|

|

Twins of Evil AKA Twins of Dracula (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th September 2014). |

|

The Film

Twins of Evil (John Hough, 1971) Twins of Evil (John Hough, 1971)

Hammer’s horror films, especially its vampire pictures, had always carried something of a sexual frisson. However, in the early 1970s, as film censorship began to relax in both Britain and America (not to mention in Continental territories, as evidenced by, for example, the sexually explicit vampire fables of Jean Rollin), Hammer began to push the envelope somewhat: where the Hammer vampire pictures of the early 1960s had featured ‘backlit nightgowns, cleavage, and avidly sexual, if ambiguous expressions’, those of the 1970s emphasised ‘bare breasts and the occasional butt […] as well as thrashing and moaning’ (Day, 2002: 22). With their trio of films based on Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1871 Gothic novel Carmilla – The Vampire Lovers (Roy Ward Baker, 1970), Lust for a Vampire (Jimmy Sangster, 1971) and Twins of Evil (John Hough, 1971) – Hammer became increasingly risqué, moving away from the heterosexually-coded Dracula pictures to an exploration of the ‘vampire-attack-as-lesbian-seduction’, exploring the source novel’s potential for an increasing emphasis on female nudity and sexual content (ibid.). Where The Vampire Lovers and Lust for a Vampire had focused on a theme of cyclical rebirth, Twins of Evil chose to abandon the formula of the prior two Carmilla pictures in favour of focusing on the male character of Count Karnstein, whose function in the film is essentially as a substitute for Dracula. Initiated into a life of vampirism by the ghost of Mircalla, one of his ancestors, after committing a blood sacrifice in the name of the Devil, Karnstein seduces the wayward Frieda, turning her into a vampire. (This begs the question: who exactly is responsible for the exsanguinated corpses discovered around the village prior to Karnstein’s encounter with Mircalla?)  After the execution of a ‘witch’ by Gustav Weil (Peter Cushing) and his Puritan Brotherhood, Weil’s nieces, the twins Maria (Mary Collinson) and Frieda (Madeleine Collinson) Gellhorn arrive in the village of Karnstein, having (following the death of their parents) being left in the care of their aunt Katy Weil (Kathleen Byron) and their uncle Gustav. Upon arriving in the village, Maria and Frieda gaze in wonderment at Count Karnstein’s (Damien Thomas) castle, which overlooks the village. The village, it seems, has been plagued with a number of mysterious deaths: the exsanguinated bodies of young men who have gone missing from the village have been discovered in the surrounding forest. Weil’s Brotherhood have begun executing ‘witches’, who they presume to be somehow guilty of causing these deaths. After the execution of a ‘witch’ by Gustav Weil (Peter Cushing) and his Puritan Brotherhood, Weil’s nieces, the twins Maria (Mary Collinson) and Frieda (Madeleine Collinson) Gellhorn arrive in the village of Karnstein, having (following the death of their parents) being left in the care of their aunt Katy Weil (Kathleen Byron) and their uncle Gustav. Upon arriving in the village, Maria and Frieda gaze in wonderment at Count Karnstein’s (Damien Thomas) castle, which overlooks the village. The village, it seems, has been plagued with a number of mysterious deaths: the exsanguinated bodies of young men who have gone missing from the village have been discovered in the surrounding forest. Weil’s Brotherhood have begun executing ‘witches’, who they presume to be somehow guilty of causing these deaths.

