|

|

Kikujiro AKA Kikujirô no natsu (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Third Window Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (28th February 2016). |

|

The Film

Kikujiro (Kitano Takeshi, 1998)  Following his career as a television comedian (or rather, running parallel with this, owing to the continuation of his comedy work throughout his career), Kitano Takeshi moved into filmmaking after his feature directorial debut, the crime drama Violent Cop (1989). This picture about a brutal, vengeful cop, originally to have been directed by Fukasaku Kinji, was transformed under Kitano’s direction from a comedy to a serious drama and represented a new public ‘face’ for Kitano. Kitano’s next few films, in which Kitano both acted and starred, saw him form a strong association with the crime genre, and especially depictions of corrupt cops and yakuzas; to some extent, for international audiences (who predominantly hadn’t been exposed to Kitano’s work as a comedian), this association of Kitano as a star-director working within the crime genre became indelible, thanks to the attention and acclaim that his films Boiling Point (1990), Sonatine (1993) and Hana-bi (1997) received in Britain and the US. In Britain and the US, reviews of those films often compared Kitano’s deadpan performances in them with the work of Clint Eastwood and Robert Mitchum. Meanwhile, Kitano continued to make very different films, more gentle and lyrical, such as A Scene at the Sea (1991), Getting Any? (1994) and Kids Return (1996). Following his career as a television comedian (or rather, running parallel with this, owing to the continuation of his comedy work throughout his career), Kitano Takeshi moved into filmmaking after his feature directorial debut, the crime drama Violent Cop (1989). This picture about a brutal, vengeful cop, originally to have been directed by Fukasaku Kinji, was transformed under Kitano’s direction from a comedy to a serious drama and represented a new public ‘face’ for Kitano. Kitano’s next few films, in which Kitano both acted and starred, saw him form a strong association with the crime genre, and especially depictions of corrupt cops and yakuzas; to some extent, for international audiences (who predominantly hadn’t been exposed to Kitano’s work as a comedian), this association of Kitano as a star-director working within the crime genre became indelible, thanks to the attention and acclaim that his films Boiling Point (1990), Sonatine (1993) and Hana-bi (1997) received in Britain and the US. In Britain and the US, reviews of those films often compared Kitano’s deadpan performances in them with the work of Clint Eastwood and Robert Mitchum. Meanwhile, Kitano continued to make very different films, more gentle and lyrical, such as A Scene at the Sea (1991), Getting Any? (1994) and Kids Return (1996).

Made after the overseas acclaim for his films peaked with Kitano winning the Golden Lion at the 1997 Venice Film Festival for Hana-bi, Kitano’s 1998 picture Kikujiro combines the two aspects of Kitano’s screen persona. The film features Kitano himself as a former yakuza who takes a young boy, Masao, under his wing. The two of them travel together with the intention of visiting Masao’s mother, who when Masao was a baby left the child to be raised by his grandmother. Along the way, Kitano’s character demonstrates a predilection for violence (or rather, threats of violence) as a primary means of achieving his goals, linking the film with Kitano’s ‘serious’ yakuza pictures; but the pair become involved in a series of comic escapades, often ending with slapstick punchlines, whilst exploring the nature of parenthood and the symbolic potency of childhood, linking the picture with Kitano’s non-crime films.  The film opens with nine year old Masao (Sekiguchi Yusuke) and his friend Yuji. They discuss their plans for the summer. An only child, Masao lives with his grandma (Yoshiyuki Kazuko), his mother having left to live in Toyohashi. One day, Masao is saved from bullies by his grandma’s neighbours Kikujiro (Kitano), a former yakuza, and Kikujiro’s wife (Kishimoto Kayoko). Kikujiro and his wife learnt that Masao is planning to travel to Toyohashi to see his mother. Masao’s grandma cannot come with him owing to her work commitments. However, Kikujiro’s wife volunteers her husband for the task of escorting the boy to Toyohashi. ‘My husband loves kids’, she tells Masao’s grandma. Kikujiro and Masao’s trip to Toyohashi finds them encountering a number of different characters, some of them threatening (such as a child molester who threatens Masao before Kikujiro attacks him physically) and others utterly benign (for example, a traveling writer who gives the pair a life in his camper van). The film opens with nine year old Masao (Sekiguchi Yusuke) and his friend Yuji. They discuss their plans for the summer. An only child, Masao lives with his grandma (Yoshiyuki Kazuko), his mother having left to live in Toyohashi. One day, Masao is saved from bullies by his grandma’s neighbours Kikujiro (Kitano), a former yakuza, and Kikujiro’s wife (Kishimoto Kayoko). Kikujiro and his wife learnt that Masao is planning to travel to Toyohashi to see his mother. Masao’s grandma cannot come with him owing to her work commitments. However, Kikujiro’s wife volunteers her husband for the task of escorting the boy to Toyohashi. ‘My husband loves kids’, she tells Masao’s grandma. Kikujiro and Masao’s trip to Toyohashi finds them encountering a number of different characters, some of them threatening (such as a child molester who threatens Masao before Kikujiro attacks him physically) and others utterly benign (for example, a traveling writer who gives the pair a life in his camper van).

