|

|

Hawk the Slayer

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (10th July 2015). |

|

The Film

Hawk the Slayer (Terry Marcel, 1980) Hawk the Slayer (Terry Marcel, 1980)

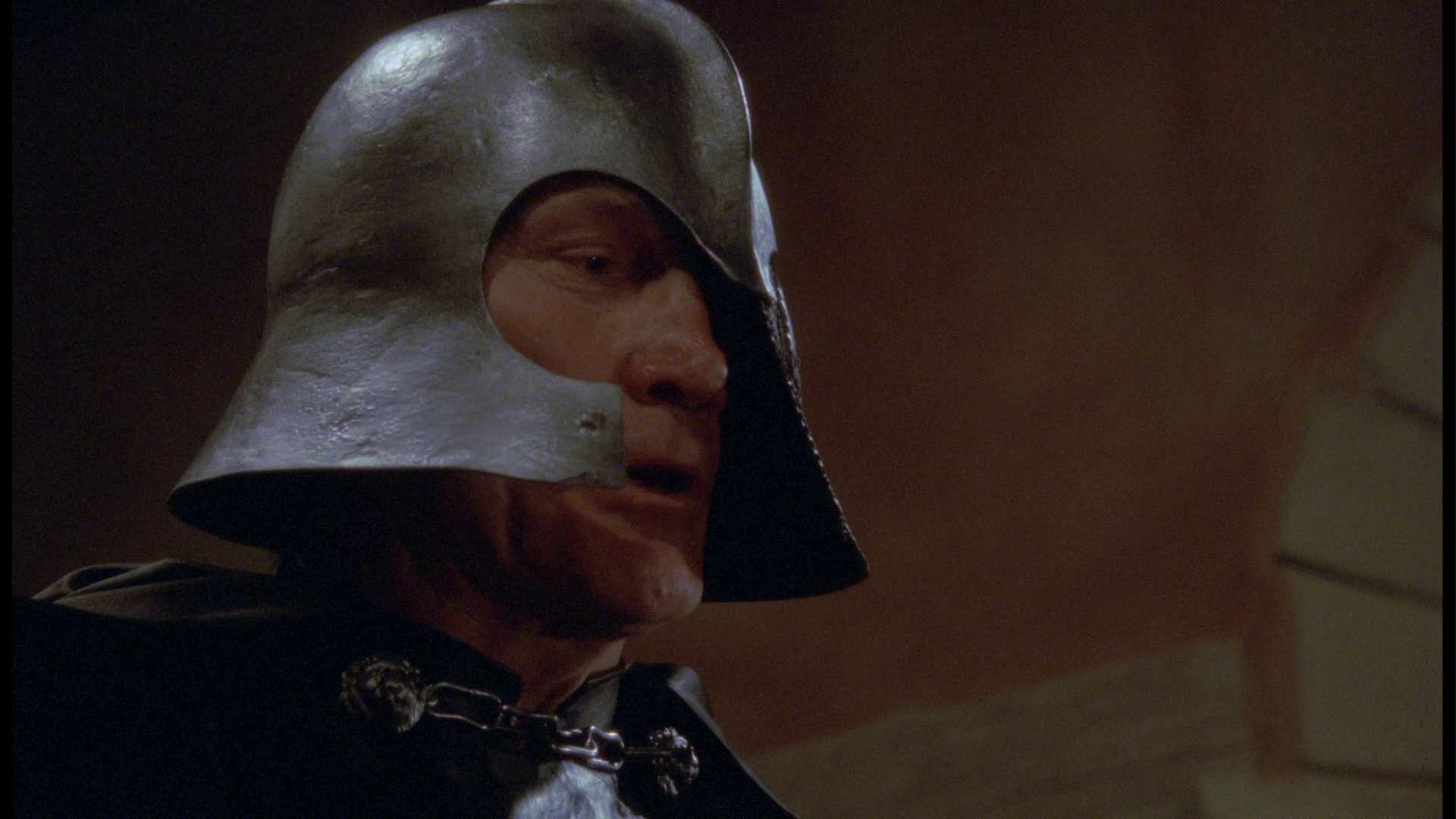

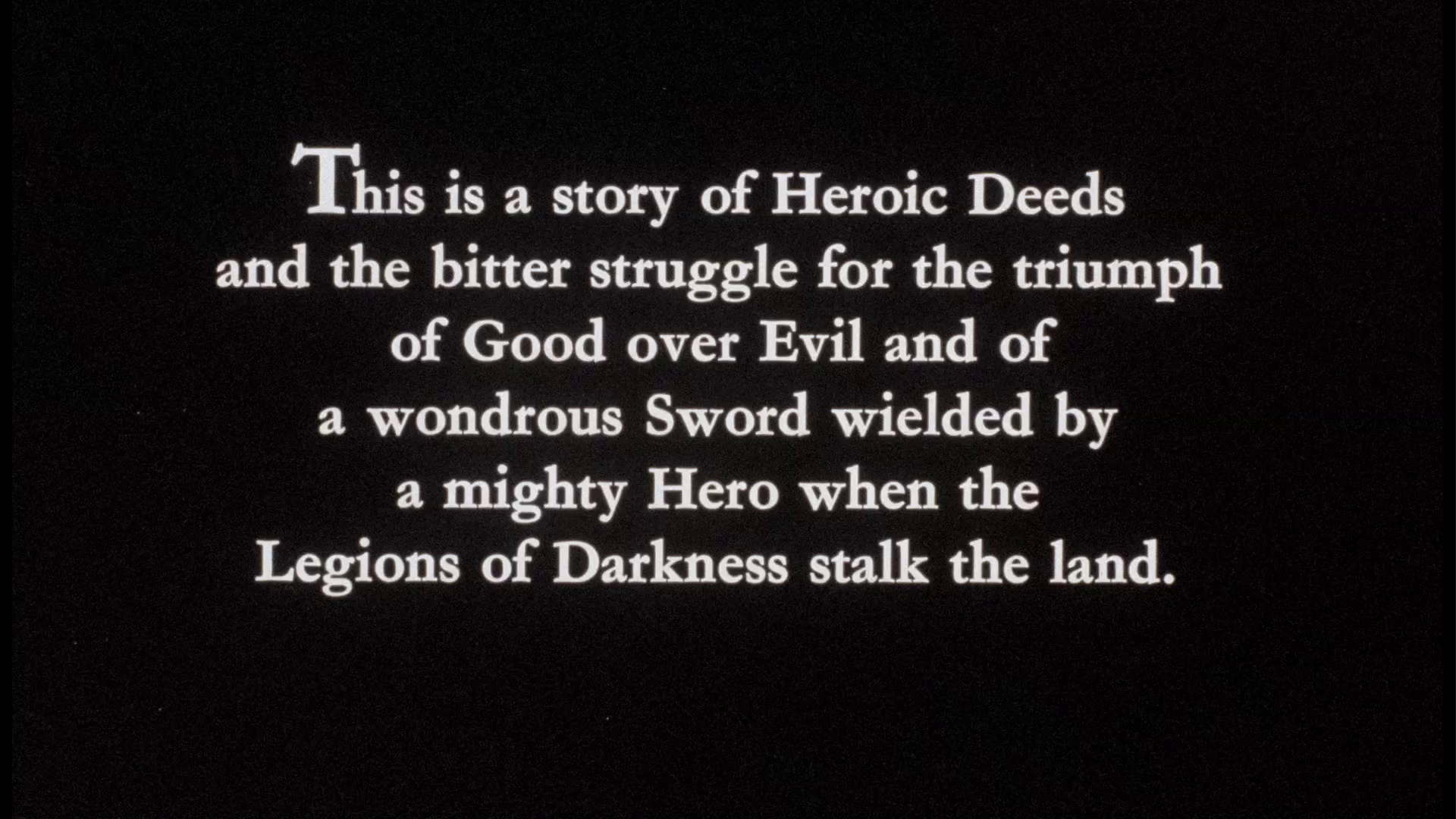

The trend in the early 1980s for ‘sword and sorcery’ films crossed both big Hollywood productions (Desmond Davis’ Clash of the Titans, 1981, and Peter Yates’ Krull, 1983) and smaller independent films (James Sbardellati’s Deathstalker, 1983). During that time, a veritable army of sword and sorcery pictures, with fantastical settings and bizarre creatures, seemed to hit cinemas and the then-new format of videotape. Many of these pictures looked towards classical mythology for their influences (for example, Luigi Cozzi’s Ercole/Hercules, 1983, and its sequel Le avventure dell'incredibile Ercole/The Adventures of Hercules, 1985; Enzo Castellari’s Sinbad of the Seven Seas, 1989); others, such as John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian (1982), were adaptations of more recent texts (in the case of Milius’ film, the stories of Robert E Howard). Conan the Barbarian inspired a significant number of European sword and sorcery films. The Italian pictures that followed in the wake of Conan married influences of the American sword and sorcery films with elements of the pepla/‘sword and sandal’ films (such as the numerous Maciste and Hercules pictures) that were produced in Italy during the 1950s and 1960s: films such as Lucio Fulci’s Conquest (1983), Joe D’Amato’s Ator