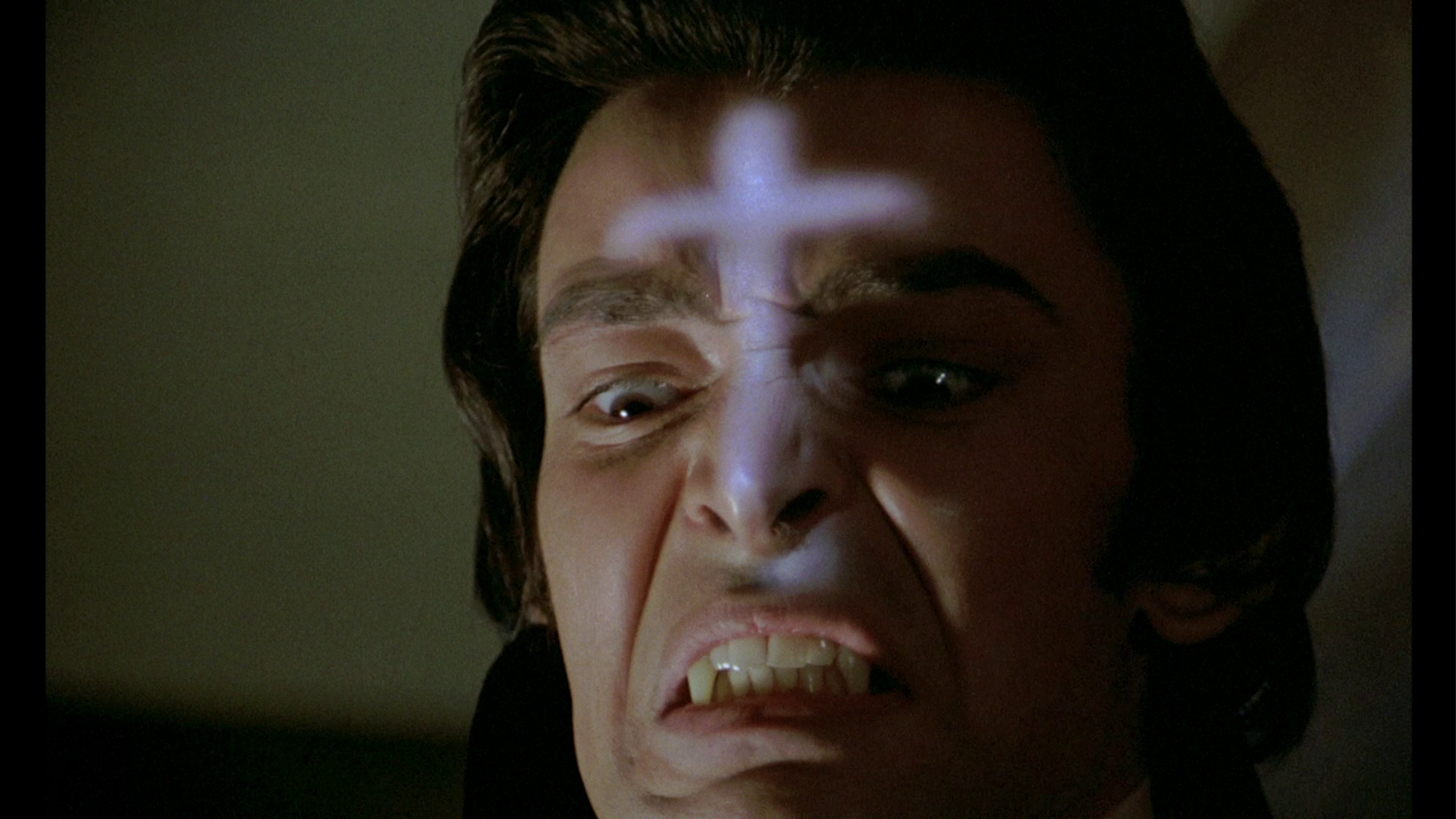

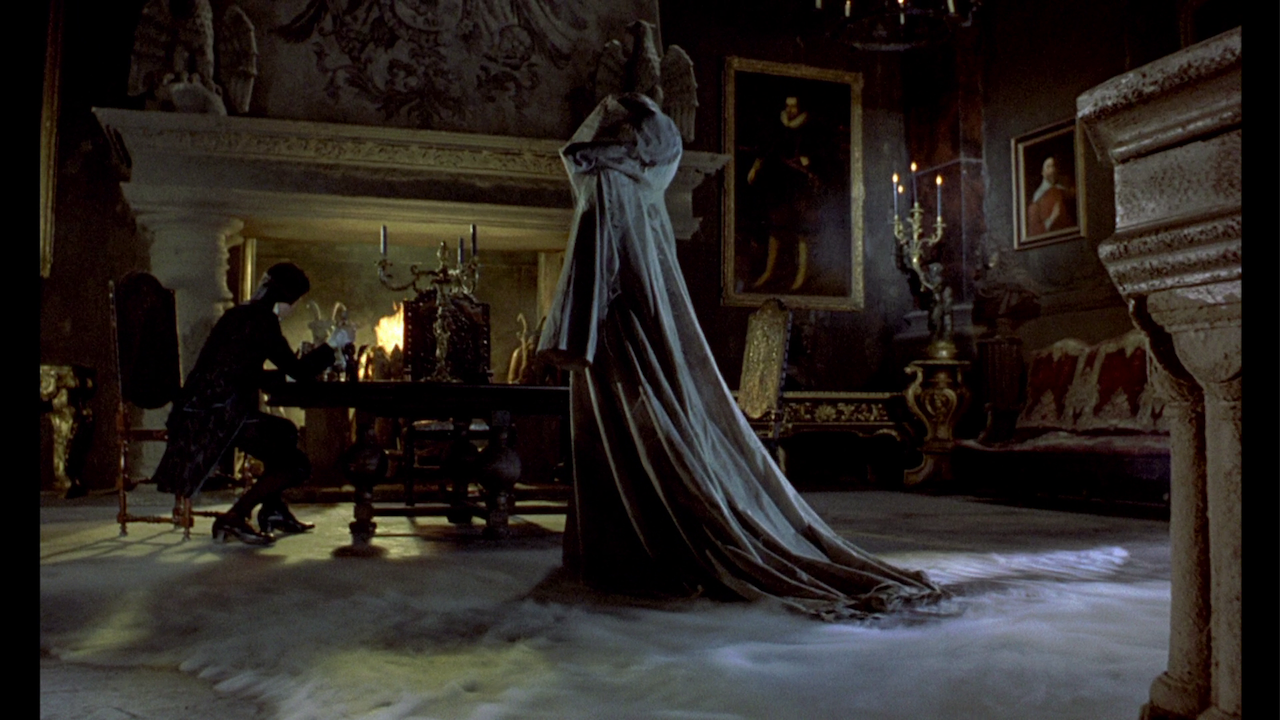

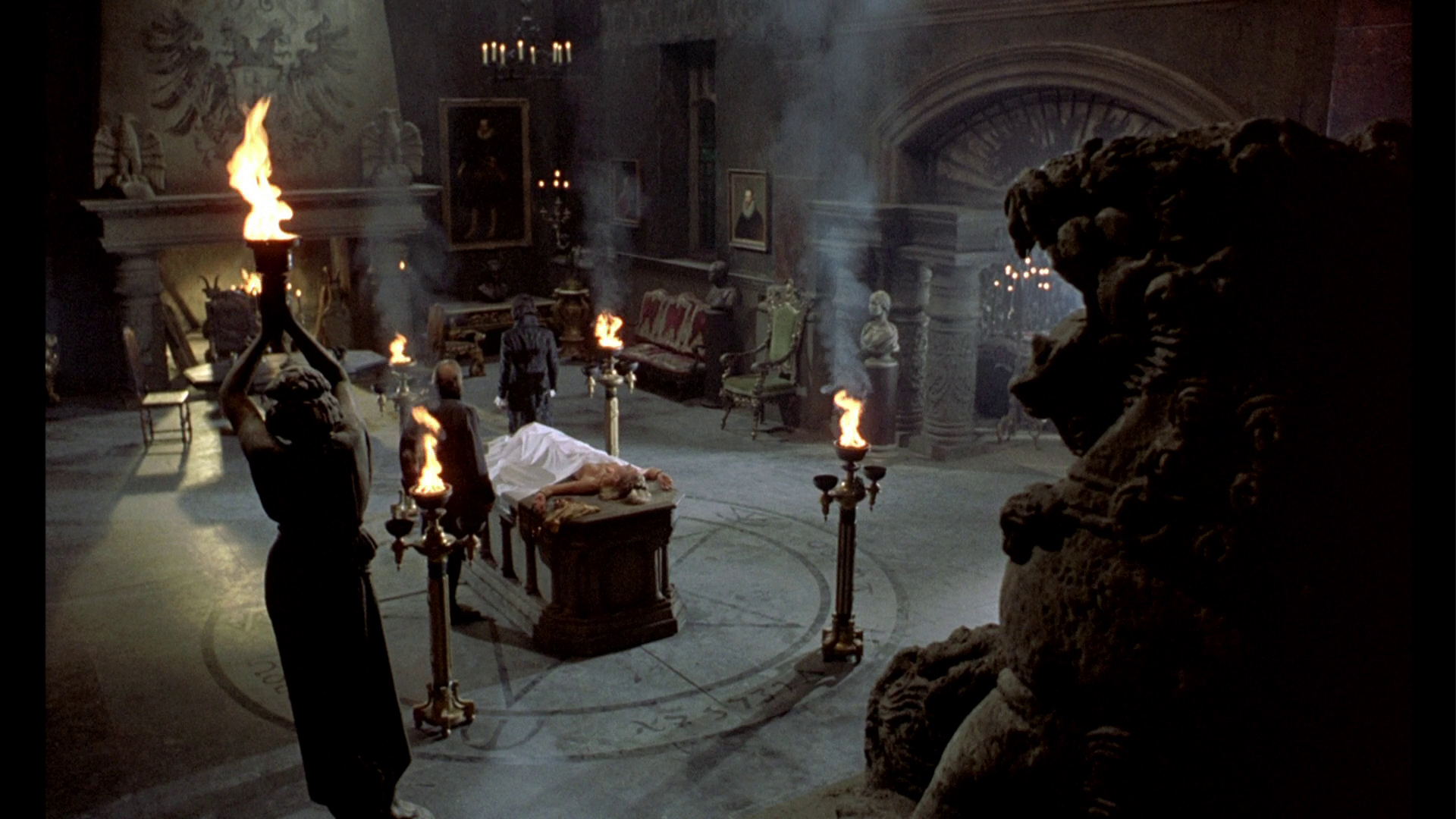

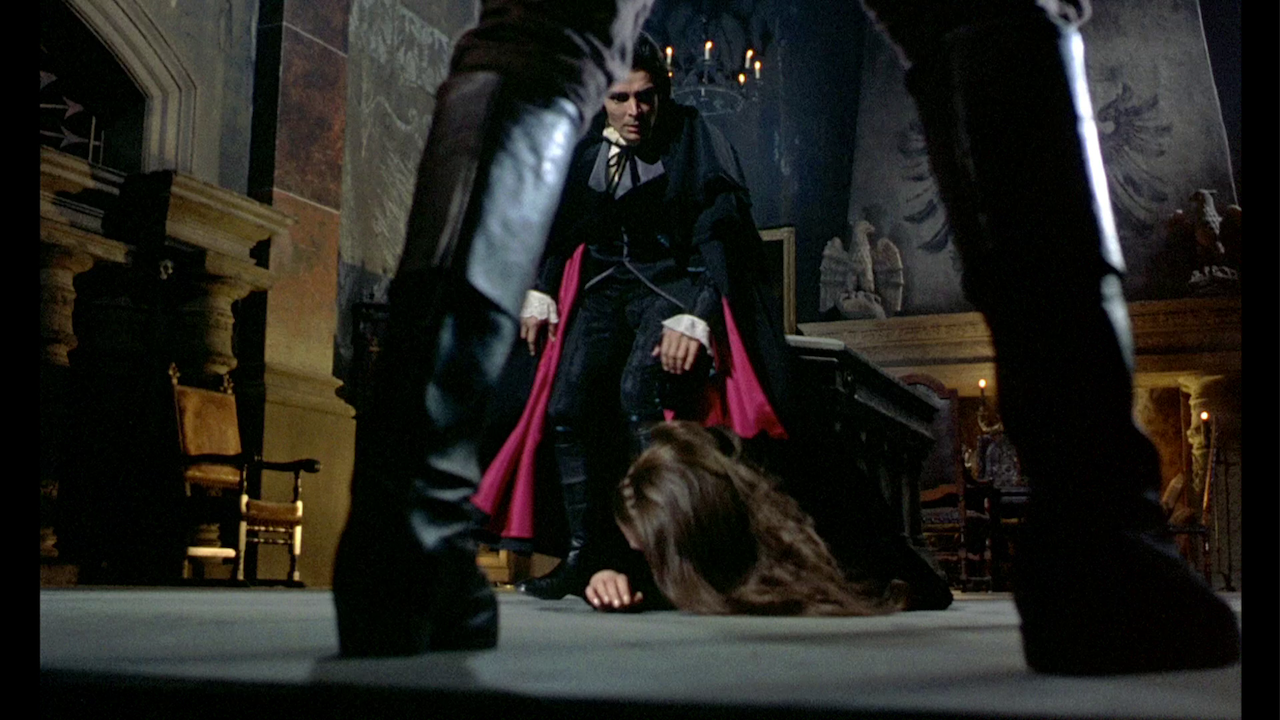

Meanwhile, in the castle, the ennui-ridden Count Karnstein has taken to witnessing Black Masses performed as a kind of Gothic pantomime, in which men in black hoods pretend to execute nubile young women, which are staged for him by his associate Dietrich (Dennis Price). Tired of even this spectacle, Count Karnstein decides to take matters into his own hands and performs a ‘true’ Black Mass of sorts, pledging himself to the Devil before executing a young woman. Shortly after, Karnstein is visited by the spectre of Mircalla, one of his ancestors. Mircalla tells Karnstein she has been sent by the Devil to initiate Karnstein into a life of vampirism. Karnstein submits to this willingly. Visiting the village, Karnstein notices Frieda Gellhorn; Frieda, in turn, notices Karnstein. It isn’t long before Karnstein ‘turns’ Frieda; Frieda’s nightly disappearances are not unnoticed by Gustav, who punishes Maria for her sister’s behaviour. Meanwhile, the Brotherhood’s activities are criticised by Anton (David Warbeck), the village schoolteacher, who is also smitten with Frieda: Anton sees the Brotherhood as superstitious hoodlums, exploiting the villagers’ fear to satiate their own bloodlust. However, when Anton’s sister Ingrid (Isobel Black) becomes a victim of the vampires, he is forced into siding with Gustav against Karnstein.  The film has an incoherence that is slightly frustrating, especially in comparison with, for example, Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968), which throughout its running time maintains a tight focus on the notion that Hopkins’ puritanical crusade is driven by