|

The Film

Dead End Drive-In (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1986) Dead End Drive-In (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1986)

Based on Peter Carey’s 1972 short story ‘Crabs’, Brian Trenchard-Smith’s Dead End Drive-In (1986) envisages a ‘future’ (at the time the film was made) society which is on the brink of economic collapse. Taking place in 1990, the film’s narrative focuses on Jimmy Rossini, aka ‘Crabs’ (Ned Manning). The puny Crabs lives with his mother and much stronger brother Frank (Ollie Hall), who runs a business salvaging materials from fatal car crashes. However, at the sites of these crashes Frank must contend with the Karboys,roving gangs of youths in jerry-rigged vehicles who employ violence in their attempts to steal from wrecked vehicles.

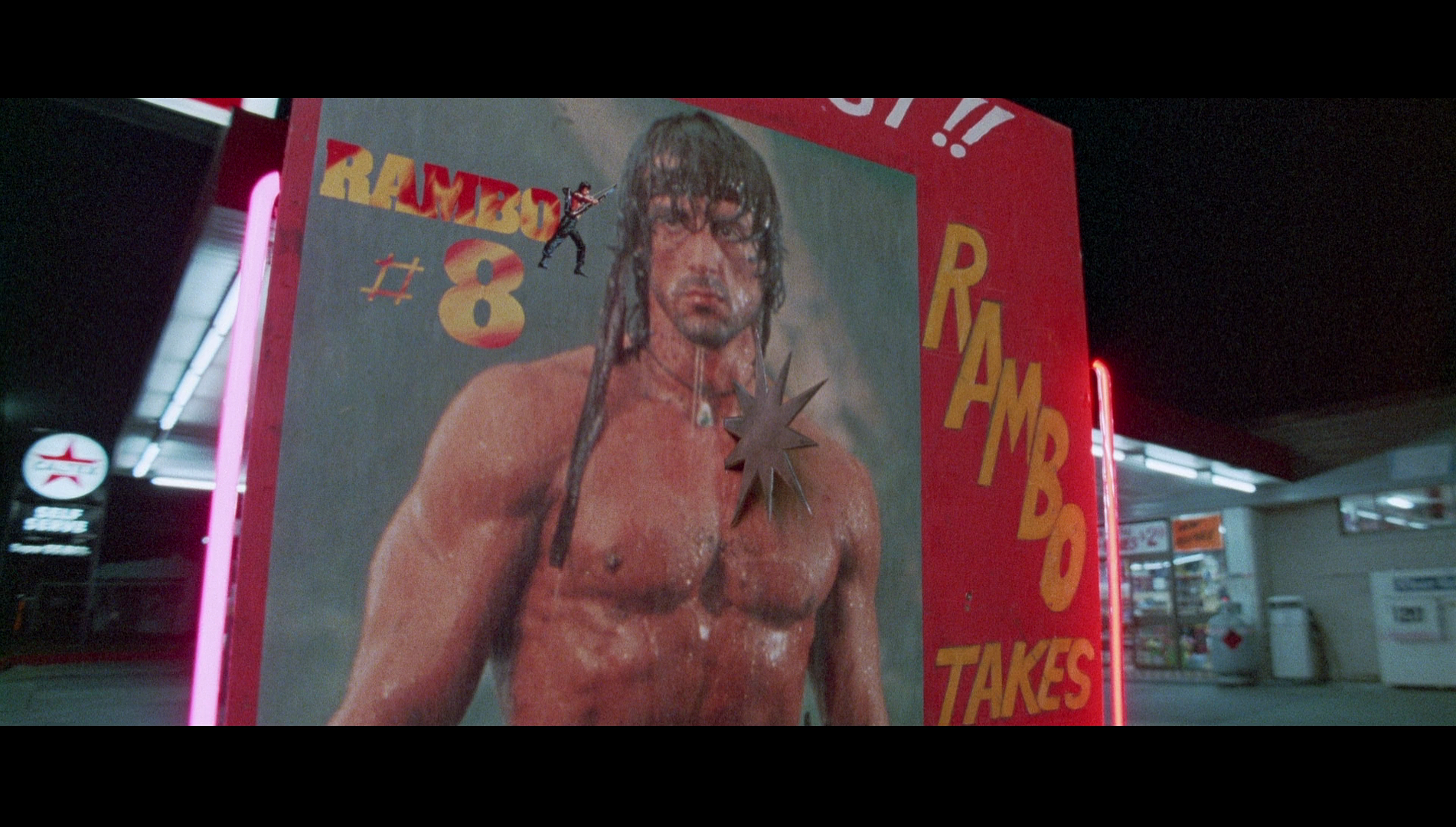

Frank has two vehicles, both of them painted a vibrant cherry red: a tow truck and a ’57 Chevy. Crabs makes a deal with his brother Frank, who agrees to let Crabs borrow the Chevy in order for Crabs to take his girlfriend Carmen (Natalie McCurry) out on a date. Crabs takes Carmen to the Star Drive-In, where they watch a film (Trenchard-Smith’s 1982 picture Escape 2000). As the film plays, they retreat to the back seat. Whilst Crabs and Carmen are mid-coitus, someone steals the wheels of the Chevy. Crabs speaks with the manager of the drive-in, Thompson (Peter Whitford), but discovers that he and Carmen are trapped. As the days progress, Crabs comes to the realisation that the drive-in functions as a concentration camp of sorts, containing those who are drawn to it like moths to a flame – mostly young, unemployed men and couples. The camp is presided over by Thompson, whose role is facilitated by the government and supported by the members of the police force who visit the camp from time to time.

As Crabs and Carmen spend more time at the drive-in, Crabs becomes increasingly desperate to escape; Carmen, however, settles comfortably into the strange, isolated community that has developed within the camp, forming friendships with the women there (many of whom prostitute themselves out to the men in the camp). Crabs encounters a number of cruel, thuggish young men, led by Dave (Dave Gibson). When a truckload of Chinese families are brought into the camp, Dave and the others subject the newcomers to racist abuse and form an anti-immigration society which gathers in the drive-in’s restaurant. During one of the group’s meetings, Crabs makes a daring, and final, attempt to escape.

The film continues the ongoing fascination with dystopic, often apocalyptic, futures envisioned in many science fiction films of the late 1970s and 1980s, from American pictures such as Damnation Alley (Jack Smight, 1977) and Escape from New York (John Carpenter, 1982); the wave of Italian postapocalyptic action pictures that followed Carpenter’s film, including Endgame—Bronx lotta finale (Joe D’Amato, 1983) and I nuovi barbari (The New Barbarians, Enzo G Castellari, 1983); and, of