|

|

Seven Minutes (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th January 2016). |

|

The Film

Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (Russ Meyer, 1970) Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (Russ Meyer, 1970)

Produced with no connection to Twentieth Century Fox’s 1967 film adaptation (directed by Mark Robson) of Jacqueline Susann’s near-iconic 1966 novel Valley of the Dolls, other than its focus on a similar milieu (a group of young women attempting to ‘make it’ in showbusiness) and Fox’s ownership of the title, Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) offers a savage satire of showbusiness and late-1960s counterculture. Drawing on a number of different genres (the melodrama, the horror film, the musical, the sex picture) Meyer’s film is laced with irony, its deliriously ‘meta’ targeting of both Hollywood and its representations and its dry wit underscored by the decision to play its humour ‘straight’, something which reputedly confounded even the actors on the set. (For his part, Meyer supposedly believed that when actors know they’re playing a ‘comic’ part, they very often cease to be funny; see the comments made by Roger Ebert in his commentary on this disc.) After an enigmatic opening titles sequence which depicts events that, the viewer will eventually learn, are contained within the violent climax of the picture, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls opens with a band, the Carrie Nations, playing at a high school prom. The band consists of lead singer Kelly MacNamara (Dolly Read) and her friends Casey (Cynthia Myers) and Petronella ‘Pet’ Danforth (Marcia McBroom). The band is managed by Kelly’s boyfriend Harris Allsworth (David Gurian). After the gig, and desperate to break into the big time, Kelly proposes to the band that they move to Los Angeles and shack up with her ‘rich aunt Susan’ (Phyllis Davis). The sister of Kelly’s mother, Susan owes her wealth to an inheritance from a deceased relative; Kelly’s mother was omitted from the will owing to her status as a ‘black sheep’. Susan proposes giving Kelly a third of her million dollar inheritance, much to the chagrin of Susan’s lawyer Porter Hall (Duncan McLeod).  Susan introduces Kelly to Ronnie ‘Z-Man’ Barzell (John LaZar), arranging for Susan and the band to be invited to one of Z-Man’s parties. There, Kelly is introduced to Ashley St Ives (Edy Williams), star of pornographic films; gigolo Lance Rocke (Michael Blodgett); and Emerson Thorne (Harrison Page). Lured in by the glamour of Los Angeles, Kelly soon ditches Harris in favour of Lance, whilst Harris finds solace in the arms (and bed) of Ashley. Meanwhile, Pet begins to develop an affection for Emerson that is challenged by the intrusion of the musclebound Randy Black (Jim Iglehart), and Casey begins a relationship with Roxanne (Erica Gavin). For his part, Z-Man makes goo-goo eyes at both Harris and Lance. Susan introduces Kelly to Ronnie ‘Z-Man’ Barzell (John LaZar), arranging for Susan and the band to be invited to one of Z-Man’s parties. There, Kelly is introduced to Ashley St Ives (Edy Williams), star of pornographic films; gigolo Lance Rocke (Michael Blodgett); and Emerson Thorne (Harrison Page). Lured in by the glamour of Los Angeles, Kelly soon ditches Harris in favour of Lance, whilst Harris finds solace in the arms (and bed) of Ashley. Meanwhile, Pet begins to develop an affection for Emerson that is challenged by the intrusion of the musclebound Randy Black (Jim Iglehart), and Casey begins a relationship with Roxanne (Erica Gavin). For his part, Z-Man makes goo-goo eyes at both Harris and Lance.

The Carrie Nations’ star is soon in ascendance owing to the patronage of Z-Man, who secures for the band a number of gigs. Egged on by the money-driven Lance, Kelly pesters Susan for a greater share of her money, and ensnares Porter Hall in order to achieve this. Into this world enters Baxter Wolfe (Charles Napier), Susan’s former lover. Having spent some time away from Susan, Wolfe declares his love for her; but is he simply after her money? After coming to blows with Lance over the affections of Kelly, Harris is left out in the proverbial cold, and attempts suicide by throwing himself from the rafters of a television studio where the Carrie Nations are performing. He survives but will spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. Things become even more complicated when Casey reveals that she is pregnant with Harris’ child. The film builds towards it climax in which Z-Man hosts another of his parties: it’s a smaller, more intimate affair, in which Z-Man takes on the persona of Superwoman and invites ‘Jungle Lad’ (Lance Rocke) and ‘Boy Wonder’ (Casey) to join him in the consumption of hallucinogenic substances. When Z-Man makes advances to Lance, Lance ridicules him, sending Z-Man on a murderous rampage.  In the film’s early sequences, upon arriving in Los Angeles and visiting Z-Man’s party, Kelly and her friends are immediately thrown into a maelstrom of exaggerated behaviours and attitudes. The party is populated by eccentrics, including the wonderful and memorably toothless Princess Livingston, who appeared in a number of Meyer’s films beginning with a role as the ‘Scary Woman in Saloon’ in 1962’s Wild Gals of the Naked West. At the party, the topics of conversations involve marijuana, sex, sex changes and pornography… and more sex. In the various rooms, couples make love free from any inhibitions. ‘Feel that, my pretty?’, Z-Man asks Kelly, ‘The night is filled with magic. Mark my words, little dove, tonight is special’. ‘Look there, the famous Ashley St Ives’, Z-Man asserts as Meyer cuts to Edy Williams gyrating sensually, ‘Famous indeed for her portrayals in pornographic pictures. See how she gives her body to the ritual’. With these words, the association of the party with some cabalistic rite is planted in the audience’s mind. Z-Man introduces the ‘cast’ of the party, including Lance Rocke, whose mercenary attitude and exploitation of his own sexuality are foregrounded by Z-Man: ‘See how he [Lance] performs?’, Z-Man asks Kelly, ‘His is a special talent. The golden hair, the bedroom eyes, the firm young body. These are the tools with which he plies his trade. All are available for a price’. Despite Z-Man’s warning, Kelly soon falls under Lance’s spell, leading to the dissolution of her seemingly happy relationship with the less glamorous Harris. Z-Man finishes his introduction to the guests by declaring, in what is perhaps the film’s most famous and frequently quoted line, ‘This is my happening and it freaks me out!’ He tells Kelly that his guests ‘never let me forget all Los Angeles is a jungle’. In the film’s early sequences, upon arriving in Los Angeles and visiting Z-Man’s party, Kelly and her friends are immediately thrown into a maelstrom of exaggerated behaviours and attitudes. The party is populated by eccentrics, including the wonderful and memorably toothless Princess Livingston, who appeared in a number of Meyer’s films beginning with a role as the ‘Scary Woman in Saloon’ in 1962’s Wild Gals of the Naked West. At the party, the topics of conversations involve marijuana, sex, sex changes and pornography… and more sex. In the various rooms, couples make love free from any inhibitions. ‘Feel that, my pretty?’, Z-Man asks Kelly, ‘The night is filled with magic. Mark my words, little dove, tonight is special’. ‘Look there, the famous Ashley St Ives’, Z-Man asserts as Meyer cuts to Edy Williams gyrating sensually, ‘Famous indeed for her portrayals in pornographic pictures. See how she gives her body to the ritual’. With these words, the association of the party with some cabalistic rite is planted in the audience’s mind. Z-Man introduces the ‘cast’ of the party, including Lance Rocke, whose mercenary attitude and exploitation of his own sexuality are foregrounded by Z-Man: ‘See how he [Lance] performs?’, Z-Man asks Kelly, ‘His is a special talent. The golden hair, the bedroom eyes, the firm young body. These are the tools with which he plies his trade. All are available for a price’. Despite Z-Man’s warning, Kelly soon falls under Lance’s spell, leading to the dissolution of her seemingly happy relationship with the less glamorous Harris. Z-Man finishes his introduction to the guests by declaring, in what is perhaps the film’s most famous and frequently quoted line, ‘This is my happening and it freaks me out!’ He tells Kelly that his guests ‘never let me forget all Los Angeles is a jungle’.

