|

|

Sheba, Baby (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th February 2016). |

|

The Film

‘Sheba, Baby’ (William Girdler, 1975) ‘Sheba, Baby’ (William Girdler, 1975)

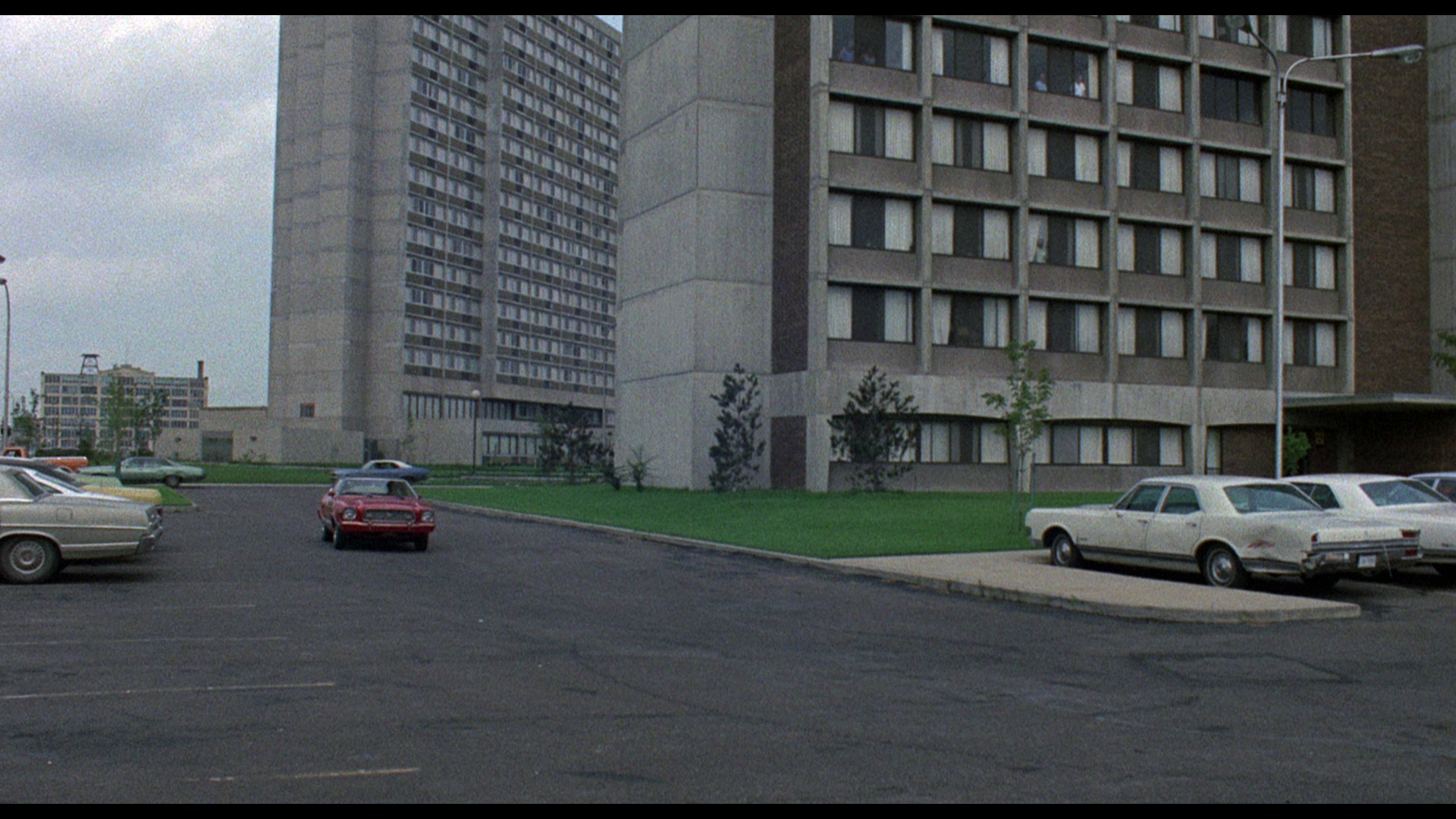

The last of a run of blaxploitation pictures made by AIP with star Pam Grier, William Girdler’s ‘Sheba, Baby’ (1975) came towards the end of Grier’s association with the studio, and more generally the blaxploitation boom itself. Usually considered relatively anaemic in comparison with AIP’s earlier Grier-starring films, such as Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973) and Foxy Brown (Jack Hill, 1974), ‘Sheba, Baby’ emulates some aspects of those earlier pictures. Famously, Grier was ‘discovered’ whilst working as a telephone switchboard operator for AIP, and went on to become one of the most iconic black actresses in American cinema. The films Grier made for AIP, alongside Tamara Dobson’s role in Jack Starrett’s Cleopatra Jones (1973), shattered the cinematic stereotypes associated with African American women – and, it could be argued, women of any ethnicity. In these films, Grier played strong, confident women who were unafraid of getting into a fight or challenging the perceived authority of male gangsters. It’s not much of a stretch to see Grier’s characters’ battle against male gangsters and mob bosses within these films as a direct assault against patriarchy; with the films’ chief villains, those working Wizard of Oz-like behind the scenes, often revealed to be white men of wealth and position, Grier’s battle is often coded as a struggle against white, masculine wealth and authority. Where African American women had traditionally been depicted as servants or deviants in Hollywood films, Grier essayed a new representation of black women as strong, independent and utterly capable. Even in blaxploitation films more generally, black women were largely represented as sex objects, with the characters ‘emerg[ing] as sex toys for the films’ [male] protagonists’ (Lawrence, 2007: np). Films such as Coffy, Foxy Brown and ‘Sheba, Baby’, in which African American women are depicted as ‘strong, three-dimensional characters’, therefore ‘work in direct opposition to the traditional portrayals of black women’ both in mainstream cinema and in the more specific context of blaxploitation films (ibid.).  ‘Sheba, Baby’ begins in Louisville, at the loan agency owned and operated by Andy Shayne (Rudy Challenger) and Brick (Austin Stoker). One night, as Andy and Brick are closing the agency for the evening, a group of hired thugs enter the front office and trash it. When Andy tackles them, the thugs attack him and leave him badly beaten. ‘Sheba, Baby’ begins in Louisville, at the loan agency owned and operated by Andy Shayne (Rudy Challenger) and Brick (Austin Stoker). One night, as Andy and Brick are closing the agency for the evening, a group of hired thugs enter the front office and trash it. When Andy tackles them, the thugs attack him and leave him badly beaten.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, private investigator Sheba Shayne returns to the PI business she runs with her slacker partner Racker (Edward Reece). Sheba is Andy’s daughter, and she receives from Racker news of the assault upon Andy. Concerned for her father, Sheba departs for Louisville immediately. She is warned by both Andy and Brick to stay away from the thugs who attacked her father; but prior to becoming a private detective, Sheba worked for the Louisville police department and, after a car bomb is planted on her father’s car, she seeks the help of a former colleague, a detective within the police department. However, she is turned away, her attempts to counteract the work of the gangsters via legitimate means apparently thwarted. Frustrated by