course, Australian films like Mad Max (George Miller, 1979), which also partially influenced the Italian pictures of the early 1980s. As Albert Moran and Errol Vieth note, the ‘cataclysm’ that leads to the dystopic future depicted within Dead End Drive-In is caused ‘not by nuclear war but from race wars in South Africa, a second crash on Wall Street and the associated economic anarchy’ (Moran & Vieth, 2006: 140). The opening sequence establishes the film’s continuity with the likes of Escape from New York, Endgame, Mad Max and even Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979), in which a present-day New York City is envisioned as a fantastical enclave of various colourful street gangs. Onscreen titles during the opening moments of Dead End Drive-In identify various natural disasters and signifiers of economic collapse that take place between 1988 and 1990, before the film takes us to the diegetic present: Crabs is shown jogging through the city, a red filter over the lens giving an otherworldly feel to the derelict, threatening urban landscape. Groups of young men are shown roaming the streets in jerry-rigged cars which look more like combat vehicles. These are the Karboys; they accost Crabs, but he manages to escape before returning home. The film continues the ongoing fascination with dystopic, often apocalyptic, futures envisioned in many science fiction films of the late 1970s and 1980s, from American pictures such as Damnation Alley (Jack Smight, 1977) and Escape from New York (John Carpenter, 1982); the wave of Italian postapocalyptic action pictures that followed Carpenter’s film, including Endgame—Bronx lotta finale (Joe D’Amato, 1983) and I nuovi barbari (The New Barbarians, Enzo G Castellari, 1983); and, of course, Australian films like Mad Max (George Miller, 1979), which also partially influenced the Italian pictures of the early 1980s. As Albert Moran and Errol Vieth note, the ‘cataclysm’ that leads to the dystopic future depicted within Dead End Drive-In is caused ‘not by nuclear war but from race wars in South Africa, a second crash on Wall Street and the associated economic anarchy’ (Moran & Vieth, 2006: 140). The opening sequence establishes the film’s continuity with the likes of Escape from New York, Endgame, Mad Max and even Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979), in which a present-day New York City is envisioned as a fantastical enclave of various colourful street gangs. Onscreen titles during the opening moments of Dead End Drive-In identify various natural disasters and signifiers of economic collapse that take place between 1988 and 1990, before the film takes us to the diegetic present: Crabs is shown jogging through the city, a red filter over the lens giving an otherworldly feel to the derelict, threatening urban landscape. Groups of young men are shown roaming the streets in jerry-rigged cars which look more like combat vehicles. These are the Karboys; they accost Crabs, but he manages to escape before returning home.