With its tongue firmly in its cheek, the film paints a picture of the ways in which the lives of the members of the band, innocent and filled with youthful optimism at the start of the picture, are tainted by their involvement in the world of Z-Man and his cronies: they become swallowed up in a world of drugs, bed-hopping and greed. The first casualty of this encounter is Kelly’s warm relationship with Harris. As the Carrie Nations become increasingly famous, Harris, who during the group’s tenure as a band hired to play high school proms was the Carrie Nations’ manager, finds himself pushed to the sidelines. Feeling like an outsider, he asks Kelly, ‘So where do I fit in? [….] There once was a time that I was your manager, not the next thing to a goddamn groupie’. Kelly soon gravitates towards the bed of the handsome but mercenary Lance Rocke, who with dollar signs clearly in his eyes convinces Kelly that she should press her aunt Susan for a greater share of the inheritance than she has been offered – that Kelly should consider herself entitled to half of Susan’s wealth. (‘There’s no secrets at Z-Man’s’, Lance tells Kelly when she asks him how he knows of aunt Susan’s inheritance.) Shaped by her involvement with Lance, Kelly’s change of character is signaled when Porter Hall demands that she withdraw her interest in Susan’s money. Porter suggests Kelly is a hippie; ‘Come on, man’, Kelly demands, ‘I doubt if you’d recognise a hippie. I’m a capitalist, baby. I work for my living, not suck somebody else’. Returning to Lance, Kelly asks him, ‘Why do I do everything you tell me? [….] I can’t help myself. You’ve made me into a whore’. ‘And you dig it, you little freak’, Lance responds. Later, at another of Z-Man’s parties, Susan sees Kelly and Lance together and says, filled with sympathy for her niece, ‘I hope Kelly knows what she’s getting into. Lance Rocke is no Prince Valiant’. ‘They deserve each other’, Porter Hall responds cruelly.  Meyer pokes fun at the pretensions of Z-Man’s immediate circle of acquaintances. When we first meet Ashley St Aves at his party, we see her talking to some partygoers about her latest ‘controversial box-office blockbuster’, a pornographic film which she declares is about ‘the lack of communication between parent and child’. Harris dismisses this by referring to Ashley’s film as ‘the one about the teenage incest triangle’. In response to this, Ashley tells Harris, ‘You’re a groovy boy. I’d like to strap you on sometime’. Meyer pokes fun at the pretensions of Z-Man’s immediate circle of acquaintances. When we first meet Ashley St Aves at his party, we see her talking to some partygoers about her latest ‘controversial box-office blockbuster’, a pornographic film which she declares is about ‘the lack of communication between parent and child’. Harris dismisses this by referring to Ashley’s film as ‘the one about the teenage incest triangle’. In response to this, Ashley tells Harris, ‘You’re a groovy boy. I’d like to strap you on sometime’.

Against this hotbed of iniquity, ‘squares’ are derided and ostracised. After fucking on the beach with Ashley, Harris seems visibly tired of Ashley’s sexual experimentation and exhibitionism. Standing astride Harris is Ashley, filmed from a low-angle that makes her seem like a giant and gives her a great deal of power. (It’s a composition that recurs throughout Meyer’s body of work – from the low-angle shots of Haji in Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! to the similarly-framed shots of Shari Eubank in Supervixens.) ‘Harris, you’re so square’, Ashley tells him spitefully, ‘You kids are supposed to be swingers [….] What does sex amount to without a sense of guilt? That’s what Sigmund Freud says. Take away the guilt and who’d ever want to get laid?’ Bursting Ashley’s bubble of pretension, Harris hits back: ‘Why, how long’d you lay Sigmund Freud?’ With this, Ashley storms off towards a young man, her new conquest, whilst Harris slopes back to Z-Man’s party where he becomes involved in a fistfight with Lance Rocke over Kelly. Naturally, Lance wins. (‘We could have used you at the Russian Front’, Bormann tells Rocke following the fight.) The sequence in which Roxanne takes Casey, pregnant with Harris’ baby, to an abortion clinic ends with the doctor advancing on Casey whilst she screams – before Meyer cuts ironically to a shot of Pet pouring pancake mix into a pan. In its depiction of the traumatic impact of the act, the characters hitting a sudden wall of responsibility which encourages them to reflect on their hitherto carefree attitudes and behaviours, the sequence might draw associations in the viewer’s mind between this picture and the nightmarish depiction of abortion in Lewis Gilbert’s Alfie (1966). Despite the obvious cultural differences, Meyer’s film has some similarities with Alfie: both feature young characters who are sucked into a life of gleeful hedonism, only to find themselves rushing headlong into a collision with the outcomes of their behaviour. In Alfie, this takes place when the titular lothario (Michael Caine) comes face to face with the aborted foetus and finds himself played at his own game and subjected to the predations of Shelley Winters’ character (who, in modern parlance, would probably be labeled a ‘cougar’). Having lived his life in pursuit of personal gratification, Alfie becomes somewhat cognisant of the impact his behaviour has had on others. In Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, each character has their own epiphany before the final climax, the slaughter at X-Man’s house which deliberately echoes the Tate-LaBianca murders at the hands of Charles Manson’s followers – an even that is often seen as signaling the end of the idealism of the counterculture of the 1960s. At the climax of the picture, Z-Man, Lance and Casey consume a hallucinogenic drug, and the nightmare of violence – initiated by the sexual humiliation directed at Z-Man by Lance – takes place via a visual cacophony of Dutch angle shots and primary colours.  From the outset of the film, authority – especially the authority of middle-aged males – is tied to negative attributes. At the high school prom where the Carrie Nations are first shown performing, a female teacher declares disapprovingly, ‘Disgraceful. Absolutely disgusting’. In response, her male colleague stares lecherously at Kelly and asserts (equally lecherously), ‘I’d like to cut that’. Later, Kelly meets Porter Hall, her aunt’s lawyer, who attempts to put the kibosh on Susan’s plan to gift a third of her inheritance to Kelly – whilst at the same time, he letches after the young woman. Like so many male authority figures in Meyer’s films, Porter Hall is both a sleazy lecher and an agent of repression, preventing women from acting on their will. At Z-Man’s party, Porter converses with Casey. ‘I make it a point never to miss one of Ronnie’s parties. Better than the zoo’, he says cruelly. ‘Are you putting people down for having a good time?’, Casey asks him in response. ‘On the contrary, my dear’, Porter says, ‘But I must confess: this is hardly my idea of a good time’. When Casey reveals herself to be the daughter of a senator, Porter declares snidely, ‘I’ll bet he’s highly amused that his daughter’s a hippie’. ‘I’m in a rock group’, Casey corrects him. ‘And that’s your uniform?’, Porter sneers. ‘And that’s yours?’, Casey fires back at him, referring to his tuxedo. ‘At least it’s not a uniform worn by freaks’, Porter asserts spitefully. From the outset of the film, authority – especially the authority of middle-aged males – is tied to negative attributes. At the high school prom where the Carrie Nations are first shown performing, a female teacher declares disapprovingly, ‘Disgraceful. Absolutely disgusting’. In response, her male colleague stares lecherously at Kelly and asserts (equally lecherously), ‘I’d like to cut that’. Later, Kelly meets Porter Hall, her aunt’s lawyer, who attempts to put the kibosh on Susan’s plan to gift a third of her inheritance to Kelly – whilst at the same time, he letches after the young woman. Like so many male authority figures in Meyer’s films, Porter Hall is both a sleazy lecher and an agent of repression, preventing women from acting on their will. At Z-Man’s party, Porter converses with Casey. ‘I make it a point never to miss one of Ronnie’s parties. Better than the zoo’, he says cruelly. ‘Are you putting people down for having a good time?’, Casey asks him in response. ‘On the contrary, my dear’, Porter says, ‘But I must confess: this is hardly my idea of a good time’. When Casey reveals herself to be the daughter of a senator, Porter declares snidely, ‘I’ll bet he’s highly amused that his daughter’s a hippie’. ‘I’m in a rock group’, Casey corrects him. ‘And that’s your uniform?’, Porter sneers. ‘And that’s yours?’, Casey fires back at him, referring to his tuxedo. ‘At least it’s not a uniform worn by freaks’, Porter asserts spitefully.

