|

The Film

Woman on the Run (Norman Foster, 1950) Woman on the Run (Norman Foster, 1950)

Based on a story (‘Man on the Run’) by Sylvia Tate that was published in American Magazine in April, 1948, Norman Foster’s Woman on the Run (1950) features a plot which, arguably, uses a crime – a murder depicted in the film’s opening moments – as a pretext for the examination of a marriage in decline. In some ways, the film may be compared to Roman Polanski’s much later Frantic (1988), which likewise features an espionage plot in which two spouses are separated, with Dr Richard Walker (Harrison Ford) desperately seeking his wife Sondra (Betty Buckley): in Polanski’s film, much as in Woman on the Run, the spy plot essentially serves as a catalyst for the film’s major area of focus, an examination of a marriage.

The film begins in San Francisco, with an Irish man, Joe Gordon (Thomas P Dillon), being murdered in a gangland hit by an assassin, ‘Danny Boy’, who is working on the orders of known gangster Smiley Freeman. Gordon’s murder is witnessed by Frank Johnson (Ross Elliott). Frank can identify the killer but wants no part in the investigation, fearing reprisals. Investigating the murder of Gordon, Inspector Ferris (Robert Keith) questions Frank. However, Frank disappears. Ferris turns his sights on Frank’s wife Eleanor (Ann Sheridan), only to discover that the Johnsons have a very strange marriage: Eleanor shows apparently no concern for her missing husband. However, Ferris’ revelation that Frank has a heart condition of which Eleanor is unaware piques Eleanor’s interest.

Aware that Frank may suffer a fatal heart attack unless he receives the correct medication, Eleanor attempts to track her husband down. Along the way, she enlists the help of reported Dan Legget (Dennis O’Keefe). Working with O’Keefe, Eleanor scours San Francisco for Frank, speaking with the people who knew him. Her opinion of her husband begins to change: for example, she realises that he is highly regarded by his colleague Maibus (John Qualen), for whom Frank put his job on the line. Her sexless opinion of Frank is also challenged by an office girl in Frank’s office, who verbalises her crush on Frank, though as Maibus suggests Frank is utterly devoted to his wife – no matter how severe her attitude towards him may be. However, as Eleanor warms to her absent husband, she comes to the realisation that her attempts to track him down may inadvertently be leading Gordon’s killer to the only witness to the murder. Aware that Frank may suffer a fatal heart attack unless he receives the correct medication, Eleanor attempts to track her husband down. Along the way, she enlists the help of reported Dan Legget (Dennis O’Keefe). Working with O’Keefe, Eleanor scours San Francisco for Frank, speaking with the people who knew him. Her opinion of her husband begins to change: for example, she realises that he is highly regarded by his colleague Maibus (John Qualen), for whom Frank put his job on the line. Her sexless opinion of Frank is also challenged by an office girl in Frank’s office, who verbalises her crush on Frank, though as Maibus suggests Frank is utterly devoted to his wife – no matter how severe her attitude towards him may be. However, as Eleanor warms to her absent husband, she comes to the realisation that her attempts to track him down may inadvertently be leading Gordon’s killer to the only witness to the murder.

The film contains some wonderful hard-boiled dialogue. In the opening sequence, prior to his murder by ‘Danny Boy’, Joe Gordon tells his killer that ‘I’m giving it to you without the hoopla, Danny Boy. The simple facts of life. I’m sitting in the middle with the cops on one side, Smiley Freeman on the other and the both of them gunning for me. So I’m the guy that knows you’re the one who took the twenty grand from Smiley to cover up the dirk and kill him’. The overkill in the opening murder of Gordon is shocking: the victim is shot several times at point blank range, all the while pleading for his life. It’s a brutal scene that, although the film was made sixty-five years ago, is still shocking today. Given the brutality of the murder, Frank’s reticence to come forward as a witness is understandable; this is compounded when he’s mocked by the police themselves. ‘I hate to get mixed up on this’, Frank tells Ferris. Hearing this, a uniformed police officer declares sarcastically, ‘Yeah, it’s getting so a man has to be careful which way he’s looking these days’.