However, when Masao and Kikujiro arrive at the address of Masao’s mother, they discover that she has remarried and has a new family. Feeling rejected, Masao wanders to the nearby beach. Trying to cheer the boy up, Kikujiro accosts two bikers, Fatso (The Great Gidayu) and Baldy (Ide Rakkyo), and demands they hand over a lucky charm – a blue angel bell – that one of them has dangled over the handlebars of his motorbike. Giving up hope of reuniting Masao with his mother, Kikujiro instead decides to spend time with the boy, playing; in this, he is aided by the writer and the two bikers, with whom Masao and Kikujiro are reunited. Following this, they part ways with their new friends and return home; their mutual respect and friendship established, Masao and Kikujiro go their separate ways, both of them smiling. As the film begins, Masao is a sad, lonely little boy. In the film’s first sequences, he’s shown with his schoolfriend Yuji, navigating the world of school bullies and walks home from school. Masao feels excluded when Yuji discusses his plans for the summer: Masao, of course, will spend his summer with his grandma. When summer comes, Masao calls for his friend Yuji but gets no response: Yuji’s family have presumably gone on holiday. ‘What a gloomy kid’, Kikujiro comments when meeting Masao for the first time; Kikujiro’s wife informs her husband that Masao has no father and his mother left him in the care of his grandma. However, the irony is that Kikujiro is equally gloomy, and as the narrative moves towards its resolution both Masao and Kikujiro learn to smile.  The film begins with Kikujiro seeking his own pleasure; he’s selfish like a small child. When Kikujiro and his wife stop a group of bullies from stealing Masao’s money near the start of the film, without thinking Kikujiro begins to put the money in his own pocket before his wife reminds her husband that the money belongs to Masao. ‘It’s his, remember’, she snaps at Kikujiro. In response, Kikujiro turns towards the bullies and tells them to ‘Hand over more money or I’ll kill you guys’. However, Kikujiro’s wife stops him: ‘Quit playing gangster’, she orders him. After being ordered by his wife to take Masao to his mother in Toyohashi, Kikujiro first takes the child to a bookmakers, with the aim of gambling with Masao’s money and the money given to Kikujiro by his wife. There, Kikujiro proves himself to be disinterested in Masao, referring to him dryly as ‘you brat’, and caustic towards everyone else: ‘Hey, your head’s blinding me’, Kikujiro complains towards a bald man. The film begins with Kikujiro seeking his own pleasure; he’s selfish like a small child. When Kikujiro and his wife stop a group of bullies from stealing Masao’s money near the start of the film, without thinking Kikujiro begins to put the money in his own pocket before his wife reminds her husband that the money belongs to Masao. ‘It’s his, remember’, she snaps at Kikujiro. In response, Kikujiro turns towards the bullies and tells them to ‘Hand over more money or I’ll kill you guys’. However, Kikujiro’s wife stops him: ‘Quit playing gangster’, she orders him. After being ordered by his wife to take Masao to his mother in Toyohashi, Kikujiro first takes the child to a bookmakers, with the aim of gambling with Masao’s money and the money given to Kikujiro by his wife. There, Kikujiro proves himself to be disinterested in Masao, referring to him dryly as ‘you brat’, and caustic towards everyone else: ‘Hey, your head’s blinding me’, Kikujiro complains towards a bald man.