the opportunism of Hopkins (and his assistant Stearne), and facilitated by the unfounded superstitions of the rural communities to which Hopkins and Stearne offer their services as ‘witchfinders’. (Subsequent films modeled on Reeves’ picture, such as Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil, 1970, would muddy these waters somewhat.) In Twins of Evil, the Brotherhood are depicted as Puritan witch-hunters whose desire to ‘punish’ (read: execute) attractive young women who they accuse of Devil worship seems to be an outcome of their sexual repression, representing a desublimation of sexual desire. In the opening sequence, we see them round on a young woman, burning her at the stake. Like the execution of a ‘witch’ by hanging at the start of Reeves’ film, this sequence offers an uneasy spectacle: we see the woman’s agony juxtaposed with the zeal of the members of the Brotherhood, as the men gaze sadistically at the dying woman. In the pre-credits sequence, the Brotherhood arrive at an isolated cabin in the woods. ‘What is it?’, the woman of the house asks. Weil looks on stoically: he doesn’t need to speak. ‘I’m not a witch’, the woman protests. Soon, we see Cushing intoning, ‘O God, have mercy on this poor, unfortunate creature. She is a child of the Devil, but we ask Thee, in Thy great goodness, to spare her soul [….] We commend unto Thee her earthly body and seek to purify its spirit’. As Weil spits out his rhetoric, we see the woman, tied to a stake, burning in a raging fire. The camera juxtaposes her agony with the self-righteous gaze of Weil, and the film’s title appears over a shot of the woman’s face. The film has an incoherence that is slightly frustrating, especially in comparison with, for example, Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968), which