From the opening scenes, Crabs is contrasted with his brother Frank. Introduced jogging through the city, the puny Crabs envies Frank’s strength: Crabs is, in the words of the boys’ mother, ‘small like you’re papa. You’re never gonna be like Frank. He’s big and strong’. Given Crabs’ puny physique, when he and Carmen become trapped in the drive-in, he seems desperately vulnerable. His confrontations with Dave and his gang escalate to the point of violence, when Crabs becomes involved in a fight and, not having the strength of his brother Frank, manages to win the combat through tactics and guile. (It’s a fight that seems deliberately to recall the story of David and Goliath.)

As with Mad Max, cars are at the core of Dead End Drive-In: Crabs lusts after his brothers’ Chevy, seeing it as his ticket to seducing Carmen. When Frank lends Crabs the Chevy, Crabs’ date is initially successful (at least in terms of the goals of young men who date young women: in other words, he fucks Carmen in the back of the car) but almost immediately, this is undermined by the theft of the Chevy’s wheels (which takes place whilst Crabs and Carmen are mid-coitus). The fact that the car is an iconic American model, and that Crabs takes Carmen to a very American-style drive-in, highlights the extent to which Australia had, by the mid-1980s, become colonised by American culture and, particularly, the notion of the teenager or adolescent that was popularised by American popular culture during the 1950s. (That Dave wears his hair in a classic 1950s-style quiff reinforces this.) As with Mad Max, cars are at the core of Dead End Drive-In: Crabs lusts after his brothers’ Chevy, seeing it as his ticket to seducing Carmen. When Frank lends Crabs the Chevy, Crabs’ date is initially successful (at least in terms of the goals of young men who date young women: in other words, he fucks Carmen in the back of the car) but almost immediately, this is undermined by the theft of the Chevy’s wheels (which takes place whilst Crabs and Carmen are mid-coitus). The fact that the car is an iconic American model, and that Crabs takes Carmen to a very American-style drive-in, highlights the extent to which Australia had, by the mid-1980s, become colonised by American culture and, particularly, the notion of the teenager or adolescent that was popularised by American popular culture during the 1950s. (That Dave wears his hair in a classic 1950s-style quiff reinforces this.)

Rebecca Johinke has highlighted the similarities between the short story by Peter Carey on which the film is based and Franz Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’. By the end of Carey’s short story, Crabs has either transformed into a Ford V8 tow truck or else the reader might believe that he has been driven insane. As Johinke argues, ‘Crabs’s bodily transformation is just one of several shifts that occur in the story’: these include the titular drive-in, which is ‘a dynamic and shifting environment that refuses one reading as it mutates into a refugee camp and then into a prison’; the 1956 Dodge that Crabs borrows from his brother is ‘at first a symbol of sexual liberation and escape’ but as the narrative progresses ‘turns into a menacing and disintegrating cage’; Carmen ‘changes from being a desirable date into an unattractive burden’; the manager of the drive-in ‘becomes a prison warden and the police no longer represent justice but corruption’ (Johinke, 2002: 95). The car itself becomes a metaphor for both ‘human relationships, and Australian society’: all of them are ‘beyond repair’ (ibid.: 97).