Woman on the Run is part of a distinct group of examples of film noir that include a female detective: other films in this trend include Phantom Lady (Robert Siodmak, 1944), in which secretary Ella Raines (Carol Richman) works to prove the innocence of her employer; and the Cornell Woolrich adaptation Black Angel (Roy William Neill, 1946), which features a woman, Catherine (June Vincent), investigating to prove the innocence of her husband. Philippa Gates suggests that though these films tapped into the zeitgeist of the era, a period in which traditional gender roles were being renegotiated owing to the cultural fallout of the Second World War, their focus on female detective protagonists was ‘surprising’ in the context of the paradigms of film noir, in which ‘independent women tended to be branded as the dangerous femme fatale’ (Gates, 2010: 248). The majority of these films, as Gates observes, feature a female investigator who is driven ‘to save the man she loves’ and thus prove herself ‘to be a dutiful wife rather than an independent career woman’ (ibid.). Woman on the Run is part of a distinct group of examples of film noir that include a female detective: other films in this trend include Phantom Lady (Robert Siodmak, 1944), in which secretary Ella Raines (Carol Richman) works to prove the innocence of her employer; and the Cornell Woolrich adaptation Black Angel (Roy William Neill, 1946), which features a woman, Catherine (June Vincent), investigating to prove the innocence of her husband. Philippa Gates suggests that though these films tapped into the zeitgeist of the era, a period in which traditional gender roles were being renegotiated owing to the cultural fallout of the Second World War, their focus on female detective protagonists was ‘surprising’ in the context of the paradigms of film noir, in which ‘independent women tended to be branded as the dangerous femme fatale’ (Gates, 2010: 248). The majority of these films, as Gates observes, feature a female investigator who is driven ‘to save the man she loves’ and thus prove herself ‘to be a dutiful wife rather than an independent career woman’ (ibid.).

Certainly, in Woman on the Run Eleanor’s motive towards the end of the film is to save Frank from ‘Danny Boy’: to track down her husband and warn him to come in from the proverbial cold, seeking the protection of the police. However, in the film’s early sequences Eleanor is still presented as a femme fatale of sorts: cold and unsympathetic towards her husband, though she doesn’t instigate the antagonist’s plot to hunt down and kill Frank, she displays an indifference towards her husband’s fate until, as the narrative progresses, her attitude towards Frank begins to soften when she encounters various characters who can do nothing but sing his praises and, essentially, make Eleanor realise how dutiful and devoted Frank is towards their marriage. ‘Just like him’, Eleanor says in reference to her husband when he flees from the police questioning at the start of the film, ‘Always running away’. ‘Running away from what?’, Ferris asks. ‘From everything’, Eleanor responds. In fact, the dialogue acknowledges the fact that Frank’s flight seems as much from his marriage to Eleanor as from the fear that ‘Danny Boy’ might seek to eliminate him as a witness in the murder of Joe Gordon. ‘I don’t think he’s running away from us’, Ferris tells Eleanor at one point, ‘He’s running away from you’. This observation comes not long after Ferris has told Eleanor that ‘You didn’t do your husband any favours [….] It’s bad enough to be alone in the big city without anywhere to go, but as son as the papers hit the streets and the killer finds out he didn’t get your husband, there’ll be guys looking for him with guns’. Ferris finishes his monologue by suggesting that by enabling her husband to escape from the police, Eleanor has – perhaps subconsciously – wittingly sealed his death warrant: ‘If I had a husband I wanted to get rid of, I’d do exactly what you did’, Ferris says, adding in reference to Eleanor’s apparent callousness towards Frank, ‘No wonder the world is full of bachelors’.

Elsewhere, Philippa Gates has observed, ‘in Woman on the Run, the mystery that Eleanor Johnson […] must solve is not the murder that her husband witnessed but rather who killed their marriage’ (Gates, 2014: 29). Gates suggests that that the picture ‘identifies Eleanor as the culprit’ (ibid.): as the narrative progresses, she realises the warmth with which Frank’s colleagues and friends regard him and acknowledges that her treatment of him has been too severe. Gates argues that the film suggests ‘she must submit to male authority—her husband and the film—by the end of the film’ (ibid.). This moment comes when, after speaking with Maibus and realising how dedicated Frank is to his job and how devoted he is to Eleanor that the mannequins he makes bear her face, Eleanor observes to Legget that she has realised something: ‘Something I hadn’t counted on [….] Frank still loves me’. Elsewhere, Philippa Gates has observed, ‘in Woman on the Run, the mystery that Eleanor Johnson […] must solve is not the murder that her husband witnessed but rather who killed their marriage’ (Gates, 2014: 29). Gates suggests that that the picture ‘identifies Eleanor as the culprit’ (ibid.): as the narrative progresses, she realises the warmth with which Frank’s colleagues and friends regard him and acknowledges that her treatment of him has been too severe. Gates argues that the film suggests ‘she must submit to male authority—her husband and the film—by the end of the film’ (ibid.). This moment comes when, after speaking with Maibus and realising how dedicated Frank is to his job and how devoted he is to Eleanor that the mannequins he makes bear her face, Eleanor observes to Legget that she has realised something: ‘Something I hadn’t counted on [….] Frank still loves me’.