throughout its running time maintains a tight focus on the notion that Hopkins’ puritanical crusade is driven by the opportunism of Hopkins (and his assistant Stearne), and facilitated by the unfounded superstitions of the rural communities to which Hopkins and Stearne offer their services as ‘witchfinders’. (Subsequent films modeled on Reeves’ picture, such as Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil, 1970, would muddy these waters somewhat.) In Twins of Evil, the Brotherhood are depicted as Puritan witch-hunters whose desire to ‘punish’ (read: execute) attractive young women who they accuse of Devil worship seems to be an outcome of their sexual repression, representing a desublimation of sexual desire. In the opening sequence, we see them round on a young woman, burning her at the stake. Like the execution of a ‘witch’ by hanging at the start of Reeves’ film, this sequence offers an uneasy spectacle: we see the woman’s agony juxtaposed with the zeal of the members of the Brotherhood, as the men gaze sadistically at the dying woman. In the pre-credits sequence, the Brotherhood arrive at an isolated cabin in the woods. ‘What is it?’, the woman of the house asks. Weil looks on stoically: he doesn’t need to speak. ‘I’m not a witch’, the woman protests. Soon, we see Cushing intoning, ‘O God, have mercy on this poor, unfortunate creature. She is a child of the Devil, but we ask Thee, in Thy great goodness, to spare her soul [….] We commend unto Thee her earthly body and seek to purify its spirit’. As Weil spits out his rhetoric, we see the woman, tied to a stake, burning in a raging fire. The camera juxtaposes her agony with the self-righteous gaze of Weil, and the film’s title appears over a shot of the woman’s face.

