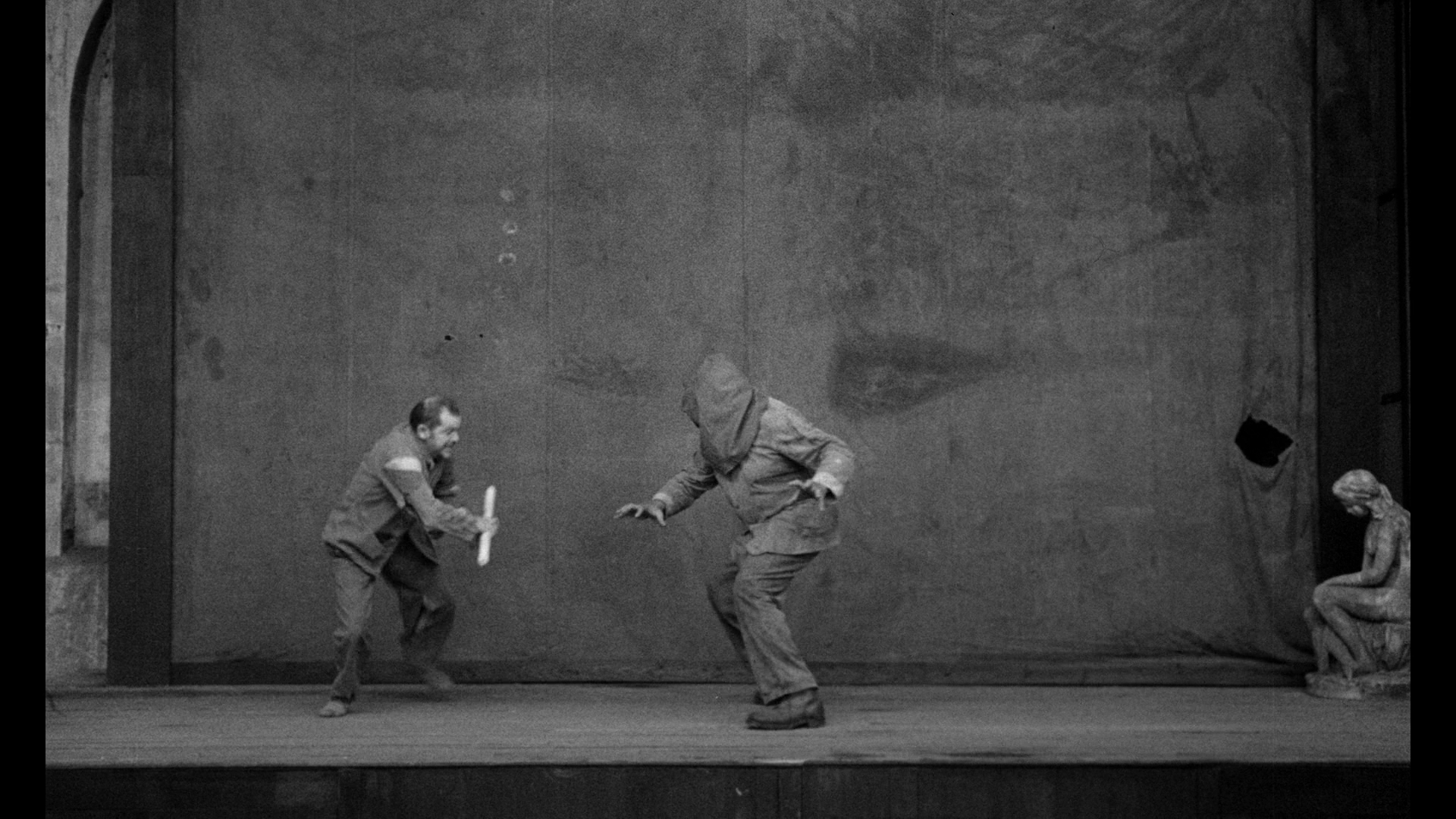

NB. Links to reviews of the other Borowczyk discs will be added to this review as they go ‘live’ over the coming week. Our review of Blanche (1971) can be found here. Our review of The Beast (1975) can be found here. Our review of Immoral Tales (1974) can be found here. - Our review of Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation can be found here. Walerian Borowczyk’s first live-action feature (and his second feature film after the animated Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal, 1967), Goto, l’île d’amour (1968) is a fascinating film that shows continuation of some of the ideas within Borowczyk’s animated shorts (and, of course, his previous feature film) whilst also looking forwards to some of the themes of his later live-action pictures. In particular, Goto has some significant similarities with Borowczyk’s subsequent film, Blanche (1971). Both films feature Borowczyk’s wife Ligia Branice in the role of a woman married to an older man who is a figure of authority; and in both films, Branice’s character is pursued romantically by several other men, leading to tragic consequences.  In Goto, Branice plays Glossia, the wife of Goto III, the leader of an isolated island community-cum-totalitarian state, also called Goto. The inhabitants of the island seem to live exclusively within a large fortress. From an early age, in the classroom children are indoctrinated into the ways of the island community, learning about the history of the island and the identities of its ‘great leaders’: Goto I, Goto II and Goto III (Pierre Brasseur). As adults, the island’s inhabitants wear military-style uniforms that make them appear virtually indistinguishable from one another, and they are given menial jobs. (The fortress in which the island’s inhabitants live, their regimented lifestyle, and their military-style uniforms suggest a military dictatorship; but as the island is utterly isolated from the rest of the world, there is no conflict between Goto and any other nation, and therefore the concept of military might is utterly redundant.) There is no unemployment, but barring Goto and his wife Glossia, everyone on the island lives within what is essentially a lumpenproletariat: there is no hint of rebellion, and clad in the same uniform, citizens of the state and prisoners who have been convicted of crimes appear almost identical in appearance. (Thus when Borowczyk shows Goto and Glossia watching a fight to the death between two prisoners, the participants in the battle are indistinguishable from the crowd watching them.) As if to reinforce the lack of individual identity within the inhabitants of this bizarre state, everyone’s first name begins with the letter ‘G’ (Goto, Glossia, Grono, Grozo, Gras, etc). In Goto, Branice plays Glossia, the wife of Goto III, the leader of an isolated island community-cum-totalitarian state, also called Goto. The inhabitants of the island seem to live exclusively within a large fortress. From an early age, in the classroom children are indoctrinated into the ways of the island community, learning about the history of the island and the identities of its ‘great leaders’: Goto I, Goto II and Goto III (Pierre Brasseur). As adults, the island’s inhabitants wear military-style uniforms that make them appear virtually indistinguishable from one another, and they are given menial jobs. (The fortress in which the island’s inhabitants live, their regimented lifestyle, and their military-style uniforms suggest a military dictatorship; but as the island is utterly isolated from the rest of the world, there is no conflict between Goto and any other nation, and therefore the concept of military might is utterly redundant.) There is no unemployment, but barring Goto and his wife Glossia, everyone on the island lives within what is essentially a lumpenproletariat: there is no hint of rebellion, and clad in the same uniform, citizens of the state and prisoners who have been convicted of crimes appear almost identical in appearance. (Thus when Borowczyk shows Goto and Glossia watching a fight to the death between two prisoners, the participants in the battle are indistinguishable from the crowd watching them.) As if to reinforce the lack of individual identity within the inhabitants of this bizarre state, everyone’s first name begins with the letter ‘G’ (Goto, Glossia, Grono, Grozo, Gras, etc).