As the film begins, Eleanor displays indifference towards Frank: the detective investigating the murder remarks on how sparsely furnished Eleanor and Frank’s home is, the kitchen cupboards stocked with cans of dog food: the dog acts as a surrogate child, holding together this frayed marriage. ‘The dog is our only mutual friend’, Eleanor tells Ferris. ‘You always go to sleep while he walks the dog?’, Ferris asks her. ‘No. Sometimes he goes to sleep while I walk the dog’, she responds. The sterility of Eleanor and Frank’s home is a metaphor for their marriage. Eleanor blames Frank’s lack of ambition – his willingness to submit to a job designing mannequins rather than aspiring to become a great artist – for the ‘failure’ of their marriage. ‘It takes more than talent to have a career’, Eleanor observes in the presence of Ferris and referring to her husband’s ‘failure’ as an artist, ‘You have to have staying power. Frank’s a drifter, so when money ran out, he just drifted’. On the other hand, as the film progresses the filmmakers shift the blame onto Eleanor, suggesting that she has been unwilling to see her husband’s positive attributes, and that his perceive lack of ambition is not necessarily the flaw in his character that Eleanor has to that point believed it to be. In the mannequins Frank has designed, Eleanor recognises herself: the early mannequins are idealised and display a contented countenance; the later models have a harshness to their expression and a severity that, Eleanor concludes, Frank sees in his wife. Meanwhile, his colleague sings Frank’s praises, and in reference to Frank one of the women who works for the company observes, unaware that Eleanor is Frank’s wife, ‘Boy, have I got a crush on that man?’ Her comment makes Eleanor aware that Frank is an object of desire for other women.

In some ways, the structure of the film’s narrative might be compared to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) or Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). Though, unlike those films, Woman on the Run doesn’t feature a flashback structure, like Citizen Kane and The Killers the film begins with the absence of an enigmatic character – in this case, Frank. Unlike Charles Foster Kane, Frank is of course not dead; but by fleeing from the police, his wife and Smiley Freeman’s thugs, Frank makes himself absent in a different kind of way. His disappearance causes his wife Eleanor to investigate his life, speaking with the people who knew him, including his colleagues, and unwrapping the enigma that is her husband’s life – or perhaps, the enigma of love itself. Sitting in a cab with Legget, towards the end of the film Eleanor observes reflectively, ‘What was I holding out for? Why didn’t I learn to understand him? Why don’t we give freely of ourselves when we can?’ Later, when she and Legget arrive at Playland on the Beach (the setting for the film’s climax), Legget tells Eleanor, ‘I used to come here with a girl when I was a lad’. ‘It’s more frightening than romantic’, Eleanor observes in relation to the carnivalesque atmosphere, the loud noises from the machinery and the raucous laughter of the visitors. ‘That’s the way love is when you’re young; how life is when you’re older’. In some ways, the structure of the film’s narrative might be compared to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) or Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946). Though, unlike those films, Woman on the Run doesn’t feature a flashback structure, like Citizen Kane and The Killers the film begins with the absence of an enigmatic character – in this case, Frank. Unlike Charles Foster Kane, Frank is of course not dead; but by fleeing from the police, his wife and Smiley Freeman’s thugs, Frank makes himself absent in a different kind of way. His disappearance causes his wife Eleanor to investigate his life, speaking with the people who knew him, including his colleagues, and unwrapping the enigma that is her husband’s life – or perhaps, the enigma of love itself. Sitting in a cab with Legget, towards the end of the film Eleanor observes reflectively, ‘What was I holding out for? Why didn’t I learn to understand him? Why don’t we give freely of ourselves when we can?’ Later, when she and Legget arrive at Playland on the Beach (the setting for the film’s climax), Legget tells Eleanor, ‘I used to come here with a girl when I was a lad’. ‘It’s more frightening than romantic’, Eleanor observes in relation to the carnivalesque atmosphere, the loud noises from the machinery and the raucous laughter of the visitors. ‘That’s the way love is when you’re young; how life is when you’re older’.