At the end of the hanging that opens Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General, presided over by Hopkins (Vincent Price) in the same way that Weil presides over the burning of the ‘witch’ which opens Twins of Evil, the villagers who have watched this grisly spectacle turn and walk away from the scene, apparently disgusted with their bloodlust. By contrast, the Brotherhood’s witnessing of the burning of the young woman seems to strengthen their resolve. Twins of Evil thus suggests in its opening moments that the film will offer a denouncement/critique of the Brotherhood’s superstitious obsession with the concept of Devil worship and its punishment, and the patriarchal cruelty that is evidenced in their brutal treatment of the young women suspected of being Devil worshippers. Furthermore, although the narrative will come to focus on vampirism, this opening sequence and its depiction of the Brotherhood as witch-hunters, suggests that, rather than Hammer’s earlier vampire pictures, Twins of Evil has more in common with the spate of films that, made in the early 1970s, focused on witch-hunting: Mark of the Devil, Blood on Satan’s Claw (Piers Haggard, 1971), Cry of the Banshee (Gordon Hessler, 1970), Ken Russell’s The Devils (1972), and Jess Franco’s Les démons (The Demons, 1973) and Die Liebesbriefe einer portugiesischen Nonne (Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun, 1977). A number of these films, taking their cue from Reeves’ Witchfinder General, question the existence of the supernatural: in contrast, however, Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw reveals the devil to be a very real threat whose existence reinforces the patriarchal authority of Patrick Wymark’s Judge, who proves to be the only person capable of dispatching it. Ian Cooper has stated that in Witchfinder General, ‘[w]hen Matthew Hopkins speaks of “the foul ungodliness of womankind” it reflects his misogyny, be it heartfelt or a calculated pose. But [in Blood on Satan’s Claw] when the Minister […] speaks of the “ungodliness” of the feral village children, it’s very hard to disagree with him’, owing to Haggard’s film’s confirmation of the existence of the supernatural (2014: 91). In contrast with Blood on Satan’s Claw’s exploration of the existence of supernatural phenomena that legitimate the patriarchal authority of the Judge, Jess Franco’s Les démons, on the other hand, shows witchcraft to be a ‘real’ phenomenon that has the revolutionary potential to challenge and undermine a repressive and cruel patriarchal authority (within the film, witchcraft is deployed, at least in part, as a means of righting the wrongs meted out by the witchfinders). At the end of the hanging that opens Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General, presided over by Hopkins (Vincent Price) in the same way that Weil presides over the burning of the ‘witch’ which opens Twins of Evil, the villagers who have watched this grisly spectacle turn and walk away from the scene, apparently disgusted with their bloodlust. By contrast, the Brotherhood’s witnessing of the burning of the young woman seems to strengthen their resolve. Twins of Evil thus suggests in its opening moments that the film will offer a denouncement/critique of the Brotherhood’s superstitious obsession with the concept of Devil worship and its punishment, and the patriarchal cruelty that is evidenced in their brutal treatment of the young women suspected of being Devil worshippers. Furthermore, although the narrative will come to focus on vampirism, this opening sequence and its depiction of the Brotherhood as witch-hunters, suggests that, rather than Hammer’s earlier vampire pictures, Twins of Evil has more in common with the spate of films that, made in the early 1970s, focused on witch-hunting: Mark of the Devil, Blood on Satan’s Claw (Piers Haggard, 1971), Cry of the Banshee (Gordon Hessler, 1970), Ken Russell’s The Devils (1972), and Jess Franco’s Les démons (The Demons, 1973) and Die Liebesbriefe einer portugiesischen Nonne (Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun, 1977). A number of these films, taking their cue from Reeves’ Witchfinder General, question the existence of the supernatural: in contrast, however, Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw reveals the devil to be a very real threat whose existence reinforces the patriarchal authority of Patrick Wymark’s Judge, who proves to be the only person capable of dispatching it. Ian Cooper has stated that in Witchfinder General, ‘[w]hen Matthew Hopkins speaks of “the foul ungodliness of womankind” it reflects his misogyny, be it heartfelt or a calculated pose. But [in Blood on Satan’s Claw] when the Minister […] speaks of the “ungodliness” of the feral village children, it’s very hard to disagree with him’, owing to Haggard’s film’s confirmation of the existence of the supernatural (2014: 91). In contrast with Blood on Satan’s Claw’s exploration of the existence of supernatural phenomena that legitimate the patriarchal authority of the Judge, Jess Franco’s Les démons, on the other hand, shows witchcraft to be a ‘real’ phenomenon that has the revolutionary potential to challenge and undermine a repressive and cruel patriarchal authority (within the film, witchcraft is deployed, at least in part, as a means of righting the wrongs meted out by the witchfinders).