the police’s lack of interest in the case, Sheba decides to proceed with her own investigation. She is aided by Brick, a long-time acquaintance with whom she develops a sexual relationship. Sheba’s queries lead her to a man named Jenkins, who is meeting with some other gangsters at midnight. Sheba decides to interrupt Jenkins’ midnight meeting and enlists the help of Brick to do so. Brick reluctantly agrees. Their interruption of the meeting leads to a shootout. Sheba and Brick’s investigation of the gang stirs up a proverbial hornet’s nest, and one morning a group of armed white men burst through the door of the Shayne loan agency. The men hold everyone in the building – including Sheba, Andy and Brick – hostage. Sheba fights back, managing to shoot and kill or injure the majority of the thugs; however, in the crossfire Andy is wounded fatally. He is taken to hospital but dies shortly afterwards. Following Andy’s death, Sheba continues her investigation. Her inquiries lead her to a pimp named Walker (Christopher Joy). Walker gives Sheba the name of Pilot (D’Urville Martin), the street-level boss of the gang that attacked Andy. Pilot points Sheba towards Shark (Dick Merrifield), a wealthy white man who has been directing the activities of Pilot’s gang from behind the scenes.  In the opening scenes of ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba is quickly established as a confident woman who is unafraid of challenging men when she returns to the offices of Racker & Shayne Private Investigators and chastises her partner Racker for his sloppy approach to housekeeping. ‘Look at this place’, she complains, ‘I go away for three days, and I come back and the whole place has gone to pot’. Despite Sheba’s past as a police officer and her current status as a private investigator, Andy tries to encourage her to keep a distance from the events that have been taking place in Louisville: ‘I want you to stay out of this, Little Andy’, he tells Sheba, addressing her by his pet name for her, ‘I don’t want my daughter messing around with these kinds of people’. Sheba resists, telling her father, ‘Daddy, I know you think I’m doing a man’s job, but I’m not going to sit on the sidelines just because I’m a woman’. When Sheba approaches her former colleague, a detective, for help in apprehending the men who attacked her father, she finds herself similarly warned away: ‘Stay out of it, Sheba’, she is told by the detective. ‘Stay out of it? That’s your job’, she bites back, referring to the police’s lack of interest in the case. In the opening scenes of ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba is quickly established as a confident woman who is unafraid of challenging men when she returns to the offices of Racker & Shayne Private Investigators and chastises her partner Racker for his sloppy approach to housekeeping. ‘Look at this place’, she complains, ‘I go away for three days, and I come back and the whole place has gone to pot’. Despite Sheba’s past as a police officer and her current status as a private investigator, Andy tries to encourage her to keep a distance from the events that have been taking place in Louisville: ‘I want you to stay out of this, Little Andy’, he tells Sheba, addressing her by his pet name for her, ‘I don’t want my daughter messing around with these kinds of people’. Sheba resists, telling her father, ‘Daddy, I know you think I’m doing a man’s job, but I’m not going to sit on the sidelines just because I’m a woman’. When Sheba approaches her former colleague, a detective, for help in apprehending the men who attacked her father, she finds herself similarly warned away: ‘Stay out of it, Sheba’, she is told by the detective. ‘Stay out of it? That’s your job’, she bites back, referring to the police’s lack of interest in the case.