Meyer connects these forces of repression with Nazism by, as in a number of his films, including fugitive Nazi Martin Bormann (Henry Rowland) as a character. Here, Bormann is an employee of Z-Man, serving drinks at Z-Man’s parties. Bormann also appears in Meyer’s Supervixens (1975), as the owner of the gas station where the film’s protagonist Clint Ramsey works, and in Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens (1979). In Meyer’s The Seven Minutes (1971), Bormann is again allied to the forces of repression by being included as the butler of one of the men involved in the cynical conspiracy to prosecute the novel The Seven Minutes as obscene, solely in order to bolster the political aspirations of the District Attorney. Here, in Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Bormann is dispatched brutally by Z-Man, who at the tideline on the beach runs a sword through the ageing Nazi whilst mocking him (‘You beg for mercy while the cries of six million innocents ring in your ears? They are waiting for you!’).  The pace of the picture’s editing is often rapid, some sequences appropriating the montage aesthetic of the wartime newsreels for which Meyer would have contributed footage during his tenure as a combat cameraman, and the post-war industrial films that Meyer also made. As Kelly proposes, offscreen, to her bandmates that they move to Los Angeles, Meyer presents us with a dazzling array of images, some of them flashforwards or moments of prolepsis to later scenes (and some of them not): shots of the city skyline, parties, couples having sex, eccentric characters. This montage is accompanied by a voiceover: Kelly and Harris offering back and forth rhyming couplets about the city that is their destination (‘Perverts. Fruits’, Harris declares; ‘Swingers. Kooks’, Kelly responds). Following Z-Man’s explosion of brutal violence, the picture ends with a deeply ironic voiceover narration which highlights the moral flaws of the various characters and tells the audience ‘You must each decide what your life will be’, offering a plea for ‘love that asks nothing, expects nothing. It is simply there’. The pace of the picture’s editing is often rapid, some sequences appropriating the montage aesthetic of the wartime newsreels for which Meyer would have contributed footage during his tenure as a combat cameraman, and the post-war industrial films that Meyer also made. As Kelly proposes, offscreen, to her bandmates that they move to Los Angeles, Meyer presents us with a dazzling array of images, some of them flashforwards or moments of prolepsis to later scenes (and some of them not): shots of the city skyline, parties, couples having sex, eccentric characters. This montage is accompanied by a voiceover: Kelly and Harris offering back and forth rhyming couplets about the city that is their destination (‘Perverts. Fruits’, Harris declares; ‘Swingers. Kooks’, Kelly responds). Following Z-Man’s explosion of brutal violence, the picture ends with a deeply ironic voiceover narration which highlights the moral flaws of the various characters and tells the audience ‘You must each decide what your life will be’, offering a plea for ‘love that asks nothing, expects nothing. It is simply there’.

Jacqueline Susann’s novel Valley of the Dolls became indexical of mid/late-1960s disposable pop culture, to the extent that it’s referenced as such in a wonderful sequence from Roger Corman’s 1970 counterculture film Gas-s-s-s (recently released on a wonderful Blu-ray from Signal One Entertainment: see our review here). Corman’s picture features two young characters, Coel and Cilla (Robert Corff and Elaine Giftos), in a post-apocalyptic landscape finding refuge by a library. They start a fire, and Coel exits the deserted library carrying an armful of books. ‘My God, you’re not going to burn the books!’, Cilla declares in horror. ‘The Collected Works of Jacqueline Susann’, Coel reassures her, referring to the author of Valley of the Dolls and suggesting that the burning of the book wouldn’t be a great loss to culture; ‘Don’t worry: there’s a whole shelf of Harold Robbins novels’, he continues. The ‘dolls’ referenced within the title Susann’s novel of course had a double meaning, referring both to the female characters within the narrative who are exploited and treated as toys by the men in their lives; and to the ‘downer’ Dolophine (methadone), the use of the abbreviation ‘dolls’ suggesting parallels between the self-destructive (ab)use of drugs and a child’s reliance on a toy for comfort.  The story goes that Susann had prepped an idea for a sequel to the film adaptation of her most famous novel, and for this project she came up with the title ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’. However, Fox turned down Susann’s project after a number of screenplay drafts. Nevertheless, Valley of the Dolls, which featured Sharon Tate, was rereleased in 1969 following the Tate-LaBianca murders; the rerelease was a commercial success, and Fox capitalised on the still-recognisable title by financing Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls from a script by Roger Ebert. The production of the film resulted in Susann suing Fox, suggesting that the production of Meyer’s picture had ‘intentionally confused the public into thinking the film was based on her work’ and ‘infringed on her rights to the title’, also harming her credibility as a ‘serious’ author (Seaman, 1987: 405; see also Kasindorf, 1973). However, Meyer’s film goes to some lengths to distance itself from Susann’s creation, to the extent of including a title card at the start of the picture which declares that ‘The film you are about to see is not a sequel to “Valley of the Dolls”’ before establishing both pictures as taking place within a similar milieu: ’It [BVD] does, like “Valley of the Dolls”, deal with the oft-times nightmare world of show business but in a different time and context’, the title card asserts. The story goes that Susann had prepped an idea for a sequel to the film adaptation of her most famous novel, and for this project she came up with the title ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’. However, Fox turned down Susann’s project after a number of screenplay drafts. Nevertheless, Valley of the Dolls, which featured Sharon Tate, was rereleased in 1969 following the Tate-LaBianca murders; the rerelease was a commercial success, and Fox capitalised on the still-recognisable title by financing Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls from a script by Roger Ebert. The production of the film resulted in Susann suing Fox, suggesting that the production of Meyer’s picture had ‘intentionally confused the public into thinking the film was based on her work’ and ‘infringed on her rights to the title’, also harming her credibility as a ‘serious’ author (Seaman, 1987: 405; see also Kasindorf, 1973). However, Meyer’s film goes to some lengths to distance itself from Susann’s creation, to the extent of including a title card at the start of the picture which declares that ‘The film you are about to see is not a sequel to “Valley of the Dolls”’ before establishing both pictures as taking place within a similar milieu: ’It [BVD] does, like “Valley of the Dolls”, deal with the oft-times nightmare world of show business but in a different time and context’, the title card asserts.