Despite its Witchfinder General-inspired opening sequence, in its confirmation of the supernatural (which occurs later in the narrative, in Karnstein's first encounter with Mircalla) Twins of Evil arguably has more in common with Blood on Satan’s Claw: despite the opening sequence’s suggestion that the film will offer a critique of the Brotherhood’s activities, later sequences show that there is definite evidence around the village of vampirism (the discovery in the forest surrounding the village of exsanguinated corpses with bite marks on their necks). Additionally, the film goes to some lengths to associate vampirism with Devil worship: Karnstein’s blood sacrifice of the young woman is followed by a visit from the ghost of Mircalla, who claims to have been sent by the Devil to initiate Karnstein into a life of vampirism (‘Your body remains on Earth. You will be of the undead [….] We are the undead [….] We walk the Earth, but we exist only in Hell’). As at least some of the bodies are discovered prior to Karnstein’s encounter with Mircalla, it is unclear who is responsible for these acts of vampirism. The film thus suggests that the Brotherhood’s pursuit of vampires/witches/Devil worshippers (within the film's narrative, the three groups are conflated into one) has a justification – and it may even be possible that the women who the Brotherhood punish (by burning them at the stake) are, despite the way in which Hough codes these women as sympathetic through emphasising the brutality of the Brotherhood’s methods, in fact guilty of (or somehow complicit in) these acts of vampirism. Meanwhile, Anton expresses disgust at the Brotherhood’s superstitious crusade, but his offhand comment that decapitation or a stake through the heart are more efficient methods of dealing with vampires than burning is proven to be correct (‘By burning, you char the body. The soul will only recreate itself in another body and continue its carnage’, Anton informs Weil); consequently, he innocently offers the Brotherhood a far more efficient method of ‘dispatching’ their prey – which Anton himself comes to practice at the climax of the film. Despite its Witchfinder General-inspired opening sequence, in its confirmation of the supernatural (which occurs later in the narrative, in Karnstein's first encounter with Mircalla) Twins of Evil arguably has more in common with Blood on Satan’s Claw: despite the opening sequence’s suggestion that the film will offer a critique of the Brotherhood’s activities, later sequences show that there is definite evidence around the village of vampirism (the discovery in the forest surrounding the village of exsanguinated corpses with bite marks on their necks). Additionally, the film goes to some lengths to associate vampirism with Devil worship: Karnstein’s blood sacrifice of the young woman is followed by a visit from the ghost of Mircalla, who claims to have been sent by the Devil to initiate Karnstein into a life of vampirism (‘Your body remains on Earth. You will be of the undead [….] We are the undead [….] We walk the Earth, but we exist only in Hell’). As at least some of the bodies are discovered prior to Karnstein’s encounter with Mircalla, it is unclear who is responsible for these acts of vampirism. The film thus suggests that the Brotherhood’s pursuit of vampires/witches/Devil worshippers (within the film's narrative, the three groups are conflated into one) has a justification – and it may even be possible that the women who the Brotherhood punish (by burning them at the stake) are, despite the way in which Hough codes these women as sympathetic through emphasising the brutality of the Brotherhood’s methods, in fact guilty of (or somehow complicit in) these acts of vampirism. Meanwhile, Anton expresses disgust at the Brotherhood’s superstitious crusade, but his offhand comment that decapitation or a stake through the heart are more efficient methods of dealing with vampires than burning is proven to be correct (‘By burning, you char the body. The soul will only recreate itself in another body and continue its carnage’, Anton informs Weil); consequently, he innocently offers the Brotherhood a far more efficient method of ‘dispatching’ their prey – which Anton himself comes to practice at the climax of the film.

From their arrival in the village, the twins are shocked by the repressive attitudes of the community (and, especially, their uncle), which contrast with their liberal upbringing in Venice. When they first enter their aunt and uncle’s home, aunt Katy tells them to change their clothes: ‘Had you lived in Karnstein, you would still be wearing black’, Katy informs them, referring to the relatively recent death of their parents. ‘We do things differently here’, Katy adds, in a line which is repeated a number of times throughout the film. When Gustav enters the house and notices the way that his nieces are dressed, he declares ‘What kind of plumage is this?’ before asking the girls, ‘Do you know the Fourth Commandment?’ ‘Which one is that?’, Frieda asks, establishing the twins’ naivete towards her aunt and uncle’s profound faith. ‘Honour thy father and thy mother’, Gustav informs the girls, ‘Your parents are not yet cold in their graves’.  Maria and Frieda embody different attitudes towards authority. Whereas Frieda is timid and willing to obey her guardians, Frieda is rebellious and attracted to danger. Frieda is also more observant than her sister: ‘It seems to be everyone’s occupation here, hunting, in one form or another’, she notes during her first meeting with Anton, reflecting on her uncle’s activities with the Brotherhood. ‘Your uncle is misguided, perhaps’, Anton says, ‘but he is a good man’. ‘I don’t like good men’, Frieda tells him in return. Later, she tells Maria, ‘Who wants to be good, if being good is singing hymns and praying all day’; then Frieda is spiteful to her sister, threatening Maria (‘You know what I’ll do to you if you make any trouble’) so as to prevent her from telling Katy or Gustav that Frieda is sneaking out of her room at night. Maria and Frieda embody different attitudes towards authority. Whereas Frieda is timid and willing to obey her guardians, Frieda is rebellious and attracted to danger. Frieda is also more observant than her sister: ‘It seems to be everyone’s occupation here, hunting, in one form or another’, she notes during her first meeting with Anton, reflecting on her uncle’s activities with the Brotherhood. ‘Your uncle is misguided, perhaps’, Anton says, ‘but he is a good man’. ‘I don’t like good men’, Frieda tells him in return. Later, she tells Maria, ‘Who wants to be good, if being good is singing hymns and praying all day’; then Frieda is spiteful to her sister, threatening Maria (‘You know what I’ll do to you if you make any trouble’) so as to prevent her from telling Katy or Gustav that Frieda is sneaking out of her room at night.

