|

|

The Film

Killer Dames: Two Gothic Chillers by Emilio P. Miraglia  The thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) is remarkably diverse, a fact that is often sidelined in English-language criticism of Italian thrillers and the fan discourse that surrounds them. With its major period often claimed to be sparked by Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) in 1964 and its popularity with Italian audiences not really declining until the mid/late-1980s, the ‘boom’ period of the thrilling all’italiana saw the production of a wide variety of thrillers that were all defined by the curious flavour or ‘Italian-style’ that the name of this subgroup of films suggests – much like the western all’italiana (Italian-style Western) or poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police film), to cite two roughly contemporaneous subgenres. However, as fans have embraced and come to use the originally pejorative label ‘Spaghetti Western’ to denote the western all’italiana, English-speaking fans of the thrilling all’italiana have demonstrated a tendency to use the label giallo to denote these Italian-made thrillers of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s; though in truth, to Italian audiences a giallo is a thriller of any origin, and for Italian cinephiles the label may be applied as much to a Hitchcock thriller or a film such as John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) as to Italian thrillers such as Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino. As Philippe Met suggests, approaches to understanding the giallo/thrilling all’italiana are complicated by ‘existing discrepancies of a semantic or taxonomic nature’ (2006: 196). Met suggests that there is irony within the fact that within Italy, ‘in the very country in which it [the giallo/thrilling all’italiana] originated, the all’italiana [Italian-style] specificity of the genre’ is largely ‘subsumed by […] a much broader understanding of the giallo designation as coextensive with crime cinema’ more generally, ‘cutting across national boundaries and the typological spectrum’; whilst in Britain and America, on the other hand, the giallo is seen as an exclusively Italian product, to the extent that debates exist as to whether ‘one can viably and legitimately stretch it to create an “American giallo”’, for example (ibid.). Thus it is impossible to overstate how significant the ‘Italian-style’ of the Italian-language designator (thrilling all’italiana, or sometimes giallo all’italiana) is. The thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) is remarkably diverse, a fact that is often sidelined in English-language criticism of Italian thrillers and the fan discourse that surrounds them. With its major period often claimed to be sparked by Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) in 1964 and its popularity with Italian audiences not really declining until the mid/late-1980s, the ‘boom’ period of the thrilling all’italiana saw the production of a wide variety of thrillers that were all defined by the curious flavour or ‘Italian-style’ that the name of this subgroup of films suggests – much like the western all’italiana (Italian-style Western) or poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police film), to cite two roughly contemporaneous subgenres. However, as fans have embraced and come to use the originally pejorative label ‘Spaghetti Western’ to denote the western all’italiana, English-speaking fans of the thrilling all’italiana have demonstrated a tendency to use the label giallo to denote these Italian-made thrillers of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s; though in truth, to Italian audiences a giallo is a thriller of any origin, and for Italian cinephiles the label may be applied as much to a Hitchcock thriller or a film such as John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) as to Italian thrillers such as Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino. As Philippe Met suggests, approaches to understanding the giallo/thrilling all’italiana are complicated by ‘existing discrepancies of a semantic or taxonomic nature’ (2006: 196). Met suggests that there is irony within the fact that within Italy, ‘in the very country in which it [the giallo/thrilling all’italiana] originated, the all’italiana [Italian-style] specificity of the genre’ is largely ‘subsumed by […] a much broader understanding of the giallo designation as coextensive with crime cinema’ more generally, ‘cutting across national boundaries and the typological spectrum’; whilst in Britain and America, on the other hand, the giallo is seen as an exclusively Italian product, to the extent that debates exist as to whether ‘one can viably and legitimately stretch it to create an “American giallo”’, for example (ibid.). Thus it is impossible to overstate how significant the ‘Italian-style’ of the Italian-language designator (thrilling all’italiana, or sometimes giallo all’italiana) is.

That ‘Italian-style’, however, is notoriously nebulous. The Italian thrillers themselves include Edgar Wallace adaptations (Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange?/What Have You Done to Solange?, 1972), paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (1951), and ‘impure’ hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all’italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films).  The fearsome reputation of Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino - its ‘bodycount’ approach to narrative; its emphasis on the electrocardiogram thrill of the sadistic murder setpiece – overshadows many of the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that followed it, and was consolidated by Dario Argento’s run of Italian thrillers that began with L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970) and encapsulated a similar ethos to the Bava picture. Consequently, for non-Italian audiences the thrilling all’italiana seems to be defined by the more delirious examples of the Italian-made thriller: the more baroque, vivid and explicit films such as those made by Argento or the metropolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ thrillers of Sergio Martino (La Morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972; please see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of that film here), often dominated by a whodunit structure and, within their iconography, the figure of the black-clad, black-gloved assassin who perpetrates excruciating torment upon vulnerable women; the ‘look’ of the killers in these films is usually sourced from Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino, which Mikel Koven suggests ‘borrowed’ the appearance of its murderer from George Pollock’s Murder She Said (1961) (Koven, 2006: 4). This get-up would come to be associated with the more extravagant examples of the thrilling all’italliana via its appearance in a number of Argento’s films, beginning with L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, and numerous other Italian thrilling films of the 1970s, such as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972) and Paolo Cavara’s La tarantola dal ventre nero (The Black Belly of the Tarantula, 1971), to cite but two examples. The fearsome reputation of Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino - its ‘bodycount’ approach to narrative; its emphasis on the electrocardiogram thrill of the sadistic murder setpiece – overshadows many of the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that followed it, and was consolidated by Dario Argento’s run of Italian thrillers that began with L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970) and encapsulated a similar ethos to the Bava picture. Consequently, for non-Italian audiences the thrilling all’italiana seems to be defined by the more delirious examples of the Italian-made thriller: the more baroque, vivid and explicit films such as those made by Argento or the metropolitan ‘woman-in-peril’ thrillers of Sergio Martino (La Morte accarezza a mezzanotte/Death Walks at Midnight, 1972; please see our review of Arrow’s Blu-ray release of that film here), often dominated by a whodunit structure and, within their iconography, the figure of the black-clad, black-gloved assassin who perpetrates excruciating torment upon vulnerable women; the ‘look’ of the killers in these films is usually sourced from Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino, which Mikel Koven suggests ‘borrowed’ the appearance of its murderer from George Pollock’s Murder She Said (1961) (Koven, 2006: 4). This get-up would come to be associated with the more extravagant examples of the thrilling all’italliana via its appearance in a number of Argento’s films, beginning with L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, and numerous other Italian thrilling films of the 1970s, such as Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris, 1972) and Paolo Cavara’s La tarantola dal ventre nero (The Black Belly of the Tarantula, 1971), to cite but two examples.