In these early sequences, Kikujiro isn’t solely defined as childlike through his selfishness: he’s also naïve. Stopping off at a hotel with Masao, he and Masao decide to use the hotel’s swimming pool. (This is where Kikujiro takes off his shirt for the first time, and Masao notices the back tattoo signifying Kikujiro’s past as a gangster.) Much humour is sourced from Kikujiro’s pathetic attempts to swim in this pool, a large inflatable ring around his waist. (Later, he is shown attempting to swim in his sleep.) These events come to a climax with a shot of Masao and Kikujiro in the pool, Kikujiro upside down – only his legs sticking out of the water, owing to the effects of the inflatable ring around his body. Much humour is also sourced from Kikujiro’s insistence on manipulating people into helping he and Masao reach their destination. Stopping off at a truck stop, Kikujiro attempts to use Masao to hitch a lift by encouraging the boy to look glum and unhappy, thus tugging at the heartstrings of the drivers. Later, Kikujiro pretends to be blind in order to hitch a lift; when a driver stops, he tells Kikujiro and Masao that the car is new. ‘New car?’, Kikujiro scoffs, ‘This piece of junk? That stupid decoration’, he asserts, pointing to a decoration hanging from the rearview mirror and thus undermining his performance as a blind man – which results in the driver, angered at Kikujiro’s deception, driving off at speed. The next car to come along hits Kikujiro and knocks him to the ground. The following day, Kikujiro plants a spike in the road in the hope of popping the tyre of a passing car, causing the driver to stop; the technique succeeds in popping the tyre of a passing car, but instead of coming to a halt, it careens off the road and into a ditch. Kikujiro and Masao flee the scene. Shortly afterwards, a car pulls up alongside Kikujiro with Masao already in it. ‘Asking politely is easier’, the boy informs Kikujiro. Kikujiro’s attitude towards Masao becomes more sympathetic following an encounter with a pervert who attempts to molest Masao. Kikujiro arrives on the scene just in time and humiliates the pervert before beating him. Following this, Kikujiro shows a gradual escalation in terms of his desire to protect Masao. Later in the film, after the pair have unsuccessfully attempted to hitch a ride to their destination, Kikujiro watches the sleeping child and asserts, ‘So, he’s just like me’. The similarities between the pair are reinforced when, given a lift by Fatso the biker, Kikujiro pays a visit to a care home later in the film, and is shown into a room where an elderly woman sits staring out of the window. Kikujiro watches her but doesn’t approach her or say a word; he leaves the building silently. The woman, we learn from his conversation with Fatso (in a moment that, characteristic of Kitano’s films, is communicated more by Kikujiro’s silence than by what is said in the dialogue), is Kikujiro’s mother. The reason for their separation isn’t made clear; but the sequence establishes, though Kikujiro’s alienation from his own mother, the similarities between him and Masao.  As Kikujiro and Masao progress on their journey, Masao’s spirits begin to lift owing to the input of the different people they encounter. After unsuccessfully trying to hitch a life from a group of truck drivers, Masao and Kikujiro are picked up by a young couple whose attempts to amuse Masao through juggling and dancing work: the young boy smiles and laughs for what seems to be the first time in the film. Afterwards, Kikujiro and Masao talk about what they will do when they reach their destination. Masao suggests Kikujiro may be allowed to stay with Masao and his mother. ‘Not a good idea’, Kikujiro asserts, ‘Your mum’s pretty, right? I might end up marrying her. Then I’d be your dad [….] You’d have to call me “Daddy”. Try it. Call me “Daddy”… Say it, you little shit’. He and Masao laugh together, consolidating the bond between them. As Kikujiro and Masao progress on their journey, Masao’s spirits begin to lift owing to the input of the different people they encounter. After unsuccessfully trying to hitch a life from a group of truck drivers, Masao and Kikujiro are picked up by a young couple whose attempts to amuse Masao through juggling and dancing work: the young boy smiles and laughs for what seems to be the first time in the film. Afterwards, Kikujiro and Masao talk about what they will do when they reach their destination. Masao suggests Kikujiro may be allowed to stay with Masao and his mother. ‘Not a good idea’, Kikujiro asserts, ‘Your mum’s pretty, right? I might end up marrying her. Then I’d be your dad [….] You’d have to call me “Daddy”. Try it. Call me “Daddy”… Say it, you little shit’. He and Masao laugh together, consolidating the bond between them.