William Patrick Day suggests that one of the most interesting aspects of Twins of Evil is Cushing’s performance as the Puritan Gustav Weil: carrying with him the intertextual ‘baggage’ of his performance as Van Helsing in Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1958), in Twins of Evil Cushing represents Hammer’s shifting approach to male authority (which can also be traced in the development of Cushing’s Frankenstein from The Curse of Frankenstein, 1957, to Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, 1974). Where in Fisher’s interpretation of Dracula, Cushing had embodied ‘the rational, humane Van Helsing’, in Twins of Evil Cushing’s ‘crazed’ character is the leader of a group of ‘all-male [Puritan] allies’ who are ‘every bit as frightening as the undead’ (Day, op cit.: 25). Weil, the film suggests, is driven to committing acts of violence against those believed to be vampires (all of whom are attractive, young females) ‘by his own repressed, sadistic sexuality’ (ibid.). In this way, Day argues, Twins of Evil ‘figures repression as a sexual obsession that is the true twin of vampirism’s unbound sexual violence’ (ibid.). Certainly, during one of the Brotherhood’s early meetings, the finger is pointed at a young woman who lives alone in the forest. She falls under suspicion because she ‘refuses to take a husband’. ‘They say she has many husbands’, one of the members of the Brotherhood asserts, referring to the concept of ‘familiars’ but also hinting at sexual promiscuity. (Arriving at the woman’s house, the Brotherhood catch her in flagrante delicto with Count Karnstein, leading to the first stand-off between Karnstein and Weil. Karnstein tells the young woman, ‘Don’t let them [the Brotherhood] bother you. Some men like a musical evening. Weil and his friends find their pleasure through burning innocent girls’.) Shortly after, Frieda and Maria are shown in their bedroom, discussing their aunt and uncle. ‘I know his kind’, Frieda declares, referring to Gustav: she compares him with ‘the men in the park with the funny staring eyes’ that the twins encountered as children, suggesting that she sees Gustav’s repressive Puritanism as a mask for perversion. Frieda goes on to say that ‘He’d love to find us doing something wrong, just to punish us. It would give him a thrill’. Coming so soon after the Brotherhood’s vow to punish a woman who is perceived as promiscuous, this scene seems to consolidate the depiction of the Brotherhood’s activities as offering for the members of the Brotherhood a perverse sadistic thrill, a desublimation of desire.  Delivered with true gusto by Cushing, Gustav Weil’s rhetoric of religious zealotry is chilling. ‘The signs are plain’, Gustav declares during a meeting of the Brotherhood early in the narrative, ‘God is calling on us who believe in His word to stamp out that evil, to seek out the Devil worshippers, and to purify their spirits so that they may find mercy at the seat of the Lord... by burning them!’ The depth of Weil’s rhetoric, and the conviction with which it is delivered, is contrasted in the film with Karnstein’s easy acceptance of Satanism as an ‘out’ for his profound ennui. (Karnstein has much in common with the ennui-ridden villain of Ian Fleming’s novel Live and Let Die: ‘Mr Bond, I suffer from boredom’, Mr Big tells Bond in that novel, ‘I am a prey to what the early Christians called “accidie” – the deadly lethargy that envelops those who are sated'.) Karnstein’s boredom leads him to asking Dietrich to stage theatrical Black Masses within the castle (almost like a bizarre form of performance art, and reminiscent of the ‘staged’ occult ceremonies that appear in Jess Franco’s films of this period). However, bored even with this, Karnstein declares these examples of spectacle to be ‘ridiculous’. Interrupting the ‘performance’, Karnstein asserts, ‘They [his ancestors] knew. They didn’t play at being wicked. They worshipped the Devil and he taught them delights that you will never know – of punishment, inflicting and receiving it; of torture; of death’. Ushering the others from the room, Karnstein then commits a blood sacrifice of the girl who has been involved in the performance of the Black Mass, leading to the visit from Mircalla. At least during the early sequences of the film, Weil’s Brotherhood seem to match (or, arguably, exceed) the cruelty of Karnstein: the villagers represent the human cost of these two fanatical, corruptive ideologies. (In one sequence, Karnstein and Frieda’s torture of a young woman, Greta, is juxtaposed with the Brotherhood’s execution of yet another suspected witch.) Anton embodies the voice of moderation – until, of course, Karnstein’s murder of Anton’s sister Ingrid pulls him into the conflict and, recognising the threat represented by Karnstein, Anton allies himself with Weil. Delivered with true gusto by Cushing, Gustav Weil’s rhetoric of religious zealotry is chilling. ‘The signs are plain’, Gustav declares during a meeting of the Brotherhood early in the narrative, ‘God is calling on us who believe in His word to stamp out that evil, to seek out the Devil worshippers, and to purify their spirits so that they may find mercy at the seat of the Lord... by burning them!’ The depth of Weil’s rhetoric, and the conviction with which it is delivered, is contrasted in the film with Karnstein’s easy acceptance of Satanism as an ‘out’ for his profound ennui. (Karnstein has much in common with the ennui-ridden villain of Ian Fleming’s novel Live and Let Die: ‘Mr Bond, I suffer from boredom’, Mr Big tells Bond in that novel, ‘I am a prey to what the early Christians called “accidie” – the deadly lethargy that envelops those who are sated'.) Karnstein’s boredom leads him to asking Dietrich to stage theatrical Black Masses within the castle (almost like a bizarre form of performance art, and reminiscent of the ‘staged’ occult ceremonies that appear in Jess Franco’s films of this period). However, bored even with this, Karnstein declares these examples of spectacle to be ‘ridiculous’. Interrupting the ‘performance’, Karnstein asserts, ‘They [his ancestors] knew. They didn’t play at being wicked. They worshipped the Devil and he taught them delights that you will never know – of punishment, inflicting and receiving it; of torture; of death’. Ushering the others from the room, Karnstein then commits a blood sacrifice of the girl who has been involved in the performance of the Black Mass, leading to the visit from Mircalla. At least during the early sequences of the film, Weil’s Brotherhood seem to match (or, arguably, exceed) the cruelty of Karnstein: the villagers represent the human cost of these two fanatical, corruptive ideologies. (In one sequence, Karnstein and Frieda’s torture of a young woman, Greta, is juxtaposed with the Brotherhood’s execution of yet another suspected witch.) Anton embodies the voice of moderation – until, of course, Karnstein’s murder of Anton’s sister Ingrid pulls him into the conflict and, recognising the threat represented by Karnstein, Anton allies himself with Weil.