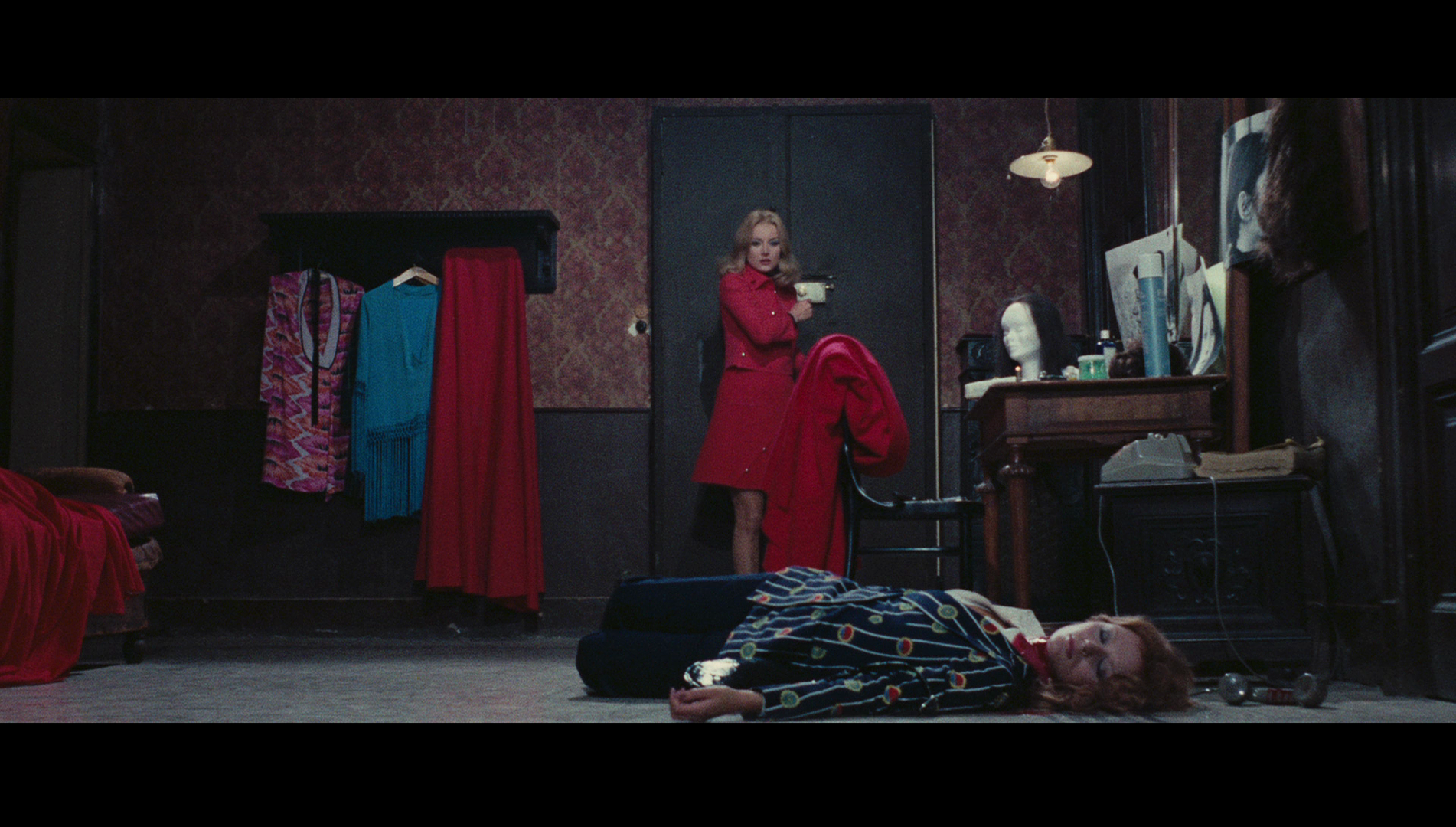

The two films in this set, Emilio P Miraglia’s La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba (The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave, Emilio P Miraglia, 1971) and La dama rossa uccide sette volte (The Red Queen Kills 7 Times, 1972), feature elements of the ‘woman-in-peril film but up the ante in terms of their use of the iconography of the Gothic horror film. Peter Bondanella notes that the second film, La dama rosse uccide sette volte, ‘combines the completely contemporary environment of a large German city, the couture of a German fashion house called Springe, and the Gothic atmosphere of a mysterious castle filled with a legendary ghost, the Red Queen’ (Bondanella, 2009: 399). The film thus ‘marries the world of haute couture with Gothic horror’ (ibid.).  The first film, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba features a similarly Gothic sense of place. Set in England, most of the film takes place in the large, rundown country retreat (referred to in the dialogue as a castle, but it’s more like a manor house) belonging to Lord Alan Victor Cunningham (Antonio De Teffè/Anthony Steffen). Alan has recently been released from the care of his friend, psychiatrist Richard Timberlane (Giacomo Rossi Stuart), who manages the Timberland Psychiatric Clinic. Alan’s life has entered a strange kind of stasis since the death of his wife Evelyn. Allowing his family home to go to ruin, Alan retreats into his own living quarters within the house and the adjoining torture chamber, to which he lures young women before assaulting and killing them. The first film, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba features a similarly Gothic sense of place. Set in England, most of the film takes place in the large, rundown country retreat (referred to in the dialogue as a castle, but it’s more like a manor house) belonging to Lord Alan Victor Cunningham (Antonio De Teffè/Anthony Steffen). Alan has recently been released from the care of his friend, psychiatrist Richard Timberlane (Giacomo Rossi Stuart), who manages the Timberland Psychiatric Clinic. Alan’s life has entered a strange kind of stasis since the death of his wife Evelyn. Allowing his family home to go to ruin, Alan retreats into his own living quarters within the house and the adjoining torture chamber, to which he lures young women before assaulting and killing them.

Alan’s secret is known to Albert (Roberto Maldera), Evelyn’s brother and the gamekeeper. Albert subjects Alan to blackmail. Alan is also joined on the estate by his Aunt Agatha (Joan C Davies) and cousin George (Enzo Tarascio/Rod Murdock). Agatha and George are counterculture types who arrange a séance with the aim of enabling Alan to contact Evelyn from beyond the grave, thus ending the ‘attacks’ he experiences. Meanwhile, Richard attempts to cure Alan in a less mystical manner. George takes Alan into town and introduces him to a stripper, Susan (Erika Blanc). Taken with the red-haired Susan, Alan takes her back to his house and lures her into the torture chamber. Susan, however, seems to escape. Later, he meets another woman, a blonde named Gladys (Marina Malfatti). Smitten with her, Alan asks her to marry him. Gladys and Alan are married. After a series of strange events, Gladys explores the Cunningham family crypt and discovers Evelyn’s coffin to be empty. Meanwhile, Albert and Aunt Agatha are murdered in grisly ways. As the ghost of Evelyn seems to haunt Alan, he is driven into an increasingly helpless frenzy.  As with many examples of the thrilling all’italiana, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba features some heavily fetishistic imagery. Alan, the film’s protagonist, is fixated on women with red hair: red hair drives him into a frenzy, precipitating what are referred to rather obliquely (and rather reductively) as his ‘attacks’. (Aunt Agatha purposefully hires blonde maids so as to avoid leading Alan into one of his attacks.) During these attacks, Alan is driven into a murderous frenzy, luring women into his house, seducing them and enticing them into a torture chamber that is deep within the Cunningham country manor. There, he teases them before asking them to dress in a specific pair of thigh-high go-go boots (another fetish object within the film). After restraining them – playfully at first – he whips them before branding them with a hot iron and murdering them. In an early sequence, Alan drives a prostitute to his home; in his car, he suddenly pulls on her hair. ‘Are you crazy?’, the young woman asks. ‘I’m sorry. I thought it was a wig’, Alan replies unconvincingly. In the torture chamber, the young woman accedes to Alan’s demands, putting on the go-go boots and allowing Alan to tease her with the whip; ‘A lot of men like strange games’, she observes. Alan whips her cruelly, the violence seeming to offer him a form of catharsis: ‘I won’t be the victim this time’, he declares before commencing with the whipping, ‘I won’t be a slave for anyone’. Afterwards, he begs the prostitute for forgiveness, calling her by his dead wife’s name: ‘I know, Evelyn, it’s my fault that you suffered, but it’s over now’. For his part, Richard tells Alan that if he can leave Evelyn (the object of his fetish) behind, he may be able to live a comparatively ‘normal’ life: suggesting that ‘If you don’t control yourself, you could end up in a bad way’, Richard informs Alan that ‘You could be normal again, if you wanted to. Marry again. Forget Evelyn’. ‘That’s the problem, Richard’, Alan responds, ‘I can’t forget her. I’m obsessed with her’. As with many examples of the thrilling all’italiana, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba features some heavily fetishistic imagery. Alan, the film’s protagonist, is fixated on women with red hair: red hair drives him into a frenzy, precipitating what are referred to rather obliquely (and rather reductively) as his ‘attacks’. (Aunt Agatha purposefully hires blonde maids so as to avoid leading Alan into one of his attacks.) During these attacks, Alan is driven into a murderous frenzy, luring women into his house, seducing them and enticing them into a torture chamber that is deep within the Cunningham country manor. There, he teases them before asking them to dress in a specific pair of thigh-high go-go boots (another fetish object within the film). After restraining them – playfully at first – he whips them before branding them with a hot iron and murdering them. In an early sequence, Alan drives a prostitute to his home; in his car, he suddenly pulls on her hair. ‘Are you crazy?’, the young woman asks. ‘I’m sorry. I thought it was a wig’, Alan replies unconvincingly. In the torture chamber, the young woman accedes to Alan’s demands, putting on the go-go boots and allowing Alan to tease her with the whip; ‘A lot of men like strange games’, she observes. Alan whips her cruelly, the violence seeming to offer him a form of catharsis: ‘I won’t be the victim this time’, he declares before commencing with the whipping, ‘I won’t be a slave for anyone’. Afterwards, he begs the prostitute for forgiveness, calling her by his dead wife’s name: ‘I know, Evelyn, it’s my fault that you suffered, but it’s over now’. For his part, Richard tells Alan that if he can leave Evelyn (the object of his fetish) behind, he may be able to live a comparatively ‘normal’ life: suggesting that ‘If you don’t control yourself, you could end up in a bad way’, Richard informs Alan that ‘You could be normal again, if you wanted to. Marry again. Forget Evelyn’. ‘That’s the problem, Richard’, Alan responds, ‘I can’t forget her. I’m obsessed with her’.