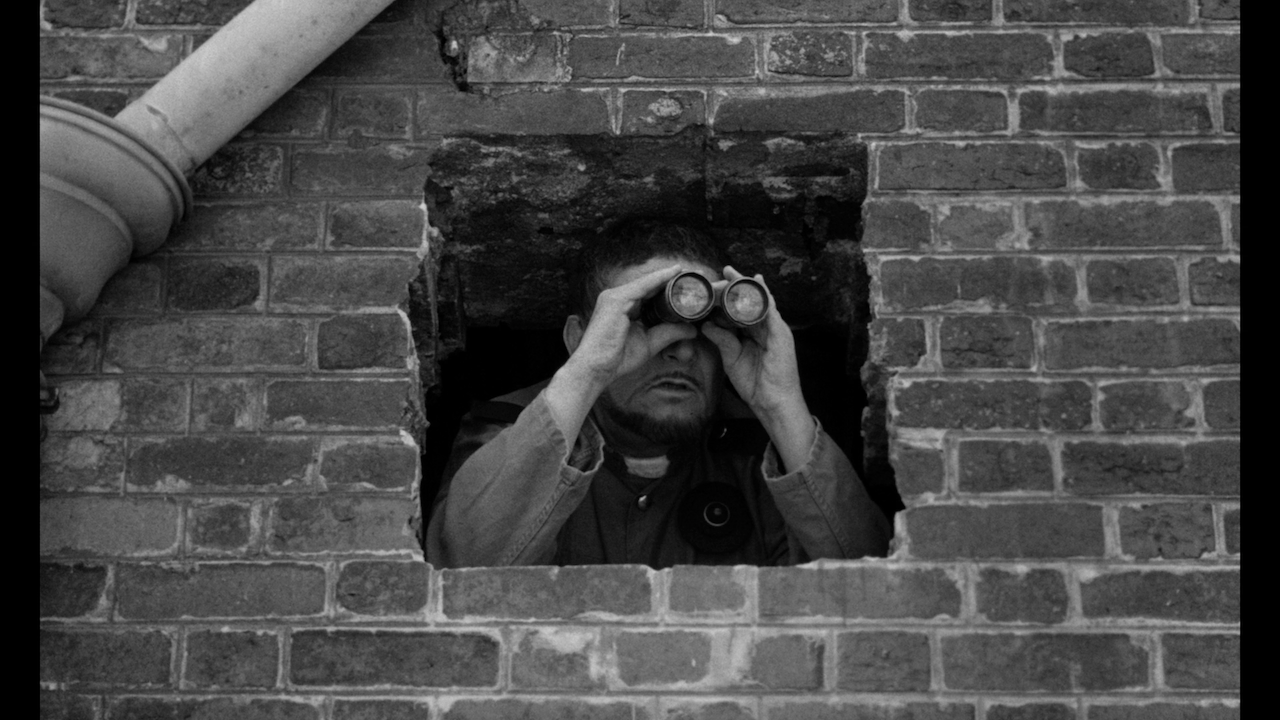

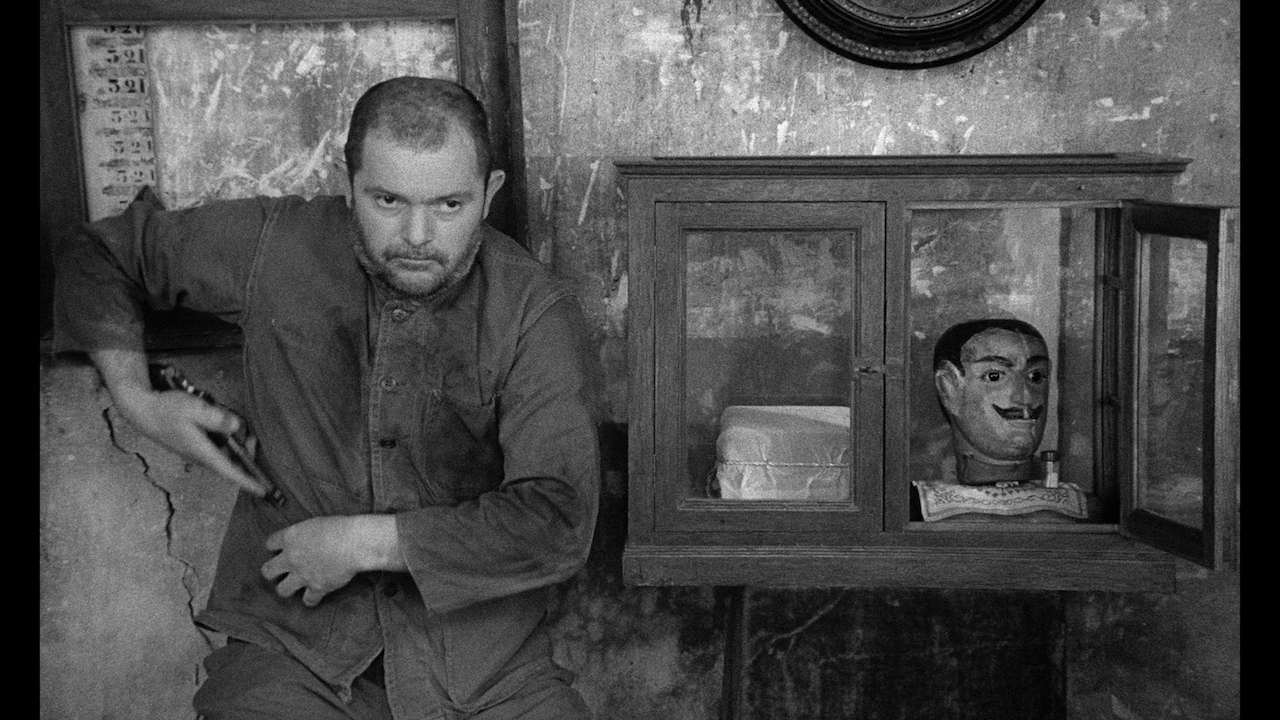

Goto III and Glossia attend a battle between two mismatched prisoners in which the loser will be executed: the huge Gras (Michel Thomass), a brute of a man who has been convicted of the murder of Corporal Gat; and the diminutive Grozo (Guy Saint-Jean), who stole the binoculars of Lieutenant Gono (Jean-Pierre Andréani). Goto and Glossia take pity on Grozo, and Goto offers Grozo his freedom, proposing that Grozo become the apprentice of Glossia’s father Gomor (René Dary). Gomor takes care of Goto’s dogs, cleans and cares for Goto and Glossia’s boots, and is also the state’s principal fly catcher. However, after a disagreement Grozo murders Gomor, suffocating him. Gomor’s death is presumed to be of natural causes; Grozo is promoted to Gomor’s position and given an apprentice of his own.  Glossia is taking riding lessons, and she is secretly conducting an affair with her instructor, Lieutenant Gono. When Goto discovers this, whilst in the hay loft with Grozo (who is there to place fly traps), he gives Grozo his revolver, with the implicit suggestion that Grozo will assassinate Gono (and possibly Glossia too). However, Grozo turns the gun on Goto, killing him. Goto, it seems, is also in love with Glossia, and in the power vacuum that follows Goto’s death, Grozo attempts to seize the chance to get closer to the object of his affections. Glossia is taking riding lessons, and she is secretly conducting an affair with her instructor, Lieutenant Gono. When Goto discovers this, whilst in the hay loft with Grozo (who is there to place fly traps), he gives Grozo his revolver, with the implicit suggestion that Grozo will assassinate Gono (and possibly Glossia too). However, Grozo turns the gun on Goto, killing him. Goto, it seems, is also in love with Glossia, and in the power vacuum that follows Goto’s death, Grozo attempts to seize the chance to get closer to the object of his affections.

Daniel Bird notes that recurring tropes within Borowczyk’s work are consolidated here: the ‘use of classical music [in this case, Handel’s organ concertos], an insular […] location in which the narrative unfolds and which becomes a world unto itself, one overrun with desire and sexuality; the position of women in structures of patriarchy; and the juxtaposition of its characters with fable-like and mythical beings’ (Bird, 2011: 160). Bird also reminds us that in his animated shorts, Borowczyk frequently demonstrates ‘a strong distrust of modernized society, organized religion and governmental