the Fighting Eagle (1983), Ruggero Deodato’s The Barbarians (1987) and Luigi Cozzi’s Ercole looked as much to 1960s pepla like Roma contro Roma (Rome Against Roma, Giuseppe Vari, 1964) for inspiration as they did to Hollywood models like Clash of the Titans. With their quest narratives and their simplistic modes of combat, the sword and sorcery films of the 1980s often dovetail with the post apocalypse pictures produced during the same era. This tendency is particularly noticeable in some of the Italian pictures such as Enzo Castellari’s I nuovi barbari (The New Barbarians, 1983) but also evident in non-Italian films like Avi Neder’s She (1982). Made in the early years of this boom in sword and sorcery films, Terry Marcel’s Hawk the Slayer (1980) nevertheless feels like a later pastiche of Conan the Barbarian et al. The film opens with a title card which declares (in a particularly ‘wordy’ single sentence that betrays a Lack of Regard for the Distinction between Common Nouns and Proper Nouns): ‘This is the story of Heroic Deeds and the bitter struggle for the triumph of Good over Evil and of a wondrous Sword wielded by a mighty Hero when the Legions of Darkness stalk the land’. Following this we are shown Voltan, the film’s villain, stalking through a fortress. (We know Voltan is the film’s villain because, as per the conventions of the genre, he is helpfully dressed in black, has a facial disfigurement and, most helpfully of all, is played by Jack Palance.) Voltan confronts a man listed in the credits simply as ‘Old Man’ (Ferdy Mayne), the