The film offers a series of dialectical positions. These begin with Andy and Brick’s differences of opinion as to how to handle Pilot’s threats, and continue with Brick and Sheba’s disagreements as to how best to deal with Pilot and his gang. In each of these dialogues, Brick offers a more moderate position in relation to the hotheaded arguments put forward by both Andy and his daughter Sheba. Brick advises Andy that he ‘can’t keep ignoring him [Pilot, presumably]. At least talk to him’. However, Andy resists, telling Andy, ‘I’m not going to bow down to them, Brick. I’ve got a responsibility to the people of this community’. The film thus quickly establishes Andy as a loan agent with good intentions, a man who is offering loans to the people of the local community so as to ensure they don’t turn to more unscrupulous loan sharks. ‘I’m not saying to give in, Andy’, Brick protests weakly, ‘But we’ve got to deal with them’. ‘I’ve been bullied by people like this all my life, and so have you’, Andy reminds the younger man: ‘There’s only one way to fight them back’, he says, ‘and that’s by giving our people fair deals. And as long as we give them fair deals, they’ll support us’. Brick warns Andy that ‘These people are ruthless men. They’ll kill you’. Brick’s warning is, of course, proven to be true: Andy’s death does indeed come at the hands of Pilot and Shark’s hired thugs. However, this doesn’t undermine the moral sense within Andy’s argument: that one simply can’t bow down to bullies and gangsters.  When Sheba tries to enlist Brick’s help in gatecrashing Jenkins’ midnight rendezvous, she faces resistance from Brick initially. He reminds Sheba that her private investigator’s license doesn’t place her above the law, that it is ‘not a warrant to arrest anybody with, and second of all we’re not equipped to fight a bunch like that, not on their terms’. Sheba protests vociferously, telling brick ‘that’s the only way to fight ‘em is on their own terms’. ‘Not outside the law’, Brick warns Sheba. ‘We’ll just have to bend the law’, she tells him, ‘This is dad’s life we’re talking about’. Sheba ridicules Brick’s worldview as having no place in the real world, telling him ‘you still think everything can be solved by logic. Well, these people don’t even know what logic means; they can’t even spell it’. When, following the shooting of Andy, Sheba holds her gun at the head of one of the group of hired gun thugs who have shot up her father’s business, the man begs for his life. Sheba is stopped from executing the man only by Brick’s gentle warning to her: he reminds her not to step over the proverbial line by murdering the man in front of her. As Sheba’s investigations lead her closer to Pilot and, later, Shark, her methods become more brutal. When she finally catches up with Pilot at a fairground, Sheba holds his head to the track of a rollercoaster in front of an oncoming carriage, demanding that he tell her who he works for. However, as the film moves towards its conclusion even Brick is forced to admit that Sheba’s methodology seems to be the only means by which the film’s antagonists may be brought to book. Following Sheba’s interrogation of Pilot, Brick is told by Sheba’s former partner in the police force that he must ‘get her [Sheba] out of town’. The detective continues, telling Brick ‘If people would only stop medaling and let the police do their work’. However, Brick defends Sheba; he responds to the detective’s assertion by stating, ‘Look, we tried that, Lieutenant, don’t you remember. It didn’t work out’. When Sheba tries to enlist Brick’s help in gatecrashing Jenkins’ midnight rendezvous, she faces resistance from Brick initially. He reminds Sheba that her private investigator’s license doesn’t place her above the law, that it is ‘not a warrant to arrest anybody with, and second of all we’re not equipped to fight a bunch like that, not on their terms’. Sheba protests vociferously, telling brick ‘that’s the only way to fight ‘em is on their own terms’. ‘Not outside the law’, Brick warns Sheba. ‘We’ll just have to bend the law’, she tells him, ‘This is dad’s life we’re talking about’. Sheba ridicules Brick’s worldview as having no place in the real world, telling him ‘you still think everything can be solved by logic. Well, these people don’t even know what logic means; they can’t even spell it’. When, following the shooting of Andy, Sheba holds her gun at the head of one of the group of hired gun thugs who have shot up her father’s business, the man begs for his life. Sheba is stopped from executing the man only by Brick’s gentle warning to her: he reminds her not to step over the proverbial line by murdering the man in front of her. As Sheba’s investigations lead her closer to Pilot and, later, Shark, her methods become more brutal. When she finally catches up with Pilot at a fairground, Sheba holds his head to the track of a rollercoaster in front of an oncoming carriage, demanding that he tell her who he works for. However, as the film moves towards its conclusion even Brick is forced to admit that Sheba’s methodology seems to be the only means by which the film’s antagonists may be brought to book. Following Sheba’s interrogation of Pilot, Brick is told by Sheba’s former partner in the police force that he must ‘get her [Sheba] out of town’. The detective continues, telling Brick ‘If people would only stop medaling and let the police do their work’. However, Brick defends Sheba; he responds to the detective’s assertion by stating, ‘Look, we tried that, Lieutenant, don’t you remember. It didn’t work out’.

