|

The Film

Jim Jarmusch Collection (Soda Pictures), 6 October 2014

Perhaps surprisingly, given his association with the New York independent filmmaking scene, Jim Jarmusch was born in Akron, Ohio. He studied English Literature at Columbio University (in their focus on repetition and their sense of rhythm, Jarmusch’s films are often described as being influenced by his interest in poetry during this period of his life) before, in 1975, visiting the Cinémathèque Française and becoming increasingly fascinated by the possibilities of cinema. Enamoured with the work of directors such as Shohei Imamura, Carl Dreyer, Robert Bresson and Yasujirō Ozu, Jarmusch made the decision to study at New York University’s Graduate Film School, where a key mentor for the young Jarmusch was Nicholas Ray. Ray’s influence on the style of Jarmusch’s features can be seen in the preponderance of night-time scenes and Jarmusch’s sympathy for socially marginalised characters. (A poster for Ray’s 1960 picture The Savage Innocents can be seen in the foyer of the cinema visited by drifter-narrator Allie in Jarmusch’s first film, Permanent Vacation, 1980.)

Jarmusch’s films offer ‘a certain model for independence that combined the conviviality of the French New Wave with some of the down-home brashness of storefront theatre’ (Rosenbaum, 2000: 13). The films offer alternate ethnic points-of-view on life in American cities (New York, Memphis, Los Angeles) and balance experimentation with repetition (ibid.). Several of the films, including Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Permanent Vacation and Dead Man, are all structured around the focus on journeys and movement that forms the thematic backbone of the ‘road movie’.

This Blu-ray boxed set from Soda Pictures collects all six of the pictures Jarmusch made between 1980 and 1995, from his first film Permanent Vacation (1980) to Dead Man (1995). These films include Stranger than Paradise (1984), Down by Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989) and Night on Earth (1992).

Completed in 1980, Permanent Vacation was made for $12,000, with much of the footage shot guerilla-style, without permits, on the streets of New York. The picture has invited comparisons with the films of Jack Rice, Andy Warhol and John Cassavetes. Permanent Vacation is essentially a portrait film, offering a semi-fictionalised account of the experiences of Chris Parker, who plays Allie, with many sequences drawing on Parker’s real-life experiences. Allie is a rootless young man who also narrates the picture. Opening with the juxtaposition of slow-motion shots of crowded city streets with long takes of deserted back alleys, Permanent Vacation establishes New York as a strange space: as, early in the film, Allie is shown wandering through empty streets, empty shops in various states of disrepair in the background, the city takes on the appearance of a post-apocalyptic landscape. (This sequence also establishes the prominent use of graffiti, which features in a number of later Jarmusch pictures: here, Allie walks past the phrase ‘Allie, Total Blamblam’, which is written in large letters with yellow paint on the side of a building.)

Allie’s voice, as the narrator of the picture, contains the characteristics of spontaneous speech (hesitation, repetition), and his opening narration establishes his character as passive/‘easygoing’ and influenced by the jazz ethos. It also foregrounds the episodic structure that will be exhibited within the rest of the film’s narrative. ‘My name is Aloysius Christopher Parker’, Allie tells us in his voiceover, ‘and if I ever have a son he’ll be Charles Christopher Parker, just like Charlie Parker [….] This is my story, or part of it. I don’t expect it to explain all that much, but what’s a story anyway, except one of those connect-the-plots drawings that in the end forms a picture of something? That’s really all this is. That’s how things work for me. I go from this place, this person, to that place or person. And, you know, it doesn’t really make that much difference’. Allie highlights the difficulty of ‘connecting’ with people, stating that, ‘To me, those people I’ve known are like a series of rooms, just like all the places where I’ve spent time’ – as Allie speaks, Jarmusch shows us a series of static shots of rooms: apartments, school rooms, prison cells, a bar – ‘You walk in for the first time, curious about this new room – the lamp, TV, whatever. And then, after a while, the newness is gone, completely. And then there’s this kind of dread, kind of creeping dread [….] And that’s it, time to split’.

Permanent Vacation established many of the leitmotifs that would be consolidated in Jarmusch’s subsequent films: the use of long takes, punctuated by moments of black leader; and a focus on themes of alienation and cultural disconnection, filtered through a narrative that focuses on an outsider who is set adrift within a strange landscape. (‘And so here I am now, in a place where I don’t understand the language’, Allie declares at one point, ‘But strangers are always just strangers’.) In a Jarmusch film, this individual often finds him- or herself in an environment whose cultural iconography is recognisable to them, but they are unable to fully comprehend or come to terms with the context in which this iconography is situated. (For example, set in Memphis and focusing on the iconography associated with Elvis Presley, Mystery Train focus on Japanese, Italian and British characters; Ghost Dog – Way of the Samurai, 1997, offers an alternative perspective on this theme, focusing on an American protagonist who marks himself as a cultural outsider by choosing to live according to the samurai code.)

Another leitmotif within Jarmusch’s work that is established here is the sense of characters talking to one another but not communicating, or delivering monologues to themselves in the guise of dialogue with others. Allie talks to Leila (Leila Gastil), in whose apartment he is a guest. ‘I’m tired of being alone’, Leila asserts. ‘Everyone is alone’, Allie responds, ‘That’s why I just drift, you know [….] Some people, they can distract themselves with ambitions, and motivation to work, you know, but it’s not for me [….] They think people like myself are crazy, you know. Everyone does. Because of the way I live, you know’. As if to reinforce the extent to which Allie is in fact talking to himself, Jarmusch cuts from Leila, who displays not engagement with what Allie is saying, to Allie, who delivers his lines whilst looking out of the window, his back to his presumed listener. Similarly, in Dead Man, when the train fireman (Crispin Glover) speaks to Bill Blake (Johnny Depp) at the start of the film, the passivity of Blake reinforces the sense that the fireman is essentially thinking aloud – especially when the fireman asks if Blake has left behind a wife or fiancée. ‘I had one of those’, Blake replies, ‘but, um, she changed her mind’. ‘She found someone else’, the fireman says, bitterly. ‘No’, Blake protests. ‘Yes she did’, the fireman says, even more bitterly and insistently – clearly reflecting on his own experiences with women.

Like a number of subsequent characters in Jarmusch’s films, Allie is essentially a flâneur in the manner of Walter Benjamin and Baudelaire: ‘The flâneur’s movement creates anachrony: he travels urban space, the space of modernity, but is forever looking to the past. He reverts to his memory of the city and rejects the self-enunciative authority of any technically reproduced image’ (Seale, 2005: np). Allie is a perpetual wanderer/drifter who observes whilst evidencing minimal engagement with their surroundings. At the end of the film, Allie describes himself as ‘just not the kind of person that settles into anything [….] There isn’t really anything left to explain that can be, and that’s what I was trying to explain in the first place [….] I don’t want a job or a house or taxes [….] Let’s just say I’m a certain kind of tourist, a tourist that’s on a permanent vacation’. The phrase ‘a certain kind of tourist’ is applicable to many of Jarmusch’s later characters, including Jun and Mitsuko in Mystery Train, Bob in Down by Law, Eva in Stranger than Paradise, a number of characters in Night on Earth, and Bill Blake in Dead Man.