power’ (ibid.). Likewise, at the centre of Goto is the relationship between desire and power, thematic material that forms the focus of Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1928) and novels such as George Orwell’s 1984 (1948) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931). The repressive regime within the film knows how to regulate desire for its own ends: hard work is rewarded by a visit to a brothel. It is in this brothel that Grozo taunts Glossia’s mother Gonasta (Ginette Leclerc) by making her wear Glossia’s discarded clothes.  Furthermore, education is used as a form of indoctrination. The children in the schoolroom are taught about the history of the island. In 1887, we are told (by the teacher in the schoolroom, played by Fernand Bercher, who addresses the film’s viewer as much as his students) the island suffered an earthquake which killed much of the population, including the royal family. ‘[S]ince 1887’, the teacher says, ‘royal status has been deferred onto our governors although not officially assumed by them’. These governors, the Gotos, ‘faithfully preserved the pre-earthquake way of life’, to the point that the clocks have stopped and time no longer advances. As Michael Richardson has suggested, ‘the fact that the clocks don’t work’ underscores the extent to which the society in the film is one that is ‘marked by inertia’; within this context ‘one feels that any action, any sign of passion, might immediately bring down the social order’ (Richardson, 2006: 110). Meanwhile, Jonathan Owen argues that the fact that ‘time has literally stopped within the fortress can be seen to render Goto as much a vision of the living dead as [Alain Resnais’ Last Year at] Marienbad’ (Owen, 2014: 230).  The teacher shows his students a portrait, asking one student in front of him, Gera, to tell him ‘whose portrait this is’. Gera responds by saying, ‘His Highness, Goto III, governor of the Isle of Goto’. The teacher then asks another student (Gora) to his right to tell him ‘whose portrait this is’. Gora responds by asserting, ‘His Highness, Goto I, governor of the island of Goto’. Finally, the teacher asks an additional student (Gomo) to his left the same question. Gomo hesitates before telling him that the portrait is of Goto II. The image is in fact an optical effect: all three portraits are present within the frame, the portrait of Goto III face-on, and the portraits of Goto I and Goto II in profile. Returning the portrait to its position on the wall behind his desk, the teacher tells the students ‘Each side [of the classroom] sees