Like many blaxploitation pictures, ‘Sheba, Baby’ was a ‘black’ film made by a mostly white crew. Jack Hill has talked about the production of Coffy as lacking input from black crew members simply owing to the fact that there was a lack of black technicians within the film industry, especially those who were union members: ‘it was very difficult to get into the union and you had to have years and years of experience’ (Hill, quoted in Walker et al, 2009: 104). This valuable experience was something that black crew members struggled to gain owing to prejudices that existed within the film industry, which reflected wider issues of prejudice within American society during that era. However, Hill has stated that he hoped that ‘the success of those films—with a general audience, not solely a black audience—contributed to the acceptance by audiences of black characters and black lifestyles in films’, gradually bringing ‘black characters and black lifestyles into mainstream films’ (ibid.: 105). Blaxploitation pictures made by black filmmakers were few and far between: notable exceptions, of course, include Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song (1971), documentary photographer Gordon Parks’ Shaft (1971) and Parks’ son Gordon Parks Jr’s Super Fly (1972).  Whilst the fact that the film is a ‘black’ picture made by a ‘white’ crew doesn’t detract from the strength of Grier’s character within the narrative, it arguably makes the film’s heavy and aggressive use of the word ‘nigger’ as a negative racial epithet difficult to swallow. Although a feature of a number of blaxploitation pictures, ‘Sheba, Baby’s potentially challenging use of the word ‘nigger’ is notable. It’s a word which the script of ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to use more frequently and aggressively than the majority of blaxploitation pictures. The word is first used casually by Sheba (‘I come home and find my father beaten half to death, and here’s some sweet-talking nigger threatening his life, and you say “Forget about it”?’, she asks Brick upon arriving in Lousville) but is rapidly used in various aggressive and demeaning contexts. In a later sequence the word is used ironically, within a context that seems to reference Hollywood’s problematic relationship with the issue of ethnic difference. In this sequence, Sheba interrogates one of the men who she believes may lead her to the gang that assaulted her father. She torments the man by dipping his head in a tub of what appears to be calcium hypochlorite; the African American man’s face is made white by the powder, in what seems to be a deliberate parody of Hollywood’s frequent use of ‘blackfacing’. Over this image, Sheba warns the man: ‘You’d better tell me all you know, or you’ll be the whitest nigger that ever left Louisville’. The word becomes even more threatening later in the picture, when the group of white men, presumably hired by Pilot and Shark, break into Shayne’s office and threaten the family and their clients at gunpoint. ‘Now you just keep your mouth shut, nigger, or I’m gonna blow a hole in your head’, the spokesman of this group of gun thugs tells Andy cruelly. Later, the violence within the picture becomes more defined along ethnic lines when Shark and his group of white thugs capture Sheba and Pilot, and Shark torments and executes Pilot. Before he does so, Shark tells Pilot ‘A lot of things have to be cleaned up, and you’re one of them’, referring to Pilot as a ‘Slimy nigger’. The line is spat out with absolute venom. As noted above, the use of the word ‘nigger’ in blaxploitation films isn’t especially uncommon, but amongst the mainstream examples of the form ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to use the word in a more aggressive context and a manner which foregrounds the difference between the person saying the word and those to whom it is directed. Whilst the fact that the film is a ‘black’ picture made by a ‘white’ crew doesn’t detract from the strength of Grier’s character within the narrative, it arguably makes the film’s heavy and aggressive use of the word ‘nigger’ as a negative racial epithet difficult to swallow. Although a feature of a number of blaxploitation pictures, ‘Sheba, Baby’s potentially challenging use of the word ‘nigger’ is notable. It’s a word which the script of ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to use more frequently and aggressively than the majority of blaxploitation pictures. The word is first used casually by Sheba (‘I come home and find my father beaten half to death, and here’s some sweet-talking nigger threatening his life, and you say “Forget about it”?’, she asks Brick upon arriving in Lousville) but is rapidly used in various aggressive and demeaning contexts. In a later sequence the word is used ironically, within a context that seems to reference Hollywood’s problematic relationship with the issue of ethnic difference. In this sequence, Sheba interrogates one of the men who she believes may lead her to the gang that assaulted her father. She torments the man by dipping his head in a tub of what appears to be calcium hypochlorite; the African American man’s face is made white by the powder, in what seems to be a deliberate parody of Hollywood’s frequent use of ‘blackfacing’. Over this image, Sheba warns the man: ‘You’d better tell me all you know, or you’ll be the whitest nigger that ever left Louisville’. The word becomes even more threatening later in the picture, when the group of white men, presumably hired by Pilot and Shark, break into Shayne’s office and threaten the family and their clients at gunpoint. ‘Now you just keep your mouth shut, nigger, or I’m gonna blow a hole in your head’, the spokesman of this group of gun thugs tells Andy cruelly. Later, the violence within the picture becomes more defined along ethnic lines when Shark and his group of white thugs capture Sheba and Pilot, and Shark torments and executes Pilot. Before he does so, Shark tells Pilot ‘A lot of things have to be cleaned up, and you’re one of them’, referring to Pilot as a ‘Slimy nigger’. The line is spat out with absolute venom. As noted above, the use of the word ‘nigger’ in blaxploitation films isn’t especially uncommon, but amongst the mainstream examples of the form ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to use the word in a more aggressive context and a manner which foregrounds the difference between the person saying the word and those to whom it is directed.