Harry Robinson’s score for the film was composed simultaneously with Robinson’s score for the Elisabeth Bathory-based picture Countess Dracula (Peter Sasdy, 1971), and Robinson has said that ‘themes [in the scores for the two films] kept winging into one another’ (quoted in Huckvale, 2008: 90). Robinson described his music for Twins of Evil as his ‘cowboy score’, in the sense that, like Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General and its focus on Hopkins’ movement through the English landscape on horseback, Twins of Evil’s focus on the horse-riding, witch-hunting ‘Brotherhood’ gives the film the appearance of a curiously Gothic Western (Robinson, quoted in ibid.); and fittingly, Robinson’s score subtly borrows some of the techniques associated with Ennio Morricone’s scores for Sergio Leone’s westerns all’italiana/Italian Westerns, such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Huckvale notes that the film’s main theme, with its galloping rhythm accompanying shots of the Brotherhood on horseback, uses ‘exactly the same phrase structure’ that Morricone used in his score for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966) (ibid.: 96). Reportedly, when Twins of Evil’s producers heard the score for the film, ‘they ran around shooting guns, and they were highly delighted’ (Robinson, quoted in ibid.). Harry Robinson’s score for the film was composed simultaneously with Robinson’s score for the Elisabeth Bathory-based picture Countess Dracula (Peter Sasdy, 1971), and Robinson has said that ‘themes [in the scores for the two films] kept winging into one another’ (quoted in Huckvale, 2008: 90). Robinson described his music for Twins of Evil as his ‘cowboy score’, in the sense that, like Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General and its focus on Hopkins’ movement through the English landscape on horseback, Twins of Evil’s focus on the horse-riding, witch-hunting ‘Brotherhood’ gives the film the appearance of a curiously Gothic Western (Robinson, quoted in ibid.); and fittingly, Robinson’s score subtly borrows some of the techniques associated with Ennio Morricone’s scores for Sergio Leone’s westerns all’italiana/Italian Westerns, such as A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Huckvale notes that the film’s main theme, with its galloping rhythm accompanying shots of the Brotherhood on horseback, uses ‘exactly the same phrase structure’ that Morricone used in his score for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966) (ibid.: 96). Reportedly, when Twins of Evil’s producers heard the score for the film, ‘they ran around shooting guns, and they were highly delighted’ (Robinson, quoted in ibid.).

The film runs for 87:17 mins. Apparently, two fairly minor cuts were made to the film upon its original release (to the scene in which Karnstein is found liaising with a ‘witch’, and to the Black Mass sequence), and these have persisted into all home video versions.

Video

What’s striking about watching Twins of Evil in HD is the prevalence of expressionistic elements within the predominantly studio-bound photography: shots are often set against a background of vivid primary colours, and the enclosed studio sets add to this expressionistic quality. The 1080p image, in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1, is presented in the AVC codec and takes up approximately 16Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc. (By contrast, the presentation of the film on the Blu-ray released by Synapse in the US takes up about 20Gb of space on a dual-layered disc.) What’s striking about watching Twins of Evil in HD is the prevalence of expressionistic elements within the predominantly studio-bound photography: shots are often set against a background of vivid primary colours, and the enclosed studio sets add to this expressionistic quality. The 1080p image, in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1, is presented in the AVC codec and takes up approximately 16Gb of a single-layered Blu-ray disc. (By contrast, the presentation of the film on the Blu-ray released by Synapse in the US takes up about 20Gb of space on a dual-layered disc.)

Detail is strong and, where appropriate, there’s a good sense of depth to the image. Contrast levels are balanced nicely, and the film retains the natural and organic grain structure of 35mm film. The encode seems solid enough too. The presentation of the film on Network’s Blu-ray is comparable to that on Synapse’s release, although Network’s presentation seems to have a more saturated palette – which arguably works in the film’s favour.

Some large screen grabs comparing the Network and Synapse Blu-rays are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel LPCM mono track. This is clean and clear throughout, with a good range (evidenced in the scenes featuring Harry Robinson’s score for the picture). Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc includes the following contextual material: UK Trailer (2:21) US Trailers and Promos (6:12) Deleted Scene (1:09). This scene features two of the girls in Anton’s school singing a ridiculous early-1970s style pop song, ‘True Love’. The song seems designed with the intention of it storming the charts, but it’s utterly out of place and wildly anachronistic. The decision to cut it from the picture was a wise one. Galleries: - Production (11:06) - Behind the Scenes (3:03) - Portrait (1:50) - Promotional (2:54) The titles of these galleries are self-explanatory.

Overall

The confusion of the twins Maria and Frieda threatens to tip the film into farce, and the picture’s depiction of the dualistic relationship between the Weil’s Brotherhood and Karnstein’s vampirism is wildly incoherent. Nevertheless, Twins of Evil has much to commend, including some excellent photography and a haunting/haunted performance from Peter Cushing as Gustav Weil. The presentation of the film on this disc is very good indeed, with a slightly richer palette than the Synapse disc but otherwise pretty much the equal of the US release. However, the US disc contains some additional contextual material. References: Cooper, Ian, 2014: Devil’s Advocates: ‘Witchfinder General’. Columbia University Press Day, William Patrick, 2002: Vampire Legends in Contemporary American Culture. University Press of Kentucky Huckvale, David, 2008: Hammer Film Scores and the Musical Avant-Garde. London: McFarland This review has been kindly sponsored by:  Comparison grabs with the Synapse Blu-ray. In each case, the grab from the Network disc is on top; the grab from the Synapse disc is below it.

Additional grabs from the Network disc:

|

|||||

|