a different picture. You’ll change places each week’. Michael Richardson has argued that this sequence may be interpreted in several ways: as a ‘comment on the Christian trinity, or a manifestation of the divine right of kings’, or as ‘a commentary on the way that reality changes depending on the angle from which it is viewed, or an illustration of the philosophical point made by Permenides that change is merely a matter of appearance and in reality nothing changes’ (op cit.: 110). Certainly, the island’s national anthem positions governor ‘Goto’ (without specifying which one; all the Gotos share an identity) as the saviour of the island of Goto: ‘The storms are fled afar / No longer we hostages are / Of Nature hostile / Goto protects our isle’, the schoolchildren sing prior to the public fight that will take place between the two prisoners, Grozo and Gras. The teacher shows his students a portrait, asking one student in front of him, Gera, to tell him ‘whose portrait this is’. Gera responds by saying, ‘His Highness, Goto III, governor of the Isle of Goto’. The teacher then asks another student (Gora) to his right to tell him ‘whose portrait this is’. Gora responds by asserting, ‘His Highness, Goto I, governor of the island of Goto’. Finally, the teacher asks an additional student (Gomo) to his left the same question. Gomo hesitates before telling him that the portrait is of Goto II. The image is in fact an optical effect: all three portraits are present within the frame, the portrait of Goto III face-on, and the portraits of Goto I and Goto II in profile. Returning the portrait to its position on the wall behind his desk, the teacher tells the students ‘Each side [of the classroom] sees a different picture. You’ll change places each week’. Michael Richardson has argued that this sequence may be interpreted in several ways: as a ‘comment on the Christian trinity, or a manifestation of the divine right of kings’, or as ‘a commentary on the way that reality changes depending on the angle from which it is viewed, or an illustration of the philosophical point made by Permenides that change is merely a matter of appearance and in reality nothing changes’ (op cit.: 110). Certainly, the island’s national anthem positions governor ‘Goto’ (without specifying which one; all the Gotos share an identity) as the saviour of the island of Goto: ‘The storms are fled afar / No longer we hostages are / Of Nature hostile / Goto protects our isle’, the schoolchildren sing prior to the public fight that will take place between the two prisoners, Grozo and Gras.