Like many of the thrilling all’italiana films, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba underscores its theme of identity and performance through a highly theatrical nightclub scene. Here, it’s a nightclub scene that introduces Susan. With iconography that reinforces the necrophilic fetishism that dominates Alan (his fixation on the dead Evelyn) – and foreshadows Alan’s later vision of Evelyn climbing out of her own coffin, which is entombed within the Cunningham family crypt – Susan is carried onto the stage of the nightclub in a coffin, out of which she climbs seductively.  Like much Gothic fiction, Miraglia’s film makes strong symbolic use of the house which is the focus for the majority of the film’s narrative. (Only a handful of scenes take place away from Cunningham’s house and its grounds, to be truthful.) Much of the building is in a state of disrepair and dereliction, though Alan’s rooms are rather swanky, being decorated in a Baroque fashion and with all the mod cons (a swish television, for example). The only other area of the house which seems to be well-cared for is the torture chamber, an inner sanctum in which Alan has perfectly preserved examples of medieval torture instruments. If the house is a symbol of the self, or one’s heritage (as in Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, for example), the symbolism of the Cunningham family home seems obvious. When Alan meets a new woman, he forces them to tread through the cobwebs of the majority of the house (representing his neglect of his title and role) to his private, internal retreat which is decorated in a combination of Baroque designs symbolic of the past and mod cons that represent the present (and in which resides the painted portrait of Evelyn that is the core of Alan’s fixation), and finally he takes them to the airless, windowless torture chamber – symbolic of his perverse, concealed desires – in which he sadistically whips, brands and murders them. When Alan leads his first victim, the prostitute mentioned above, into the house, she declares that ‘This is a castle’. Alan corrects her: ‘It was a castle. Now it’s turning into a ruin’. When the woman sees Alan’s well-maintained living quarters, she remarks in surprise, ‘Why are you letting the rest go to ruin?’ Alan tells her simply that ‘The house is full of bad memories’ for him. Like much Gothic fiction, Miraglia’s film makes strong symbolic use of the house which is the focus for the majority of the film’s narrative. (Only a handful of scenes take place away from Cunningham’s house and its grounds, to be truthful.) Much of the building is in a state of disrepair and dereliction, though Alan’s rooms are rather swanky, being decorated in a Baroque fashion and with all the mod cons (a swish television, for example). The only other area of the house which seems to be well-cared for is the torture chamber, an inner sanctum in which Alan has perfectly preserved examples of medieval torture instruments. If the house is a symbol of the self, or one’s heritage (as in Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, for example), the symbolism of the Cunningham family home seems obvious. When Alan meets a new woman, he forces them to tread through the cobwebs of the majority of the house (representing his neglect of his title and role) to his private, internal retreat which is decorated in a combination of Baroque designs symbolic of the past and mod cons that represent the present (and in which resides the painted portrait of Evelyn that is the core of Alan’s fixation), and finally he takes them to the airless, windowless torture chamber – symbolic of his perverse, concealed desires – in which he sadistically whips, brands and murders them. When Alan leads his first victim, the prostitute mentioned above, into the house, she declares that ‘This is a castle’. Alan corrects her: ‘It was a castle. Now it’s turning into a ruin’. When the woman sees Alan’s well-maintained living quarters, she remarks in surprise, ‘Why are you letting the rest go to ruin?’ Alan tells her simply that ‘The house is full of bad memories’ for him.

Many of the roughly contemporaneous ‘woman-in-peril’ examples of the thrilling all’italiana – such as Luciano Ercoli’s La Morte accarezza a mezzanotte or Luigi Bazzoni’s Le orme (Footprints, 1975) – follow the model set by American films noir such as Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1947), Julie (Andrew L Stone, 1956), The House on Telegraph Hill (Robert Wise, 1951) and The Dark Corner (Henry Hathaway, 1946). These are films which focus on women who find themselves threatened, often in domestic settings, and whose persecution leads them to being perceived as paranoid and hysterical – by both the men in the film and, potentially, the film’s audience itself. These women are frequently shown to be in relationships with men who are either explicitly trying to kill them (in the manner of Bluebeard) or who seem to be manipulating events in order to use the women as patsies in a much grander scheme. In the 1970s, this narrative mode would arguably culminate in Richard Brooks’ 1977 picture Looking for Mr Goodbar, an adaptation of Judith Rossner’s 1975 novel of the same title. Many of the roughly contemporaneous ‘woman-in-peril’ examples of the thrilling all’italiana – such as Luciano Ercoli’s La Morte accarezza a mezzanotte or Luigi Bazzoni’s Le orme (Footprints, 1975) – follow the model set by American films noir such as Fritz Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door (1947), Julie (Andrew L Stone, 1956), The House on Telegraph Hill (Robert Wise, 1951) and The Dark Corner (Henry Hathaway, 1946). These are films which focus on women who find themselves threatened, often in domestic settings, and whose persecution leads them to being perceived as paranoid and hysterical – by both the men in the film and, potentially, the film’s audience itself. These women are frequently shown to be in relationships with men who are either explicitly trying to kill them (in the manner of Bluebeard) or who seem to be manipulating events in order to use the women as patsies in a much grander scheme. In the 1970s, this narrative mode would arguably culminate in Richard Brooks’ 1977 picture Looking for Mr Goodbar, an adaptation of Judith Rossner’s 1975 novel of the same title.

