|

The Film

The Glass Key (Stuart Heisler, 1942) The Glass Key (Stuart Heisler, 1942)

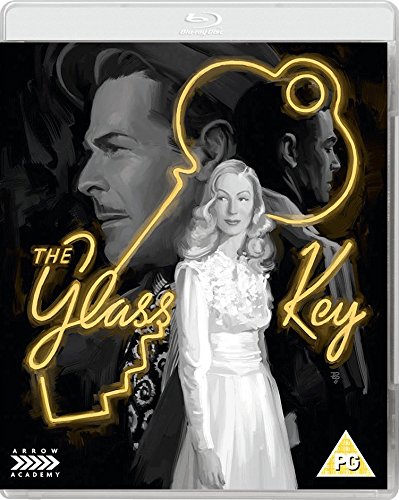

The second big screen adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel of the same title, Stuart Heisler’s The Glass Key (1942) followed Frank Tuttle’s 1935 film version which featured George Raft in the role of the story’s protagonist Ed Beaumont, and Edward Arnold as his friend, crooked politician Paul Madvig. Heisler’s adaptation casts Alan Ladd and Brian Donlevy in those roles, respectively. In the role of the film’s femme fatale, Janet Henry, the Heisler picture features Veronica Lake – whereas the 1935 film had Claire Dodd cast in the same role. In the casting of Ladd and Lake, the film sits between the other two pictures which featured the same two lead actors, This Gun for Hire (by the director of the first feature film adaptation of The Glass Key, Frank Tuttle, and released in 1942) and The Blue Dahlia (George Marshall, 1946). (The Coen Brothers’ 1990 noir pastiche Miller’s Crossing features a plot that cribs elements from Hammett’s The Glass Key, and stars Gabriel Byrne and Albert Finney in the Beaumont and Madvig roles, with Marcia Gay Harden as the femme fatale.)

Paul Madvig (Brian Donlevy), a mobster and head of the Voters’ League criticises the son of Ralph Henry (Moroni Olsen), a prospective candidate for Governor who is on a reform ticket. Following this, Madvig is confronted by Henry’s daughter Janet (Veronica Lake). Janet slaps Madvig, telling him ‘It’d do the state good if someone could reform you, right out of existence’. Of course, for Madvig it is love at first sight, and in response to this Madvig decides to back Ralph Henry for senator – hoping to get closer to Janet. This riles Madvig’s hoodlum associate Nick Varna (Joseph Calleia). Meanwhile, Madvig’s friend and enforcer Ed Beaumont (Alan Ladd) warns Madvig that he has allied himself with Henry for the wrong reasons, asking Madvig ‘How far has that dog [Janet] got her hooks into you?’