Completed for $110,000, Jarmusch’s next feature, Stranger than Paradise, began life as an $8,000 short film, ‘The New World’, which was shot in 1982 on monochrome film stock that was left over from Wim Wender’s Der Stande der Dinge (The State of Things, 1982), on which Jarmusch had worked as an assistant. (With Down by Law, Mystery Train, Night on Earth, Dead Man and Ghost Dog, Jarmusch would also work with Wenders’ preferred cinematographer, Robby Muller.) The economic success of Stranger than Paradise, which would gross $1.25 million on its initial release and reach an even wider audience on home video, was an indexical sign of the rise of ‘indie’ cinema during the 1980s. Completed for $110,000, Jarmusch’s next feature, Stranger than Paradise, began life as an $8,000 short film, ‘The New World’, which was shot in 1982 on monochrome film stock that was left over from Wim Wender’s Der Stande der Dinge (The State of Things, 1982), on which Jarmusch had worked as an assistant. (With Down by Law, Mystery Train, Night on Earth, Dead Man and Ghost Dog, Jarmusch would also work with Wenders’ preferred cinematographer, Robby Muller.) The economic success of Stranger than Paradise, which would gross $1.25 million on its initial release and reach an even wider audience on home video, was an indexical sign of the rise of ‘indie’ cinema during the 1980s.

The film is essentially structured around the cultural conflict between Willie (John Lurie) and his cousin Eva (Eszter Balint). Willie is asked by his Aunt Lotte to take care of Eva for a few days, whilst Aunt Lotte is in hospital. Willie’s relationship with Eva is initially troubled, but during the course of her visit they warm to one another, and Willie seems sad when Eva finally returns home to Cleveland, Ohio. A year later, Willie and his friend Eddie (Richard Edson) travel to Cleveland after winning a significant amount of money in a card game. They collect Eva and travel on to Florida for a holiday. However, in Florida Willie and Eddie soon squander the money they have brought with them.

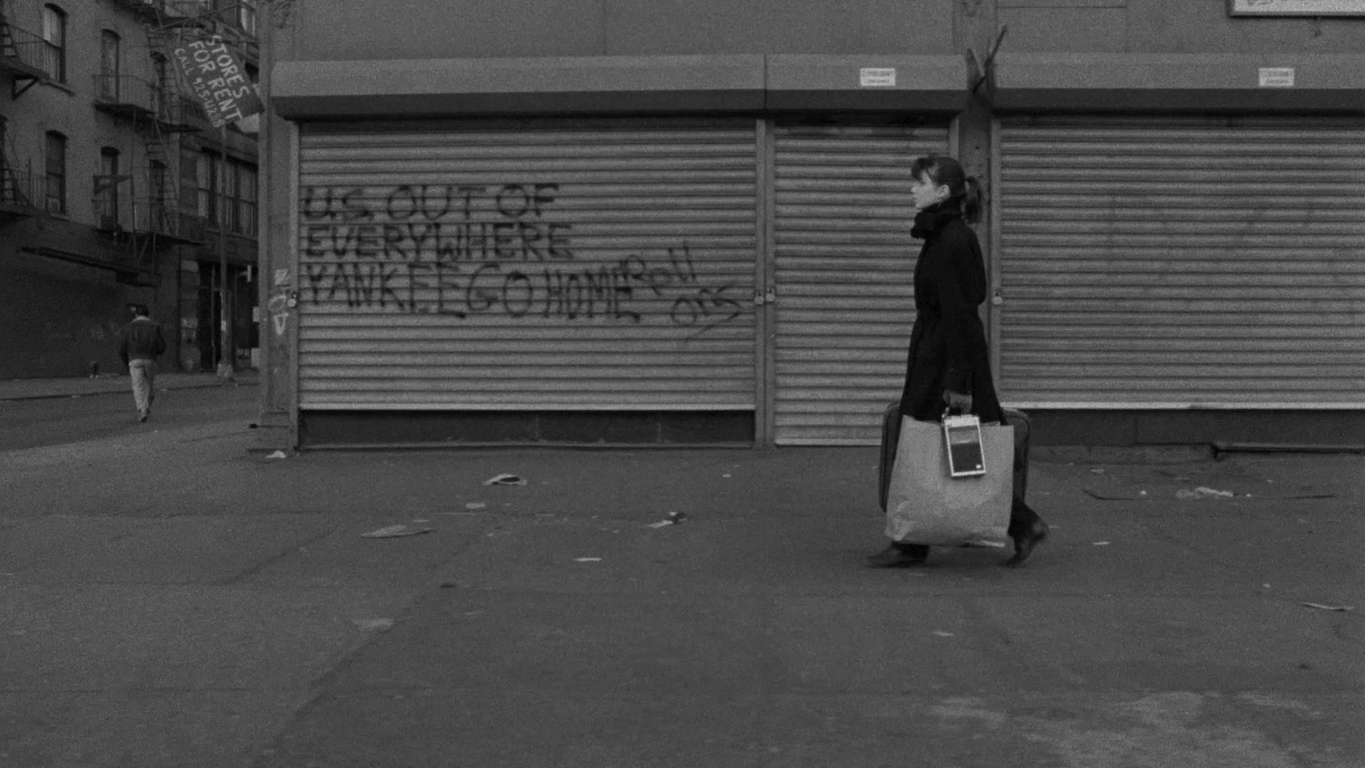

From a Hungarian immigrant family, Willie is fully Americanised, refusing to answer to his Hungarian name (Bela Molnar) and requesting that his relatives speak in English rather than Hungarian (‘Don’t speak to me in Hungarian, please [….] Speak English, please’, Willie tells Lotte when she calls at the start of the film). At one point, Eddie tells Willie, ‘Last year, before I met your cousin [Eva], I never knew you were from Hungary or Budapest or any of those places [….] I thought you were an American’. ‘Hey, I’m as American as you are’, Willie protests. Willie is an outsider to his famly (‘I don’t even consider myself a part of the family. Do you understand?’, he asks Lotte when she tells him he must take care of Eva). Meanwhile, Eva arrives via aeroplane; photographed in monochrome, the landscape is grey and sterile. She wanders through the seemingly deserted city streets (like Allie walking through lower Manhattan at the start of Permanent Vacation), again past Situationist-type graffiti (one example noticeably declares, ‘USA out of everywhere. Yankee go home’), and the US is shot in terms that make it seem to fit the stereotypes of Cold War-era Eastern Europe. The monochrome photography makes the snowbound landscape of Cleveland appear visually indistinguishable from the sun-swept beaches of Florida: both environments seem interchangeable, equally drab and bleak.

The cultural difference between the Americanised Willie and the Hungarian Eva is established in a scene in which Willie eats a television dinner, used as a symbol of a solipsistic society. He asks Eva is she wants one. ‘Why is it called “TV dinner”?’, Eva asks. ‘Um, you’re supposed to eat it while you watch TV’, Willie replies, ‘This is the way we eat in America. I got my meat, I got my potatoes, I got my dessert. I don’t even have to wash my dishes’.

Willie’s home is placed in juxtaposition with Aunt Lotte’s home in Cleveland, where she speaks almost entirely in Hungarian, as Willie and Eddie find when they pay her a visit. However, as in Willie’s apartment, where in long takes Eva and Willie are shown silently watching TV, Willie and Eddie discover that they spend the bulk of their time in Aunt Lotte’s house silently watching the television. When Willie and Eddie play cards with Aunt Lotte, she wins every hand, in an ironic inversion of an earlier scene in which Willie and Eddie are rumbled as cheating by a group of poker players, who notice that the two men win nearly every hand. (‘I am the winner […] I’m lucky at cards. I win every time’, Lotte says in hesitant English. ‘That’s amazing’, observes Eddie.) Willie’s home is placed in juxtaposition with Aunt Lotte’s home in Cleveland, where she speaks almost entirely in Hungarian, as Willie and Eddie find when they pay her a visit. However, as in Willie’s apartment, where in long takes Eva and Willie are shown silently watching TV, Willie and Eddie discover that they spend the bulk of their time in Aunt Lotte’s house silently watching the television. When Willie and Eddie play cards with Aunt Lotte, she wins every hand, in an ironic inversion of an earlier scene in which Willie and Eddie are rumbled as cheating by a group of poker players, who notice that the two men win nearly every hand. (‘I am the winner […] I’m lucky at cards. I win every time’, Lotte says in hesitant English. ‘That’s amazing’, observes Eddie.)