Kikujiro is essentially a road movie, a picaresque story of Masao and Kikujiro’s journey to visit Masao’s mother. The structure is episodic: along the way, the pair encounter a variety of characters and scenarios, resolving these before progressing to their next destination. Leonard Ginsberg suggests that the narrative of Kikujiro alludes to a Japanese literary classic, Jippensha Ikku’s Shank’s Mare, that was originally published in a serialised format during the first years of the nineteenth century (Ginsberg, 2008: 185). Jippensha’s picaresque novel focuses on two men of different ages, Yaji and Kita, who are traveling from Edo to Kyoto along the Tōkaidō road. Ginsberg argues that Kikujiro ‘carries over’ from Jippensha’s novel ‘the demanding egotism of the book’s main character, the spats with vendors, innkeepers and the like, and episodic distractions along the way’ (ibid.). Ginsberg foregrounds the juxtaposition of the ‘bluster’ of Kikujiro and the ‘equanimity’ of Masao, suggesting that ‘it brings to mind a therapeutic relationship’ (ibid.). Quoting Winnicott’s writings about psychotherapy, Ginsberg reminds us that ‘Psychotherapy has to do with two people playing together’, and that the role of the therapist is to move ‘the patient from a state of not being able to play into a state of being able to play’ (Winnicott, quoted in ibid.). Broadly speaking, Kikujiro’s narrative follows this trajectory, with Masao and Kikujiro being, at the start of the film, introverted and sullen creatures who in the film’s closing sequences find themselves able to engage in extended play with the transient writer and the two bikers, Fatso and Baldy.  Gary G Xu has suggested that in learning how to play with Masao, what Kikujiro finds is ultimately not ‘a home […] for the boy but for himself, that is made up of innocent childhood memories’ (Xu, 2007: 128). Gradually, the film reveals ‘the childishness’ that is ‘hidden behind his [Kikujiro’s] awkwardness and clumsiness’ (ibid.). For Ginsberg, Kikujiro also slyly subverts the tropes of Kurosawa’s great Yojimbo (1961), by suggesting through Kikujiro’s learning of how to play with Masao that ‘[t]aking personal responsibility for a child is a more demanding test of character than promptly delivering him to his mother’ (Ginsberg, op cit.: 185). However, Kikujiro’s guidance and tutelage of Masao is both therapeutic and defeatist: as the narrative suggests, Kikujiro can only hope to lighten Masao’s spirits and encourage him to enjoy life, but is able to do nothing to reconcile Masao and his mother or to remedy Masao’s mother’s abandonment of her child (ibid.: 186). Gary G Xu has suggested that in learning how to play with Masao, what Kikujiro finds is ultimately not ‘a home […] for the boy but for himself, that is made up of innocent childhood memories’ (Xu, 2007: 128). Gradually, the film reveals ‘the childishness’ that is ‘hidden behind his [Kikujiro’s] awkwardness and clumsiness’ (ibid.). For Ginsberg, Kikujiro also slyly subverts the tropes of Kurosawa’s great Yojimbo (1961), by suggesting through Kikujiro’s learning of how to play with Masao that ‘[t]aking personal responsibility for a child is a more demanding test of character than promptly delivering him to his mother’ (Ginsberg, op cit.: 185). However, Kikujiro’s guidance and tutelage of Masao is both therapeutic and defeatist: as the narrative suggests, Kikujiro can only hope to lighten Masao’s spirits and encourage him to enjoy life, but is able to do nothing to reconcile Masao and his mother or to remedy Masao’s mother’s abandonment of her child (ibid.: 186).