father of both Voltan and the film’s hero, Hawk (the titular slayer, played by John Terry) – this despite the fact that there is only three years difference between the ages of Ferdy Mayne and Palance, and on screen the two actors appear the same age, which might make this scene slightly confusing to a first-time viewer.  Voltan holds a sword to the old man, his father. ‘I demand the key to the ancient power’, he asserts ominously. ‘The ancient power must never fall into the hands of the Devil’s agents’, Voltan’s father declares. ‘Then let the secret die now’, Voltan responds before running his sword through his own parent. Voltan exits and his younger brother Hawk enters, Hawk and Voltan’s father telling Hawk that ‘The prophecy is fulfilled, my son. The evil I have spawned will pollute the land’. However, before he expires, Hawk’s father gives to Hawk his ‘mind sword’: a magical weapon which can be controlled by its owner’s mind. Voltan holds a sword to the old man, his father. ‘I demand the key to the ancient power’, he asserts ominously. ‘The ancient power must never fall into the hands of the Devil’s agents’, Voltan’s father declares. ‘Then let the secret die now’, Voltan responds before running his sword through his own parent. Voltan exits and his younger brother Hawk enters, Hawk and Voltan’s father telling Hawk that ‘The prophecy is fulfilled, my son. The evil I have spawned will pollute the land’. However, before he expires, Hawk’s father gives to Hawk his ‘mind sword’: a magical weapon which can be controlled by its owner’s mind.