Ten years after Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was released, Roger Ebert suggested that with the passing of each year, the picture ‘seems more and more like a movie that got made by accident when the lunatics took over the asylum’: the film’s production was ‘miraculous’, considering that it brought together an ‘independent X-rated filmmaker [Meyer] and an inexperienced screenwriter [Ebert]’ and gave them ‘carte blanche to turn out a satire of one of the studio’s [Fox’s] own hits’ (Ebert, 1980). The film itself was produced with ‘a minimum of supervision (or even cognizance) from the Front Office’ of Fox (ibid.). Beyond the Valley of the Dolls marked the beginning of the final phase of Meyer’s career as a filmmaker. David K Frasier has highlighted the four phases of Meyer’s body of work: the ‘nudie-cuties’ with which Meyer began making films (from 1959’s The Immoral Mr Teas to Heavenly Bodies in 1963); the ‘Drive-in Steinbeck’ films, a ‘period of black-and-white, synch-sound Gothic sadomasochistic melodramas’ that began with Lorna in 1964 and ended with 1965’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!; the ‘colour, synch-sound sexual dramas’ that encompassed Common Law Cabin in 1967 and Cherry, Harry and Raquel in 1969. The final films of Meyer’s career, which began with Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and ended with Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens in 1979 and were defined by Meyer’s working relationship with writer Roger Ebert, could be defined as ‘parody-satires’ (Frasier, 1990: 4).  Reflecting on the picture’s credentials as satire, Peter Michelson has highlighted the ‘grapeshot’ approach of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, arguing that by the end of the picture Meyer ‘has travestied rock and roll, hippie counterculture, racial stereotypes, Shakespeare, transvestites, Hollywood high life, feminism, television, soap operas, horror movies […] Nazis, Arthurian legends, Superwomen, romantic love, and of course titillation and pornographic prurience’, with dialogue that ‘range[s] from High Renaissance rhetoric to low ground inanity’ (Michelson, 1993: 256). Meyer’s deadpan approach to the material confounded some of the performers in the picture: ‘Meyer directed his actors with a poker face’, Ebert reflected, ‘solemnly [and] discussing the motivations behind each scene’ (Ebert, op cit.). The actors approached Ebert, asking ‘whether their dialogue wasn’t supposed to be humorous’ and confused by Meyer, who ‘discussed it [the dialogue] so seriously with them that they hesitated to risk offending him by voicing such a suggestion’ (ibid.). The outcome, Ebert argued, is a picture which ‘has a curious tone all of its own. There have been movies in which the actors played straight knowing they were in satires, and movies which were unintentionally funny because they were so bad or camp. But the tone of "BVD" comes from actors directed at right angles to the material. "If the actors perform as if they know they have funny lines, it won't work," Meyer said, and he was right’ (ibid.). Reflecting on the picture’s credentials as satire, Peter Michelson has highlighted the ‘grapeshot’ approach of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, arguing that by the end of the picture Meyer ‘has travestied rock and roll, hippie counterculture, racial stereotypes, Shakespeare, transvestites, Hollywood high life, feminism, television, soap operas, horror movies […] Nazis, Arthurian legends, Superwomen, romantic love, and of course titillation and pornographic prurience’, with dialogue that ‘range[s] from High Renaissance rhetoric to low ground inanity’ (Michelson, 1993: 256). Meyer’s deadpan approach to the material confounded some of the performers in the picture: ‘Meyer directed his actors with a poker face’, Ebert reflected, ‘solemnly [and] discussing the motivations behind each scene’ (Ebert, op cit.). The actors approached Ebert, asking ‘whether their dialogue wasn’t supposed to be humorous’ and confused by Meyer, who ‘discussed it [the dialogue] so seriously with them that they hesitated to risk offending him by voicing such a suggestion’ (ibid.). The outcome, Ebert argued, is a picture which ‘has a curious tone all of its own. There have been movies in which the actors played straight knowing they were in satires, and movies which were unintentionally funny because they were so bad or camp. But the tone of "BVD" comes from actors directed at right angles to the material. "If the actors perform as if they know they have funny lines, it won't work," Meyer said, and he was right’ (ibid.).

As Nick Yanni, writing about the film, has observed, much of the picture is remarkably restrained, especially in its depiction of sexuality (Yanni, 2004: 71). Meyer shoots the moments of coitus largely in long-shot, except for when he cuts in to closeups to emphasise a moment of comedy (such as Ashley St Claire’s hilarious screaming mid-fuck declaration that ‘There’s nothing like a Rolls! […] Nothing! […] Not even a Bentley!’). The gaze of Meyer’s camera doesn’t discriminate on the basis of sexuality, depicting the trysts between Roxanne and Casey, and between Z-Man and Lance equally objectively. However, for Yanni what makes the picture ‘torrid is the final mass-murder sequence, the most brutally violent of its kind ever: a head is lopped off and then carried around; a gun is forced into a girl’s mouth and fired, as blood spurts out and her head explodes; a German Nazi-type servant is repeatedly stabbed to death with a sword and drowned in the surf’: the film’s ‘berserk climax leaves very little to the imagination, to the accompaniment of’ Twentieth Century Fox’s immediately recognisable fanfare (ibid.). The violence, although the viewer is forewarned about it within the film’s opening titles sequence (the titles play out over a précis of the action that takes place at the climax), offers an abrupt left-turn for the narrative, which has to that point offered a satirical look at the conventions of melodrama within a ‘showbiz’ milieu. Given the setting of the narrative within the world of showbusiness, and its abrupt resolution in a moment of extreme violence, the film’s climax seems to offer an oblique reflection of the Tate-LaBianca murders, which had been covered heavily in the news media shortly before the film entered production.  Meyer’s film received an ‘X’ rating in the US, which as Ebert reminds us in his commentary was during a time before the ‘X’ had become associated with pornography and was still connected to ‘adult’ films such as John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969). Meyer reputedly disapproved of the turn towards hardcore pornography which was taking place around the time of the production of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and would snowball in the years that followed. Attending a screening of Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) with Ebert, Meyer left the film shaking his head and telling Ebert ‘I’ll never do hardcore [….] First, I don’t want to share my grosses with the Mob. Second, I’ve never been that interested in what goes on below the waist’ (Meyer, quoted in Ebert, 2005: 43). When Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was given an ‘X’ certificate, Meyer wanted to reshoot some scenes to incorporate more nudity, as he felt that ‘the ratings board felt obligated to give the “King of the Nudies” an X rating’ and had awarded the film an ‘X’ owing to Meyer’s reputation rather than the content of the picture (ibid.: 44-5). However, Fox was suffering from financial woes at the time, and Meyer’s request to turn the film into a ‘“legitimate” X-rated picture’ was declined (Lewis, 2000: 176). Meyer’s film received an ‘X’ rating in the US, which as Ebert reminds us in his commentary was during a time before the ‘X’ had become associated with pornography and was still connected to ‘adult’ films such as John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969). Meyer reputedly disapproved of the turn towards hardcore pornography which was taking place around the time of the production of Beyond the Valley of the Dolls and would snowball in the years that followed. Attending a screening of Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) with Ebert, Meyer left the film shaking his head and telling Ebert ‘I’ll never do hardcore [….] First, I don’t want to share my grosses with the Mob. Second, I’ve never been that interested in what goes on below the waist’ (Meyer, quoted in Ebert, 2005: 43). When Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was given an ‘X’ certificate, Meyer wanted to reshoot some scenes to incorporate more nudity, as he felt that ‘the ratings board felt obligated to give the “King of the Nudies” an X rating’ and had awarded the film an ‘X’ owing to Meyer’s reputation rather than the content of the picture (ibid.: 44-5). However, Fox was suffering from financial woes at the time, and Meyer’s request to turn the film into a ‘“legitimate” X-rated picture’ was declined (Lewis, 2000: 176).