The third feature from Jarmusch, Down by Law features Stranger than Paradise’s John Lurie in a starring role, alongside the Italian comic Roberto Benigni and singer Tom Waits, both of whom would collaborate with Jarmusch a number of times. The film demonstrates a similar fascination with the lives of the pimps, prostitutes and drifters that populate Waits’ songs, two of which open and close the film (‘Jockey Full of Bourbon’ and ‘Tango Till They’re Sore’).

Set in New Orleans and shot for $1 million, the film focuses on Zack (Waits), a radio DJ who is ousted by his girlfriend Laurette (Ellen Barkin) after losing his job and, being offered $1,000 to drive a car across the city, finds himself framed for murder when a body is discovered in the trunk of the vehicle; Jack (Lurie), a pimp who is framed by a rival for liaising with a young girl; and Bob (Benigni), an Italian tourist who accidentally killed a man after being accused of cheating at a card game. These three disparate characters are placed in a jail cell together, but Bob develops a plan of escape, which leads them on a fairy tale-like adventure through the Louisiana swamps.

Each of the three stages of the film (the exposition, depicting Zack and Jack’s lives in New Orleans; the prison sequences; the escape through the swamp) offers a pastiche of a recognisable genre from classical Hollywood cinema: in their night-time setting and high contrast photography, harsh angles and diagonals that cut the screen, the opening sequences offer a pastiche of classic film noir; the prison sequence recalls 1940s prison films such as Jules Dassin’s Brute Force (1947); and the journey through the swamp, which has the texture of a fairy tale, resembles the children’s escape from Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). Each of the three stages of the film (the exposition, depicting Zack and Jack’s lives in New Orleans; the prison sequences; the escape through the swamp) offers a pastiche of a recognisable genre from classical Hollywood cinema: in their night-time setting and high contrast photography, harsh angles and diagonals that cut the screen, the opening sequences offer a pastiche of classic film noir; the prison sequence recalls 1940s prison films such as Jules Dassin’s Brute Force (1947); and the journey through the swamp, which has the texture of a fairy tale, resembles the children’s escape from Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) in Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955).

Down by Law opens with shots that dolly sideways along the streets of New Orleans, shooting the dwellings there dead-on, in the manner of Walker Evans’ iconic Depression-era photographs of the Deep South. We take in shots of a hearse outside a cemetery, rundown houses, people being arrested in the streets – all suggestive of a landscape dominated by death, poverty and criminality. The constant horizontal movement of the camera signifies restlessness and instability, before Jarmusch takes us into the home of Zack and Laurette (where, written on the walls, is the portentous slogan, ‘It’s not the fall that kills you. It’s the sudden stop’); Laurette complains that Zack is too proud to ask for help and has ‘got no fuckin’ future’. (Zack’s response is to assert, ‘Yeah, well, that’s right, Laurette. We can’t live in the present forever’.) Zack takes Laurette’s rant amiable, until she decides to throw his prized shoes out the doorway. ‘Well, I guess we’re through, then’, Zack declares. A parallel argument between Jack and his lover/prostitute Bobbie (Billy Neal) is shown. Bobbie complains that Jack is ‘always blowing it [their money]. You know, gambling, getting high, showing off’. ‘I have to have fun, baby’, Jack tells her. ‘Yeah, yeah, I know. You’re always making big plans for tomorrow. You know why? Cause you’re always fuckin’ up today’, she tells him, adding that, ‘My mama used to say America is a big melting pot. She used to say, when you bring it to the boil, all the scum rises to the top. So maybe there’s hop for you yet, Jack’.

The film has a strong visual style, all long takes, wide-angle lenses and deep focus. The pace is sedate, like Jarmusch’s other pictures containing numerous scenes of the characters reflecting on their fate and talking at (rather than with) one another. Interestingly, Jarmusch chooses to omit what would have been the film’s most conventionally dramatic moment: the prison escape. In cutting from Bob announcing his plan for the escape to the trio of prisoners working their way through the sewers, Jarmusch deliberately bucks Hollywood convention. (‘We have escaped, like in the American movies’, Bob observes.) Throughout the film, solemnity is undercut by absurdity. Bob is the vehicle through which this absurdity is largely communicated. An outsider to American culture, he is nevertheless familiar with aspects of it. He carries with him a handwritten notebook containing popular phrases he has encountered during his time in the country. He displays a familiarity with American poets Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, and can recite their work from memory – but only in Italian (‘I have read only your poets in Italian’, he tells Zack after reciting the Italian translation of Frost’s ‘A Road Less Travelled’). The film has a strong visual style, all long takes, wide-angle lenses and deep focus. The pace is sedate, like Jarmusch’s other pictures containing numerous scenes of the characters reflecting on their fate and talking at (rather than with) one another. Interestingly, Jarmusch chooses to omit what would have been the film’s most conventionally dramatic moment: the prison escape. In cutting from Bob announcing his plan for the escape to the trio of prisoners working their way through the sewers, Jarmusch deliberately bucks Hollywood convention. (‘We have escaped, like in the American movies’, Bob observes.) Throughout the film, solemnity is undercut by absurdity. Bob is the vehicle through which this absurdity is largely communicated. An outsider to American culture, he is nevertheless familiar with aspects of it. He carries with him a handwritten notebook containing popular phrases he has encountered during his time in the country. He displays a familiarity with American poets Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, and can recite their work from memory – but only in Italian (‘I have read only your poets in Italian’, he tells Zack after reciting the Italian translation of Frost’s ‘A Road Less Travelled’).

Jarmusch suggests that the prison that the characters find themselves in is a prison of the mind. ‘I don’t want to deal with you’, Jack tells Zack at one point, ‘As far as I’m concerned, you don’t even exist. ‘Well, you don’t exist either’, Zack responds, ‘ The walls don’t exist, the floor doesn’t exist. This prison’s not here. These bunks aren’t here. The bars aren’t here. None of this is really here. None of this is really here at all’. Later, when Bob has been placed in the same cell as Jack and Zack, he draws a window on the wall of the cell (whilst announcing this in Italian), almost as if this is an act of will. This causes Bob to ask his cellmates if he should say, ‘I look “at” the window’ or ‘I look “out” the window’. Highlighting the fact that the window is nothing more than a drawing on a wall, Jack tells him, ‘Well, Bob, in this case I gotta say, ‘I look at the window’. Later, after they have escaped from the prison, during their journey through the swamp the trio stumble across a shack. ‘Man, this looks a little too familiar’, Jack says as the shack is shown to the audience: it is identical in its layout to the prison cell from which they have just escaped, except that where Bob’s drawn window was in the cell, the shack contains a real window.

Jarmusch’s next picture, Mystery Train, shows a disregard for Hollywood ideas of temporal unity within narratives. Bravely setting aside the notion espoused by Hollywood films since D W Griffith that narrative events occurring in tandem should be presented in parallel, through techniques such as cross-cutting, for example, Mystery Train tells three stories that take place concurrently, but presents them consecutively. It’s a narrative technique that, again defying the conventions of Hollywood storytelling, emphasises repetition. Each of the stories focuses on a displaced foreigner (two Japanese tourists, an recently widowed Italian woman, a British man working in the US) within Memphis, the home of the US’ lasting icon of American, Elvis Presley. The Memphis setting allows Jarmusch to examine the remediation of Presley and the ways in which this icon has been adopted by various groups. Jarmusch’s next picture, Mystery Train, shows a disregard for Hollywood ideas of temporal unity within narratives. Bravely setting aside the notion espoused by Hollywood films since D W Griffith that narrative events occurring in tandem should be presented in parallel, through techniques such as cross-cutting, for example, Mystery Train tells three stories that take place concurrently, but presents them consecutively. It’s a narrative technique that, again defying the conventions of Hollywood storytelling, emphasises repetition. Each of the stories focuses on a displaced foreigner (two Japanese tourists, an recently widowed Italian woman, a British man working in the US) within Memphis, the home of the US’ lasting icon of American, Elvis Presley. The Memphis setting allows Jarmusch to examine the remediation of Presley and the ways in which this icon has been adopted by various groups.