When Masao and Kikujiro arrive at Toyohashi, turning up at the Masao’s mother’s address, the revelation that Masao’s mother has formed another family which does not include Masao is presented from the child’s perspective. Masao and Kikujiro watch on as Masao’s mother exits the house and says farewell to the man who we presume is her husband and the child who we presume is Masao’s half-sibling. Kikujiro turns around and finds that the dejected, heartbroken Masao has already started to walk away from the scene, turning his back on his dream of being welcomed with open arms by his absent mother. Kikujiro attempts to assuage Masao’s upset by suggesting that they may have reached the wrong address (‘Must be the wrong lady’, Kikujiro says, but given the fact that Masao and Kikujiro have a photograph of Masao’s mother which confirms that the woman in the doorway is indeed her, his words fail to convince the boy.  The structure of the film is loose and episodic, interspersed with images from what could only be described as a photo journal: still frames referencing events that take place in the narrative sequence which follow, with titles that offer a tentative suggestion as to what Masao and Kikujiro might encounter. This, Karen Lury suggests, gives Kikujiro a ‘strangely retrospective temporality’, suggesting ‘a story that has already happened, unfolding as if it were in the present’ (Lury, 2010: 47). Jonathan Rosenbaum has gone so far as to say that ‘the plot of Kikujiro is so minimal and ambiguous it verges on nonexistent’ (Rosenbaum, 2004: 315). Rosenbaum reminds the viewer that the film’s Japanese title translates to ‘The Summer of Kikujiro’, and ‘central to [the film’s] handling of time is that it has a sort of aimless summer drift’ (ibid.). However, the film ‘goes beyond feeling like a “summer movie” and seems suspended in time, so that the picaresque elements could be taking place over three or four days or just as many weeks or months—maybe even years’ (ibid.). It’s a journey that, though the real destinations ‘aren’t that far from one another’, has a ‘mythical’ dimension that makes it feel as if Masao and Kikujiro ‘could be crossing a vast continent’ (ibid.). The structure of the film is loose and episodic, interspersed with images from what could only be described as a photo journal: still frames referencing events that take place in the narrative sequence which follow, with titles that offer a tentative suggestion as to what Masao and Kikujiro might encounter. This, Karen Lury suggests, gives Kikujiro a ‘strangely retrospective temporality’, suggesting ‘a story that has already happened, unfolding as if it were in the present’ (Lury, 2010: 47). Jonathan Rosenbaum has gone so far as to say that ‘the plot of Kikujiro is so minimal and ambiguous it verges on nonexistent’ (Rosenbaum, 2004: 315). Rosenbaum reminds the viewer that the film’s Japanese title translates to ‘The Summer of Kikujiro’, and ‘central to [the film’s] handling of time is that it has a sort of aimless summer drift’ (ibid.). However, the film ‘goes beyond feeling like a “summer movie” and seems suspended in time, so that the picaresque elements could be taking place over three or four days or just as many weeks or months—maybe even years’ (ibid.). It’s a journey that, though the real destinations ‘aren’t that far from one another’, has a ‘mythical’ dimension that makes it feel as if Masao and Kikujiro ‘could be crossing a vast continent’ (ibid.).

As in Sonatine, in particular, Kitano uses the beach which appears partway through the film, following Kikujiro and Masao’s discovery that Masao’s mother has constructed a new family without her oldest son, symbolically (Redmond, 2013: 93). It’s a ‘transitory space’, very different in both appearance and symbolic weight to the city streets in which the film began, where the two outsiders, Masao and Kikujiro, retire to in order ‘to recover from this revelation’ (ibid.). On the beach, Kikujiro demonstrates a strong sense of empathy towards Masao, engaging with (and sympathising with) the boy’s sense of isolation and alienation. Witnessing Masao’s utter desolation after the realisation that his mother abandoned him deliberately, Kikujiro wanders off and presses the bikers to give him their lucky blue angel charm. Kikujiro presents this to Masao with the promise that whenever Masao rings the bell, an angel will appear to assist him. Like a typical child, Masao rings the bell, but of course no angel appears; instead, an animated angel is shown on screen, visible only to the film’s audience rather than present within the diegetic reality of the film. The suggestion is clear: the metonymic relationship that has been drawn between Kikujiro and the good luck charm suggests that Kikujiro is Masao’s ‘angel’. From this point onwards ‘their [Kikujiro and Masao’s] affection for one another will grow but it will not be […] over-sentimentalised or even be simply father/son’ (ibid.). The sequence ends with Kikujiro and Masao having made an angel in the sand; an onscreen title, taken from Masao’s photo journal, declares simply that ‘Mister played with me’.