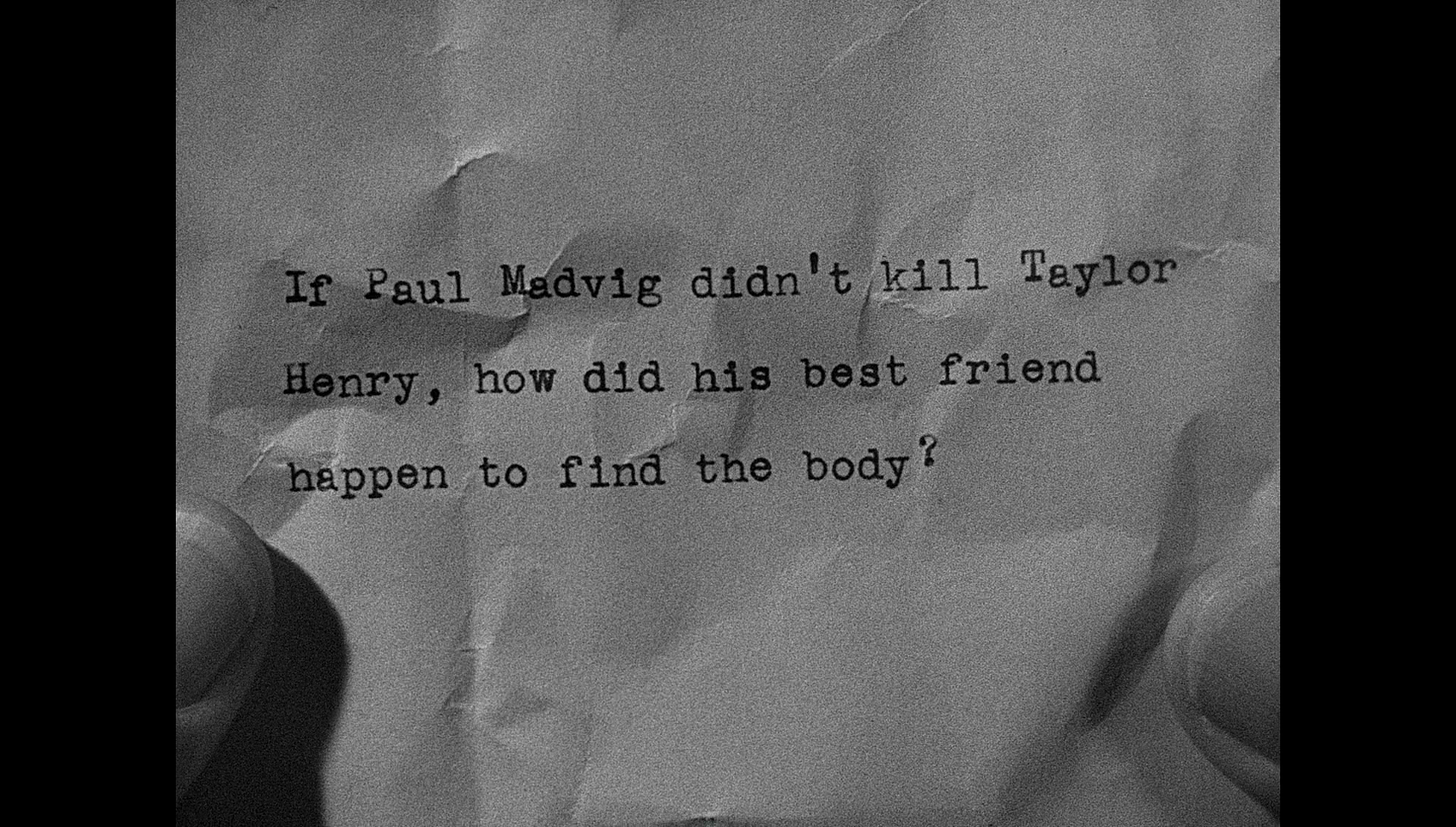

When Ed is introduced to the Henrys, Janet makes goo-goo eyes at him. However, knowing how much his friend Madvig is in love with Janet, Ed deflects her attention. When Ralph Henry’s son Taylor (Richard Denning), with whom Madvig has come into conflict over Taylor’s affair with Madvig’s sister Opal (Bonita Granville), winds up dead, even Ed begins to suspect that his old friend may have murdered the youth. However, Taylor owed money to Varna, and thus Varna seems a likely suspect too. When Ed is introduced to the Henrys, Janet makes goo-goo eyes at him. However, knowing how much his friend Madvig is in love with Janet, Ed deflects her attention. When Ralph Henry’s son Taylor (Richard Denning), with whom Madvig has come into conflict over Taylor’s affair with Madvig’s sister Opal (Bonita Granville), winds up dead, even Ed begins to suspect that his old friend may have murdered the youth. However, Taylor owed money to Varna, and thus Varna seems a likely suspect too.

Following Taylor Henry’s death, Varna attempts to lean on Madvig, suggesting that he will spread the rumour Madvig killed Taylor if Madvig doesn’t renege on his support for Ralph Henry. However, Madvig refuses to bow to the pressure Varna puts on him. Meanwhile, Janet has begun to suspect that Madvig may have killed her brother, and she asks Ed to help her ascertain whether or not Madvig is responsible for the crime. When Ed reports back to Madvig and questions his friend’s relationship with Janet, Madvig strikes Ed. With Ed and Madvig’s alliance apparently fractured, Varna approaches Ed and offers to ‘stake [him] the finest gambling place in town. Let you run it to suit yourself’ – if Ed will give Clyde Matthews (Arthur Loft), a newspaper owner in the pocket of Varna, ‘the lowdown on Paul’. Ed refuses, and finds himself held captive by Varna. Ed is beaten by Varna’s thugs, including the sadistic Jeff (William Bendix).