The drive-in becomes a microcosm of society. Johinke has highlighted the relationships between the short story and Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, in terms of Crabs’ transformation into a tow truck at the end of the story; but the film also underlines this through its representation of Thompson as a Kafkaesque bureaucrat who ensnares Crabs as much through rhetoric as anything else. When Crabs visits Thompson the morning after the wheels of the Chevy have been stole, Crabs tells Thompson that he is there ‘to report a theft. Two wheels off me car’. ‘You were lucky’, Thompson tells him. ‘How am I supposed to get home?’, Crabs asks. ‘You can’t’, Thompson responds. ‘You mean, we’ll have to stop here all night?’, Crabs asks. ‘Not so bad, is it?’, Thompson responds, glancing lustfully at Carmen. The drive-in used as the principal location for the shooting of the film was the Star Drive-In at Matraville, which opened in 1958 and was part of the second generation of drive-ins that appeared in Australia. The Star closed in 1984; following its use as the principal location for Dead End Drive-In, the Star was demolished shortly after the completion of the film. The drive-in becomes a microcosm of society. Johinke has highlighted the relationships between the short story and Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, in terms of Crabs’ transformation into a tow truck at the end of the story; but the film also underlines this through its representation of Thompson as a Kafkaesque bureaucrat who ensnares Crabs as much through rhetoric as anything else. When Crabs visits Thompson the morning after the wheels of the Chevy have been stole, Crabs tells Thompson that he is there ‘to report a theft. Two wheels off me car’. ‘You were lucky’, Thompson tells him. ‘How am I supposed to get home?’, Crabs asks. ‘You can’t’, Thompson responds. ‘You mean, we’ll have to stop here all night?’, Crabs asks. ‘Not so bad, is it?’, Thompson responds, glancing lustfully at Carmen. The drive-in used as the principal location for the shooting of the film was the Star Drive-In at Matraville, which opened in 1958 and was part of the second generation of drive-ins that appeared in Australia. The Star closed in 1984; following its use as the principal location for Dead End Drive-In, the Star was demolished shortly after the completion of the film.

The drive-in, of course, functions as a concentration camp, attracting ‘undesirables’ (mostly unemployed, unproductive youths) and ensnaring them: Crabs is certain that the people who stole the wheels of Frank’s Chevy were not Karboys but were instead members of the police force. The other inhabitants, we may presume, have been trapped in the camp by the police acting in a similar manner. When Crabs and Carmen wake up the morning after the wheels of the Chevy have been stolen, they find that what under the cover of darkness appeared to be a normal drive-in resembles more closely a refugee camp: wrecked vehicles are dotted about, open fires blazing here and there, and the other people have the tattered, downtrodden appearance of refugees.