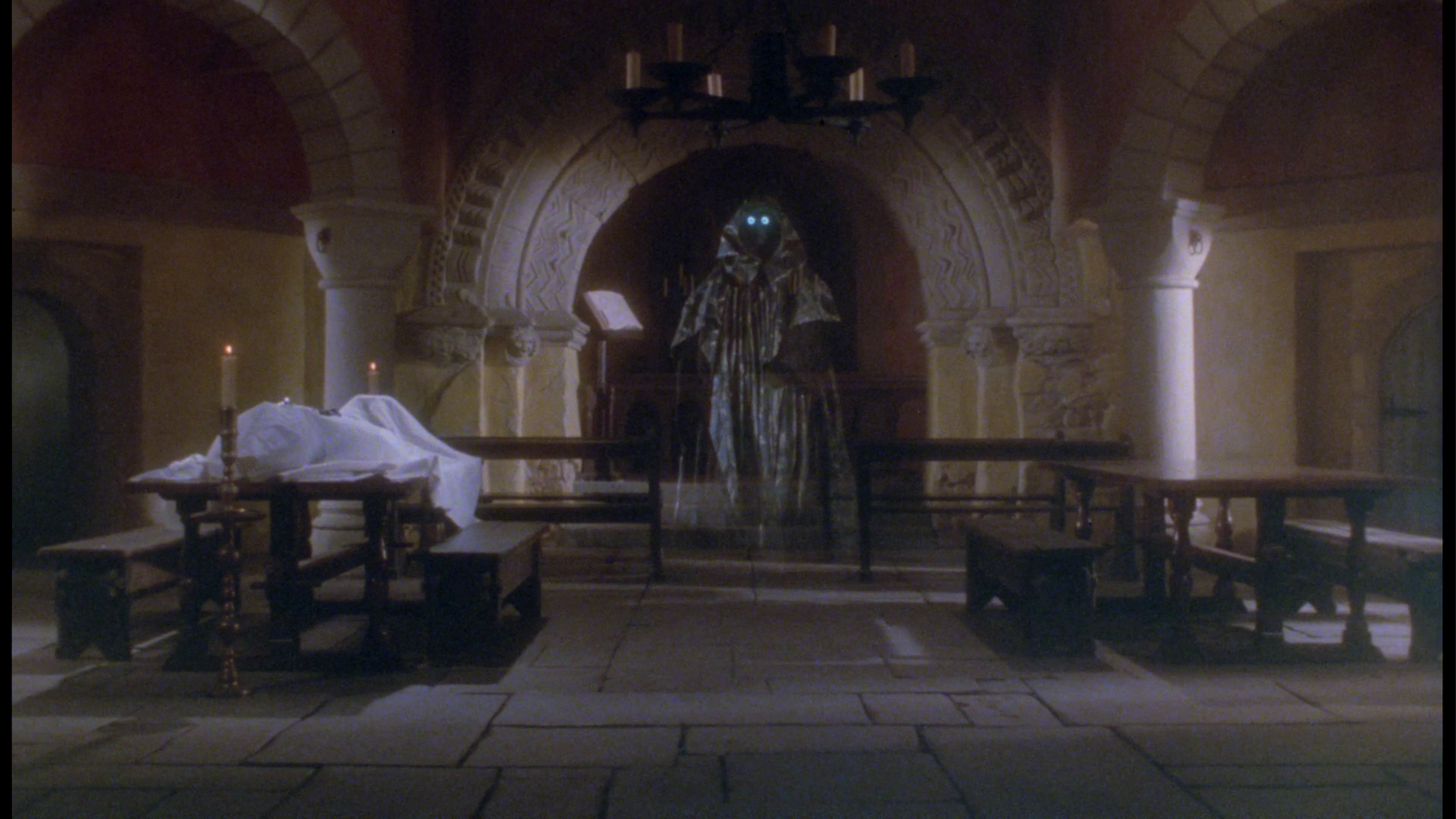

Meanwhile, in another part of the land a wounded man, Ranulf (Morgan Sheppard), escapes a battlefield and is taken in by the Sisterhood of the Holy Ward. They amputate Ranulf’s wounded hand, and Ranulf tells the abbess (Annette Crosbie) of the massacre that took place in his village, instigated by Voltan, in which Ranulf’s family was killed. However, Voltan’s men soon storm the building and abduct the abbess, holding her to ransom and demanding two thousand pieces of gold for her safe return. Ranulf travels to the Holy Fortress to speak with the High Abbott (Harry Andrews). The High Abbott suggests that even if the church could pay the ransom, doing so would simply turn the taking of hostages into a lucrative business for Voltan, putting more members of the church at risk. The High Abbott suggests that Ranulf instead seek the help of Hawk. Elsewhere, Hawk rescues a sorceress (Patricia Quinn) from a band of men who intend to burn her for witchcraft, earning her respect and her promise to help him: ‘You will need me again, for the final battle is yet to be fought’, she tells Hawk. Hawk is united with Ranulf, who tells Hawk of Voltan’s abduction of the abbess. Hawk agrees to help, but he and Ranulf will need further assistance: Hawk proposes to Ranulf that they seek the help of ‘ones [who] are the last of their kind. Gort [Bernard Bresslaw], a giant from the mountains at the edge of the world. Crow [Ray Charleson], an elfin bowman from the Silver Forest, now burnt and blackened. And Baldin [Peter O’Farrell], a dwarf in the Iron Hills’.  The group are advised by the sorceress to steal the gold of Sped (Declan Mulholland), a slave trader who operates on the banks of the River Shale. Hawk intends to use the stolen gold to bargain for the life of the abbess – not necessarily with the intention of giving it to Voltan, but using the gold to lure Voltan into a trap. However, with his adopted son Drogo (Shane Briant), Voltan concocts a plot that is intended to eradicate Hawk and his friends once and for all. The group are advised by the sorceress to steal the gold of Sped (Declan Mulholland), a slave trader who operates on the banks of the River Shale. Hawk intends to use the stolen gold to bargain for the life of the abbess – not necessarily with the intention of giving it to Voltan, but using the gold to lure Voltan into a trap. However, with his adopted son Drogo (Shane Briant), Voltan concocts a plot that is intended to eradicate Hawk and his friends once and for all.