Starting a fire as a distraction, the badly injured Ed manages to escape from Varna and his thugs. Winding up in a hospital, Varna is visited by Madvig and informs Madvig of Varna’s plan to use Matthews’ newspaper and the testimony of a supposed witness to Taylor Henry’s death, a man named Henry Sloss (Dane Clark), to ruin Madvig’s reputation ahead of the election. After discharging himself from the hospital, Ed pays a visit to Cyril Matthews and finds Varna and his goons there. After Ed reveals to Matthews’ wife Eloise (Margaret Hayes) the plan Varna has concocted and Matthews’ role in it, Eloise expresses disgust at her husband. She and Ed sleep together, causing Matthews to commit suicide in the bedroom. Matthews leaves a note declaring Varna to be the executor of his will – and therefore enabling the attempt to slander Madvig via Matthews’ newspaper to go ahead. Ed burns this note in the fire. When Varna’s thugs round on Ed, Madvig enters and uses his fists to silence Varna’s goons.

Madvig seems to be on the path to victory, but things become complicated when Sloss is killed outside Madvig’s building – and the gunshot which killed Sloss seems to have come from the window of Madvig’s personal office. Following this, Madvig confesses to Ed that he did indeed kill Taylor Henry, but that it was an accident. However, Ed doesn’t believe this: Ed concludes that Madvig has confessed to the killing in order to protect the real culprit. Ed confronts Jeff, who displays resentment as to the way he’s allowed himself to be treated as hired muscle by men like Varna. (‘I’m just a big, good-natured slob’, Jeff tells Ed, ‘Anybody can push me about any way they want to. And I never do anything about it’.) When Varna intrudes, Jeff kills the gangster, strangling him to death whilst Ed watches on. With Varna’s involvement cleared up, Ed finds himself now shouldering the responsibility of identifying Taylor Henry’s real killer and clearing the name of Madvig. Madvig seems to be on the path to victory, but things become complicated when Sloss is killed outside Madvig’s building – and the gunshot which killed Sloss seems to have come from the window of Madvig’s personal office. Following this, Madvig confesses to Ed that he did indeed kill Taylor Henry, but that it was an accident. However, Ed doesn’t believe this: Ed concludes that Madvig has confessed to the killing in order to protect the real culprit. Ed confronts Jeff, who displays resentment as to the way he’s allowed himself to be treated as hired muscle by men like Varna. (‘I’m just a big, good-natured slob’, Jeff tells Ed, ‘Anybody can push me about any way they want to. And I never do anything about it’.) When Varna intrudes, Jeff kills the gangster, strangling him to death whilst Ed watches on. With Varna’s involvement cleared up, Ed finds himself now shouldering the responsibility of identifying Taylor Henry’s real killer and clearing the name of Madvig.

Madvig’s backing of the reform ticket represented by Henry’s campaign angers Varna, who protests that ‘Business is business, and politics is politics’. (For Varna, ‘business’ of course equates with criminal enterprise.) Varna has apparently bought protection from Madvig, but Madvig’s vow that ‘We’re gonna clean up this town’ threatens to drive Varna out of business: when Varna threatens Madvig over the latter’s support for Henry, Madvig picks up a telephone in his office and, in reference to the nightclubs Varna operates, tells the person on the other end to ‘Slam ‘em down so hard they splash’.