Much later in the film, new inmates arrive by the truckload: they are all Chinese. The inhabitants of the drive-in show their true colours, gathering together to rant against the ‘foreigners’ and express anti-immigration sentiments: though not stated directly, it may be inferred that these new inmates have been introduced as a means of managing the group dynamics, turning the attentions of the existing inhabitants away from the possibility of escape and towards their new group ‘enemy’ – the new arrivals. The existing inhabitants round on the new arrivals, legitimising their prejudice by suggesting that the newcomers are capable of nefarious deeds. ‘Asians out! Asians out!’, the inhabitants chant as the new arrivals are brought into the drive-in. The racist sentiments of the majority of the existing inhabitants are assimilated by Carmen, who tells Crabs ‘I don’t like being here with those’ – referring to the Chinese newcomers – ‘They could rape me or anything. If you were a man, you’d do something about it’. Crabs attempts to talk some sense into Carmen: ‘Listen, they’re not the enemy’, he tells her, ‘They’re prisoners, just like us’. ‘They should limit how many can come here’, Carmen asserts. ‘“Limit the numbers and everything will be great”’, Crabs says sarcastically: ‘Look around. This is a slum. Even with only a few people it would still be a slum [….] People can’t have a life here. All they can have is a heap of shit movies or go for a poisonous hamburger’. Carmen attempts to impress upon Crabs what she sees as the important project of ‘protecting’ the drive-in, which she has made her new home: ‘Jimmy, can’t you see? This is all we’ve got’, Carmen says. ‘I can see’, Crabs tells her, ‘That’s just the trouble’. Meanwhile, Dave forms an anti-immigration society, the White Australian Citizens Committee: ‘Us whites have got to stick together!’, Dave asserts after Crabs intervenes in Dave’s gang’s act of tormenting one of the new arrivals, ‘Otherwise we’re stuffed, aren’t we?’ Dave tells Crabs: ‘Stop acting like a turd. You’re a member of the white community. You’ve got responsibilities’. ‘They’re crazy’, Crabs asserts simply, when Carmen tells him that Dave has arranged a meeting of his new society at the restaurant. Much later in the film, new inmates arrive by the truckload: they are all Chinese. The inhabitants of the drive-in show their true colours, gathering together to rant against the ‘foreigners’ and express anti-immigration sentiments: though not stated directly, it may be inferred that these new inmates have been introduced as a means of managing the group dynamics, turning the attentions of the existing inhabitants away from the possibility of escape and towards their new group ‘enemy’ – the new arrivals. The existing inhabitants round on the new arrivals, legitimising their prejudice by suggesting that the newcomers are capable of nefarious deeds. ‘Asians out! Asians out!’, the inhabitants chant as the new arrivals are brought into the drive-in. The racist sentiments of the majority of the existing inhabitants are assimilated by Carmen, who tells Crabs ‘I don’t like being here with those’ – referring to the Chinese newcomers – ‘They could rape me or anything. If you were a man, you’d do something about it’. Crabs attempts to talk some sense into Carmen: ‘Listen, they’re not the enemy’, he tells her, ‘They’re prisoners, just like us’. ‘They should limit how many can come here’, Carmen asserts. ‘“Limit the numbers and everything will be great”’, Crabs says sarcastically: ‘Look around. This is a slum. Even with only a few people it would still be a slum [….] People can’t have a life here. All they can have is a heap of shit movies or go for a poisonous hamburger’. Carmen attempts to impress upon Crabs what she sees as the important project of ‘protecting’ the drive-in, which she has made her new home: ‘Jimmy, can’t you see? This is all we’ve got’, Carmen says. ‘I can see’, Crabs tells her, ‘That’s just the trouble’. Meanwhile, Dave forms an anti-immigration society, the White Australian Citizens Committee: ‘Us whites have got to stick together!’, Dave asserts after Crabs intervenes in Dave’s gang’s act of tormenting one of the new arrivals, ‘Otherwise we’re stuffed, aren’t we?’ Dave tells Crabs: ‘Stop acting like a turd. You’re a member of the white community. You’ve got responsibilities’. ‘They’re crazy’, Crabs asserts simply, when Carmen tells him that Dave has arranged a meeting of his new society at the restaurant.