When Hawk is reunited with his old friends Gort, Crow and Baldin, the film takes on the structure of a ‘men on a mission’ film along the lines of Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967) (or perhaps even the model for many of the ‘men on a mission’ films of the 1960s and 1970s, Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, 1954). Before they are brought together by Hawk, we are shown Gort, Crow and Baldin in sequences that show off their respective skills: Gort the giant’s brute strength, Crow the elf’s skill at archery (a rapid-fire technique depicted on screen by the repetition of shots of Crow drawing back his bow and firing), the guile of Baldin. The film seems very heavily influenced by Italian Westerns. Aside from the fact that the sword and sorcery pictures were often structured in a similar manner to Westerns, Hawk the Slayer borrows specific elements from Sergio Leone’s films – in particular, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). When, after the abduction of the abbess, Hawk is shown rescuing a sorceress, his confrontation with the men who are threatening to burn her for witchcraft is prefaced by a shot of Hawk that is accompanied by a short musical ‘sting’ which is incredibly similar to Ennio Morricone’s musical motifs for Blondie (Clint Eastwood) and Sentenza (Lee Van Cleef) in Leone’s film. (The Hard of Hearing subtitles on this disc handily transcribe this piece of music as ‘Oo-ee-oo-ee-oo’.) The standoff between Hawk and the band of thugs is shot and edited like a showdown in one of Leone’s Italian Westerns: a rapid montage of close-ups of faces constructing a three-way standoff like those at the climax of For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. The recurring flashbacks to the roots of the hatred that exist between Hawk and Voltan, each consecutive flashback revealing a little more about this part of the narrative, is also an integral characteristic of Leone’s films, beginning with For a Few Dollars More and appearing in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), Giù la testa (Duck You Sucker, 1971) and the gangster film Once Upon a Time in America (1984).  Throughout Hawk the Slayer, the source for the enmity between Hawk and Voltan is shown via a series of flashbacks. On the day of Hawk’s wedding to Eliane (Catriona MacColl), Voltan confronted the newlyweds: Eliane was Voltan’s beloved, but Voltan’s love for her was unrequited. Voltan blames Hawk for ‘stealing’ Eliane away from him whilst Voltan and their father were fighting battles: ‘While I fought alongside our father’, Voltan tells Hawk, ‘you were here, turning her love for me to hate with your silvery tongue’. (When Voltan tells Hawk, ‘Watch for me in the night’, Eliane observes that Voltan’s ‘mind has turned in on itself’.) Later flashbacks reveal that a power-hungry Voltan shot Hawk with a crossbow bolt, asserting, ‘Once we finish telling our whining, peace-loving father of your death, then he will heed my bidding’. In retaliation for this, Eliane burnt Voltan’s face and, whilst Hawk and Eliane were fleeing, Voltan shot Eliane in the back, killing her. Throughout Hawk the Slayer, the source for the enmity between Hawk and Voltan is shown via a series of flashbacks. On the day of Hawk’s wedding to Eliane (Catriona MacColl), Voltan confronted the newlyweds: Eliane was Voltan’s beloved, but Voltan’s love for her was unrequited. Voltan blames Hawk for ‘stealing’ Eliane away from him whilst Voltan and their father were fighting battles: ‘While I fought alongside our father’, Voltan tells Hawk, ‘you were here, turning her love for me to hate with your silvery tongue’. (When Voltan tells Hawk, ‘Watch for me in the night’, Eliane observes that Voltan’s ‘mind has turned in on itself’.) Later flashbacks reveal that a power-hungry Voltan shot Hawk with a crossbow bolt, asserting, ‘Once we finish telling our whining, peace-loving father of your death, then he will heed my bidding’. In retaliation for this, Eliane burnt Voltan’s face and, whilst Hawk and Eliane were fleeing, Voltan shot Eliane in the back, killing her.