From the outset, Madvig is introduced as a hoodlum: ‘He’s the biggest crook in the state’, someone comments from the sidelines in one of the film’s opening scenes. He decides to use his clout to back Ralph Henry’s campaign for governor, despite the protestations of Ed. Ed asks Madvig, ‘Think he’ll [Henry will] play ball after election’. ‘I’m sure he will’, Madvig says confidently, ‘He’s practically given me the key to his mansion’. Ed’s response gives the film its title: ‘Yeah, glass key’, Ed says, ‘Be careful it doesn’t break off in your hand’. The symbolism of the glass key, something which opens doors but which is also incredibly fragile, has been the subject of much debate about both Hammett’s novel and this film adaptation, with interpretations revolving around ‘Ned’s [Ed’s] impotence, Janet’s guilt, the fragility of their “love,” human impermanence in general?’ (Gale, 2000: 91).

This fragility is something which runs counter to Madvig’s belief in muscle and sheer force. Dining with the Henry family, Madvig tells them ‘You know, politics is simple. All you need is a little muscle’. Janet finds Madvig’s character distasteful, but she’s willing to string him along in order to help her father – knowing that Madvig’s support will be integral to her father’s success in his campaign to win the governorship. After giving Ed the ‘come on’, she asks Ed how he can stand Madvig. ‘I get along with Paul because he’s on the dead up-and-up’, Ed tells her. Ed’s reason for suspecting Madvig has some involvement in the death of Taylor Henry revolves around Taylor’s affair with Madvig’s sister Opal, and Madvig’s disapproval of Taylor: ‘No sister of mine is going to be taken in by a cheap, chiseling playboy’, Madvig tells Opal early in the film, after she reminds him that ‘You’re supposed to be my brother, not a watchdog’. (Madvig’s over-involvement in his sister’s love affair might remind viewers of Alexander Mackendrick’s later film noir Sweet Smell of Success, 1957.) Madvig’s response when Ed tells him of the death of Taylor Henry is utterly hardboiled: ‘What do you want me to do, bust out crying?’, Madvig asks coldly whilst continuing with his morning routine. This fragility is something which runs counter to Madvig’s belief in muscle and sheer force. Dining with the Henry family, Madvig tells them ‘You know, politics is simple. All you need is a little muscle’. Janet finds Madvig’s character distasteful, but she’s willing to string him along in order to help her father – knowing that Madvig’s support will be integral to her father’s success in his campaign to win the governorship. After giving Ed the ‘come on’, she asks Ed how he can stand Madvig. ‘I get along with Paul because he’s on the dead up-and-up’, Ed tells her. Ed’s reason for suspecting Madvig has some involvement in the death of Taylor Henry revolves around Taylor’s affair with Madvig’s sister Opal, and Madvig’s disapproval of Taylor: ‘No sister of mine is going to be taken in by a cheap, chiseling playboy’, Madvig tells Opal early in the film, after she reminds him that ‘You’re supposed to be my brother, not a watchdog’. (Madvig’s over-involvement in his sister’s love affair might remind viewers of Alexander Mackendrick’s later film noir Sweet Smell of Success, 1957.) Madvig’s response when Ed tells him of the death of Taylor Henry is utterly hardboiled: ‘What do you want me to do, bust out crying?’, Madvig asks coldly whilst continuing with his morning routine.

Heisler’s adaptation was scripted by Jonathan Latimer, who like Hammett was an author of hardboiled crime novels; during the 1930s, Latimer had written five novels featuring the Sam Spade-alike private detective Bill Crane. Jim Hillier has suggested that coming early in the cycle of classic films noir, a year after the film most commonly claimed to have initiated the noir style (John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, 1941), The Glass Key ‘can be defined as an early film noir less for its visual style than for its repertory of themes about corruption and wealth’ (Hillier, 2009: 106). Certainly, one of the aspect of later films noir that is consolidated here is the representation of the femme fatale, as embodied by Veronica Lake. Throughout the film, Janet Henry is represented ambiguously: the object of Madvig’s affections, she tries to seduce his friend Ed. However, Ed refuses her advances, noting the cultural differences between them: ‘You’ve got a pretty face, nice manners’, he tells her, ‘but I wouldn’t trust you outside this room. You’re slumming, and I don’t go for slummers. You think you’re too good for me – but sister, I’m too good for you’.