In the first segment, ‘Far From Yokohama’, a young Japanese couple, Jun (Masatoshi Nagase) and Mitsuko (Yûki Kudô), arrive in Memphis by train. On the way, they play paper-scissors-stone to decide which Elvis album (both on cassettes with Japanese writing on the sleeve) to listen to on their walkman. They speak Japanese, Mitsuko observing, ‘It seems like we’ve been on this train forever’. As if to emphasise the strangeness of the landscape in which they find themselves, Jun responds by telling her, in complete seriousness, ‘There’s a time difference in America’.

Memphis, they discover on their arrival, is decidedly unglamorous: the train station at which they alight is plain and rundown. Jun tells Mitsuko, ‘I like Yokohama station better. It’s more modern’, but Mitsuko says she prefers the ‘vintage’ look of the station in Memphis. From the station, they walk along Chaucer Street, the camera shooting them side-on (like Allie in Permanent Vacation and Eva in Stranger than Paradise) as they pass rundown buildings. ‘You know, Memphis does look like Yokohama’, Jun observes, ‘Just more space’. Mitsuko protests that Memphis is nothing like Yokohama: ‘This is America’, she says, and ‘you don’t have Elvis in Japan’.

They take a room in the hotel in which most of the film’s narrative(s) take(s) place, despite struggling to communicate with the night clerk (Screamin’ Jay Hawkins) and bellboy (Cinqué Lee): ‘Good night. Have a nice job’, Mitsuko tells the pair as she and Jun ascend to their room in the hotel. Jun takes photographs of the hotel room. ‘Why do you always take pictures of the rooms that we stay in and not what we see outside when we travel?’, Mitsuko asks him. ‘Those other things are in my memory. The hotel rooms and the airports are the things I’ll forget’, Jun responds.

Each of the rooms in the hotel contains a different portrait of Elvis (each with a different expression on his face). The plethora of reproductions of the image of Elvis is reinforced when Jun takes out her scrapbook, in which she has pasted portraits of Elvis alongside portraits of other important icons: a sculpture of a Middle Eastern king; the Buddha; the Statue of Liberty. All of these icons look uncannily similar to Elvis. ‘He was more influential than I thought’, Jun observes. The segment ends with Jun and Mitsuko hearing a gunshot. ‘Was that a gun?’, Mitsuko asks. ‘Probably. This is America’, Jun tells her.

In the second story, ‘A Ghost’, Nicholetta Braschi plays an Italian woman, Luisa, who has recently lost her husband. The plane carrying her and her husband’s body is waylaid in Memphis, and like the other outsiders in Jarmusch’s filmography Luisa is filmed from the side-on as she walks the streets of the city. She eventually meets a man (Tom Noonan) in a restaurant who cons her out of $20 after telling her a story about meeting the spirit of Elvis in the form of a hitchhiker. In the second story, ‘A Ghost’, Nicholetta Braschi plays an Italian woman, Luisa, who has recently lost her husband. The plane carrying her and her husband’s body is waylaid in Memphis, and like the other outsiders in Jarmusch’s filmography Luisa is filmed from the side-on as she walks the streets of the city. She eventually meets a man (Tom Noonan) in a restaurant who cons her out of $20 after telling her a story about meeting the spirit of Elvis in the form of a hitchhiker.

Luisa eventually finds herself in the same hotel as Jun and Mitsuko, where she shares a room with Dee Dee (Elizabeth Bracco) and sees the ghost of Elvis, who appears to begin to say something profound but then disappears after declaring that he ‘must have got the wrong address or something’. The final segment, ‘Lost in Space’, focuses on Dee Dee’s (now ex-)boyfriend Johnny (Joe Strummer), who along with his friend Will (Rick Aviles) has recently lost his job. Johnny and his newly-acquired gun get into trouble at a bar, and Dee Dee’s brother Charlie (Steve Buscemi), who is under the impression that Johnny is married to Dee Dee, is asked to come and collect him. Johnny, Will and Charlie drive to a liquor store where they encounter a bigoted clerk who makes a racist comment directed towards Will. Johnny shoots the liquor store clerk, and the trio go on the lam, ending up at the hotel: the night clerk there is Will’s brother.

Johnny is nicknamed Elvis by his work colleagues, though he hates the name. Arriving at the hotel and being allowed to hide out in the derelict room 22, Johnny observes the ubiquitous portrait of Elvis. ‘I can’t get rid of that fucking guy’, Johnny says, ‘I mean, shit, why is he everywhere? It’s a black hotel, black neighbourhood, there’s black dudes workin’ on the desk. You know, why don’t they have a portrait of Otis Redding or Martin Luther King?’ ‘That’s cause this is a white-owned hotel’, Will says sensibly, ‘They just got the brothers workin’ here’.

It’s in the hotel that we realise that Will’s surname is Robinson, which leads the bellboy to perform an impression of the robot from Lost in Space (‘Danger, danger, Will Robinson’). The premise of the show, explained to Johnny by Charlie (who asks if the series has never been shown in the UK), acts as an apt metaphor for the experiences of the three groups of cultural outsiders depicted within Mystery Train. ‘That’s how I feel in this place’, Will observes, ‘with you two snowflakes hidin’ in this place: “Lost in Space”’.