In Britain, the film was cut by the BBFC when submitted for cinema classification, and again when classified for VHS release in 1989. The BBFC stipulated that the image of Z-Man running the gun along the breasts of Roxanne before inserting it in her mouth in a parody of fellatio – and pulling the trigger, leading to Rozanne’s grisly death – be excised from both the climax and the opening titles sequence. After several uncut screenings on UK television, the cuts to the film were waived when it was resubmitted in 2003. This release from Arrow is of the uncut version of the film, with a running time of 109:05 mins.

Video

The film’s DVD release from Fox was no slouch, but Arrow’s Blu-ray improves on it nevertheless. Taking up approximately 27Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Colour reproduction is very good, with the bold primary colours at the climax being particularly rich and vibrant. Clarity and detail are an improvement over the film’s already impressive previous DVD releases. Contrast levels are good and nicely balanced, giving the image a strong sense of definition and balance between light and dark – though the day for night sequence on the beach, when Ashley and Harris have their big tiff, looks as funky as a day for night sequence of that particular vintage may be expected to look (ie, with very flattened contrast and muted mid-tones). However, that’s a product of the original photography. The film’s photography tends to make heavy use of shorter focal lengths, with shorter hyperfocal distances – and thus there’s strong depth of field in many of the sequences within the picture. This presentation communicates that depth very nicely. The film’s DVD release from Fox was no slouch, but Arrow’s Blu-ray improves on it nevertheless. Taking up approximately 27Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Colour reproduction is very good, with the bold primary colours at the climax being particularly rich and vibrant. Clarity and detail are an improvement over the film’s already impressive previous DVD releases. Contrast levels are good and nicely balanced, giving the image a strong sense of definition and balance between light and dark – though the day for night sequence on the beach, when Ashley and Harris have their big tiff, looks as funky as a day for night sequence of that particular vintage may be expected to look (ie, with very flattened contrast and muted mid-tones). However, that’s a product of the original photography. The film’s photography tends to make heavy use of shorter focal lengths, with shorter hyperfocal distances – and thus there’s strong depth of field in many of the sequences within the picture. This presentation communicates that depth very nicely.

NB. Some large screengrabs can be found at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This has good range and is as rich as can be expected, with the film’s songs booming out nicely. It’s accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; these are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

DISC ONE (Blu-ray): DISC ONE (Blu-ray):

On the Blu-ray with the film are included: - an audio commentary with screenwriter Roger Ebert. In this fascinating commentary, Ebert discusses how Beyond the Valley of the Dolls came to be made, his feelings about Meyer’s films (Ebert argues that Meyer as important an independent filmmaker as John Cassavetes, for example) and the writing and production of the picture. - a second audio commentary with members of the cast, including Dolly Read, Cynthia Myers, Harrison Page, John LaZar and Erica Gavin. This is a more ‘light’ look at the picture, with the various cast members reflecting on their roles in the picture, talking about how it was received and its impact on their careers, and offering an atmosphere of good humour. Both commentaries were included on the film’s DVD release from Fox. - an introduction from John LaZar (1:27). This brief introduction features LaZar channeling the character of Z-Man. - several featurettes, again all shot in 2006 and included on the film’s previous DVD release from Fox:  -- ‘Above, Beneath and Beyond the Valley’ (30:03). This featurette features plenty of detail about the film’s production and features input from Ebert, LaZar, Meyer’s production assistant Stan Berkowitz, editor Dahn Cann and assistant Manny Diez, Meyer’s biographer Jimmy McDonough, and critics David Ansen and Nathan Rabin. The interviewees reflect on Meyer’s early career as a cameraman during the Second World War, his employment as a maker of industrial films and his work as a photographer. They discuss Meyer’s early pictures and his approach to filmmaking, reflecting on how Meyer landed the job of directing Beyond the Valley of the Dolls for Fox and his relationship with the studio. The production of BVD is discussed in detail, and the response to the film after it had been made. -- ‘Above, Beneath and Beyond the Valley’ (30:03). This featurette features plenty of detail about the film’s production and features input from Ebert, LaZar, Meyer’s production assistant Stan Berkowitz, editor Dahn Cann and assistant Manny Diez, Meyer’s biographer Jimmy McDonough, and critics David Ansen and Nathan Rabin. The interviewees reflect on Meyer’s early career as a cameraman during the Second World War, his employment as a maker of industrial films and his work as a photographer. They discuss Meyer’s early pictures and his approach to filmmaking, reflecting on how Meyer landed the job of directing Beyond the Valley of the Dolls for Fox and his relationship with the studio. The production of BVD is discussed in detail, and the response to the film after it had been made.