Veronica Lake was less than enthusiastic about The Glass Key, later referring to her and Ladd’s lack of enthusiasm for the picture by stating that ‘Alan and I attacked the project with all the enthusiasm of time clock employees, a pretty cocky approach for two people without acting credentials and only the instant star system to thank for our success’ (Lake, quoted in Mooney, 2014: 148). Throughout the film, Janet Henry pursues Ed, who through dedication towards his friend Madvig (who is in love with Janet) resists her advances until, somewhat unconvincingly, at the end of the film he relents. In their various interactions, Ed and Janet share sharp, pithy dialogue: William H Mooney suggests that the ‘banter’ between the pair ‘reflects the competition between them, a bristling style of dialogue that remained current in film noir, bitterly sarcastic and showing the defensive isolation of frightened people in a dangerous world’ (ibid.).

As Madvig, Donlevy carries some of what Jim Hillier describes as the ‘comic, dumb-lug governor-by-accident’ role Donlevy played in The Great McGinty (Preston Sturges, 1940), marrying this with elements of ‘a 1930s style mobster’ (Hillier, op cit.: 106). In contrast with this, Ladd’s Ed Beaumont is ‘strikingly modern – isolated and inward-looking’ (ibid.). Hillier notes that one of the most ‘striking element[s]’ within the film is the ‘ambiguity’ surrounding Beaumont’s sexuality: although women, including Janet Henry, throw themselves at him throughout the picture, Beaumont rebuffs them and remains doggedly affiliated with Madvig, his dedication to his friend offering space for the viewer to read into their relationship something more than mere fraternity (ibid.). Like Wilmer in Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1929), Ed may be considered a gunsel: one might be reminded of Hammett’s use of that word, referring to a young man involved in a sexual relationship with an older male, in The Maltese Falcon, knowing that the editor of Black Mask (the magazine in which the novel was serialised) would naively mistake it for a reference to a hoodlum who carries a gun and therefore allow it in the publication. (The word was also used in John Huston’s 1941 film adaptation of the same novel, its use in that film again presumably permitted by the Production Code Authority because they were naïve as to its actual meaning.) This is compounded when acting under the orders of Varna, Jeff beats Beaumont, Jeff’s repeated use of the words ‘sweetheart’, ‘sweetie-pie’ and ‘baby’ to refer to Beaumont combined with intimations of sado-masochistic pleasure in the dialogue: ‘He likes it. Don’t you, baby?’, Jeff taunts Beaumont (ibid.). When Latimer’s script for the film was submitted to the Breen office for approval, one of the items that Breen demanded be omitted from the shooting script was a line from Jeff referring to Beaumont as ‘a goddamned massacrist’, a line straight out of Hammett’s novel. (‘Massacrist’ is, obviously, a mangling of ‘masochist’.) As Madvig, Donlevy carries some of what Jim Hillier describes as the ‘comic, dumb-lug governor-by-accident’ role Donlevy played in The Great McGinty (Preston Sturges, 1940), marrying this with elements of ‘a 1930s style mobster’ (Hillier, op cit.: 106). In contrast with this, Ladd’s Ed Beaumont is ‘strikingly modern – isolated and inward-looking’ (ibid.). Hillier notes that one of the most ‘striking element[s]’ within the film is the ‘ambiguity’ surrounding Beaumont’s sexuality: although women, including Janet Henry, throw themselves at him throughout the picture, Beaumont rebuffs them and remains doggedly affiliated with Madvig, his dedication to his friend offering space for the viewer to read into their relationship something more than mere fraternity (ibid.). Like Wilmer in Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1929), Ed may be considered a gunsel: one might be reminded of Hammett’s use of that word, referring to a young man involved in a sexual relationship with an older male, in The Maltese Falcon, knowing that the editor of Black Mask (the magazine in which the novel was serialised) would naively mistake it for a reference to a hoodlum who carries a gun and therefore allow it in the publication. (The word was also used in John Huston’s 1941 film adaptation of the same novel, its use in that film again presumably permitted by the Production Code Authority because they were naïve as to its actual meaning.) This is compounded when acting under the orders of Varna, Jeff beats Beaumont, Jeff’s repeated use of the words ‘sweetheart’, ‘sweetie-pie’ and ‘baby’ to refer to Beaumont combined with intimations of sado-masochistic pleasure in the dialogue: ‘He likes it. Don’t you, baby?’, Jeff taunts Beaumont (ibid.). When Latimer’s script for the film was submitted to the Breen office for approval, one of the items that Breen demanded be omitted from the shooting script was a line from Jeff referring to Beaumont as ‘a goddamned massacrist’, a line straight out of Hammett’s novel. (‘Massacrist’ is, obviously, a mangling of ‘masochist’.)