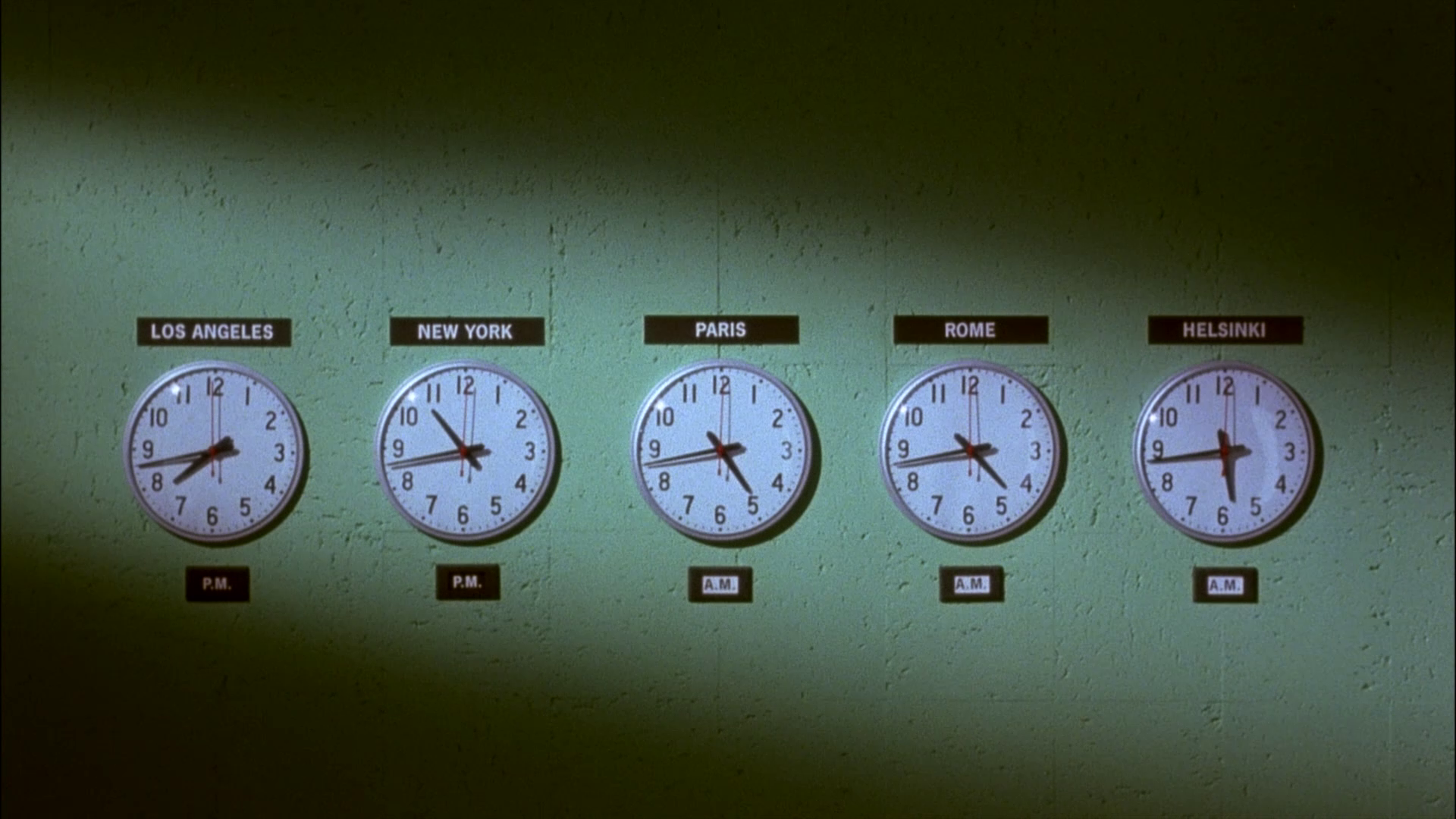

Night on Earth is comprised of five vignettes depicting the meeting of strangers, one of whom is always a taxi driver (in one of five cities: Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome and Helsinki), who converse and then part ways. Each vignette takes place at the same time as the others, but in a different time zone. Like Mystery Train, Night on Earth demonstrates a playful approach to narrative structure and, in particular, the representation of time within film narratives. Night on Earth is comprised of five vignettes depicting the meeting of strangers, one of whom is always a taxi driver (in one of five cities: Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome and Helsinki), who converse and then part ways. Each vignette takes place at the same time as the others, but in a different time zone. Like Mystery Train, Night on Earth demonstrates a playful approach to narrative structure and, in particular, the representation of time within film narratives.

The episodes become increasingly interesting, and increasingly bleak. The first, which features tomboy-ish cab driver Corky (Winona Ryder) transporting a Hollywood casting agent, Victoria Snelling (Gena Rowlands), from the airport, concludes with Rowlands’ character offering Corky a role in a film, but Corky turns it down, assuring the older Snelling (whom Corky addresses as ‘mom’) that she only wants to learn to be a mechanic. The ride is prickly (Rowlands doesn’t like Ryder’s incessant smoking), but when they reach Snelling’s destination the pair part ways with respect for one another – even though they may not comprehend one another’s worldview. (Rowlands’ part in this segment was, apparently, originally written for John Turturro, who was unable to commit to the part; the casting of Rowlands, and then Winona Ryder as Corky, took the segment in a very different direction to what was originally intended.) In the second segment, set in New York, another cab driver – Helmut, a former circus clown from East Germany (Armin Mueller-Stahl) – gives a ride to YoYo (Giancarlo Esposito). Frustrated by Helmut’s inability to drive the cab properly, YoYo takes charge and drives the pair to his destination in Brooklyn, along the way picking up his young sister-in-law Angela (Rosie Perez). Helmut and YoYo are from vastly different cultures and initially struggle to ‘connect’, ridiculing one another’s names, but at the end of the segment they part warmly – though Helmut is left to drive back to Manhattan alone, through a segment of the city that is depicted as cold and threatening. In Paris, a French taxi driver who originally hails from the Ivory Coast (Isaach De Bankolé), is subjected to abuse by two African diplomats who ridicule the very subtle differences between them and him – upon discovering he is from the Ivory Coast, they refer to him as ‘Ivorean’ before labelling him ‘I voir rien’ (‘I see nothing’). Throwing them out of his taxi (‘This is my place of business, not your playground’, he tells them), he then picks up a spiky blind woman (Béatrice Dalle) who resits his attempts to patronise her (‘I don’t need your fucking charity’, she tells him when he tries to lower her fare). Where his previous two passengers were intent on exaggerating the subtle differences between them and him, in order to ridicule the nameless driver, Dalle’s blind woman is completely uninterested in difference (‘I don’t give a fuck about colour’, she tells him when he asks her if she can tell what colour he is by his voice – the concept of ‘colour’ is not part of her perceptual paradigm). The pair display an interest in one another but fail to ‘connect’, and after the blind woman has left the cab at her destination, the driver is involved in a collision which results in the other driver hurling racial abuse at him. In Rome, Gino (Roberto Benigni), picks up a priest (Paolo Bonacelli) and, asserting that he must confess, launches into a blackly comic monologue (based on Benigni’s own comic monologue from 1975, ‘Cioni Mario di Gaspare fu Giulia’) about his sexual experiences (first, with a pumpkin, then with a sheep named Lola, and finally with Monica, his sister-in-law) whilst the priest quietly expires in the back of the cab. Finally, in Helsinki three workers enter the cab of Mika (Matti Pellonpää), telling him that one of their number has had the worst day in his life (he’s lost his job, his car has been wrecked, and his 16 year old daughter is pregnant). Mika ups the ante by telling them the saddest story they will ever hear. Depressed by Mika’s story, the workers find their perceptions of their own experiences changed.

The segments within Night on Earth become progressively bleaker, but also progressively more interesting. The Los Angeles-based story is easily the weakest, but the segment in Paris is fascinating (especially in its focus on prejudice, cultural difference and the exploration of ‘blindness’ as a metaphor), and the Rome episode is incredibly funny (in a very blackly comic manner), thanks in large part to Benigni’s performance. The concept of a journey in a taxi is a motif that fits nicely with the concerns of Jarmusch’s other pictures. The cab functions as a metaphor for the isolation experienced by previous Jarmusch characters like Allie, Eva and Bob: like the flaneur, the vehicle trundles through the urban landscape, the driver and passengers sealed within it, able to observe but not interact with their surroundings. The segments within Night on Earth become progressively bleaker, but also progressively more interesting. The Los Angeles-based story is easily the weakest, but the segment in Paris is fascinating (especially in its focus on prejudice, cultural difference and the exploration of ‘blindness’ as a metaphor), and the Rome episode is incredibly funny (in a very blackly comic manner), thanks in large part to Benigni’s performance. The concept of a journey in a taxi is a motif that fits nicely with the concerns of Jarmusch’s other pictures. The cab functions as a metaphor for the isolation experienced by previous Jarmusch characters like Allie, Eva and Bob: like the flaneur, the vehicle trundles through the urban landscape, the driver and passengers sealed within it, able to observe but not interact with their surroundings.