The film benefits from some excellent location shooting in San Francisco, evidenced in some of the montages in which Eleanor and Legget search for Frank at various locations. The finale, in which Eleanor rides a rollercoaster whilst Danny Boy closes in on Frank, was shot at Carmel’s Playland on the Beach, which was torn down in 1972. The sound of Playland on the Beach’s famous Laughing Sal doll punctuates the climax, as Eleanor is thrown about by the rollercoaster, seemingly helpless to prevent the murder of Frank, which is taking place below her. The opening sequence was shot on the Hill Street terrace, which sits above the southern entrance to the Hill Street tunnel, a location that features in a number of films of the period, including Robert Wise’s The Set-Up (1949). Alongside this superb location work and the snappy hardboiled dialogue mentioned above, there are some dryly funny scenes too. Visiting a bar in the search for Frank, Eleanor encounters a drunken woman, a blowsy blonde. Realising Eleanor is looking for her husband, this woman slurs, ‘No use looking, honey. Once they’re gone, they’re gone’. A scene in which Eleanor feeds the couple’s dog Rembrandt a meal laced with Tabasco sauce, so that she may make him sick and thus justify a visit to the vet away from the eyes of the police who are watching her, seems to be intended to be funny but may make animal lovers wince a little.

The film was the subject of a plagiarism suit: though apparently based on the aforementioned story ‘Man on the Run’ by Sylvia Tate, two writers – Manuel Seff and Paul Yawitz – claimed that the film’s narrative bore strong similarities to a story they had written called ‘Pay the Piper’. The case was settled out of court.

Video

Taking up 18Gb of space on the disc, this presentation of Woman on the Run is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 78:06 mins. Taking up 18Gb of space on the disc, this presentation of Woman on the Run is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 78:06 mins.

The booklet contains details of the restoration on which this presentation is based. This restoration was conducted by UCLA in conjunction with the Film Noir Foundation. The restoration was based on a 35mm dupe negative, which as the detailed notes in the booklet accompanying this release tells us was the only surviving pre-print element. From this, the UCLA struck an answer print, then a release print, and finally a fine grain master from which the 2k scan used for this presentation was taken.