Ed is beaten brutally by Jeff; this pivotal torturing of the film’s hero is pure Hammett, and features heavily in other films based on Leone’s work: for example, Sergio Leone’s loose adaptation of Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest as a western all’italiana (Italian-style Western), A Fistful of Dollars (1964), in which after arriving in a small town and playing one side off against the other, the nameless protagonist (Clint Eastwood) finds himself captured by Ramon Rojo (Gian Maria Volonte) and beaten cruelly by his henchmen. (Leone’s subsequent westerns all’italiana, 1965’s For a Few Dollars More and 1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly would feature similar pivotal sequences in which the anti-hero is – almost masochistically – beaten, each film seemingly upping the ante in terms of the level of sadism on display.) When, later in The Glass Key, Ed and Jeff encounter one another in a bar, Jeff proposes a rehashing of their previous encounter which is wrapped in the rhetoric of seduction: ‘I got just the place for me and you upstairs’, Jeff tells Ed, ‘A room that’s too little for you to fall down in. I can bounce you around off the walls’. He continues, telling the others around him ‘Excuse us, gents, but we [Jeff and Ed] gotta go up and rehearse our act – me and my “sweetheart”’. Ed is beaten brutally by Jeff; this pivotal torturing of the film’s hero is pure Hammett, and features heavily in other films based on Leone’s work: for example, Sergio Leone’s loose adaptation of Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest as a western all’italiana (Italian-style Western), A Fistful of Dollars (1964), in which after arriving in a small town and playing one side off against the other, the nameless protagonist (Clint Eastwood) finds himself captured by Ramon Rojo (Gian Maria Volonte) and beaten cruelly by his henchmen. (Leone’s subsequent westerns all’italiana, 1965’s For a Few Dollars More and 1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly would feature similar pivotal sequences in which the anti-hero is – almost masochistically – beaten, each film seemingly upping the ante in terms of the level of sadism on display.) When, later in The Glass Key, Ed and Jeff encounter one another in a bar, Jeff proposes a rehashing of their previous encounter which is wrapped in the rhetoric of seduction: ‘I got just the place for me and you upstairs’, Jeff tells Ed, ‘A room that’s too little for you to fall down in. I can bounce you around off the walls’. He continues, telling the others around him ‘Excuse us, gents, but we [Jeff and Ed] gotta go up and rehearse our act – me and my “sweetheart”’.

Towards the climax, like many anti-heroes of Hammett’s fiction, Beaumont acts extremely coldly, seducing the wife (Margaret Hayes) of newspaper magnate Clyde Matthews under her husband’s gaze, thus driving Clyde to suicide and removing one obstacle from his quest to validate Madvig’s innocence in the killing of Taylor Henry. (This relationship has echoes of psychopath Rudy’s abduction of veterinarian Harold and his wife Fran in Jim Thompson’s later 1958 novel The Getaway, Rudy’s seduction of Fran in front of her husband causing Harold to kill himself.) In Hammett’s novel, Ed is active in his seduction of Eloise Matthews; this 1942 film adaptation makes Eloise a more active participant in this spectacle. Some of this shift in focus was down to the Production Code Authority, who told the filmmakers that Ed Beaumont ‘must not be shown kissing Mrs Matthews, although it will be acceptable to she her as playing up to him’ (PCA communication, quoted in Mooney, op cit.: 146). In the finished film, a kiss does indeed take place between Ed and Eloise Matthews, ‘though only after she clearly invites him to [kiss her]’ (ibid.). Ed also stands by and fails to intervene when Jeff turns on Varna, slowly throttling the mobster to death.