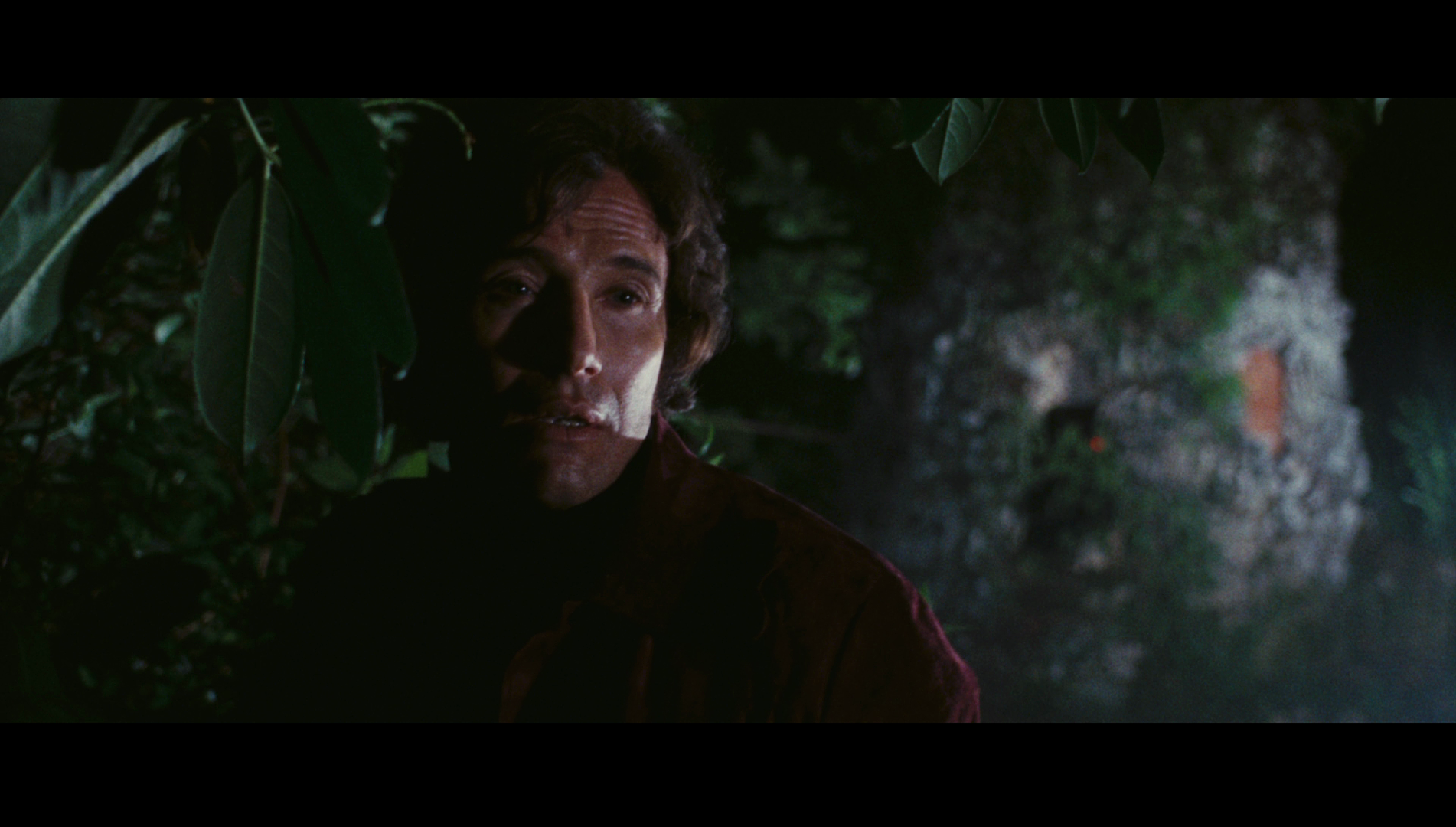

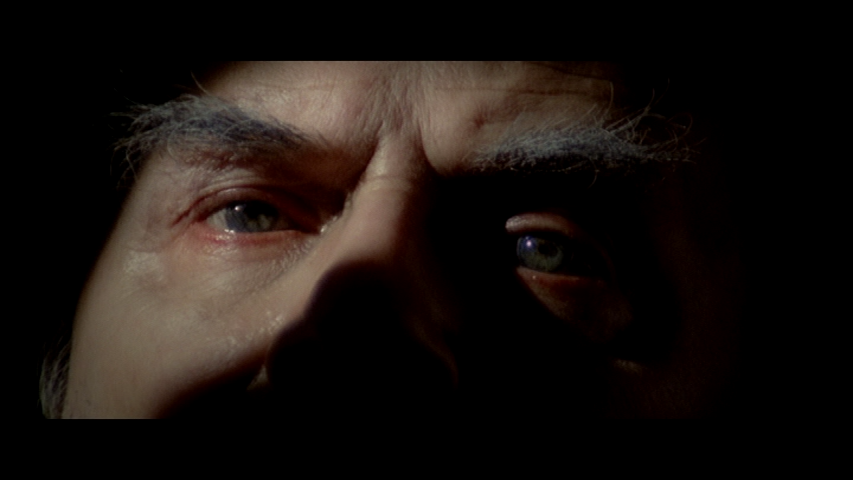

The woman-in-peril form is often cited as having its roots in Ann Radcliffe’s archetypal Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), in which the protagonist Emily St Aubert is forced to live with her aunt, Madame Cheron. Madame Cheron’s husband, Montoni, tries to force Emily to marry his friend, Count Morano. Moving his wife and Emily to his castle of Udolpho, Montoni attempts to railroad Madame Cheron into making him, instead of Emily, her sole heir; when Madame Cheron dies owing to a grave illness and Emily inherits her aunt’s wealth, Emily finds herself the object of a series of frightening events that take place within the castle of Udolpho. Radcliffe’s novel is the model for many subsequent woman-in-peril narratives, from novels like Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca(1938) and plays such as Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light (1938) to the ‘woman-in-peril’ strand within the thrilling all’italiana. The title of Hamilton’s play of course led to the term ‘gaslighting’ being used to denote the phenomenon (in both fiction and in real life) in which a typically male antagonist attempts to manipulate his lover into believing she is insane, and to encourage others to perceive her as such. Like the woman-in-peril films noir, perhaps owing to its roots in one of the defining Gothic novels (The Mysteries of Udolpho), the woman-in-peril thrilling all’italiana often has Gothic overtones and a strong Freudian framework – including a focus on dreams and dreamlike imagery.  La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba is a ‘woman-in-peril’ example of the form in all but one way: it features a male protagonist. From the opening sequence onwards, Alan is ‘feminised’ by the gaze of the camera. The opening sequence shows him in the grip of a hysteria that is usually reserved in cinema for female characters. In the midst of an attack of psychosis (communicated to the audience via point-of-view shots which seem to feature Vaseline on the lens, and the use of discordant voices and other sounds on the audio track), Alan attempts to escape from the mental institute that is presided over by Richard. Alan is pursued through the grounds of the institute by two orderlies. The revelation that Alan’s mental condition was precipitated by the fact that Evelyn and her lover made him a cuckold further serves to feminise him, stripping him of his masculine authority as both the film’s protagonist and a man of reputation and social standing. Finally, the film’s plot itself revolves around the attempt to drive Alan insane in order to attain the family home, worth three million pounds, and Alan’s title as Lord Cunningham; at its heart, it’s really a ‘gaslighting’ plot with a male victim rather than the female victims of most gaslighting narratives in cinema. (Richard Franklin’s Psycho II, 1983, in which Vera Miles’ Lila attempts to drive Norman Bates – recently released from a mental institution – insane is another example of a film which features a ‘gaslighting’ plot in which the victim is a male.) La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba is a ‘woman-in-peril’ example of the form in all but one way: it features a male protagonist. From the opening sequence onwards, Alan is ‘feminised’ by the gaze of the camera. The opening sequence shows him in the grip of a hysteria that is usually reserved in cinema for female characters. In the midst of an attack of psychosis (communicated to the audience via point-of-view shots which seem to feature Vaseline on the lens, and the use of discordant voices and other sounds on the audio track), Alan attempts to escape from the mental institute that is presided over by Richard. Alan is pursued through the grounds of the institute by two orderlies. The revelation that Alan’s mental condition was precipitated by the fact that Evelyn and her lover made him a cuckold further serves to feminise him, stripping him of his masculine authority as both the film’s protagonist and a man of reputation and social standing. Finally, the film’s plot itself revolves around the attempt to drive Alan insane in order to attain the family home, worth three million pounds, and Alan’s title as Lord Cunningham; at its heart, it’s really a ‘gaslighting’ plot with a male victim rather than the female victims of most gaslighting narratives in cinema. (Richard Franklin’s Psycho II, 1983, in which Vera Miles’ Lila attempts to drive Norman Bates – recently released from a mental institution – insane is another example of a film which features a ‘gaslighting’ plot in which the victim is a male.)