Since Down by Law, Jarmusch’s films had become increasingly less combative and, despite their playful approach to narrative structure, seemed a little more conventional than the earlier films. As noted by a number of commentators on its original release, in its casting of recognisable ‘stars’ (for example, Winona Ryder), Night on Earth seemed like Jarmusch’s attempt to ‘connect’ with mainstream American cinema without necessarily being absorbed by it. However, with Dead Man Jarmusch constructed an enigmatic film that marked a significant change in Jarmusch’s career: it was his first film with a period setting, exploring the past and its relationship with the present; and the film’s narrative shows an increasing focus on tragedy. The film was based on a project that was initially to have been scripted by Rudy Wurlitzer in 1990. However, Jarmusch and Wurlitzer disagreed over the direction that the project was taking, and the idea was shelved until 1995. The film’s budget was $9 million, and much of this was spent on period details (costumes, props, etc): the decision to shoot in monochrome ate into the budget too, black and white film being more expensive to process. When the film was completed, the distributors, Miramax, delayed its release until 1996, supposedly owing to a disagreement over the final cut: Jarmusch retains control over the editing of his films and refused to cut the two hour-long Dead Man down to a more commercial running time.

The film revolves around Bill Blake (Johnny Depp), an accountant who travels to the town of Machine in search of a job in the metalworks owned by Dickinson (Robert Mitchum). Arriving in Machine, Blake discovers the job vacancy has already been filled, and he seeks solace with a former prostitute, Thel (Mili Avatal). They are interrupted after a night of passion by Thel’s former lover Charlie (Gabriel Byrne). Charlie shoots Thel, also wounding Blake; Blake shoots and kills Charlie. However, Charlie is the son of Dickinson, who hires three gunslingers (Michael Wincott, Lance Henriksen and Eugene Byrd) to track down and kill Blake. Meanwhile, the wounded Blake is rescued and nursed back to health by Nobody (Gary Farmer), a Native American who mistakes Blake for the poet William Blake, with whose poetry Nobody became familiar after being captured by the ‘stupid white man’ and escorted to England, where he was educated in the white man’s schools. The three gunslingers are double-crossed by Dickinson, who also offers a reward to the first person to capture Blake. As Blake and Nobody traverse the landscape, they are followed by the three gunslingers, whose allegiances are increasingly fractured.

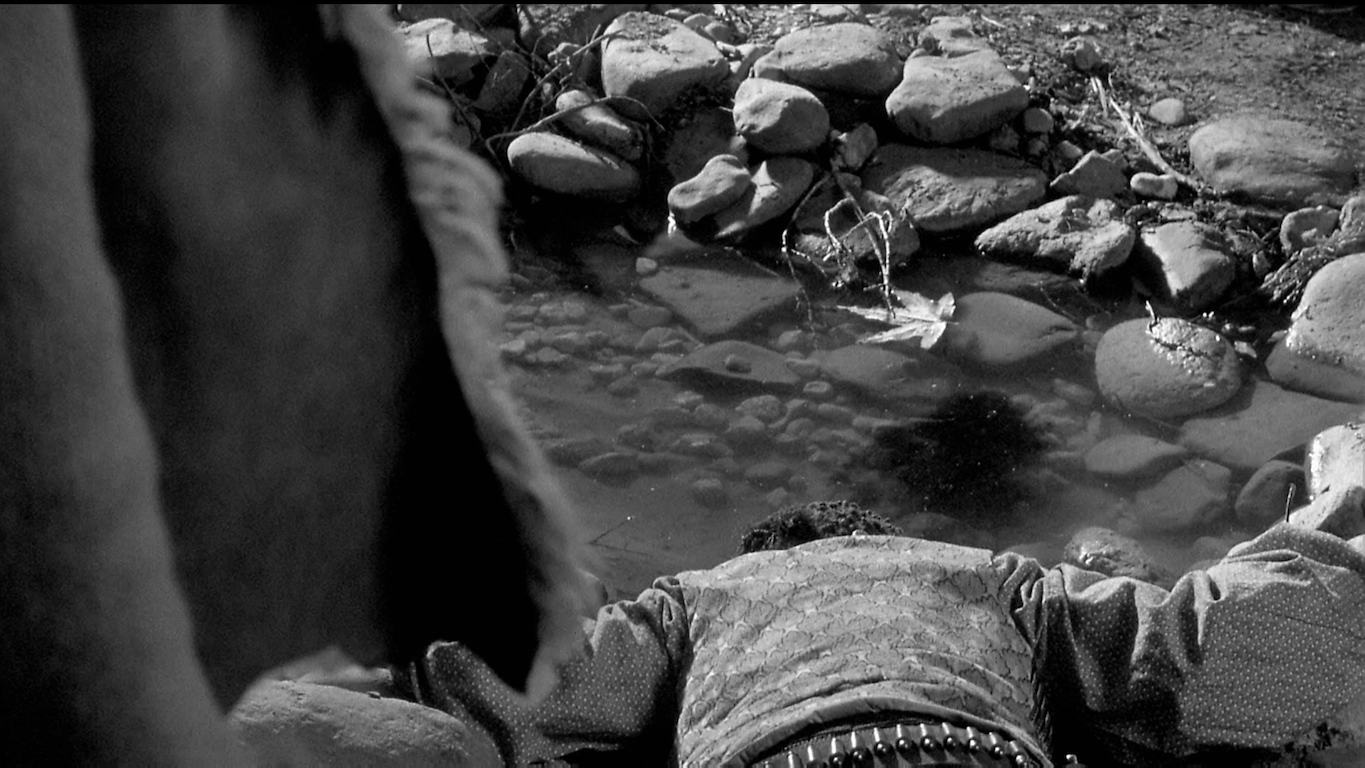

The film has often been labelled as a ‘post-Western’ or ‘anti-Western’, much like Clint Eastwood’s roughly contemporaneous Unforgiven (1992). In his monograph on the film, published in the BFI’s Modern Classics series, Jonathan Rosenbaum suggests the film has many similarities with hallucinatory ‘acid Westerns’ such as El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970) and The Shooting (Monte Hellman, 1966) (op cit.: 49). The film ends with an ironic appropriation of a key paradigm of the American Western, the ‘hero’ riding off into the wilderness (like Alan Ladd at the end of George Stevens’ Shane, 1953). Additionally, the depiction of violence within Dead Man is certainly antithetical to the ways in which violence is usually represented in conventional Westerns, and also represents a challenge to the stylised violence of the Hollywood action film during the 1990s (especially the films that appropriated the balletic violence of Hong Kong’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ pictures): in Dead Man, violence is abrupt, clumsy and pathetic. (Jarmusch would offer his own counterpoint to this in Ghost Dog, which taking its cue from Japanese samurai films depicts violence as graceful.) Jarmusch has said that in the scenes involving gunplay, a ‘gun goes off and guys get hit with metal and fall down like puppets with strings getting cut’ (quoted in ibid.: 39). The film also offers a radical worldview in terms of ‘address[ing] Native American spectators’ and ‘offers one of the ugliest portrayals of white American capitalism to be found in American movies’ (ibid.: 18). The film has often been labelled as a ‘post-Western’ or ‘anti-Western’, much like Clint Eastwood’s roughly contemporaneous Unforgiven (1992). In his monograph on the film, published in the BFI’s Modern Classics series, Jonathan Rosenbaum suggests the film has many similarities with hallucinatory ‘acid Westerns’ such as El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970) and The Shooting (Monte Hellman, 1966) (op cit.: 49). The film ends with an ironic appropriation of a key paradigm of the American Western, the ‘hero’ riding off into the wilderness (like Alan Ladd at the end of George Stevens’ Shane, 1953). Additionally, the depiction of violence within Dead Man is certainly antithetical to the ways in which violence is usually represented in conventional Westerns, and also represents a challenge to the stylised violence of the Hollywood action film during the 1990s (especially the films that appropriated the balletic violence of Hong Kong’s ‘heroic bloodshed’ pictures): in Dead Man, violence is abrupt, clumsy and pathetic. (Jarmusch would offer his own counterpoint to this in Ghost Dog, which taking its cue from Japanese samurai films depicts violence as graceful.) Jarmusch has said that in the scenes involving gunplay, a ‘gun goes off and guys get hit with metal and fall down like puppets with strings getting cut’ (quoted in ibid.: 39). The film also offers a radical worldview in terms of ‘address[ing] Native American spectators’ and ‘offers one of the ugliest portrayals of white American capitalism to be found in American movies’ (ibid.: 18).