Video

Running at 121:44 mins, Kikujiro takes up just over 28Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. It’s a 1080p presentation, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The source used for the release is the new 2k restoration of the film conducted by Office Kitano themselves. Running at 121:44 mins, Kikujiro takes up just over 28Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. It’s a 1080p presentation, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The source used for the release is the new 2k restoration of the film conducted by Office Kitano themselves.

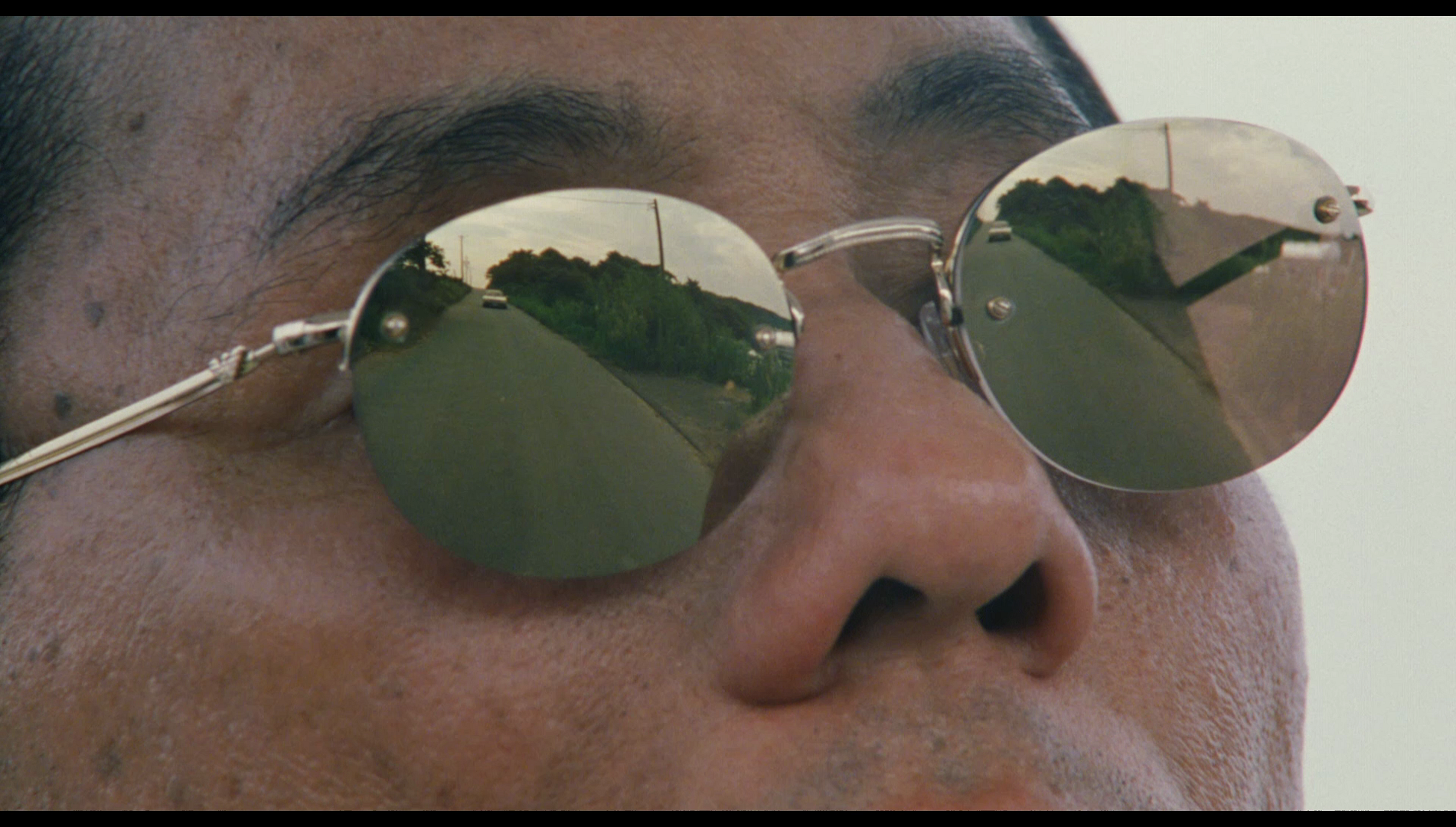

As in a number of Kitano’s other films, the photography within Kikujiro seems as influenced by stills photography as much as by conventional motion picture photography. Aside from the still photographs (which aren’t actually still photographs but simply mirror the static poses and compositions of stills photography – with water still rippling around the participants, for example) which punctuate the narrative, Kitano’s camera frequently pauses as if for reflection with carefully composed shots that are utterly static: the camera is locked down, and the participants are frozen other than slight, very subtle movements (blinking, the sleeves of their shirts blowing in the breeze). The reflective quality is emphasised by the fact that many of these shots are long takes, almost as if someone (Kitano) is pausing the narrative. Colours are stable and consistent in this HD presentation, and the level of detail within the image is a big improvement over the DVD releases of the film. Contrast levels are nicely balanced, with the tonalities between light and dark being defined very well. Some of the night-time sequences feature blacks which seem a little crushed, but this may be a characteristic of the original photography: some of those sequences seem to have been deliberately underexposed by a couple of stops (rather like the photography for John Cassavetes’ Killing of a Chinese Bookie, 1975), perhaps in an attempt to create the impression of deepest night during evening hours whilst also retaining the texture of the more fine-grain slower colour film stocks. Certainly, the whole presentation is handled well by the encoded to disc, which ensures that the picture retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a pleasingly ‘organic’ viewing experience.