The fight between Grozo and Gras that takes place towards the beginning of the film represents the island’s curious sense of justice. As Jonathan Owen notes, the combat between prisoners, which is used to determine which of the prisoners is condemned to death, represents a form of ‘institutionalized chance’: the crimes (murder and theft) are not equal, and Grozo and Gras are mismatched too (Owen, 2014: 230). Grozo and Gras – the former convicted of stealing an officer’s binoculars; the latter convicted of the very different crime of murder – are forced to fight in front of the audience. We are told that ‘although both crimes warrant the death sentence, only one will die: the loser’. The inmate who loses the fight will be executed by guillotine. (The odds are evened slightly when Gras is blindfolded and Grozo is given a club.) Jonathan Owen suggests that the ‘disordered and incoherent’ rhetoric and policies of the state within the film ‘may be said to indicate the real disorder, incoherence, and philosophical nullity of existing power, the contradiction of a rigorous political order that is underpinned by a feeble intellectual order’ (ibid.). Upon rescuing him from death, Goto III gives Grozo a set of ‘chores comprising a peremptory, official, yet nonsensical yoking together of dogs, shoes, and flies’ (Owen, op cit.: 228). Grozo is, of course, pardoned by Goto and Glossia, and given a gainful job working as the apprentice of Gomor, caring for Goto’s dogs, cleaning Goto and Glossia’s boots, and acting as the fortress’ fly catcher: Goto tells Grozo he will ‘replace the old man [Gomor] who keeps my kennels’ and will also become ‘killer of flies and cleaner of our boots’. (Ironically, when introduced to Gras prior to the public fight, Gras threatened to swat Grozo ‘like a fly’.)  As the film progresses, Grozo becomes an increasingly effective manipulator of events. He begins the film as a simple thief, who has stolen the binoculars of a superior officer. By the end of the film, he has committed two murders and has, through his wiles, manoeuvred himself into the position of the island’s new governor – a position Grozo has achieved through nothing more than a playground game that involves spinning a boot-polishing rack. Guy Saint-Jean plays Grozo as if he were an increasingly spiteful child, entirely lacking in conscience in his pursuit of the object of his affections, Glossia. As the film progresses, Grozo becomes an increasingly effective manipulator of events. He begins the film as a simple thief, who has stolen the binoculars of a superior officer. By the end of the film, he has committed two murders and has, through his wiles, manoeuvred himself into the position of the island’s new governor – a position Grozo has achieved through nothing more than a playground game that involves spinning a boot-polishing rack. Guy Saint-Jean plays Grozo as if he were an increasingly spiteful child, entirely lacking in conscience in his pursuit of the object of his affections, Glossia.