-- ‘Look On Up at the Bottom’ (10:59). This featurette includes Dolly Read, Cynthia Myers and Marcia McBroom, alongside input from Ebert, composer Stu Phillips and musicians Jeff McDonald (of the band Redd Kross), Paul Marshall (of the band Strawberry Alarm Clock) and Christopher Freeman (from Pansy Division). The featurette focuses on the film’s music, including Phillips’ approach to writing it and the band’s approach to performing it. -- ‘The Best of Beyond’ (12:23). In this featurette, the cast comment on the film’s lasting impact and discuss some of its more famous scenes and lines of dialogue. -- ‘Sex, Drugs, Music and Murder’ (7:25). Attempting to put the picture into its social context, this featurette discusses the counter-culture of the late-1960s and, in particular, its climax in the Manson murders at the end of the decade; events with which a number of people involved in the making of BVD had a personal connection, in one way or another. -- ‘Casey and Roxanne: The Love Scene’ (4:21). Erica Gavin and Cynthia Myers reflect on the shooting of the sex scene between their two characters. - screen tests (7:36) - stills galleries: a portraits gallery (0:33), stills (0:57), behind the scenes (0:21) and marketing materials (0:10). - trailers (4:46) DISC TWO (DVD): Included on a DVD, and more than a simple ‘extra’, is Meyer’s other picture for Fox, The Seven Minutes (1970). The film runs for 115:25 mins (PAL).  Based on Irving Wallace’s novel of the same title, this adaptation was produced as part of a three picture deal that Meyer signed with Fox. The first film was, of course, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls; in the end, Meyer only made two films for the studio (Ebert, 1980). Based on Irving Wallace’s novel of the same title, this adaptation was produced as part of a three picture deal that Meyer signed with Fox. The first film was, of course, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls; in the end, Meyer only made two films for the studio (Ebert, 1980).

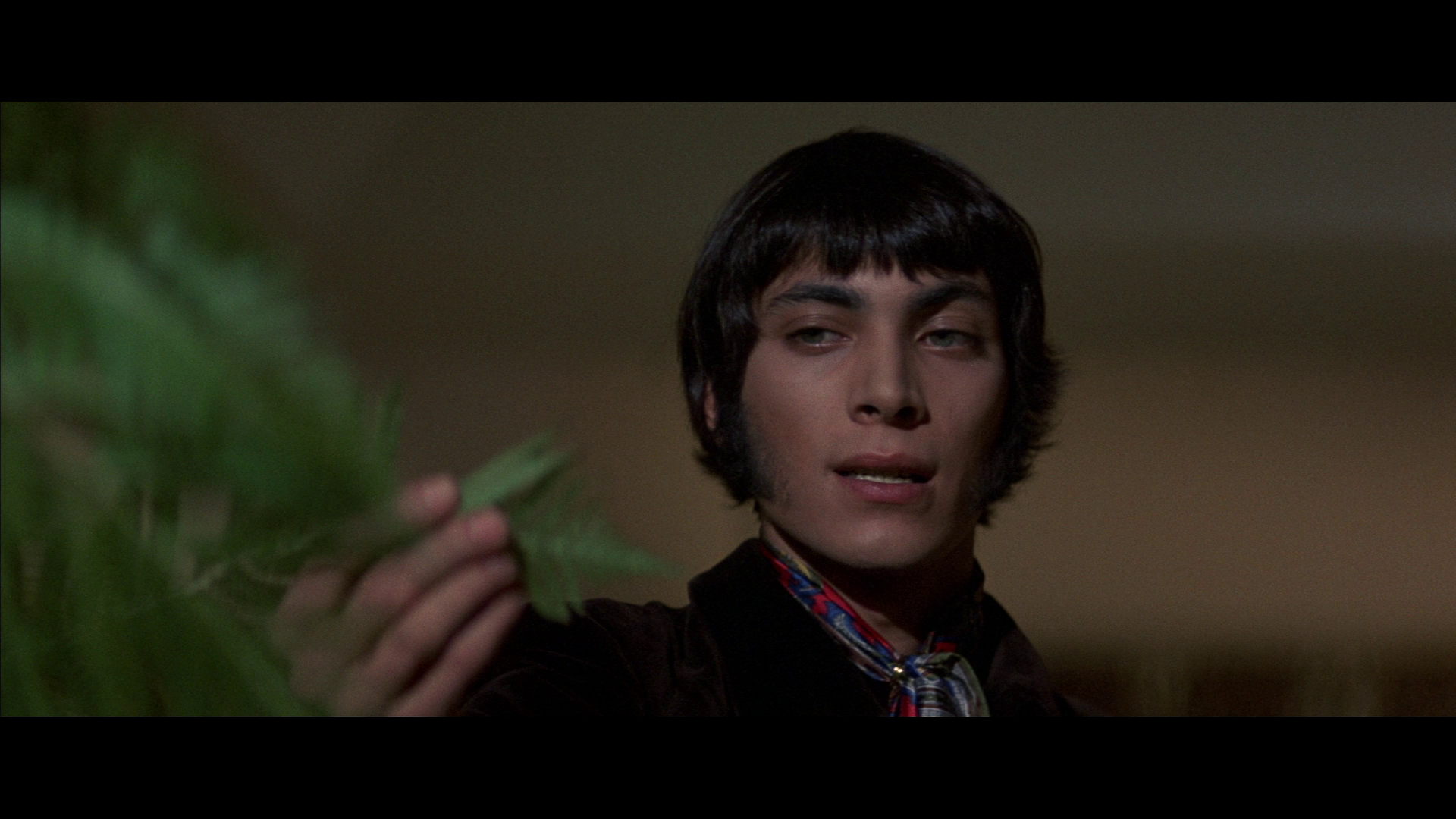

The Seven Minutes begins with two detectives, Iverson (Charles Napier) and Kellog (Charles Drake), arresting the manager of a bookshop, Ben Fremont (Robert Moloney), for selling a novel, The Seven Minutes. Within the world of the film, The Seven Minutes is a thirty year old book by a mysterious author, J J Jadway, which focuses on a woman’s recollections of her previous lovers whilst fucking her current lover. (The title, as a title card at the end of the film informs us, originates in studies which suggest that seven minutes is the average length of time it takes for a woman to achieve orgasm.) The book was at one time banned, and though it hasn’t been found obscene, it’s believed by the District Attorney that if brought to trial, it would be. The investigation is taking place after a complaint made by moral entrepreneur Olivia St Clair (Kay Peters), the President of the Strength Through Decency League. Fremont’s case reaches Phil Sanford (Tom Selleck), the owner of the company responsible for publishing The Seven Minutes. Sanford contacts his friend, lawyer Mike Barrett (Wayne Maunder), with the aim of helping Fremont. Mike approaches the DA, Elmo Duncan (Philip Carey), and asks him to drop the case against Fremont. They agree to allow Fremont to plead guilty but receive a reduced penalty: a small fine and a suspended jail sentence. However, matters become complicated when Jerry Griffith (John Sarno) is accused of the rape and murder of a young girl, Sheri Moore (Yvonne D’Angers). Jerry, it’s said, was inspired to commit the crime after reading The Seven Minutes. The reality is that Jerry didn’t rape Sheri: the attack was carried out by Jerry’s friend George (Billy Durkin), and the trauma and a fear of revealing his impotence has led Jerry to accept the blame for the event.  Jerry’s father Frank Griffith is one of the biggest contributors to Duncan’s campaign to run for senator. Seeing the case as a means to further his political ambitions, and driven behind the scenes by the influential Luther Yerkes (Jay C Flippen) and a cadre of likeminded politicos (including Yerkes’ butler, fugitive Nazi Martin Bormann), Elmo reneges on his deal with Mike and pursues the prosecution of Fremont. Prosecuting Fremont for selling the supposedly obscene book takes precedence over capturing and prosecuting the rapist and murderer of Sheri. Mike employs the services of ace investigative attorney and friend Clay Rutherford (James Inglehart). Together, and with the aid of Jerry’s cousin Maggie (Marianne McAndrew), they manage to track down the elusive J J Jadway, who is revealed to be a respected actress, Constance Cumberland (Yvonne De Carlo). Much to the chagrin of Duncan, Cumberland reveals in court that she wrote The Seven Minutes under a pseudonym and that her intentions were that the book be a ‘highly moral’ story that aimed to ‘liberate others from fear and guilt and shame’; Cumberland is also a supported of the Strength Through Decency League, and she offers a defence of the book that shatters the arguments put forwards against it by Duncan. Jerry’s father Frank Griffith is one of the biggest contributors to Duncan’s campaign to run for senator. Seeing the case as a means to further his political ambitions, and driven behind the scenes by the influential Luther Yerkes (Jay C Flippen) and a cadre of likeminded politicos (including Yerkes’ butler, fugitive Nazi Martin Bormann), Elmo reneges on his deal with Mike and pursues the prosecution of Fremont. Prosecuting Fremont for selling the supposedly obscene book takes precedence over capturing and prosecuting the rapist and murderer of Sheri. Mike employs the services of ace investigative attorney and friend Clay Rutherford (James Inglehart). Together, and with the aid of Jerry’s cousin Maggie (Marianne McAndrew), they manage to track down the elusive J J Jadway, who is revealed to be a respected actress, Constance Cumberland (Yvonne De Carlo). Much to the chagrin of Duncan, Cumberland reveals in court that she wrote The Seven Minutes under a pseudonym and that her intentions were that the book be a ‘highly moral’ story that aimed to ‘liberate others from fear and guilt and shame’; Cumberland is also a supported of the Strength Through Decency League, and she offers a defence of the book that shatters the arguments put forwards against it by Duncan.