NB. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented in DTS-HD MA 2.0 stereo – in Japanese, naturally, with optional English subtitles. One of the most noticeable elements of the film’s audio design is the use of frequent Kitano collaborator Joe Hisaishi’s score. Hisaishi’s music is very ‘Western’ in its application and reminiscent, in many ways, of Ennio Morricone’s scores for Sergio Leone’s westerns all’italiana. The audio track is rich and vibrant, evident from the haunting, bassy sound of Hisaishi’s opening music. The optional English subtitles are easy to read and free of any issues.

Extras

The sole ‘extra’ here is a very good one: Shinozaki Makoto’s Jam Session (92:57), a feature length documentary, mostly shot in an observational style, about the making of Kikujiro. Edited together from over one hundred hours of video footage shot on the set of the picture, this documentary offers some brilliant behind-the-scenes footage of the production interspersed with comments from the cast and crew. Kitano demonstrates dedication to his craft but also insecurity regarding it, something which is contributed to by the critical success of Kikujiro’s predecessor Hana-bi. The urgency of keeping the production of the film to schedule is communicated throughout. There’s some great footage of the Taiwanese filmmaker Hsiao-Hsien Hou visiting Kitano during the film’s post-production phase. It’s a thoroughly excellent documentary that fans of Kitano will find to be essential viewing. The sole ‘extra’ here is a very good one: Shinozaki Makoto’s Jam Session (92:57), a feature length documentary, mostly shot in an observational style, about the making of Kikujiro. Edited together from over one hundred hours of video footage shot on the set of the picture, this documentary offers some brilliant behind-the-scenes footage of the production interspersed with comments from the cast and crew. Kitano demonstrates dedication to his craft but also insecurity regarding it, something which is contributed to by the critical success of Kikujiro’s predecessor Hana-bi. The urgency of keeping the production of the film to schedule is communicated throughout. There’s some great footage of the Taiwanese filmmaker Hsiao-Hsien Hou visiting Kitano during the film’s post-production phase. It’s a thoroughly excellent documentary that fans of Kitano will find to be essential viewing.