The template for ‘Sheba, Baby’ was established in Coffy, a film that was produced as a response to Cleopatra Jones. Cleopatra Jones had been offered to AIP before being produced by Warner Bros, and Coffy was intended by AIP’s head of production Jack Gordon as a sop in the face to Cleopatra Jones’s producer William Tennant: Gordon had seen Tennant as betraying AIP owing to the fact that Tennant presented the Cleopatra Jones project to Gordon before backing out of the deal with AIP when Warners offered more money. With Coffy, Gordon intended to beat Cleopatra Jones to the punch (Coffy was ultimately released three weeks before Cleopatra Jones) by offering a film featuring a black female protagonist – but unlike the ‘law-abiding heroine’ of Cleopatra Jones, Pam Grier’s protagonist of Coffy was to be ‘a black female vigilante’ (Lawrence, op cit.: np). This vigilante character would become indelibly associated with Pam Grier’s roles in the blaxploitation pictures she made during the early 1970s, and she plays an essentially identical role in ‘Sheba, Baby’: Sheba Shayne is a private detective who, returning to Chicago, works outside the law to bring down the gang headed by Pilot and Shark. A number of scenes foreground the film’s emphasis on vigilante justice. This is particularly true of the scene in which Pilot and Shark’s hired thugs, white mobsters with guns and sunglasses, invade Andy Shayne’s business and hold everyone inside at gunpoint. Sheba eradicates the threat by pulling out her own gun and shooting the villains; she holds her gun at one of them, who is wounded and begging for his life, and a close-up of Sheba shows her reaction to the dilemma – whether or not she should pull the trigger, executing an unarmed man. She is only stopped by Brick, who, as the police arrive, quietly warns her not to murder the man. The template for ‘Sheba, Baby’ was established in Coffy, a film that was produced as a response to Cleopatra Jones. Cleopatra Jones had been offered to AIP before being produced by Warner Bros, and Coffy was intended by AIP’s head of production Jack Gordon as a sop in the face to Cleopatra Jones’s producer William Tennant: Gordon had seen Tennant as betraying AIP owing to the fact that Tennant presented the Cleopatra Jones project to Gordon before backing out of the deal with AIP when Warners offered more money. With Coffy, Gordon intended to beat Cleopatra Jones to the punch (Coffy was ultimately released three weeks before Cleopatra Jones) by offering a film featuring a black female protagonist – but unlike the ‘law-abiding heroine’ of Cleopatra Jones, Pam Grier’s protagonist of Coffy was to be ‘a black female vigilante’ (Lawrence, op cit.: np). This vigilante character would become indelibly associated with Pam Grier’s roles in the blaxploitation pictures she made during the early 1970s, and she plays an essentially identical role in ‘Sheba, Baby’: Sheba Shayne is a private detective who, returning to Chicago, works outside the law to bring down the gang headed by Pilot and Shark. A number of scenes foreground the film’s emphasis on vigilante justice. This is particularly true of the scene in which Pilot and Shark’s hired thugs, white mobsters with guns and sunglasses, invade Andy Shayne’s business and hold everyone inside at gunpoint. Sheba eradicates the threat by pulling out her own gun and shooting the villains; she holds her gun at one of them, who is wounded and begging for his life, and a close-up of Sheba shows her reaction to the dilemma – whether or not she should pull the trigger, executing an unarmed man. She is only stopped by Brick, who, as the police arrive, quietly warns her not to murder the man.

More directly, ‘Sheba, Baby’ emulates some of the narrative beats of Coffy. In both films, Grier’s character avenges the death of a family member; and both pictures see Grier’s character masquerading as an escort in order to get within striking distance of the main antagonist (in this film, Shark), resulting in both instances in a catfight (in ‘Sheba, Baby’, with Shark’s lover). Coffy offers a sequence in which the mob boss Vitroni (Allan Arbus) sends two heavies to murder a pimp, ‘King’ George (Robert DoQui). The thugs tie a noose around ‘King’ George’s neck and drag him from a car in a grotesque parody of a lynching (‘This is how we lynch niggers’, asserts one of the heavies, played by Sid Haig). ‘Sheba, Baby’ delivers a near-identical sequence, clearly modeled on that in the earlier picture, although in this film the car is substituted for a speedboat. Having learnt that Pilot has unwittingly led Sheba to Shark, Shark has his men accost and torment Pilot before executing him by towing him behind a speedboat.  Additionally, in Coffy the mob boss Vitroni is ultimately revealed to be nothing more than the agent of the will of the film’s ‘real’ villain, Coffy’s lover Howard Brunswick (Booker Bradshaw), who intends to run for Congress but has betrayed the people of the community he claims to represent by working in league with drug dealers and criminals: the criminal fraternity is thus shown to be operating under the directions of – or at least in alliance with – a figure within ‘legitimate’ society. Similarly, in ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba Shayne’s investigations lead her first to Pilot, the black leader of the gang which is strongarming small businesses like her father’s, and then on to the man for whom Pilot works: Shark, a wealthy white man who, whilst still a gangster, seems to move in far more ‘legitimate’ circles to Pilot. When captured by Shark and his goons, Sheba is taken aboard Shark’s yacht, where Shark holds society soirées. ‘I knew no-one legitimate could own a boat like this’, she says, referring to her first sight of the yacht when Shark was throwing a high society party aboard it. ‘Yacht, my dear’, Shark responds, correcting Sheba’s misuse of the word ‘boat’. ‘Do you have trouble sleeping at night?’, Sheba asks him. ‘From taking money from stupid, ignorant people? No’, Shark says, adding that ‘You have to admire a man for the goals that he sets’. Shark reflects on the quietness of the setting, the rural location and the body of water on which his yacht sits: ‘I like it out here. It’s quiet. Gets me away from all the shit in the city’, he says. ‘I don’t see how’, Sheba tells him, ‘You seem to bring it all with you’. Sheba continues by commenting on Shark’s work as a conman: ‘You get them coming and going, don’t you’, she observes. ‘It’s the nature of the game’, Shark tells her. ‘With a marked deck’, Sheba adds. ‘Of course’, Shark says, ‘Anything worth having is worth stealing’. Additionally, in Coffy the mob boss Vitroni is ultimately revealed to be nothing more than the agent of the will of the film’s ‘real’ villain, Coffy’s lover Howard Brunswick (Booker Bradshaw), who intends to run for Congress but has betrayed the people of the community he claims to represent by working in league with drug dealers and criminals: the criminal fraternity is thus shown to be operating under the directions of – or at least in alliance with – a figure within ‘legitimate’ society. Similarly, in ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba Shayne’s investigations lead her first to Pilot, the black leader of the gang which is strongarming small businesses like her father’s, and then on to the man for whom Pilot works: Shark, a wealthy white man who, whilst still a gangster, seems to move in far more ‘legitimate’ circles to Pilot. When captured by Shark and his goons, Sheba is taken aboard Shark’s yacht, where Shark holds society soirées. ‘I knew no-one legitimate could own a boat like this’, she says, referring to her first sight of the yacht when Shark was throwing a high society party aboard it. ‘Yacht, my dear’, Shark responds, correcting Sheba’s misuse of the word ‘boat’. ‘Do you have trouble sleeping at night?’, Sheba asks him. ‘From taking money from stupid, ignorant people? No’, Shark says, adding that ‘You have to admire a man for the goals that he sets’. Shark reflects on the quietness of the setting, the rural location and the body of water on which his yacht sits: ‘I like it out here. It’s quiet. Gets me away from all the shit in the city’, he says. ‘I don’t see how’, Sheba tells him, ‘You seem to bring it all with you’. Sheba continues by commenting on Shark’s work as a conman: ‘You get them coming and going, don’t you’, she observes. ‘It’s the nature of the game’, Shark tells her. ‘With a marked deck’, Sheba adds. ‘Of course’, Shark says, ‘Anything worth having is worth stealing’.