• Throughout the film, Voltan is afflicted by the wound to his face, which he covers with leather armour. The wound causes him near-constant pain which he tries to alleviate by consulting a wizard (Peter Benson). Early in the film, the wizard tells Voltan, ‘Your face does not heal. A strange malady affects the flesh’. The wound which refuses to heal is indexical of Voltan’s evil, a reminder of his cruelty – which as the flashbacks to his murder of Eliane and his attempt on the life of his brother Hawk suggest, predates the wound itself and is an integral part of Voltan’s identity. The wound is also a reminder for Voltan of the betrayal he believes was enacted upon him by Eliane and Hawk. However, Hawk and Voltan’s animosity also hinges on the ill-defined prophecy that is alluded to at several points within the narrative, with the exact role of Hawk and Voltan’s father remaining ambiguous. Voltan’s argument with their father over the ambiguously-defined ‘ancient power’ suggests a context for the private feud between Hawk and his brother which is never fully realised within the film.  Meanwhile, like Voltan’s face, the land itself seems to be scarred by Voltan’s evil. Hawk and Ranulf decide that, to enlist the help of Gort, Crow and Baldin, they must traverse the Forest of Weir. It’s a dangerous journey through a pitch black space. As Hawk and Ranulf ride through the forest, Hawk lights their path with his sword, warning Ranulf that to stray from the light would result in certain death: the green light encircles the pair, and we see beyond its reach cobwebs and brief glimpses of shuffling beasts (puppets, of course) whilst on the audio track we hear ominous screams. ‘The land has changed’, Hawk tells Ranulf. ‘Wolves hunt where there were none before. This was once a green forest filled with sunlight. Now it’s a place of darkness and evil’. Meanwhile, like Voltan’s face, the land itself seems to be scarred by Voltan’s evil. Hawk and Ranulf decide that, to enlist the help of Gort, Crow and Baldin, they must traverse the Forest of Weir. It’s a dangerous journey through a pitch black space. As Hawk and Ranulf ride through the forest, Hawk lights their path with his sword, warning Ranulf that to stray from the light would result in certain death: the green light encircles the pair, and we see beyond its reach cobwebs and brief glimpses of shuffling beasts (puppets, of course) whilst on the audio track we hear ominous screams. ‘The land has changed’, Hawk tells Ranulf. ‘Wolves hunt where there were none before. This was once a green forest filled with sunlight. Now it’s a place of darkness and evil’.