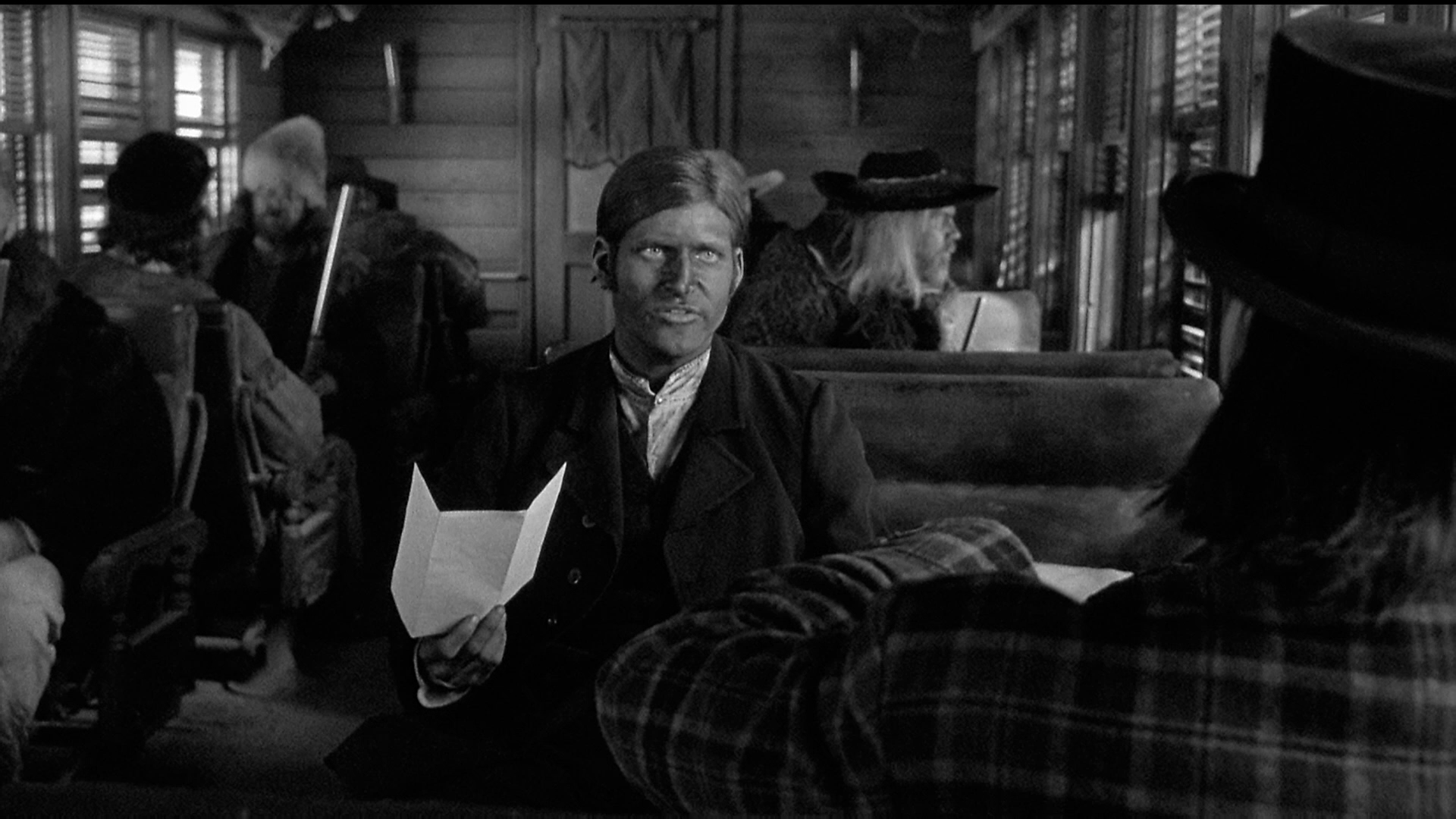

The film’s opening sequence establishes its off-kilter approach to the paradigms of the Western. A train travels through the American countryside, the journey taking just over eight minutes of screen time. The elliptical presentation of the journey (fades in to and out from black) condenses the movement from the civilised ‘garden’ to the Western ‘wilderness’ (to refer to the structuring dualisms of the Western, as outlined in Jim Kitses’ influential study of the genre, Horizons West.) Kent Jones has suggested that the fades to/in from black ‘create an effect of pockets of time cupped from a rushing river of life’ (Rosenbaum, op cit.: 65).

The sequence is highly reminiscent of Jack Carter’s (Michael Caine) movement via train from London to the North of England in Mike Hodges’ Get Carter (1971), where the train’s passage through tunnels gives moments of black screen which condenses the journey and over which the film’s credits (in white lettering) are presented. In Hodges’ film, the train carrying Carter moves north, through an increasingly drab and industrialised landscape, coming to the end of Carter’s journey, in Newcastle. Likewise, Blake’s journey via train takes him through increasingly wilder territory. Outside the window, he sees the landscape change from a cultivated terrain to arid desert, and his fellow passengers become increasingly coarse in their appearance. The fades in to and out of black condense this journey and also signify Blake’s lapses into (and out of) sleep.

At one point, Blake awakens to find the train fireman (Crispin Glover) seated opposite him. The fireman launches into a monologue which offers a prolepsis of the film’s conclusion. Glover’s curious, non-naturalistic line delivery emphasises the strangeness of his monologue and the bizarre shifts in tense, establishing from the outset the ominous overtones of Blake’s journey. Jonathan Rosenbaum has cited this moment as underscoring ‘the inability to distinguish between inner consciousness and external reality’ which informs much of the film (ibid.: 83). At one point, Blake awakens to find the train fireman (Crispin Glover) seated opposite him. The fireman launches into a monologue which offers a prolepsis of the film’s conclusion. Glover’s curious, non-naturalistic line delivery emphasises the strangeness of his monologue and the bizarre shifts in tense, establishing from the outset the ominous overtones of Blake’s journey. Jonathan Rosenbaum has cited this moment as underscoring ‘the inability to distinguish between inner consciousness and external reality’ which informs much of the film (ibid.: 83).

‘Look out the window’, the fireman implores Blake, ‘And doesn’t this remind you of when you are in the boat? And then, later that night, you were lying, looking up at the ceiling, and the water in your hand was not dissimilar from the landscape, and you think to yourself, “Why is it that the landscape is moving, but… the boat is still?’ The fireman compares the terrain to hell, in a foreshadowing of the film’s later references to the apocalyptic work of the poet William Blake: ‘Well, that doesn’t explain why you’ve come all the way out here, all the way out here to hell’, the fireman says. Blake shows him the letter informing of his position in Dickinson’s Metalworks in the town of Machine. ‘I wouldn’t know’, the fireman says, ‘because I don’t read. But I’ll tell you one thing for sure: I wouldn’t trust no words written down on no piece of paper, especially from no “Dickinson” out in the town of machine. You’re just as likely to find your own grave’. The fireman’s speech is punctuated by gunshots. ‘Look, they’re shooting buffalo’, he tells Blake as the other passengers fire rifles out of the windows of train carriage, in an allusion to the mass culling of buffalo that took place during the 1870s as a means of punishing the Native American population (for whom buffalo meat was, obviously, a valuable source of sustenance).

Dead Man is ultimately a fascinating, deeply subversive picture, one of Jarmusch’s best.