As the film begins, even the detectives express resignations about their task of framing Fremont, the owner and manager of the Argus Book Store. ‘Cat burglar working the neighbourhood and we’re out busting a goddamn bookstore’, Iverson complains as they sit in their car outside the shop. Kellog’s ‘sting’ is really an act of entrapment: entering the shop, he asks Fremont for something ‘a little unusual’. With none of the salaciousness of other ‘smut peddlers’ in cinema – for example, the newspapershop owner who sells the under-the-counter nudie prints in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) – Fremont suggests The Seven Minutes to Kellog, telling him that it ‘was banned thirty-five years ago [….] It was considered obscene’. ‘Do you think it’s obscene?’, Kellog asks, clearly baiting Fremont. ‘Why don’t you buy the book and find out for yourself?’, Fremont asks; Meyer’s picture, through its resolution, seems to reach the same conclusion, that obscenity is in the eye of the beholder. The film constantly questions notions that obscenity can be measured objectively, quantified and ‘proven’, and underscores in a very forthright manner the ways in which such notions may be exploited for political gain.  Mike defends the novel according to the directness of its language. Faced by a witness who chastises the novel clearly without having read it, declaring that ‘I don’t have to drink poison to know that it’s poison’, Mike stages a heartfelt defence of the novel’s use of the verb ‘fucking’ to describe a specific act. ‘Would you have been happier if the writer had used such euphemisms as “they slept together” or “they were intimate” or “they made love”?’, he asks the witness, ‘If Kathleen and her lover had slept together, been intimate or made love they could have been doing many other things that the only exact word for this particular act [….] Mrs White, I’m not advocating that coarse or vulgar words should be used by everyone everywhere; I am saying that writers from Chaucer to Jadway should be allowed and permitted the freedom to use specific, precise words when writing realistically’. Sometimes Mike’s dialogue is a little too didactic: for example, during one of his first encounters with Maggie, he tells her ‘from what I know about juvenile delinquency, I’m not convinced that reading matter alone can be responsible for anti-social acts’. Mike defends the novel according to the directness of its language. Faced by a witness who chastises the novel clearly without having read it, declaring that ‘I don’t have to drink poison to know that it’s poison’, Mike stages a heartfelt defence of the novel’s use of the verb ‘fucking’ to describe a specific act. ‘Would you have been happier if the writer had used such euphemisms as “they slept together” or “they were intimate” or “they made love”?’, he asks the witness, ‘If Kathleen and her lover had slept together, been intimate or made love they could have been doing many other things that the only exact word for this particular act [….] Mrs White, I’m not advocating that coarse or vulgar words should be used by everyone everywhere; I am saying that writers from Chaucer to Jadway should be allowed and permitted the freedom to use specific, precise words when writing realistically’. Sometimes Mike’s dialogue is a little too didactic: for example, during one of his first encounters with Maggie, he tells her ‘from what I know about juvenile delinquency, I’m not convinced that reading matter alone can be responsible for anti-social acts’.