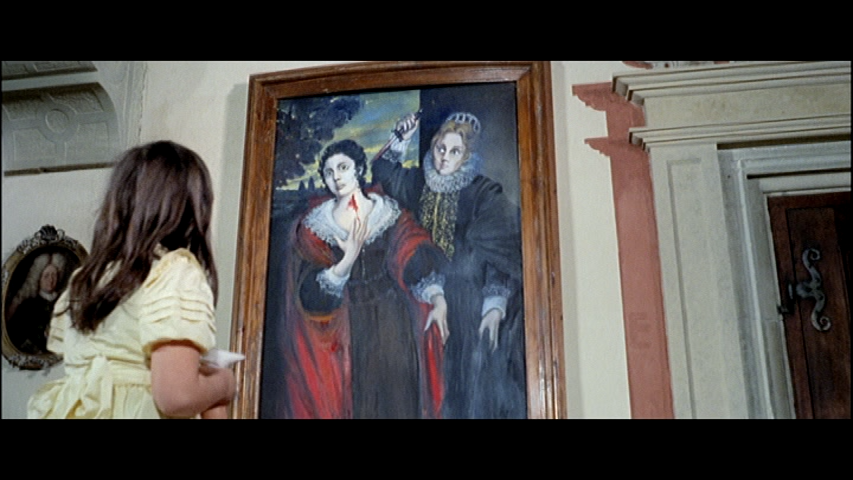

Hitchcock’s original Psycho (1960) is a relevant reference point here, as in some ways Alan displays some parallels with Norman Bates, in terms of his association with a partially-derelict house, his cruel murders of women during his ‘attacks’ and his fixation on a dead woman whose image dominates his life and who appears to come back from the dead (though, of course, Evelyn is/was Alan’s wife rather than his mother). As Hitchcock’s film is dominated by the dual absence-presence of Norman’s mother, La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba is dominated by the absence of Evelyn, who throughout the narrative seems set to make a ‘return’ from beyond the grave. Evelyn’s portrait is the focal point of Alan’s living quarters, an object of necrophilic fetishism to which Alan – and the camera – returns again and again, until Alan commands Gladys to destroy it. (The dominance of this portrait, of course, recalls Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.) For a while, the film seems to invest some stock in the supernatural, with Alan participating in a séance organised by Aunt Agatha to contact Evelyn – with the hope that such contact will stop his ‘attacks’. Associated with Aunt Agatha and cousin George, both of whom are connected via their dress and behaviour with the counterculture, this unorthodox approach is juxtaposed with Richard’s focus on psychiatry as a ‘cure’ to Alan’s behaviour.  Miraglia’s La dama rossa uccide sette volte begins with two children, the sisters Kitty and Eveline, squabbling in the grounds of a castle. Their argument centres over a doll belonging to Kitty, which Eveline has taken and is using to taunt her sister. Their argument is carried inside, where their elderly grandfather Tobias Wildenbrück (Rudolf Schindler) attempts to stop them from arguing with one another. Eveline becomes fascinated by a painting which is a depiction of the legend of the Red Queen and Black Queen; these were ancestors of the Wildenbrück family, and the painting shows the Red Queen murdering the Black Queen. Tobias tells the girls the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, informing them that it is said that the act of sororicide that the painting depicts is doomed to be repeated by a pair of sisters within the Wildenbrück family once every century. Miraglia’s La dama rossa uccide sette volte begins with two children, the sisters Kitty and Eveline, squabbling in the grounds of a castle. Their argument centres over a doll belonging to Kitty, which Eveline has taken and is using to taunt her sister. Their argument is carried inside, where their elderly grandfather Tobias Wildenbrück (Rudolf Schindler) attempts to stop them from arguing with one another. Eveline becomes fascinated by a painting which is a depiction of the legend of the Red Queen and Black Queen; these were ancestors of the Wildenbrück family, and the painting shows the Red Queen murdering the Black Queen. Tobias tells the girls the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, informing them that it is said that the act of sororicide that the painting depicts is doomed to be repeated by a pair of sisters within the Wildenbrück family once every century.