Fetishism of objects is a recurring motif throughout the film. Grozo stole Gono’s binoculars and, when Goto offers him the opportunity to look through Goto’s own binoculars, Grozo freezes like a recovering junkie who has been offered a fix. Grozo tells Goto that, after seeing Gras executed, he swore he would never touch binoculars again. Goto insists Grozo look through the binoculars. ‘I’d be afraid’, Grozo says. ‘To refuse or to look?’, Goto asks. ‘I’m not sure. They’re both pretty bad’, Grozo responds, adding, ‘It’s a dangerous game, Your Highness’. Later, after shooting Goto, Grozo lovingly caresses Glossia’s boots whilst cleaning and polishing them. (Notably, when Goto tells Grozo he will be ‘cleaner of our boots’, Borowczyk cuts to a colour close-up of Glossia’s shoes as she walks across a wooden floor: even at this early stage of the narrative, there’s the suggestion that Glossia’s shoes are fetishised in the mind of Grozo.) Gomor’s fly traps are also fetish objects of sorts, their workings described in detail by Gomor to Grozo. The traps have been devised to catch all types of flies, including (Gomor tells Grozo) older, wiser flies that have learnt to evade other types of trap. As Gomor ‘the fly vanquisher’ explains to Grozo, the funnels by which the flies access the trap have a curtain of hair that prevents egress by the fly: ‘The fly thinks the same way as you’, Gomor tells his apprentice, ‘Entering is easy, but later it’s sorry as hell’. As if to foreground the extent to which this description of the fly trap acts as a metaphor for the totalitarian regime on the island of Goto, Grozo responds by asserting, ‘Don’t compare me to a fly, because… [he struggles to find a reason, eventually settling on something characteristically childish] I might get angry’. (And, as we discover later, the inhabitants of Goto wouldn’t like Grozo when he’s angry.) As Owen notes, highlighting the metaphoric qualities of the fly trap and also its potential as the object of a fetish, the trap, designed to allow flies to enter but render them unable to leave, is symbolic of the fortress’ ‘cruelly concentrationary nature’ but ‘is also a Meret Oppenheim-like surrealist object with erotic connotations’ (Owen, op cit.: 231).  >Glossia and Gono plan to escape from the island using a rowboat that has been concealed on one of the beaches. However, Goto accidentally discovers this rowboat (‘Someone’s coming or someone’s going’, he jokes) and, claiming the vessel is ‘A boat for suicides’, cuts the rope tying it to the shore, allowing it to be wrecked by the tide and the rocks. Glossia looks on, tears in her eyes, her hope of escaping from the island with Gono vanquished. Borowczyk cuts to this image repeatedly, filling it with symbolic power: the image represents the wrecking of Glossia’s dreams of escape and, ultimately, the possibility for a ‘happy ending’. >Glossia and Gono plan to escape from the island using a rowboat that has been concealed on one of the beaches. However, Goto accidentally discovers this rowboat (‘Someone’s coming or someone’s going’, he jokes) and, claiming the vessel is ‘A boat for suicides’, cuts the rope tying it to the shore, allowing it to be wrecked by the tide and the rocks. Glossia looks on, tears in her eyes, her hope of escaping from the island with Gono vanquished. Borowczyk cuts to this image repeatedly, filling it with symbolic power: the image represents the wrecking of Glossia’s dreams of escape and, ultimately, the possibility for a ‘happy ending’.

Goto is a complicated character, played subtly by Brasseur. Goto is authoritative and stern, metonymically connected to the aggressive black dogs that are kept in his name; but at the same time he is able to recognise beauty (‘What an art! What a sense of rhythm! Pure music!’, he explains whilst watching the expert horsemen practise their craft), playful (he hides amongst the rocks with Glossia, playing a game like a child) and sympathetic towards those under him – though he cannot offer solutions to their plight. In one sequence, he encounters a young girl, Gauda, escorting a donkey; Gauda’s baby brother is in a pannier on the donkey. Goto enquires about the girl’s family: her mother is dead, and she is taking lunch to her father and older brother, who both work at the quarry. Goto listens sympathetically but offers the girl no aid or support. When he commissions Grozo to execute Gono (and possibly Glossia too), he does so implicitly. After both Grozo and Goto, using Goto’s binoculars to view out of the window in the hay loft, spot Gono and Glossia together, Grozo subtly declares that Gono is ‘carrying my binoculars’. ‘I permit you to get them back’, Goto answers solemnly, handing Grozo his revolver, with the clear intention that Grozo is to kill Gono. However, Grozo shoots Gono, later framing Gono for the crime, so as to remove the barriers preventing him from approaching Glossia.  Fittingly, given the film’s Kafkaesque examination of authority and power, the production of the film was halted by the events of May, 1968. (In the featurette on this disc, we are told that during this time, headlines in newspapers declared that Borowczyk and his crew were barricaded within a factory, where the film was being shot, with guns – which were in fact props that were being used in the film.) The film is uncut and runs for 95:02 mins.