NB. Some larger screen grabs from each film are included at the bottom of this review. Screen grabs for Dead Man will be added within the next day.

Video

Each of the films are presented on their own disc within this boxed set. All of the films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Shot on 16mm colour film, Permanent Vacation is presented in its 1.33:1 aspect ratio and takes up approximately 19Gb of disc space. The film has a natural, organic appearance, with a healthy amount of grain for a presentation of a film shot on 16mm. Contrast levels are good, though there seem to be some crushed blacks. There is some very minor wear and tear (white specks).

Stranger than Paradise is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The film was shot on 35mm but on much coarser stock (Eastman 4-X) than Down by Law, for example, which was also shot in monochrome on 35mm. The result, when compared with the presentation of Down by Law included in the same set, is a film that has a stronger, more defined grain structure – almost taking on the texture of a film shot on monochrome 16mm stock, in some sequences. Contrast is excellent throughout, and there’s a strong tonal range, with the mid-tones carried nicely. The image is detailed and has a good sense of depth. It’s a very impressive transfer, taking up almost 21Gb of space on the disc.

Down by Law was also shot in monochrome on 35mm, but as noted above it’s on a more refined stock than Stranger than Paradise and thus has a different texture to that film. Taking up over 19Gb on its disc, Down by Law has an equally organic appearance to the other films included in this set, again thankfully not suffering from any overt digital tinkering. It is also presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. Tones are again good, and the deep focus photography is communicated nicely: the image has a strong sense of depth to it throughout the film. As noted in the comments above, early sequences have the look of film noir (harsh contrast, chiaroscuro lighting, etc), and later sequences have a slightly softer, less ‘contrasty’ appearance – all of which is handled nicely in this presentation.

Mystery Train was shot on 35mm colour stock. The presentation on this film uses the 1.78:1 aspect ratio and is, again, organic and natural-looking. The image is detailed. There’s not so much deep focus photography here (much of the film takes place at night and many scenes are shot with a wide-open aperture), so the image doesn’t have as much ‘depth’ as the presentation of Down by Law – but this is a product of the original photography. Colours (the neon signs on the streets outside the hotel, for example) are vivid. Overall, it’s a very pleasing transfer.

Also shot on 35mm colour film, Night on Earth evidences equally good contrast and colour reproduction, again with a natural grain structure. It’s also in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio. Most of the film takes place in low-light situations, and the presentation on this disc handles this well. The encode takes up 21.5Gb of space.

Dead Man was shot on monochrome 35mm stock, and the presentation here (in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio) has excellent tonal range, noticeable in the scenes in which Blake and Nobody ride through dense foliage. The photography has a strong sense of depth to it, and this is communicated well in this HD presentation. The presentation of the film also has an organic appearance, with a natural level of film grain and no overt, harmful evidence of digital tinkering.

Audio

Audio on Permanent Vacation is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio mono track. It’s a strong audio track, though the audio mix it’s based on is very ‘raw’. Stranger than Paradise is presented in the same format (DTS-HD Master Audio mono) and, again, has a good range and is clear throughout. It’s not a ‘showy’ track by any means, but it comes alive in sequence involving music (eg, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ ‘I Put a Spell on You’): the sound mix on the film is almost as ‘raw’ as that on Permanent Vacation. Down by Law’s audio track, again in DTS-HD Master Audio mono, is far more polished and ‘showy’ than those of the films that precede it in this set, especially in its use of Waits’ songs and John Lurie’s jazzy score. All of these films include optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Mystery Train contains dialogue in English, Japanese and Italian. Again, this track is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio mono mix, with optional English subtitles for the non-English language dialogue – and another optional English HoH subtitles track for the entire film. This audio mix is more polished than that of the preceding films, with a rich soundscape – bookended by two different versions of ‘Mystery Train’ (Presley’s 1955 cover, in the opening sequence, and Junior Parker’s original recording from 1953, over the closing credits). The whistle of the train is a recurring motif on the soundtrack, reinforcing the theme of travel; it’s also abrupt, signalling disturbance and the possibility of movement.

Night on Earth is presented with a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo track, in English, French, Italian and Finnish. Optional English subtitles for the portions of the film presented in non-English languages are present, as are English HoH subtitles for the entire film. The audio track again demonstrates excellent range and is clear throughout.

Dead Man also has a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 sound track. This has a pleasing sense of range to it, evident from the outset with the rumbling of the train accompanied by/complimented through Neil Young’s largely improvised score and, shortly after, the bassy rumblings of the machines in Dickinson’s Metalworks. Optional English HoH subtitles are included.

Extras

All of the discs include a set of Jim Jarmusch trailers for the films released commercially: Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Night on Earth and Dead Man, along with a trailer for Jarmusch’s most recent film, Only Lovers Left Alive.

In addition, Permanent Vacation’s disc includes a documentary, ‘Kino ’84: Jim Jarmusch’ (41:53), which is a reflection of Jarmusch’s career (till that point) that was produced for German television in 1984.

Stranger than Paradise’s disc includes some silent behind-the-scenes 8mm footage shot by Jarmusch’s brother Tom, entitled ‘Some Days in January 1984: A Behind-the-Scenes Super 8 Film by Tom Jarmusch' (15:19).

Down by Law includes outtakes (24:13) from the film and phone calls (audio only, natch) between Jarmusch and Tom Waits (28:43), Roberto Benigni (12:31) and John Lurie (24:17).

Finally, Dead Man includes a batch of deleted scenes (15:38).

Overall

Jarmusch is a fascinating filmmaker, one of the true independents within American cinema. All of the films here are worthy of investigation and serious attention, though Dead Man is arguably his masterpiece – a film I fell in love with when I first saw it at the cinema during its limited release in the UK. Ghost Dog comes close, and it would be great to see that film get a Blu-ray release. Rosenbaum has suggested that Jarmusch’s films, in posing alternatives to capitalism, are characterised by ‘a nostalgie de la boue – a stylistic, existential and bohemian embrace of downscale modes of living’ (Rosenbaum, op cit.: 54). That is probably the best way to sum up these tales of drifters and outsiders. Jarmusch is a fascinating filmmaker, one of the true independents within American cinema. All of the films here are worthy of investigation and serious attention, though Dead Man is arguably his masterpiece – a film I fell in love with when I first saw it at the cinema during its limited release in the UK. Ghost Dog comes close, and it would be great to see that film get a Blu-ray release. Rosenbaum has suggested that Jarmusch’s films, in posing alternatives to capitalism, are characterised by ‘a nostalgie de la boue – a stylistic, existential and bohemian embrace of downscale modes of living’ (Rosenbaum, op cit.: 54). That is probably the best way to sum up these tales of drifters and outsiders.

The presentations of each of the films in this boxed set from Soda Pictures are very impressive. The set also includes some very good contextual material. It’s an arguably indispensible set for any fan of independent filmmaking.

References:

Bernstein, Jonathan, 1992: ‘Taxi Driver’. In: Spin (June, 1992): 62

Hertzberg, Ludvig (ed), 2001: Jim Jarmusch: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi

Rice, Julian, 2012: The Jarmusch Way: Spirituality and Imagination in ‘Dead Man’, ‘Ghost Dog’, and ‘The Limits of Control’. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

Rosenbaum, Jonathan, 2000: BFI Modern Classics: ‘Dead Man’. London: British Film Institute

Seale, Kirsten, 2005: ‘Eye-swiping London: Iain Sinclair, photography and the flâneur’. [Online.] http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/september2005/seale.html

Suarez, Juan Antonio, 2007: Contemporary Film Directors: Jim Jarmusch. University of Illinois

Permanent Vacation

Stranger than Paradise

Down by Law

Mystery Train

Night on Earth

Dead Man

|