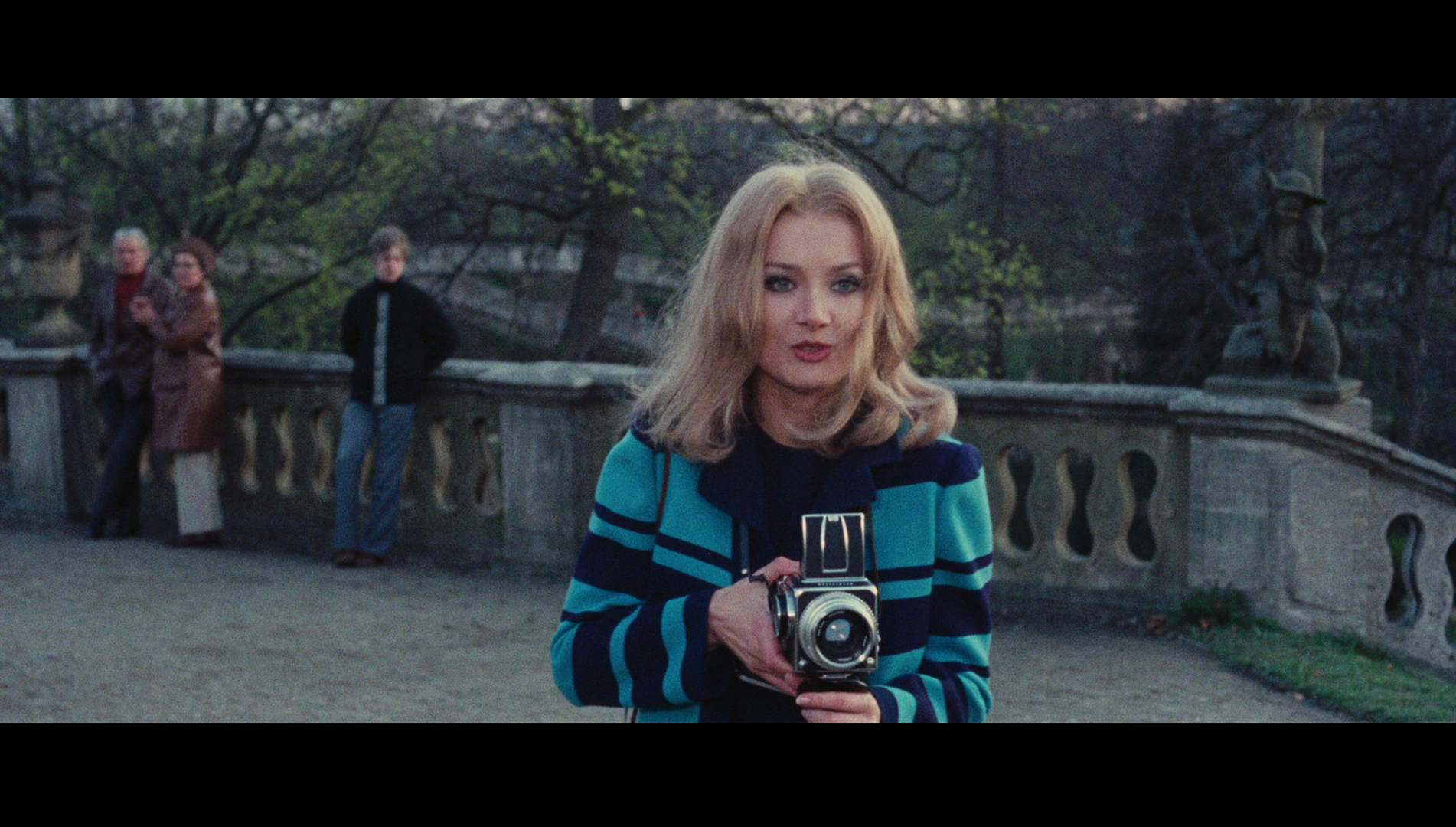

From here, the narrative moves to the present day, 1972. Tobias is visited in the night by the Red Queen and dies, apparently from the shock. Now an adult, Kitty (Barbara Bouchet), a photographer for a German fashion house, is called back to the family castle for her grandfather’s funeral and the reading of his will. She is met by her other sister Franzisca (Marina Malfatti) and Franzisca’s lover Herbert Zieler (Nino Korda). Eveline’s absence is a mystery, until it is revealed that during a squabble, Kitty apparently killed Eveline accidentally, and Franzisca and Herbert helped to cover up Eveline’s demise. However, Herbert claims to have seen ‘the Red Queen in the park’ and she ‘had Eveline’s face’. Eveline’s lover Martin (Ugo Pagliali) is married; Martin’s wife Elizabeth is incarcerated within a psychiatric hospital, where she claims to be visited nightly by Eveline. The owner of the fashion house, Hans (Bruno Bertocci), is a man of dubious sexual tastes who, whilst picking up a prostitute with his lover Lulu (Sybil Danning), is murdered by the Red Queen. Martin becomes the new manager of the fashion company; this fact leads to Martin being the chief suspect in the eyes of Inspector Tolman (Marino Mase), who is investigating Hans’ murder. Kitty receives a telephone call from Eveline, claiming that ‘I’ve come back from my long journey. I’m back, Kitty, and I’m going to kill you’. As the murders committed by the Red Queen escalate, Kitty also finds herself approached by Eveline’s lover Peter (Fabrizio Moresco); a drug addict, Peter subjects Kitty to blackmail before sexually assaulting her prior to becoming one of the Red Queen’s victims. The film builds towards a climax in the castle, the source of the legend, where Kitty attempts to identify who exactly is masquerading as the Red Queen.  As Richard Dyer suggests, the very title of La dama rossa uccide sette volte suggests repetition and a cycle of violence (… ‘Kills Seven Times’) (Dyer, 2015: 40). The story of the Red Queen the Black Queen and their female descendants, who it is said are fated to re-enact the actions of their ancestors, carries with it a sense of fatalism, ritualism and repetition. Here, the painting of the Red Queen and the Black Queen has a similar function to the portrait of Evelyn in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. The painting is in Tobias’ study, to which the young Kitty and Eveline return following their spat in the garden, has a seemingly supernatural power over the girls; the mere sight of it seems to fascinate Eveline and goad her to violence. The girls’ relationship with the painting is marked form their first encounter with it ‘I’m the Red Queen; Kitty’s the Black Queen’, Eveline declares upon seeing the painting, then after gazing at it for a while stabs and decapitates Kitty’s beloved doll, telling Tobias ‘When I saw that picture, I felt something inside of me’. In some ways, this could be interpreted as a satirical approach to the idea that works of art may inspire mimetic acts of violence. Certainly, even if one does not interpret the film’s use of the painting in this way, the fascination exerted by the painting upon those around it connects the film with other examples of the thrilling all’italiana that explore the connections between art and violence, and the impact that works of art have upon their audience; this is a motif that runs throughout films like Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono and also a number of Dario Argento’s thrilling pictures, for example, from Tenebre (1982) and Opera (1989) to La sindrome di Stendhal (The Stendhal Syndrome, 1996). Many of the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that explore this theme have a strong sense of fatalism to them, often using works of art as an index of a past crime that has repercussions in the present (eg, the childish drawing of the murder that is central to Argento’s Profondo rosso/Deep Red, 1975). In La casa dalle finestre che ridono, for example, the fresco that Stefano (Lino Capolicchio) has been commissioned to restore depicts the martyring of St Sebastian, and as the narrative progresses Stefano comes to realise that the fresco was painted from a life study and this comes with an awareness that Stefano’s own life is in danger. La dama rossa ucchide sette volte takes a similar approach: the painting is connected to the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, which it is said is doomed to be repeated once every century. As Richard Dyer suggests, the very title of La dama rossa uccide sette volte suggests repetition and a cycle of violence (… ‘Kills Seven Times’) (Dyer, 2015: 40). The story of the Red Queen the Black Queen and their female descendants, who it is said are fated to re-enact the actions of their ancestors, carries with it a sense of fatalism, ritualism and repetition. Here, the painting of the Red Queen and the Black Queen has a similar function to the portrait of Evelyn in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. The painting is in Tobias’ study, to which the young Kitty and Eveline return following their spat in the garden, has a seemingly supernatural power over the girls; the mere sight of it seems to fascinate Eveline and goad her to violence. The girls’ relationship with the painting is marked form their first encounter with it ‘I’m the Red Queen; Kitty’s the Black Queen’, Eveline declares upon seeing the painting, then after gazing at it for a while stabs and decapitates Kitty’s beloved doll, telling Tobias ‘When I saw that picture, I felt something inside of me’. In some ways, this could be interpreted as a satirical approach to the idea that works of art may inspire mimetic acts of violence. Certainly, even if one does not interpret the film’s use of the painting in this way, the fascination exerted by the painting upon those around it connects the film with other examples of the thrilling all’italiana that explore the connections between art and violence, and the impact that works of art have upon their audience; this is a motif that runs throughout films like Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono and also a number of Dario Argento’s thrilling pictures, for example, from Tenebre (1982) and Opera (1989) to La sindrome di Stendhal (The Stendhal Syndrome, 1996). Many of the examples of the thrilling all’italiana that explore this theme have a strong sense of fatalism to them, often using works of art as an index of a past crime that has repercussions in the present (eg, the childish drawing of the murder that is central to Argento’s Profondo rosso/Deep Red, 1975). In La casa dalle finestre che ridono, for example, the fresco that Stefano (Lino Capolicchio) has been commissioned to restore depicts the martyring of St Sebastian, and as the narrative progresses Stefano comes to realise that the fresco was painted from a life study and this comes with an awareness that Stefano’s own life is in danger. La dama rossa ucchide sette volte takes a similar approach: the painting is connected to the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, which it is said is doomed to be repeated once every century.

The story told to Eveline and Kitty by Tobias is fatalistic, suggesting their lives have been mapped for them by the legend attached to the ancestors; although, of course, this could simply be an example of a self-fulfilling prophecy. After telling the young Kitty and Eveline the story of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, he attempts to dismiss the suggestion that the family is cursed to re-enact the act of sororicide within the legend by declaring that ‘It’s nonsense. They’re just legends. There’s no truth in them’. However, the look of concern upon his face suggests he believes otherwise. For her part, this sense of fatalism seems to envelop Kitty. Commenting on her relationship with Martin, she observes bleakly that ‘Everything is changing. There’s a dark space in our lives and we’ll end up not understanding one another’. She adds shortly afterwards that ‘There’s something above us; a mysterious force that’s destroying us, and there’s nothing we can do to fight it’.  Much of the narrative is divided between the castle belonging to Tobias and the fashion house (Springe) where Kitty works as a photographer. (The focus on the fashion industry is a theme that crops up time and time again in examples of the thrilling all’italiana, from Sei donne per l’assassino onwards; as in many other films of the 1960s, the world of fashion seems to be used in these films as a symbol of the modern world.) Reflecting the division between these two spaces, the film’s narrative is part ghost story and part whodunit: the mysterious Red Queen, believed to be the ghost of Eveline, stalks the castle, but the most striking sequences see this spectre haunting the city beyond its walls, murdering Hans outside the park where he and Lulu are propositioning a prostitute for a threesome, and charging along the highly reflective surfaces of a long corridor in an ultra-modern Le Corbusier-style building. This scene, part of a nightmare experienced by Kitty, underscores the film’s juxtaposition of the past, represented by the Gothic castle and the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, and the present – with the anxieties within the narrative seeming to focus on the intrusion upon the latter by the former. Like Miraglia’s previous film, La dame rossa uccide sette volte narrativises a conflict between the supernatural and ‘real world’ explanations for mysterious events, and like the prior film it also features a journey into a psychiatric hospital – though whereas in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba, the film’s (male) protagonist Alan is released from psychiatric care, in La dama rossa uccide sette volte Martin’s wife is incarcerated in a mental hospital. Much of the narrative is divided between the castle belonging to Tobias and the fashion house (Springe) where Kitty works as a photographer. (The focus on the fashion industry is a theme that crops up time and time again in examples of the thrilling all’italiana, from Sei donne per l’assassino onwards; as in many other films of the 1960s, the world of fashion seems to be used in these films as a symbol of the modern world.) Reflecting the division between these two spaces, the film’s narrative is part ghost story and part whodunit: the mysterious Red Queen, believed to be the ghost of Eveline, stalks the castle, but the most striking sequences see this spectre haunting the city beyond its walls, murdering Hans outside the park where he and Lulu are propositioning a prostitute for a threesome, and charging along the highly reflective surfaces of a long corridor in an ultra-modern Le Corbusier-style building. This scene, part of a nightmare experienced by Kitty, underscores the film’s juxtaposition of the past, represented by the Gothic castle and the legend of the Red Queen and the Black Queen, and the present – with the anxieties within the narrative seeming to focus on the intrusion upon the latter by the former. Like Miraglia’s previous film, La dame rossa uccide sette volte narrativises a conflict between the supernatural and ‘real world’ explanations for mysterious events, and like the prior film it also features a journey into a psychiatric hospital – though whereas in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba, the film’s (male) protagonist Alan is released from psychiatric care, in La dama rossa uccide sette volte Martin’s wife is incarcerated in a mental hospital.