Video

In the featurette included on this disc, the film’s camera operator, Noël Véry, notes that with this film, Borowczyk opted to use lenses with focal lengths above 75mm. This meant there was no distortion within the film frame (as would be seen with the use of wide-angle lenses, for example). The telephoto lenses used during production also offered a flattening of perspective that, combined with the frontal compositions, make shots become like tableaux (or possibly, tableaux vivants). The aesthetic of the film is dominated by carefully-studied, almost uniformly ‘flat’ compositions, and could thus perhaps best be described as ‘painterly’. (Borowczyk used a similar technique in Blanche, resulting in images that offered a pastiche of Medieval tapestries.) In the featurette included on this disc, the film’s camera operator, Noël Véry, notes that with this film, Borowczyk opted to use lenses with focal lengths above 75mm. This meant there was no distortion within the film frame (as would be seen with the use of wide-angle lenses, for example). The telephoto lenses used during production also offered a flattening of perspective that, combined with the frontal compositions, make shots become like tableaux (or possibly, tableaux vivants). The aesthetic of the film is dominated by carefully-studied, almost uniformly ‘flat’ compositions, and could thus perhaps best be described as ‘painterly’. (Borowczyk used a similar technique in Blanche, resulting in images that offered a pastiche of Medieval tapestries.)

Borowczyk’s animated shorts often included live-action inserts. Likewise, this monochrome film includes colour inserts – usually to denote moments of stress and anxiety for the characters. When Gras is executed, for example, we are presented with a colour close-up of the bucket containing his blood being wheeled away on a trolley. The film begins with a brief description of the restoration work (in the absence of the original negative, now lost, the bulk of the film was taken from a 35mm finegrain positive, with some footage, including the colour inserts, taken from a 35mm duplicate negative). Previous home video releases of the film had left a lot to be desired. Details of the work that went towards restoring Goto can be found at Arrow’s ‘The Video Deck’ blog, written by James White: http://arrowvideodeck.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/camera-obscura-james-white-on.html.  The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, taking up a little over 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, taking up a little over 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.

The film’s natural grain is resolved well within the encode, and as James White mentions in the online blog linked to above, care was taken not to obliterate some of the film’s peculiar ‘texture’ (the scarred walls of the fortress, the air of the stables filled with dust and flies), resulting in a very painstaking process of removing dirt and debris from the materials manually, rather than by automatic means. This care and attention is evident throughout the presentation. The predominantly monochrome image displays excellent contrast and tonality, with strong mid-tones and detail in the highlights and shadows, where the original photography allows. The level of detail, in comparison with previous home video releases, is astounding; and the film, like the island community depicted within it, has a texture all of its own. NB. Larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM mono track (in French), with optional English subtitles. The subtitles are very effective in conveying the nuances of the dialogue – for example, the teacher’s stumbling over the phrase ‘the mouths of the flies’, in an early sequence. The track has a strong sense of range.

Extras

The disc includes: - an introduction by artist Craigie Horsfield (8:13). Horsfield discusses his personal relationship with the film (he went to art school with John Goto, who was so impressed with Borowczyk’s picture that he changed his surname). Horsfield talks about the ways in which the film blurs the boundaries between live action and graphics. He notes that Borowczyk’s films generally ‘look archaic in the ways they looked at the time: not actually archaic but odd’. He also reflects on the relationship between Borowczyk’s work and the work of Chris Marker: both artists, Horsfield argues, produced work of invention, exploration and wonder. - 'The Concentration Universe: Making Goto, Isle of Love' (21:24). In this featurette, actor Jean-Pierre Andréani (Gono), camera operator Noël Véry and Jean-Pierre Platel (the film’s focus puller) discuss the production of the film. All of the participants highlight Borowczyk’s attention to detail: for example, Borowczyk insisted on making the fly traps depicted within the film himself. (Véry calls Boro ‘artisan du film’). Prior to beginning work on the film, Andréani had just been demobbed from the French army, having served in Algeria; as a consequence, he found the film’s depiction of a militaristic regime fascinating, a ‘weird world’. He says that Borowczyk was constantly busy, but was ‘unobtrusive like he could rely on second sight’; both he and Platel state that Borowczyk was not ‘talkative’ and often communicated with the actors through his assistant. Véry discusses the film’s photography in some depth, noting that Borowczyk favoured ‘Frontal views, no perspective, no vanishing point, no wide-angle lenses, no distortion effect’. Borowczyk preferred lenses with a focal length above 75mm, which offered a flattening of perspective: he was aiming to achieve a photographic objectivity, with the photography being as neutral as possible. Véry also talks about the film’s lighting, stating that cinematographer Guy Durban had a ‘Boro light’ technique that he perfected in the short films on which he collaborated with the director: the light was diffused. 'The Profligate Door: Borowczyk's Sound Sculptures' (13:15). This featurette features curator Maurice Corbet discussing Borowczyk’s ‘sound sculptures’. Trailer (3:46)