Mia Mask argues that for Pam Grier, Coffy ‘served as the bridge from sexploitation to Blaxploitation’, offering Grier her first starring role (Mask, 2009: 89). Prior to Coffy, Grier’s screen roles had been limited to secondary roles in films such as the ‘women in prison’ pictures The Big Doll House (Jack Hill, 1971), Women in Cages (Gerardo de Leon, 1971) and The Big Bird Cage (Jack Hill, 1972). In these films, Grier (along with the rest of the female cast) had been utterly objectified, with the focus being on her characters’ sexual exploitation. In Coffy, by contrast, Grier’s character is fully aware of her own sexuality and uses it to entrap the male antagonists. Dominique Mainon and James Ursini note that Grier’s Coffy ‘uses her sexual allure, as well as her physical strength and acute intelligence, to defeat her enemies’ (Mainon & Ursini, 2006: 222). The character ‘gains the trust of the male characters […] by using the sexual stereotypes they project on her, and then reverses the stereotype, to the consternation of the unwitting character’ (ibid.). In ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba attempts to use her sexuality against Shark but is quickly shot down. When Shark catches up with Sheba, she tries to distract him by behaving seductively, but Shark resists, telling her, ‘Now you listen, and you listen good. I hereby sentence you to death. Before we’re finished with you, you’re going to be Shark bait’.  Phillippa Gates argues that both ‘Sheba, Baby’ and Arthur Marks’ Friday Foster, Grier’s other blaxploitation film of 1975 (and the films that marked her departure from the subgenre), ‘follow the same formula as Coffy, Cleopatra Jones, and Foxy Brown, they offer toned-down versions of the earlier films’ heroines’ (Gates, 2011: 206). Gates notes that in ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba Shayne is ‘less empowered’ than Coffy or Foxy Brown and ‘lack[s] the ability (read: opportunity) to act heroically’ (ibid.). Unlike Coffy and Foxy Brown, Grier’s character in ‘Sheba, Baby’ is ‘no longer a lone vigilante’ but is instead a ‘professional investigator’ and a former police officer (ibid.). On the other hand, Yvonne D Sims has argued that because Coffy was ‘the first of Grier’s action heroines, she was not as polished or sophisticated as her later heroines’ (Sims, 2006: 77). As Grier moved through the films she made after Coffy, ‘[h]er growing self-confidence as an actress translated to more sophisticated onscreen heroines despite under-developed plots’ (ibid.). Phillippa Gates argues that both ‘Sheba, Baby’ and Arthur Marks’ Friday Foster, Grier’s other blaxploitation film of 1975 (and the films that marked her departure from the subgenre), ‘follow the same formula as Coffy, Cleopatra Jones, and Foxy Brown, they offer toned-down versions of the earlier films’ heroines’ (Gates, 2011: 206). Gates notes that in ‘Sheba, Baby’, Sheba Shayne is ‘less empowered’ than Coffy or Foxy Brown and ‘lack[s] the ability (read: opportunity) to act heroically’ (ibid.). Unlike Coffy and Foxy Brown, Grier’s character in ‘Sheba, Baby’ is ‘no longer a lone vigilante’ but is instead a ‘professional investigator’ and a former police officer (ibid.). On the other hand, Yvonne D Sims has argued that because Coffy was ‘the first of Grier’s action heroines, she was not as polished or sophisticated as her later heroines’ (Sims, 2006: 77). As Grier moved through the films she made after Coffy, ‘[h]er growing self-confidence as an actress translated to more sophisticated onscreen heroines despite under-developed plots’ (ibid.).