The Red Queen, Ian Olney has suggested, is ‘presented as an unstoppable force in the film – more superhero than villain’ (Olney, 2013: 122). She is ultimately ‘more interesting’ and ‘more sympathetic’ than ‘the nominal heroes in the film’: ‘the frigid, neurotic Kitty (who is, after all, a murderer herself) and her smarmy boyfriend, Martin’ (ibid.). The Red Queen’s victims either ‘richly deserve their fates’, such as the philandering Hans, or they ‘are onscreen so briefly that they barely have time to register with the audience’ (ibid.: 122-3) The fact that such characters are her victims makes the Red Queen ‘almost a righteous avenger in the film’, Olney argues (ibid.: 123). For Olney, the Red Queen is a femme fatale-like figure, and though ‘it can be tempting to dismiss the femme fatale as a negative reactionary stereotype’, quoting Janey Place’s work, Olney argues that femmes fatale within cinema are often remembered for their ‘strong, dangerous and, above all, exciting sexuality’ (ibid., quoting Janey Place). Olney adds that the fact that ‘most of her victims are connected in some way with an industry that objectifies women as a matter of commerce makes it possible to read her as a specter of feminist rage’ (ibid.). The film encourages us, via point-of-view shots from the Red Queen’s perspective as she spies on her victims, to ‘identify with her sadistic female gaze’; the use of point-of-view shots prompts the viewer to ‘identify with the female killer and to embrace the threat she represents to the patriarchal social order’ (ibid.). However, Olney’s reading of the film overlooks the fact that a significant number of examples of the thrilling all’italiana feature female killers: in fact, this was almost a paradigm of the thrilling all’italiana films of the period, beginning with Sei donne per l’assassino, consolidated in Argento’s debut feature and emulated in a number of Italian thrillers of the 1970s. The Red Queen, Ian Olney has suggested, is ‘presented as an unstoppable force in the film – more superhero than villain’ (Olney, 2013: 122). She is ultimately ‘more interesting’ and ‘more sympathetic’ than ‘the nominal heroes in the film’: ‘the frigid, neurotic Kitty (who is, after all, a murderer herself) and her smarmy boyfriend, Martin’ (ibid.). The Red Queen’s victims either ‘richly deserve their fates’, such as the philandering Hans, or they ‘are onscreen so briefly that they barely have time to register with the audience’ (ibid.: 122-3) The fact that such characters are her victims makes the Red Queen ‘almost a righteous avenger in the film’, Olney argues (ibid.: 123). For Olney, the Red Queen is a femme fatale-like figure, and though ‘it can be tempting to dismiss the femme fatale as a negative reactionary stereotype’, quoting Janey Place’s work, Olney argues that femmes fatale within cinema are often remembered for their ‘strong, dangerous and, above all, exciting sexuality’ (ibid., quoting Janey Place). Olney adds that the fact that ‘most of her victims are connected in some way with an industry that objectifies women as a matter of commerce makes it possible to read her as a specter of feminist rage’ (ibid.). The film encourages us, via point-of-view shots from the Red Queen’s perspective as she spies on her victims, to ‘identify with her sadistic female gaze’; the use of point-of-view shots prompts the viewer to ‘identify with the female killer and to embrace the threat she represents to the patriarchal social order’ (ibid.). However, Olney’s reading of the film overlooks the fact that a significant number of examples of the thrilling all’italiana feature female killers: in fact, this was almost a paradigm of the thrilling all’italiana films of the period, beginning with Sei donne per l’assassino, consolidated in Argento’s debut feature and emulated in a number of Italian thrillers of the 1970s.

In fact, Miraglia’s film seems to satirise the idea that the Red Queen may be perceived as a feminist avenger. Martin’s wife Elizabeth tells Martin that Eveline, who is presumed to be the Red Queen, visits her nightly: ‘She’s my friend. She comes to see me every night [….] Eveline tells me the truth. Eveline is good’. Incarcerated in the psychiatric hospital and seemingly harmless, Elizabeth appears to be a victim of a repressive patriarchal authority. She declares that ‘all men are filthy beasts, telling her husband ‘I hate you and I’m going to kill you, Martin’. Eveline/The Red Queen’s nightly visits to Elizabeth seem to be a declaration of sisterhood, reinforcing the idea put forward by Olney that the Red Queen is striking out against patriarchy and its institutions. However, a little later we are shown Elizabeth at night, conversing with the Red Queen who is on the other side of the fence that borders the psychiatric hospital. The Red Queen encourages Elizabeth to try to scale the fence, seeming to assist Martin’s wife in escaping from the repressive hospital. However, it’s a ploy: the Red Queen causes Elizabeth to fall, impaling her face on the metal railings and causing her death. In this sequence, the Red Queen seems to self-consciously present herself as the ‘feminist avenger’ that Olney claims her to be, only to reveal this to be a masquerade. By betraying Elizabeth’s trust, the Red Queen reveals her crusade to be deeply nihilistic - and this film, like its predecessor, seems to revel in the oh-so chic nihilism of the era in which it was made. In fact, Miraglia’s film seems to satirise the idea that the Red Queen may be perceived as a feminist avenger. Martin’s wife Elizabeth tells Martin that Eveline, who is presumed to be the Red Queen, visits her nightly: ‘She’s my friend. She comes to see me every night [….] Eveline tells me the truth. Eveline is good’. Incarcerated in the psychiatric hospital and seemingly harmless, Elizabeth appears to be a victim of a repressive patriarchal authority. She declares that ‘all men are filthy beasts, telling her husband ‘I hate you and I’m going to kill you, Martin’. Eveline/The Red Queen’s nightly visits to Elizabeth seem to be a declaration of sisterhood, reinforcing the idea put forward by Olney that the Red Queen is striking out against patriarchy and its institutions. However, a little later we are shown Elizabeth at night, conversing with the Red Queen who is on the other side of the fence that borders the psychiatric hospital. The Red Queen encourages Elizabeth to try to scale the fence, seeming to assist Martin’s wife in escaping from the repressive hospital. However, it’s a ploy: the Red Queen causes Elizabeth to fall, impaling her face on the metal railings and causing her death. In this sequence, the Red Queen seems to self-consciously present herself as the ‘feminist avenger’ that Olney claims her to be, only to reveal this to be a masquerade. By betraying Elizabeth’s trust, the Red Queen reveals her crusade to be deeply nihilistic - and this film, like its predecessor, seems to revel in the oh-so chic nihilism of the era in which it was made.

Video

Both pictures are uncut. La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba has a running time of 102:48, whilst La dama rossa uccide sette volte runs for 99:15 mins. Both pictures are uncut. La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba has a running time of 102:48, whilst La dama rossa uccide sette volte runs for 99:15 mins.

Both films take up approximately 27Gb of space on their respective Blu-ray discs. The 1080p presentations use the AVC codec and are in the films’ original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba was shot in Techniscope, whilst La dama rossa uccide sette volte was filmed in Cromoscope. These two processes were for all intents and purposes the same; the difference was that they were handled at different laboratories. (Arrow’s recent release of Sergio Martino’s La morte accarezza a mezzanotte and La morte cammina con i tacchi alti likewise features two films made by the same director, and usually grouped together, shot in Cromoscope and Techniscope, respectively.) Both Techniscope and Cromoscope were 2-perf widescreen processes that used spherical, rather than anamorphic, lenses. They were cost-saving in the sense that, by halving the size of each frame in comparison with anamorphic (4-perf) widescreen processes, they reduced the negative costs involved in making a film by half. However, this was reputedly offset to some extent by lab costs, which it’s said were more expensive for films shot in 2-perf formats like Techniscope/Cromoscope; it’s been suggested that increases in lab costs were one of the reasons why 2-perf non-anamorphic widescreen processes such as these became less popular during the late 1970s and the 1980s.  Release prints of Techniscope/Cromoscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.) Release prints of Techniscope/Cromoscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)

Both films in this set are presented in new 2k scans of the original negatives, thus bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage. Owing to the fact that the sources of both presentations were the films’ original negatives, blacks are deep and rich, more in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of both films is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the vintage prints of Techniscope films made after around 1970. Both films in this set are presented in new 2k scans of the original negatives, thus bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage. Owing to the fact that the sources of both presentations were the films’ original negatives, blacks are deep and rich, more in line with Techniscope pictures processed using the dye transfer process than the later Techniscope pictures which were processed using the Kodak colour printing process (and which involved the production of a dupe negative that, as noted above, weakened contrast and produced a coarser grain structure). Likewise, the grain structure of both films is natural and organic and, owing to the source being a new transfer of the negative (bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage), without the coarseness that characterised some of the vintage prints of Techniscope films made after around 1970.

Both of the films in this set feature the characteristics of Techniscope/Cromoscope pictures. There’s heavy use of short focal lengths, and the majority of shots are staged in depth (including the nightmarish scene in which the Red Queen runs along the corridor of a very modern building, the rapid movement from background to the foreground of the frame deeply unsettling). This depth within the photography is communicated very well in the presentations of both films. Contrast levels are very good, with a strong and effective balance of light and dark accompanied by defined mid-tones. (There are some day-for-night shots in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba that don’t fare as well as the rest of the film in this regard, but this would seem to be owing to the characteristics of the original photography within these scenes.) Blacks are deep and inky too, as noted above. A very good level of detail is present, though some shots look a little soft and diffused. Both presentations are very ‘clean’ and free from damage and debris. The colour palette of the presentations of both films seems natural and ‘healthy’ though with a different hue in some scenes to the presentations of both films on NoShame’s DVD releases. Both presentations certainly offer a big upgrade over the films’ previous DVD releases, including the box set from NoShame Films in the US. As each disc begins, the viewer is presented with the choice of watching the film with either English or Italian onscreen text. The latter is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the onscreen text, which are turned on by default. La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba

La dama rossa uccide sette volte

NB. Some larger screen grabs from both films are included below, along with a visual comparison of Arrow’s presentations of both pictures with NoShame Films’ DVD releases.