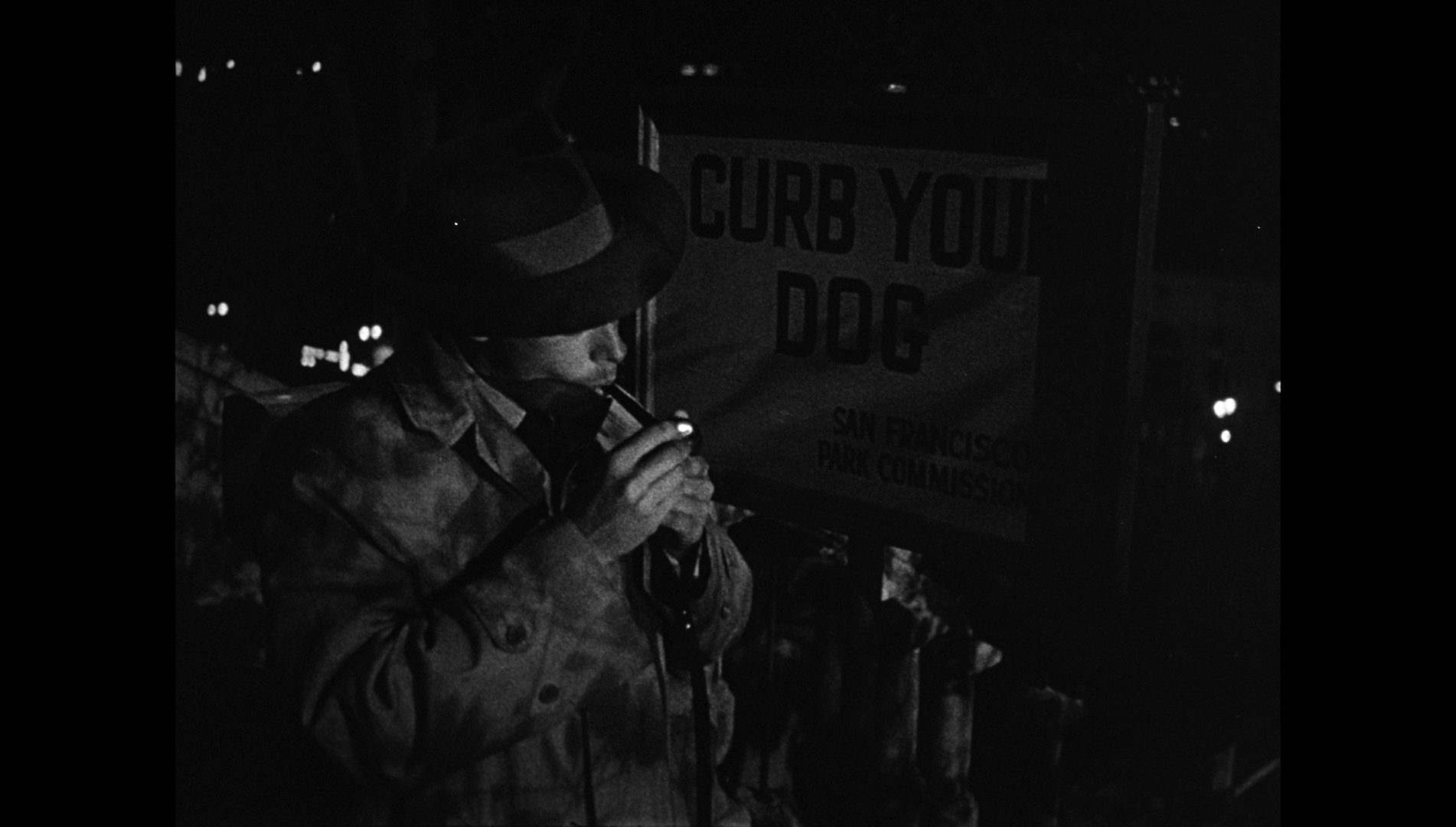

The source for the restoration exhibits some damage, with white flecks and specks indicating marks on the (dupe) negative. These are present throughout though they’re not heavy and certainly not too distracting. There are also some scratches present here and there. The damage here is wholly organic and related to the film source, like watching a vintage print. There’s a good level of detail present throughout the film. Some of the nighttime footage shot on location (eg, the opening sequence) looks a little underexposed, which is most likely owing to shooting under (predominantly) available light within the restrictions of the speed of the film stocks used during the production, whilst maintaining a strong depth of field; and therefore is a characteristic of the film’s photography. (Certainly, the scenes clearly shot in a studio – such as the interiors and the various cab rides that Legget and Eleanor undergo – aren’t underexposed in such a way.) This arguably makes these sequences more effective, and is a characteristic of other films noir shot on location at night during this era. Contrast is bold but good, with defined midtones and detail in the highlights balanced by the rich, deep shadows we associate with the photography within films noir. The film has the natural grain structure of 35mm film, which is carried well within a robust encode to disc. In sum, it’s an organic, if slightly ‘worn’, presentation.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. The information in the booklet tells us that in the absence of a good film source for this track, the audio was lifted from a videotaped recording that Eddie Muller made of a 35mm vault print held by Universal – which subsequently was lost in the well-documented 2008 fire which destroyed a large number of Universal’s archival prints. Given its source, the track is good: it’s clear with relatively good range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included too.

Extras

The disc includes:

- an audio commentary by film noir historian Eddie Muller. In this carefully-scripted and research commentary track, Muller reflects on the origins of the film and how it came to be made. He talks about its role within Sheridan’s career and how it was received. He offers critical discussion of the film’s themes too. It’s an excellent track that any fan of classic films noir will find to be a joy. - an audio commentary by film noir historian Eddie Muller. In this carefully-scripted and research commentary track, Muller reflects on the origins of the film and how it came to be made. He talks about its role within Sheridan’s career and how it was received. He offers critical discussion of the film’s themes too. It’s an excellent track that any fan of classic films noir will find to be a joy.