Some of these differences from Grier’s earlier films, Kelly Hankin suggests, are owing to the fact that ‘Sheba, Baby’ was produced towards the end of the boom of blaxploitation pictures that took place in the early 1970s (Hankin, 2002: 111). As such, ‘Sheba, Baby’ evidenced ‘the growing public dissatisfaction with blaxploitation violence and ghetto glamorization’ by taking elements of Grier’s characters from Coffy and Foxy Brown and softening them considerably (ibid.). One of the ways in which this was achieved was by making Grier’s character, Sheba Shayne, a licensed private investigator who was also a former police officer – rather than a vigilante operating completely outside the law. This decision reputedly frustrated black audiences, who according to James Robert Parish and George H Hill were ‘baffled by the tentativeness of this new entry’ (Parish & Hill, quoted in ibid.). Following ‘Sheba, Baby’, Grier established her intent to move away from the blaxploitation subgenre to take roles in more ‘serious’ pictures, severing her connection with AIP and the black action film; however, Grier struggled to establish a screen presence away from the blaxploitation pictures that had made her famous (ibid.).

Video

Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the film is uncut here, with a running time of 89:41 mins. (When submitted to the BBFC in 1975, the only time the picture has previously been submitted for classification in the UK, the picture was cut for a ‘AA’ rating; the cuts to that version were presumably to the moments of violence within the film.) Here, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 24Gb of space. It’s a nicely balanced, detailed image. There’s a very slight softness here and there which suggests that noise reduction may have been applied somewhere along the line. Like a lot (but not all!) of the blaxploitation pictures, ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to have been shot quickly and relatively cheaply, and as a consequence there’s a flatness to the original photography – though a few scenes stand out as being lensed very nicely, such as a shot of Sheba and Brick filmed with a long lens that flattens perspective against a fountain. It’s an interesting, almost abstracted image that works very well. Especially in its opening sequences, the film features a heavy use of nighttime sequences, and the well-balanced contrast levels within this presentation carry those sequences very well: there’s a good balance of light and dark, with clear midtones present throughout. The image throughout is clear and free of damage and debris. Finally, a characteristically strong encode ensures that the image has the structure of 35mm film, giving the whole presentation a satisfyingly organic appearance. Presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the film is uncut here, with a running time of 89:41 mins. (When submitted to the BBFC in 1975, the only time the picture has previously been submitted for classification in the UK, the picture was cut for a ‘AA’ rating; the cuts to that version were presumably to the moments of violence within the film.) Here, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 24Gb of space. It’s a nicely balanced, detailed image. There’s a very slight softness here and there which suggests that noise reduction may have been applied somewhere along the line. Like a lot (but not all!) of the blaxploitation pictures, ‘Sheba, Baby’ seems to have been shot quickly and relatively cheaply, and as a consequence there’s a flatness to the original photography – though a few scenes stand out as being lensed very nicely, such as a shot of Sheba and Brick filmed with a long lens that flattens perspective against a fountain. It’s an interesting, almost abstracted image that works very well. Especially in its opening sequences, the film features a heavy use of nighttime sequences, and the well-balanced contrast levels within this presentation carry those sequences very well: there’s a good balance of light and dark, with clear midtones present throughout. The image throughout is clear and free of damage and debris. Finally, a characteristically strong encode ensures that the image has the structure of 35mm film, giving the whole presentation a satisfyingly organic appearance.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, which is in English (naturally). This track is clear and rich. The music has a bassy ‘punch’ to it. A good sense of range is present within the audio track. It’s accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The disc includes two audio commentaries: one with writer David Sheldon, and the other with Patty Breen. The disc includes two audio commentaries: one with writer David Sheldon, and the other with Patty Breen.