Particularly during the courtroom scenes, it’s difficult not to see Mike’s impassioned defense of the book as the intrusion of an authorial voice, a reflection of Meyer’s own attitudes towards such issues. Duncan’s stance is undermined by his association with Yerkes (and, of course, Yerkes’ butler, the fugitive Nazi Martin Bormann), though owing to Duncan’s initial attempt to reach an agreement with Mike, before the discovery of Jerry Griffith’s supposed crime inspired by the novel, it seems that Duncan is not committed to the prosecution of the book but has simply been persuaded that to pursue it would be good for his political career: he is told that through launching a crusade against ‘the smut merchants’ he will ‘become known as a protector of the young and the enemy of violence-inciting literature’. Luther tells Duncan the premise of their scheme, that the book will be used as the scapegoat for Jerry’s presumed crime against Sheri: ‘It’s very simple. Frank Griffith’s son, a poor kid with a normal sex urge, and they’re trying to pin him with “breaking and entering” [….] But you know who’s responsible? The real criminal? It’s that dirty, slimy book The Seven Minutes that incited a good kid from a decent family to commit felonious rape’. Luther’s smirk as he delivers the phrase ‘breaking and entering’, in reference to Sheri’s rape, also serves to condemn him in the eyes of the audience: willing to joke about rape both in this scene and others, Luther’s criticism of the novel comes across as wholly mealy-mouthed. Elsewhere, Luther shows a similarly sneering attitude to sexuality, referring to one of the witnesses in the case as ‘a thinking man’s faggot’ who is ‘so afraid of anything straight’ that he is ‘bound to be on our side’. (Upon discovering that Sheri has died from the injuries sustained from the attack, Luther declares cruelly that ‘the slut’s death is just the icing on the cake’.) As Duncan becomes more enmeshed in the case, his rhetoric escalates, and the conclusions he draws are (for the audience, who know that premise upon which Duncan’s case stands is faulty, that Jerry is innocent of the rape and murder of Sheri) patently fruit of the proverbial poisonous tree, to use a metaphor associated with the American legal system. Following pressure from Luther to prosecute Fremont, Duncan tells Mike that ‘Jerry Griffith is living proof that a dirty book can destroy a young boy. I’m convinced that we’re not dealing with a felony but a crime that could endanger public safety’.  However, even Mike admits that there is a qualitative difference between ‘literature’ such as The Seven Minutes and pornography. ‘A number of very important critics say The Seven Minutes is not hardcore pornography’, Mike says at one point, ‘the sort of thing that’s dumped into a drug store by quick buck printers appealing to a one-armed reader’. His comments echo the advice given to the infamous Obscene Publication Squad, the Met’s ‘dirty book squad’, in the UK by then-Home Secretary Roy Jenkins following a series of embarrassing raids on reputable galleries, that pornography could be determined by the quality of the materials on which it is printed: Jenkins reputedly said that ‘It should be pretty clear from the way a book is produced, regardless of whether it is hard or soft cover, whether or not it is hardcore pornography’ (Jenkins, quoted in Travis, 2000: np). The Home Office advised the ‘dirty book squad’ that ‘The material and quality of printing used in the production of “dirt for dirt's sake” is usually as dirty as its contents. Where, however, the material has, in the eyes of at any rate some experts, literary merit, the publication will usually be of a reasonably high quality which shows that the publisher has made a deliberate decision that his business is not likely to be placed in jeopardy by publication’ (quoted in ibid.). However, this less precise definition of what constituted obscenity in art has been argued to have led to the Obscene Publications Squad becoming increasingly corrupt in the pressuring of publishers and sellers to provide bribes (ibid.). Mike’s final declaration again seems like the voice of the author intruding into the text: to Duncan, Mike asserts, ‘you believe that all ideas and all literature should be aimed at a twelve year old. You’re a pitiful hypocrite and a political opportunist to boot. You should your clever rhetoric about God, mother and country; yet you connive and scheme without regard to anyone but yourself. It annoys me that an intelligent man cannot direct his resources and his energy for the good of the community he’s supposed to protect. Instead he spends his time racing off to court seeking a ban on those things he arbitrarily feels is bad for us’. However, even Mike admits that there is a qualitative difference between ‘literature’ such as The Seven Minutes and pornography. ‘A number of very important critics say The Seven Minutes is not hardcore pornography’, Mike says at one point, ‘the sort of thing that’s dumped into a drug store by quick buck printers appealing to a one-armed reader’. His comments echo the advice given to the infamous Obscene Publication Squad, the Met’s ‘dirty book squad’, in the UK by then-Home Secretary Roy Jenkins following a series of embarrassing raids on reputable galleries, that pornography could be determined by the quality of the materials on which it is printed: Jenkins reputedly said that ‘It should be pretty clear from the way a book is produced, regardless of whether it is hard or soft cover, whether or not it is hardcore pornography’ (Jenkins, quoted in Travis, 2000: np). The Home Office advised the ‘dirty book squad’ that ‘The material and quality of printing used in the production of “dirt for dirt's sake” is usually as dirty as its contents. Where, however, the material has, in the eyes of at any rate some experts, literary merit, the publication will usually be of a reasonably high quality which shows that the publisher has made a deliberate decision that his business is not likely to be placed in jeopardy by publication’ (quoted in ibid.). However, this less precise definition of what constituted obscenity in art has been argued to have led to the Obscene Publications Squad becoming increasingly corrupt in the pressuring of publishers and sellers to provide bribes (ibid.). Mike’s final declaration again seems like the voice of the author intruding into the text: to Duncan, Mike asserts, ‘you believe that all ideas and all literature should be aimed at a twelve year old. You’re a pitiful hypocrite and a political opportunist to boot. You should your clever rhetoric about God, mother and country; yet you connive and scheme without regard to anyone but yourself. It annoys me that an intelligent man cannot direct his resources and his energy for the good of the community he’s supposed to protect. Instead he spends his time racing off to court seeking a ban on those things he arbitrarily feels is bad for us’.

The film, presented here, is uncut and runs for 115:25 mins (PAL). The picture is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. Colours are slightly faded, but contrast levels are good and the source material is in good condition and relatively free from damage. It’s a reasonably good SD presentation of the picture. Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track, which contains some warble here and there, particularly noticeable in sequences involving music, but is clear and audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. Some large screengrabs from the presentation of this film can also be found at the bottom of this review. The film, presented here, is uncut and runs for 115:25 mins (PAL). The picture is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. Colours are slightly faded, but contrast levels are good and the source material is in good condition and relatively free from damage. It’s a reasonably good SD presentation of the picture. Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track, which contains some warble here and there, particularly noticeable in sequences involving music, but is clear and audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. Some large screengrabs from the presentation of this film can also be found at the bottom of this review.

Also on the disc is a trailer (2:55) and an episode of David Dell Valle’s television interview show Sinister Image focusing on Russ Meyer (28:04). Produced in 1987, this features Dell Valle and Meyer in conversation about Meyer’s career.

Overall

A deadpan satire of Hollywood and showbusiness in general, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is a delight to watch; it’s perhaps noticeably more restrained than the later films on which Meyer would collaborate with Ebert, but no less on-point in its satire. The film is rich in irony and caricature. It’s a superb film, and Arrow’s HD presentation of it improves noticeably on the film’s already impressive DVD releases. The contextual material, ported over from the pictures’ 2006 DVD release, is rich and informative – especially the commentary track from Ebert. A deadpan satire of Hollywood and showbusiness in general, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is a delight to watch; it’s perhaps noticeably more restrained than the later films on which Meyer would collaborate with Ebert, but no less on-point in its satire. The film is rich in irony and caricature. It’s a superb film, and Arrow’s HD presentation of it improves noticeably on the film’s already impressive DVD releases. The contextual material, ported over from the pictures’ 2006 DVD release, is rich and informative – especially the commentary track from Ebert.

Even more impressive, in terms of this release, is the inclusion of Meyer’s other film for Fox, The Seven Minutes. This film has been somewhat more elusive on home video than some of Meyer’s other pictures, and it’s a fascinating film – although at times, when Meyer’s heart is worn too boldly on his sleeve, the dialogue can be a little didactic. Although the presentation of The Seven Minutes is in SD only, it’s certainly deeply pleasing to see it included in this set, and as a consequence this release comes with a very strong recommendation. References: Ebert, Roger, 1980: ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’. Film Comment [Online.] http://www.ebertfest.com/nine/frame_bvd.html Ebert, Roger, 2005: ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’. In: Bernard, Jami (ed), 2005: The X-List: The National Society of Film Critics’ Guide to Movies That Turn Us On. Da Capo Press: 41-4 Frasier, David K, 1990: Russ Meyer—The Life and Films. London: McFarland Kasindorf, Martin, 1973: ‘Jackie Susann picks up the marbles’. The New York Times Magazine (12 August, 1973) [Online.] https://www.nytimes.com/books/98/01/04/home/susann-profile.html Lewis, Jon, 2000: Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry. New York University Press Michelson, Peter, 1993: Speaking the Unspeakable: A Poetics of Obscenity. State University of New York Press Seaman, Barbara, 1987: Lovely Me: The Life of Jacqueline Susann. New York: Seven Stories Press Travis, Alan, 2000: ‘It’s porn if the ink comes off on your hands’. The Guardian. [Online.] http://www.theguardian.com/g2/story/0,3604,368095,00.html Yanni, Nick, 2004: ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’. In: Woods, Paul A (ed), 2004: The Very Breast of Russ Meyer. London: Plexus: 71-3

|

|||||

|