Early in the film, Crabs and Carmen visit Thompson, who provides them with meal tickets and blankets and asserts his patriarchal authority by frequently addressing Crabs as ‘son’. ‘Wait a second’, Crabs demands, ‘What the fuck is going on? Why do we want meal tickets or blankets? We’re leaving today’. ‘How?’, Thompson asks. ‘We’ll get a bus’, Crabs responds. ‘There aren’t any buses’, Thompson tells him: ‘I’m not getting through to you, am I, son? No cabs, no buses, no transport. Just the “S” road. You can’t walk on an “S” road, can you? It’s illegal [….] You’re here until the government decides what to do with you’. Later, Crabs attempts to press Thompson, asking him ‘What’s the average stay here? [….] Till you get parts and piss off?’ Thompson tells Crabs: ‘You’re not listening, Jimmy, are you, son? There’s no parts and no market. You’re here. This is… your home’. Thompson sees Crabs as something of a rebel, an element of Crabs’ personality which manifests itself in his continuing desire to escape from the drive-in. Thompson tries to impress upon Crabs the futility of trying to escape and suggests that Crabs’ rebellious streak will dissipate with age (and with the realisation that he is unable to escape). ‘You want to kick against the system? Natural enough at your age. Well, I’ve been here a fair old while. I’m telling you it doesn’t pay, son’, Thompson says. ‘They must want to get out’, Crabs asserts in reference to the other inhabitants of the drive-in. ‘They know they can’t so they don’t worry about it. There’s no future in it’. In a later scene, Thompson speaks with Crabs and reflects on the golden age of the drive-in: ‘Those days were amazing’, Thompson says. ‘How long’s it [the drive-in] been like this?’, Crabs asks, referring to the drive-in’s current condition. ‘Like this? Well, it’s the state of things, son’, Thompson says, ‘Economic conditions’. Though Thompson sees Crabs as a rebel, and therefore someone to be ‘tamed’, he also sees the intelligence in Crabs that is lacking in the likes of Dave: ‘I don’t say this to most of the others’, Thompson tells Crabs, ‘They’re just dead-heads. I could find a place for a bloke like you. You got a bit going’. Early in the film, Crabs and Carmen visit Thompson, who provides them with meal tickets and blankets and asserts his patriarchal authority by frequently addressing Crabs as ‘son’. ‘Wait a second’, Crabs demands, ‘What the fuck is going on? Why do we want meal tickets or blankets? We’re leaving today’. ‘How?’, Thompson asks. ‘We’ll get a bus’, Crabs responds. ‘There aren’t any buses’, Thompson tells him: ‘I’m not getting through to you, am I, son? No cabs, no buses, no transport. Just the “S” road. You can’t walk on an “S” road, can you? It’s illegal [….] You’re here until the government decides what to do with you’. Later, Crabs attempts to press Thompson, asking him ‘What’s the average stay here? [….] Till you get parts and piss off?’ Thompson tells Crabs: ‘You’re not listening, Jimmy, are you, son? There’s no parts and no market. You’re here. This is… your home’. Thompson sees Crabs as something of a rebel, an element of Crabs’ personality which manifests itself in his continuing desire to escape from the drive-in. Thompson tries to impress upon Crabs the futility of trying to escape and suggests that Crabs’ rebellious streak will dissipate with age (and with the realisation that he is unable to escape). ‘You want to kick against the system? Natural enough at your age. Well, I’ve been here a fair old while. I’m telling you it doesn’t pay, son’, Thompson says. ‘They must want to get out’, Crabs asserts in reference to the other inhabitants of the drive-in. ‘They know they can’t so they don’t worry about it. There’s no future in it’. In a later scene, Thompson speaks with Crabs and reflects on the golden age of the drive-in: ‘Those days were amazing’, Thompson says. ‘How long’s it [the drive-in] been like this?’, Crabs asks, referring to the drive-in’s current condition. ‘Like this? Well, it’s the state of things, son’, Thompson says, ‘Economic conditions’. Though Thompson sees Crabs as a rebel, and therefore someone to be ‘tamed’, he also sees the intelligence in Crabs that is lacking in the likes of Dave: ‘I don’t say this to most of the others’, Thompson tells Crabs, ‘They’re just dead-heads. I could find a place for a bloke like you. You got a bit going’.

The other inhabitants of the drive-in submit to Thompson’s authority but secretly regard him with suspicion and distaste. ‘You wanna watch Thompson, mate’, Dave and his cronies tell Crabs during their first meeting, ‘He’s on their side’. Late, Dave offers drugs to Crabs (‘a touch of smack? Some speed?’), and Crabs refuses. Dave immediately believes Crabs’ negative response to his offer of narcotics is down to Thompson: ‘Thompson warn you off them, did he?’, Dave asks mockingly. His comments remind us that all of the inhabitants of the drive-in, regardless of whether they are an 'inmate' or, like Thompson, a figure of authority, are to a greater extent prisoners; in the context of the film's setting (the drive-in), this makes the film a delirious example of metafiction, reflecting on the capacity of popular culture to ensnare and entrap its audience, offering - like the Peter Carey story on which it is based - a nightmarish, Kafkaesque vision.

Video

Taking up approximately 24Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The film is uncut and runs for 86:59 mins, with the cuts previously imposed by the BBFC to the film’s 1987 VHS release waived, and the film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The 35mm colour photography is reproduced nicely here, with the image rich in depth and detail. The rich colour consistency of the presentation is demonstrated in the film’s opening sequence, which sees red filters used on the lenses to communicate the nightmarish urban setting. (Later in the picture, yellow filters are used to achieve a similar effect.) The presentation is clean and free of damage, and also free of any harmful digital tinkering. Excellent contrast is evident throughout, benefitting the film’s many nighttime sequences, offering depth to the shadows and strong midtones. A strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, with smoke and other particle effects handled nicely.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is clear, deep and bassy, the strong range evidenced from the music which plays under the film’s opening titles. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are error free and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with director Brian Trenchard-Smith. Trenchard-Smith introduces himself as someone who ‘enjoy[s] making “what if” films’. He talks about the short story by Peter Carey on which the film is based, and discusses his own career as a filmmaker. He suggests that ‘I enjoy exploring important themes in a wacky way’, and describes the picture as ‘part Mad Max, part Exterminating Angel’. There’s some detailed discussion of the shooting of the picture, but Trenchard-Smith is particularly lucid on highlighting the themes of the picture and comparing it with real life situations. - An audio commentary with director Brian Trenchard-Smith. Trenchard-Smith introduces himself as someone who ‘enjoy[s] making “what if” films’. He talks about the short story by Peter Carey on which the film is based, and discusses his own career as a filmmaker. He suggests that ‘I enjoy exploring important themes in a wacky way’, and describes the picture as ‘part Mad Max, part Exterminating Angel’. There’s some detailed discussion of the shooting of the picture, but Trenchard-Smith is particularly lucid on highlighting the themes of the picture and comparing it with real life situations.