In the first commentary by Sheldon, the film’s writer talks about his work for AIP and his association with Pam Grier. He talks about the origins of this picture in the treatment he wrote for Coffy. Sheldon discusses his aims for Sheba, Baby and the intention to make a picture that was a little more mainstream than both Coffy and Foxy Brown. It’s an engaging commentary track, filled with fascinating anecdotes. The second commentary by Patty Breen is an enthusiastic examination of the picture from the owner of williamgirdler.com. Breen discusses the origins of her website and its development over time. She asserts that she’s ‘confident I’ve watched ‘Sheba, Baby’ more times than any other human being alive today’, and she discusses the pictures development and its place within Girdler’s body of work as a whole. Alongside this, the disc contains: - ‘Sheldon Baby’ (15:16). In this new interview, the film’s writer David Sheldon discusses how he came to work for AIP and his working relationship with Larry Gordon. David Sheldon left AIP with two pictures to be produced, one of which was ‘Sheba, Baby’. Sheldon reveals that ‘Sheba, Baby’s script was originally intended for Coffy: when Coffy was originally greenlit, there wasn’t a script, so Sheldon created a treatment for the picture. However, Sheldon’s script for Coffy was thrown out by Jack Hill, who wrote his own screenplay for the picture, and Sheldon’s script evolved into ‘Sheba, Baby’. Sheldon also talks about some of the other pictures with which he was involved, including Slaughter (Jack Starrett, 1972) and Devil Times Five (Sean MacGregor, 1973). He discusses his working relationship with William Girdler, which originated with Sheldon’s appreciation of Girdler’s work on Three on a Meathook (1973). Sheldon talks about his work with Girdler on Abby (1974) too. Sheldon talks about ‘Sheba, Baby’s production. ‘Sheba, Baby’ was made for more money than AIP’s previous Pam Grier pictures, and in order to persuade Grier to take the role AIP promised her that the film wouldn’t contain the nudity that Coffy and Foxy Brown had: ‘she could be a little more elegant in the picture’, Sheldon says. The picture was originally titled ‘Honor’ but the title, and the name of the main character, was changed at the behest of Samuel Z Arkoff, who suggested that the marketing department would find ‘Sheba, Baby’ easier to sell. - ‘Pam Grier: The AIP Years’ (11:54). In another new interview, critic Chris Poggiali talks about Pam Grier’s ascendancy within AIP. Poggiali discusses the motives behind making Coffy and Jack Hill’s contribution to the picture. He compares Coffy with Cleopatra Jones before talking about Foxy Brown and Scream, Blacula, Scream (Bob Kellijan, 1973), which features Grier in a fairly small role. ‘Sheba, Baby’ features Grier playing a slightly different type of character as a means of ‘get[ting] away from the characters she had played in the two previous films’. Poggiali suggests that although ‘Sheba, Baby’ establishes Grier’s character as a private investigator, ultimately her role in the film is in ‘the type of investigation that Coffy did as a nurse’. He moves on to discussing Friday Foster, which was Grier’s last picture for AIP and, though a ‘more mainstream film’ than Grier’s previous films for the studio, the last blaxploitation film that Grier made – though as Poggiali argues, it’s not really a blaxploitation picture at all. This film was intended to be a ‘transition film’ for Grier, offering her passage away from AIP and into more ‘serious’ fare – though ‘the sad thing is, she never became a leading lady in major studio films’. - Trailer (1:54). - Gallery (0:18). Retail copies include reversible artwork and a booklet that contains a new article by Patty Breen, illustrated with still images from the film and its production.

Overall

In some ways, ‘Sheba, Baby’ may appear to be a muted reimagining of Coffy: it follows many of the same narrative beats as the earlier picture, but has much less ‘oomph’ owing to the taming down of the violent content that took place towards the end of the blaxploitation era (and would seem to be in response to criticism of the films in some more conservative quarters of society). As David Sheldon notes in the interview on this disc, this may be owing to the fact that the script which evolved into ‘Sheba, Baby’ originated as a treatment for Coffy. Nevertheless, Grier is still on fine form, and she’s supported with some very good second players: Austin Stoker, who starred in John Carpenter’s urban nightmare picture Assault on Precinct 13 the same year as ‘Sheba, Baby’, is a notable example. Whilst ‘Sheba, Baby’ emulates elements of Grier’s earlier films, the picture’s closing sequence was a clear influence on the memorable closing sequence of Quentin Tarantino’s blaxploitation homage Jackie Brown (1997), in which Grier’s air hostess confidently walks out of the life of Robert Forster’s bail bondsman, thus shattering any potential for ongoing romance between the two whilst also asserting Grier’s character’s independence. In some ways, ‘Sheba, Baby’ may appear to be a muted reimagining of Coffy: it follows many of the same narrative beats as the earlier picture, but has much less ‘oomph’ owing to the taming down of the violent content that took place towards the end of the blaxploitation era (and would seem to be in response to criticism of the films in some more conservative quarters of society). As David Sheldon notes in the interview on this disc, this may be owing to the fact that the script which evolved into ‘Sheba, Baby’ originated as a treatment for Coffy. Nevertheless, Grier is still on fine form, and she’s supported with some very good second players: Austin Stoker, who starred in John Carpenter’s urban nightmare picture Assault on Precinct 13 the same year as ‘Sheba, Baby’, is a notable example. Whilst ‘Sheba, Baby’ emulates elements of Grier’s earlier films, the picture’s closing sequence was a clear influence on the memorable closing sequence of Quentin Tarantino’s blaxploitation homage Jackie Brown (1997), in which Grier’s air hostess confidently walks out of the life of Robert Forster’s bail bondsman, thus shattering any potential for ongoing romance between the two whilst also asserting Grier’s character’s independence.

Arrow’s presentation of ‘Sheba, Baby’ is very good indeed, easily equal to their releases of Coffy and Foxy Brown, and includes some very good contextual material. Fans of Grier and blaxploitation pictures generally will find this a very pleasing release. References: Hankin, Kelly, 2002: The Girls in the Back Room: Looking at the Lesbian Bar. University of Minnesota Press Sims, Yvonne D, 2006: Women of Blaxploitation: How the Black Action Film Heroine Changed American Cinema. Gates, Phillippa, 2011: Detecting Women: Gender and the Hollywood Detective Film. State University of New York Pres Lawrence, Novotny, 2007: Blaxploitation Films of the 1970s: Blackness and Genre. London: Routledge Mask, Mia, 2009: Divas on Screen: Black Women in American Film. University of Illinois Press Walker, David et al, 2009: Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Maryland: Scarecrow Press

|

|||||

|