Overall

Like Blanche (in Borowczyk’s subsequent film of the same name), Glossia is the tragic victim at the heart of the film, held under the thumb of Goto and eventually subjected to the Machiavellian machinations of Grozo. Grozo’s plot is solely for personal gain, motivated by his desire and his fetishisation of Glossia. Within the repressive regime depicted in the film’s narrative, there seems little to no hope of any revolt or revolution of any consequence. The citizens of the island colony seem destined to remain in this utterly isolated, frozen regime in which time, and any sense of forward progression, has stopped and every gesture seems futile. The film’s title seems to make an ironic allusion to French crooner Tino Rossi’s sappy 1944 film L'île d'amour (directed by Maurice Cam), a film for which Rossi sang one of his most mawkish hits, ‘Mon île d'amour’. However, Goto’s ‘île d'amour’ is far from the idealised island of love (Corsica) about which Rossi sang (‘Mon île d'amour / Qu'il fut beau le jour / Où sous le ciel sans un nuage / M'est apparue sa douce image’) – though one can imagine Grozo humming the tune to himself as he lovingly polishes/caresses Glossia’s boots. Like Blanche (in Borowczyk’s subsequent film of the same name), Glossia is the tragic victim at the heart of the film, held under the thumb of Goto and eventually subjected to the Machiavellian machinations of Grozo. Grozo’s plot is solely for personal gain, motivated by his desire and his fetishisation of Glossia. Within the repressive regime depicted in the film’s narrative, there seems little to no hope of any revolt or revolution of any consequence. The citizens of the island colony seem destined to remain in this utterly isolated, frozen regime in which time, and any sense of forward progression, has stopped and every gesture seems futile. The film’s title seems to make an ironic allusion to French crooner Tino Rossi’s sappy 1944 film L'île d'amour (directed by Maurice Cam), a film for which Rossi sang one of his most mawkish hits, ‘Mon île d'amour’. However, Goto’s ‘île d'amour’ is far from the idealised island of love (Corsica) about which Rossi sang (‘Mon île d'amour / Qu'il fut beau le jour / Où sous le ciel sans un nuage / M'est apparue sa douce image’) – though one can imagine Grozo humming the tune to himself as he lovingly polishes/caresses Glossia’s boots.

In writings about the film, commentators have compared the island of Goto to North Korea and, more fittingly given the context of the film’s production, French penal colonies such as the one that existed on Devil’s Island from 1852 to 1953. Both comparisons bear fruit. It’s certainly a film that, given the immediate context in which it was made (with the events of May, 1968 interrupting the shooting), is very timely – but also a film that has an arguably universal relevance, given its examination of the intersections between desire and power. Goto is an amazing film, sadly little seen. Hopefully, Arrow’s superb release will remedy this. The presentation on this disc is, as with all of the films included in Arrow’s Borowczyk set, absolutely first class. Goto has had a number of DVD releases (by Nouveaux Pictures in the UK, Cult Epics in the US and Arte in France), but this Blu-ray release from Arrow, with its fantastic restoration of the picture, leaves them in the shade. Sadly, Daniel Bird’s commentary from the Nouveaux Pictures DVD hasn’t been ported over to this release from Arrow, so completists may wish to hang on to their copies of that DVD, but the newly-commissioned extra features happily fill its place. Together, Arrow’s Borowczyk releases, whether purchased alone or as part of the Camera Obscura set, are amongst the best releases of the year. References Bird, Daniel, 2011: ‘Walerian Borowczyk’. In: Bingham, Adam (ed), 2011: Directory of World Cinema, Volume 8. London: Intellect Books Owen, Jonathan, 2014: ‘An Island Near the Left Bank: Walerian Borowczyk as a French Left Bank Filmmaker’. In: Mazierska, Ewa & Goddard, Michael (eds), 2014: Polish Cinema in a Transnatonal Context. University of Rochester Press: 215-35 Richardson, Michael, 2006: Surrealism and Cinema. Oxford: Berg

|

|||||

|