When Voltan and his men abduct the abbess, they demand two thousand pieces of gold for her return. However, the Sisterhood of the Holy Ward is unable to pay this ransom: ‘That is impossible’, one of the nuns declares, ‘The Church has decreed that no ransom should be paid for any of its order. What happens is the will of God’. When Ranulf travels to speak with the High Abbott, he is told that ‘If we pay the ransom for just one of our people, then all of us shall be at risk’. The High Abbott’s words have sense, of course, and offer a sentiment that is later reinforced by Hawk: that paying the ransom will simply encourage Voltan to take more hostages, and will inevitably result in more attacks upon the church. After stealing Sped’s gold, Hawk reveals to the nuns that he intends to use the gold as a trap to lure Voltan. Paying the ransom, Hawk reasons, will not secure the abbess’ life and in fact might achieve the opposite: Hawk suggests that once the gold has been handed over to Voltan, Voltan may very well kill the abbess. However, Sister Monica (Cheryl Campbell) disagrees, arguing that Voltan may be reasoned with.  The debate between Sister Monica and Hawk’s group establishes the pivotal conflict within the film between faith and human agency, a common motif within ‘sword and sorcery’ films generally. Writing from an American perspective, Kevin Flanagan has suggested that 1980s sword and sorcery films ‘embody many of the neoliberalist contradictions that emerged over the course of the 1970s but solidified during the Reagan years: the privileging of unregulated, mercenary agents […] the structural overvaluation of the individual and the small heroic band over any form of widely collective enterprise’ (Flanagan, 2011: 90). ‘The Dark One understands nothing but the spilling of blood’, interjects Ranulf, who has witnessed first-hand the savagery of Voltan and his men, ‘I’m a warrior and I know your salvation from Voltan lies in having the strength of someone like Hawk to protect you’. To this suggestion that the only hope of saving the abbess comes from the human skill of a warrior like Hawk, Sister Monica protests, ‘My son, God protects us’. ‘He was protecting the abbess, and look what happened to her’, Ranulf reminds Sister Monica. ‘Your words flirt with blasphemy’, Sister Monica says in reply. ‘My words are just as true, nevertheless’, Ranulf suggests. Later, Sister Monica protests to Hawk, ‘But he [Voltan] gave his word. We must trust him’. ‘To trust him is to trust the Devil himself’, Hawk informs her. ‘Our sister has great faith in Voltan’s work’, Gort quips dryly. ‘One that she may live to regret’, Hawk suggests. The debate between Sister Monica and Hawk’s group establishes the pivotal conflict within the film between faith and human agency, a common motif within ‘sword and sorcery’ films generally. Writing from an American perspective, Kevin Flanagan has suggested that 1980s sword and sorcery films ‘embody many of the neoliberalist contradictions that emerged over the course of the 1970s but solidified during the Reagan years: the privileging of unregulated, mercenary agents […] the structural overvaluation of the individual and the small heroic band over any form of widely collective enterprise’ (Flanagan, 2011: 90). ‘The Dark One understands nothing but the spilling of blood’, interjects Ranulf, who has witnessed first-hand the savagery of Voltan and his men, ‘I’m a warrior and I know your salvation from Voltan lies in having the strength of someone like Hawk to protect you’. To this suggestion that the only hope of saving the abbess comes from the human skill of a warrior like Hawk, Sister Monica protests, ‘My son, God protects us’. ‘He was protecting the abbess, and look what happened to her’, Ranulf reminds Sister Monica. ‘Your words flirt with blasphemy’, Sister Monica says in reply. ‘My words are just as true, nevertheless’, Ranulf suggests. Later, Sister Monica protests to Hawk, ‘But he [Voltan] gave his word. We must trust him’. ‘To trust him is to trust the Devil himself’, Hawk informs her. ‘Our sister has great faith in Voltan’s work’, Gort quips dryly. ‘One that she may live to regret’, Hawk suggests.

The film achieved a lasting impact amongst fans of the genre, entering the lexicon of ‘geekdom’ to the extent that it was name-checked in an episode of Channel 4’s sitcom Spaced (1999-2001) almost twenty years after its release. In the second episode of series two of Spaced, ‘Change’, Bilbo Bagshot (Bill Bailey) tells Tim (Simon Pegg) that he once punched his father ‘in the face for saying Hawk the Slayer was rubbish’. The film itself has a whiff of camp excess about it and a cult following because of it, and it’s also the subject of many a drinking game; but like many of the sword and sorcery films of this era, Hawk the Slayer possesses an indefinable naïve charm, and this new Blu-ray release will be a nostalgic treat for many of the film’s fans. Hawk the Slayer is presented uncut, with a running time of 93:28 mins.

Video

Using the AVC codec, the 1080p presentation of the film takes up approximately 17Gb of space on a single-layer Blu-ray disc.  The film is presented in what would seem to be the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.75:1. It’s a new transfer based upon the film’s cut negative. The film is presented in what would seem to be the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.75:1. It’s a new transfer based upon the film’s cut negative.