Audio

With both films, the viewer is presented with a choice of a lossless Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 track or an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 track. In the case of both pictures, the former is accompanied by optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue, whilst the latter is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. With both films, the viewer is presented with a choice of a lossless Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 track or an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 track. In the case of both pictures, the former is accompanied by optional English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue, whilst the latter is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba is one of those curious examples of the thrilling all’italiana that is set in England, and consequently in the English dub the voice actors adopt a variety of English accents, some more convincing than others. Nevertheless, in the case of both films the English dubs are pretty good: there are some noticeable differences between the Italian dialogue and the English dubbed dialogue in both films, but these differences aren’t earth-shattering. Certainly, if your preference is to watch such films in their English dubbed variant, you’ll be happy with what’s on offer here; and likewise, the Italian audio tracks for both films are equally pleasing and a little more satisfying, in terms of their audio qualities, than the English tracks. In the case of La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba, the English language track sounds a little more clipped than the Italian track and also has an element of warble to it that’s not present in the Italian track; whereas in the case of La dama rossa uccide sette volte, the English track feels a little muted in comparison with the Italian track. Both films feature excellent scores by Bruno Nicolai, which are presented particularly well on the Italian tracks for both pictures. (The score for La dama rossa uccide sette volte contains a motif that is repeated in Nicolai’s score for Jess Franco’s La nuit des étoiles filantes/A Virgin Among the Living Dead, 1973.)

Extras

DISC ONE:  La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba (102:48) La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba (102:48)

- Audio commentary with critic Troy Howarth. This is an excellent commentary in which Troy enthusiastically engages with the film, exploring its themes and discussing its relationship with other examples of the thrilling all’italiana. - Optional introduction by Erika Blanc (0:54). Blanc introduces the film, saying ‘I’ve always loved this film’. - ‘Remembering Evelyn’ (15:12). Here, in a newly-filmed piece, critic Stephen Thrower reflects on La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. Thrower talks about the film’s origins and its original shooting title. He discusses the film as ‘a murder thriller that’s pulling in a lot of Gothic elements’, which ‘add a great deal of extra colour to the story’. Thrower talks about some of the symbolism within the film, especially in terms of its juxtaposition of the Gothic and the modern. - ‘The Night Erika Came Out of the Grave’ (9:44). In a new interview, Erika Blanc discusses her performance in La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. She reflects on her role as the nightclub dancer Susan. She talks about acting with Anthony Steffen, who she regarded as ‘a dear friend’. She suggests that he ‘was such a vain man’ and would look into a compact mirror before each take, perfecting his ‘pout’ prior to the cameras rolling. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - Trailers: Italian trailer (2:44); English trailer (2:44). The following have been carried over to this release from the film’s DVD release by NoShame Films: - 2006 Introduction by Erika Blanc (0:37). Here, Blanc advises the viewer not to watch the film alone ‘because it’s very scary’. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Whip and the Body’ (20:57). Blanc discusses her performance in the film. There’s much overlap with the newer interview with Blanc that’s included on this disc. Again, this is in Italian with optional English subtitles. - ‘Still Rising from the Grave’ (22:48). Production designer Lorenzo Baraldi talks about his work on the film. He also talks about his broader career working for some of the most significant filmmakers of the era. He reflects on the diversity within Italian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s: ‘it was like a big cake, with many different layers’, he says. Baraldi speaks in Italian, accompanied by optional English subtitles. DISC TWO:  La dama rossa uccide sette volta (99:15) La dama rossa uccide sette volta (99:15)

- Audio commentary with Alan Jones and Kim Newman. Jones and Newman provide a lively commentary track in which they discuss the film’s melange of elements of the Gothic horror film and giallo all’italiana. They discuss the cast within the film and joke about the difficulties in keeping track of who kills whom. - Optional introduction by production designer Lorenzo Baraldi (0:38). Baraldi introduces the film, in Italian (with optional English subtitles), by highlighting the care that went into its production. - ‘The Red Reign’ (13:48). In this newly-filmed piece, Stephen Thrower discusses the film, highlighting its marriage ‘of Gothic elements and giallo elements’. He suggests that the film’s plotting ‘throw[s] curveballs all the time’, constantly putting the viewer ‘on the back foot’; but queries whether or not this was intentional. Thrower also talks about the similarities between this film and Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973).  - ‘Life of Lulu’ (19:47). In a new interview, Sybil Danning talks about her role in the film. She discusses her early life prior to becoming an actress and the events that led to her becoming a model and then progressing into the world of acting. - ‘Life of Lulu’ (19:47). In a new interview, Sybil Danning talks about her role in the film. She discusses her early life prior to becoming an actress and the events that led to her becoming a model and then progressing into the world of acting.

- Alternative Opening (0:39). This is a different version of the film’s opening. - Trailers: Italian trailer (3:13); English trailer (3:13). The following have been carried over to this release from the film’s DVD release by NoShame Films: - ‘Dead a Porter’ (13:38). Lorenzo Baraldi, the film’s production designer, talks about the fact that the film was made owing to the success of La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba. He talks about the shooting locations and the sets he created for the film. This is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Round Up the Usual Suspects!’ (18:24). Marino Mase discusses his work on the film and also talks about his co-stars. He reflects on the shooting of the film in Germany and the level of organisation involved in the production. Again, this is in Italian with optional English subtitles. - ‘If I Met Emilio Miraglia Today…’ (4:14). Mase, Erika Blanc and Baraldi discuss how they would react if they met Miraglia again, thirty years after the making of La dama rossa uccide sette volte. - ‘My Favourite… Films’ (0:59). Barbara Bouchet discusses her experiences at a film festival and her surprise at how positively American fans responded towards La dama rossa uccide sette volte, Lucio Fulci’s Non se sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972) and Paolo Cavara’s La tarantola dal ventre nero (Black Belly of the Tarantula, 1971) – the trio of thrilling all’italiana films in which Bouchet starred during the early 1970s. Bouchet speaks in Italian, with optional English subtitles. Retail copies come with a 60 page booklet containing a variety of new articles about the films.

Overall

Arrow’s new boxed set contains two very good examples of the thrilling all’italiana. The combination of elements of the thriller with some of the iconography of Gothic horror cinema ensures that these films remain interesting. The films are beautifully shot, with some excellent set design. Arrow’s presentation of both films is very good, and the inclusion of both Italian and English versions of the films is welcome too. The new HD presentations are a clear improvement over the films’ previous DVD releases (though fans will probably want to hang on to the NoShame DVD boxed set containing both films owing to the inclusion of the Red Queen figurine). Both films are also accompanied here by some excellent contextual material, including all of the material from the NoShame DVD releases alongside some superb new special features. The two commentary tracks are very good indeed, and the interviews with Stephen Thrower offer some strong critical insight into the films. For fans of the thrilling all’italiana, this release is surely a must-buy. Arrow’s new boxed set contains two very good examples of the thrilling all’italiana. The combination of elements of the thriller with some of the iconography of Gothic horror cinema ensures that these films remain interesting. The films are beautifully shot, with some excellent set design. Arrow’s presentation of both films is very good, and the inclusion of both Italian and English versions of the films is welcome too. The new HD presentations are a clear improvement over the films’ previous DVD releases (though fans will probably want to hang on to the NoShame DVD boxed set containing both films owing to the inclusion of the Red Queen figurine). Both films are also accompanied here by some excellent contextual material, including all of the material from the NoShame DVD releases alongside some superb new special features. The two commentary tracks are very good indeed, and the interviews with Stephen Thrower offer some strong critical insight into the films. For fans of the thrilling all’italiana, this release is surely a must-buy.

References: Bondanella, Peter, 2009: A History of Italian Cinema. London: Continuum International Publishing Dyer, Richard, 2015: Lethal Repetition: Serial Killing in European Cinema. London: Palgrave Macmillan Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Met, Philippe, 2006: ‘“Knowing Too Much” About Hitchcock: The Genesis of the Italian Giallo’. In: Boyd, David & Palmer, R Barton (eds), 2006: After Hitchcock: Influence, Imitation, and Intertextuality. University of Texas Press: 195-214 Olney, Ian, 2013: Euro Horror: Classic European Cinema in Contemporary American Culture. Indiana University Press Visual Comparison with NoShame’s DVD releases: La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

La dama rossa uccide sette volte NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

NoShame DVD:

Arrow BD:

La notte che Evelyn uscì dalla tomba

La dama rossa uccide sette volte

|

|||||

|