- ‘Love is a Rollercoaster: Woman on the Run Revisited’ (16:50). Made by the Film Noir Foundation, this featurette explores the making of the film and includes interviews with a number of film historians. It features Eddie Muller reflecting on Ann Sheridan’s role in producing the film. Kim Morgan suggests that the film ‘is a really interesting take on marriage. It’s a very modern look at marriage’, and Alan K Rode discusses Norman Foster’s role as director – ‘a protégé of Orson Welles and a great stylist in his own right’. Julie Kirgo says the film is ‘an atypical film noir’ in that it’s ‘strangely more about a relationship that we never actually see in operation [and] which becomes the focus of the film’. Muller suggests that the film’s depiction of the Johnson’s marriage may perhaps have been informed by Alan Campbell’s marriage to Dorothy Parker. Kirgo argues that the film represents a state in post-war American society where, following a separation during the war, married couples had to look afresh at their relationships with their spouses.

- ‘Restoring Woman on the Run’ (5:08). In another piece by the Film Noir Foundation, the history of the film’s restoration is discussed by Muller, Rode and film preservationist Scott MacQueen.

- ‘Locations: Then and Now’ (6:59). This featurette, as the title suggests, focuses on a comparison of the locations used in the film (represented through clips from the film itself) with how those locations appear now (represented through still photographs).

- ‘Noir City’ (9:51). Focusing on the annual Noir City Film Festival that takes place in San Francisco, this piece begins with a young man watching a film noir on his mobile telephone before picking up a promo card for the Noir City Film Festival, then segues into the same young man enjoying his time at the festival itself before presenting us with a montage of images from one of the events. This leads into an interview with Eddie Muller, billed onscreen as the ‘Czar of Noir’, talking about the festival. Comments from various attendees of the festival are also presented. One interviewee suggests that the ‘one great theme’ of film noir is simply that ‘You’re fucked’.

- Stills gallery (0:34).

Retail copies include a gorgeous booklet illustrated with delicious monochrome stills from the film and a great article by Eddie Muller about the restoration of the film.

Overall

Woman on the Run is a very good film. As noted above, it uses its crime plot as a pretext to examine the marriage of Frank and Eleanor. Legget’s line about love ‘when you’re younger’ being ‘more frightening than romantic’ and his suggestion that this is ‘how life is when you’re older’ anchors the film’s mature approach to love and relationships. The film’s use of a playground that becomes the site of a nightmarish scenario echoes the funhouse climax of Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1947) and predates Herk Harvey’s use of Saltair Pavilion in his 1962 horror film Carnival of Souls. Beautifully photographed and acted to perfection (with some great, snappy exchanges between Sheridan and O’Keefe, in particular), it’s an eminently watchable film noir. The presentation on this disc is, given the manner in which it was assembled, very good, and it is accompanied by some superb contextual material. Fans of films noir will find this to be an essential purchase, alongside Arrow’s release of Byron Haskin’s Too Late for Tears (1949), which is due out on the same day. Woman on the Run is a very good film. As noted above, it uses its crime plot as a pretext to examine the marriage of Frank and Eleanor. Legget’s line about love ‘when you’re younger’ being ‘more frightening than romantic’ and his suggestion that this is ‘how life is when you’re older’ anchors the film’s mature approach to love and relationships. The film’s use of a playground that becomes the site of a nightmarish scenario echoes the funhouse climax of Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1947) and predates Herk Harvey’s use of Saltair Pavilion in his 1962 horror film Carnival of Souls. Beautifully photographed and acted to perfection (with some great, snappy exchanges between Sheridan and O’Keefe, in particular), it’s an eminently watchable film noir. The presentation on this disc is, given the manner in which it was assembled, very good, and it is accompanied by some superb contextual material. Fans of films noir will find this to be an essential purchase, alongside Arrow’s release of Byron Haskin’s Too Late for Tears (1949), which is due out on the same day.

References

Gates, Philippa, 2010: ‘Criminal Investigation on Film’. In: Rzepka, Charles & Horsley, Lee (eds), 2010: A Companion to Crime Fiction. London: Wiley-Blackwell: 344-55

Gates, Philippa, 2014: ‘The Vanishing Love Song of Film Noir’. In: Miklitsch, Robert (ed), 2014: Kiss the Blood Off My Hands: On Film Noir. University of Illinois Press: 17-36

|