Much of the film was shot with diffused light, most of which seems to be generated through the use of smoke on the film’s set, clearly intended to give the picture an ethereal, otherworldly and dreamlike atmosphere. This was a common element, a paradigm even, of sword and sorcery films of the early 1980s (for other examples, see Fulci’s Conquest or Avi Nesher’s She). Consequently, for much of the film’s running time there’s a hazy softness to the image that is a characteristic of the original photography. That said, even in sequences shot without diffused light there’s often a slight but noticeable softness that suggests some of the finer details have been a little smoothed out through the encode (or perhaps through an ever-so-slightly overzealous application of noise reduction software). Colour consistency is impressive and contrast levels are good too. Detail is strong but sometimes there’s a curious flatness to the presentation, even in sequences staged in depth (eg, the wide-angle shot that shows Hawk approaching the High Abbott for the first time). The natural grain structure of 35mm film is present but again seems slightly muted, possibly owing to the encode not resolving it particularly well. In all, it’s a good presentation of the film, definitely a pleasing one: it’s a decent step above both the DVDs and some of the recent Network Blu-ray releases that have been based on older masters (for example, their recent Blu-ray release of Deadlier Than the Male) but there’s room for further improvement.     NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is a rich track with deep bass and good range. It’s clear throughout and is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- the film’s trailer (2:22). - raw textless elements (2:04). - a vintage episode of Clapper Board, ‘Revenge by the Sword’ (25:48). For those who don’t remember it, Clapper Board was a children’s programme (broadcast on Mondays at teatime) that focused on the world of cinema. It began broadcasting in 1972 (the same year as the BBC’s long-running Film [Insert Year Here] series) and finished in 1982. The series often featured profiles of important people within the filmmaking world but also often featured ‘behind the scenes’ segments showing the production of different films. This instalment of Clapper Board focuses on the production of Hawk the Slayer and offers plenty of behind the scenes footage of the film’s production and interviews with its cast and crew – and reminds the viewer who may have been a child when Clapper Board aired, but a parent today, of how modern children’s television is sorely missing arts-themed programmes that don’t pander to their young audience. - "By the Sword Divided: The Making of Hawk the Slayer" (29:33). This is a compilation of archival interviews with participants in the film’s production. - "Sharpening the Blade: Filming Hawk the Slayer" (15:13). This is a compilation of behind the scenes footage showing the production of the film. - an image gallery (2:17).

Overall

The film places in juxtaposition Sister Monica’s faith, and her naïve belief in Voltan’s ability (or willingness) to keep his word, with the more cynical approach of Hawk’s group, who suggest that human agency is the only thing that will save the abbess and, as Gort puts it, argue that ‘If you’re being stung by wasps, you can either cover your head or you can search out their nest and destroy it’. The film continually reinforces Hawk’s group’s approach, and their refusal to submit to the demands of Voltan, as superior to the capitulative attitude of Sister Monica. It’s a debate that seems to grow naturally out of the wave of politically-motivated kidnappings that took place in the 1970s and which is examined in a number of films of the era, from highbrow 'art' pictures (Costa-Gavras' State of Siege, 1972) to overblown examples of action cinema (Menahen Golan's The Delta Force, 1986). The film places in juxtaposition Sister Monica’s faith, and her naïve belief in Voltan’s ability (or willingness) to keep his word, with the more cynical approach of Hawk’s group, who suggest that human agency is the only thing that will save the abbess and, as Gort puts it, argue that ‘If you’re being stung by wasps, you can either cover your head or you can search out their nest and destroy it’. The film continually reinforces Hawk’s group’s approach, and their refusal to submit to the demands of Voltan, as superior to the capitulative attitude of Sister Monica. It’s a debate that seems to grow naturally out of the wave of politically-motivated kidnappings that took place in the 1970s and which is examined in a number of films of the era, from highbrow 'art' pictures (Costa-Gavras' State of Siege, 1972) to overblown examples of action cinema (Menahen Golan's The Delta Force, 1986).

In terms of its construction, the film owes a great debt to Sergio Leone’s Italian Westerns, but also to ‘men on a mission’ films like Seven Samurai. As in Kurosawa’s film, the wandering ronin¬-like specialists within Hawk’s group have a tendency to wax philosophically about the past. Crow, apparently the last of his race, tells Hawk, ‘Sometimes I tire of the fighting and killing. At night, I can hear the call of my race: they wait for me. When I join them, we will be forgotten’. ‘Your people will never be forgotten’, Hawk assures his friend. The film itself is a cult picture with a certain nostalgic value for its fans. Speaking objectively, it’s far from the best of the films made during the sword and sorcery boom of the early 1980s, but it’s certainly a fun film with a barnstorming performance by Jack Palance. The presentation of the film on this Blu-ray is impressive and a definite improvement over the DVDs. There’s room for improvement, but regardless of this it’s a commendable presentation, especially given the film’s use of diffused light and cheapjack nature, that is sure to please the fans of Hawk the Slayer. The film is accompanied by some very good contextual material, though it’s difficult not to think that a new retrospective documentary on the film’s relationship with the sword and sorcery subgenre, or on its impact on its fans, would have been a nice addition. References: Flanagan, Kevin, 2011: ‘“Civilization … ancient and wicked”: Historicizing the Ideological Field of 1980s Sword and Sandal Films’. In: Cornelius, Michael G (ed), 2011: Of Muscles and Men. North Carolina: McFarland & Company: 87-103 This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|