Overall

I can remember watching Kitano’s films in the 1990s and being utterly captivated by them: viewings of Violent Cop and Boiling Point on VHS were followed by the chance to watch a screening of Sonatine at my local BFI-funded cinema. The films are utterly enchanting; it was only later that I got the chance to see A Scene at the Sea, Getting Any? And Kids Return, as those films seemed to get much less widespread distribution. On its original release, Hana-bi confirmed my perception of Kitano as a superb filmmaker, and at the time Kikujiro seemed like a strong change of pace for the director-star; however, in retrospect, Kikujiro seems like a deliberate attempt to channel the many aspects of Kitano’s work and his different public faces, combining them into a single film. Certainly, alongside the youth focus of Kitano’s comedies, like Sonatine Kikujiro also contains extended scenes depicting the characters essentially killing time, dispelling boredom and building a sense of community by playing ‘childish’ games: this is what defines the final sequences of the film, in which Masao and Kikujiro are reunited with the bikers and the writer, the group of them role-playing (Kikujiro has Baldy dress up as both an octopus and an extraterrestrial) and playing various games. The film ends on a note of utter, understated warmth. Kikujiro and Masao return home, having been given a lift by the writer. They say farewell to the writer, and Kikujiro tells the boy ’We have to part here too. Let’s do it again some time [….] Take good care of your grandma, eh’. They hug, and go their separate ways, smiling. I can remember watching Kitano’s films in the 1990s and being utterly captivated by them: viewings of Violent Cop and Boiling Point on VHS were followed by the chance to watch a screening of Sonatine at my local BFI-funded cinema. The films are utterly enchanting; it was only later that I got the chance to see A Scene at the Sea, Getting Any? And Kids Return, as those films seemed to get much less widespread distribution. On its original release, Hana-bi confirmed my perception of Kitano as a superb filmmaker, and at the time Kikujiro seemed like a strong change of pace for the director-star; however, in retrospect, Kikujiro seems like a deliberate attempt to channel the many aspects of Kitano’s work and his different public faces, combining them into a single film. Certainly, alongside the youth focus of Kitano’s comedies, like Sonatine Kikujiro also contains extended scenes depicting the characters essentially killing time, dispelling boredom and building a sense of community by playing ‘childish’ games: this is what defines the final sequences of the film, in which Masao and Kikujiro are reunited with the bikers and the writer, the group of them role-playing (Kikujiro has Baldy dress up as both an octopus and an extraterrestrial) and playing various games. The film ends on a note of utter, understated warmth. Kikujiro and Masao return home, having been given a lift by the writer. They say farewell to the writer, and Kikujiro tells the boy ’We have to part here too. Let’s do it again some time [….] Take good care of your grandma, eh’. They hug, and go their separate ways, smiling.

When my son was born, Kikujiro was one of the films that I returned to – not that it’s a model for being a parent, but that the picture establishes a warm relationship between the ‘father’ (Kikujiro) and his symbolic son (Masao) that avoids mawkishness. It’s testament to Kitano’s skill that he can tell this story without stepping into the realm of cloying sentimentality. Whilst Hana-bi, also recently released on Blu-ray by Third Window Films, may be Kitano’s masterwork, Kikujiro is an exceptional film. The presentation of the picture here is very, very good, and the inclusion of the extended documentary about the film’s production is a nice touch. This is a very good release, clearly an improvement over the previously available DVDs, and fans of Kitano will want to own this alongside Third Window’s new Blu-ray release of Hana-bi (and the upcoming release of Kitano’s Dolls). References: Ginsberg, Leonard, 2008: Rhapsody on a Film by Kurosawa. London: Trafford Publishing Lury, Karen, 2010: The Child in Time: Tears, Fears and Fairytales. London: I B Tauris Redmond, Sean, 2013: The Cinema of Takeshi Kitano: Flowering Blood. London: Wallflower Press Rosenbaum, Jonathan, 2004: Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. London: Johns Hopkins University Press Xu, Gary G, 2007: Sinascape: Contemporary Chinese Cinema. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

|

|||||

|