- ‘The Stuntmen’ (48:46). In 1973, Brian Trenchard-Smith directed a one-off television documentary about the work of movie stuntmen. This documentary is included here. It’s a remarkable document, one which Trenchard-Smith used to drum up financing for his first feature film, The Man from Hong Kong (1975). Shot on film, this documentary is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The footage displays intermittent damage, but nothing that should detract from one’s enjoyment of the piece. It’s a superbly shot and edited piece, consisting of footage shot on the sets of numerous films – the sequences functioning like short movies in and of themselves – offering the viewer an insight into the work of stuntmen.

- ‘Hospitals Don’t Burn Down’ (24:10). Here, a 1978 public information film directed by Trenchard-Smith is included. This is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Again shot on film, it exhibits less damage than ‘The Stuntmen’. The film begins with a man secretly smoking in a hospital bed as a nurse visits the ward during her night rounds. She tells him to put his cigarette out. A sense of peril is introduced when the nurse visits the children’s ward. When a cigarette end is thrown by a patient into a laundry chute, as a means of circumventing the wrath of the sister in charge of the ward, a raging fire begins. When a nurse opens the hatch to the laundry chute, a backdraft causes the flames to burst out at her; her clothes catch fire. The fire service rush to the hospital to put out the fire, but the lives of the staff and patients are in great peril. It’s a tense, nightmarish short film with many elements in common with exploitation filmmaking.

- ‘Vladimir Cherepanoff Gallery’ (0:17).This stills gallery, featuring photographs interspersed with text, focuses on graffiti artists in Sydney, presented from the perspective of Cherepanoff – whose graffiti is featured in Dead End Drive-In.

- Trailer (1:36).

Overall

An interesting 1980s science fiction-action hybrid, in its exploration of a concentration camp scenario, Dead End Drive-In has clear parallels with Trenchard-Smith’s Escape 2000. Like that picture, Dead End Drive-In is a highly satirical film, its focus on anti-immigration rhetoric and xenophobic moral panics stirred up about ‘foreigners’ seeming very relevant to today. It’s a fun film, with strong echoes of the likes of The Warriors, Escape from New York and, of course, Mad Max. It’s also very nicely-shot, with some excellent and expressive photography. An interesting 1980s science fiction-action hybrid, in its exploration of a concentration camp scenario, Dead End Drive-In has clear parallels with Trenchard-Smith’s Escape 2000. Like that picture, Dead End Drive-In is a highly satirical film, its focus on anti-immigration rhetoric and xenophobic moral panics stirred up about ‘foreigners’ seeming very relevant to today. It’s a fun film, with strong echoes of the likes of The Warriors, Escape from New York and, of course, Mad Max. It’s also very nicely-shot, with some excellent and expressive photography.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a superb presentation of the main feature. Particularly in terms of contrast levels and the clarity of the film’s many nighttime sequences, this presentation represents a big improvement over the film’s previous home video releases. The presentation itself is accompanied by some very good supporting material which helps to give the film a strong sense of context. ‘The Stuntmen’ and ‘Hospitals Don’t Burn Down’ are worth the price of admission themselves. Arrow’s Blu-ray offers a very pleasing release of an ‘Ozploitation’ classic.

References:

Johinke, Rebecca, 2002: ‘Misogyny, Muscles and Machines: Cars and Masculinity in Australian Literature’. In: Callahan, David (ed), 2002: Contemporary Issues in Australian Literature. London: Routledge: 95-111

Moran, Albert & Vieth, Errol, 2006: Film in Australia: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press

|