Video

Taking up approximately 19Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, this 1080p presentation of The Glass Key uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, and runs for 85:20 mins. The 35mm monochrome photography is presented here with very strong tonality: rich midtones with strong definition are complimented by deep shadows. Contrast is balanced nicely, and there is an excellent level of detail. The presentation is very clean and predominantly free from damage – other than the very occasional flecks and specks which suggest debris on the negative. The presentation is also free from harmful digital tinkering, and an impressive encode ensures that the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is bassy and rich, displaying a strong sense of range. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are free of errors and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes:

- Audio commentary with Barry Forshaw. In his commentary, Forshaw begins by discussing Dashiell Hammett’s work, suggesting that today ‘it’s hard’ to ‘appreciate the importance of the pulps’ and also the cynicism with which they were regarded during the 1920s and 1930s. He reflects on the importance of the pulp magazines in establishing the paradigms of hardboiled fiction generally, and how this helped to inform the classic films noir of the 1940s and 1950s. Forshaw suggests that Hammett’s ‘most important’ novel is Red Harvest, and he comments on some of the film adaptations of that book. Forshaw reflects on the relationship between Ed and Paul, and comments on the input of Heisler and the film’s screenwriter Jonathan Latimer.

- ‘Coming and Goings’ (23:28). Here, Alastair Phillips discusses the film, contextualising it through a discussion of the first film adaptation of The Glass Key and the success of Huston’s The Maltese Falcon. Phillips talks about the photography and considers some of the themes of the picture. He also talks about the performances, reflecting on Ladd’s role as Ed Beaumont – suggesting that this character is ‘a witness, along with the camera, of the more intensified sexual relationships that form the main undercurrent of the film’s narrative’ such as Opal’s relationship with Taylor Henry, and Madvig’s relationship with Janet Henry.

- Radio Dramatisation (29:39). This is, in its entirety, the 1946 radio dramatisation of Hammett’s novel, featuring Ladd, Marjorie Reynolds (as Janet Henry) and Ward Bond (as Madvig).

- Gallery (0:11).

- Trailer (1:37).

Overall

Easily eclipsing the 1935 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel, The Glass Key is an impressive, early example of classic film noir. It perhaps pales in comparison with John Huston’s adaptation of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, released the year prior, but nevertheless it’s a strong, morally complex work with some fantastic hardboiled dialogue. Donlevy is superb in a role that echoes his performance in Preston Sturges’ The Great McGinty, and the pairing of Ladd and Lake is as effective here as it was in This Gun for Hire and would be in the later The Blue Dahlia. Given some of the content, it’s surprising the film passed the Production Code Authority. Easily eclipsing the 1935 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel, The Glass Key is an impressive, early example of classic film noir. It perhaps pales in comparison with John Huston’s adaptation of Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, released the year prior, but nevertheless it’s a strong, morally complex work with some fantastic hardboiled dialogue. Donlevy is superb in a role that echoes his performance in Preston Sturges’ The Great McGinty, and the pairing of Ladd and Lake is as effective here as it was in This Gun for Hire and would be in the later The Blue Dahlia. Given some of the content, it’s surprising the film passed the Production Code Authority.

Arrow’s presentation of The Glass Key is excellent and will undoubtedly be deeply pleasing for aficionados of film noir. The impressive main presentation is supported by some excellent contextual material, making this a must-buy release of an important example of the film noir style.

References:

Gale, Robert L, 2000: A Dashiell Hammett Companion. London: Greenwood Press

Hillier, Jim, 2009: ‘The Glass Key’. In: Hillier, Jim & Phillips, Alastair (eds), 2009: BFI Screen Guides: 100 Film Noirs. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 106-7

Mooney, William H, 2014: Dashiell Hammett and the Movies. Rutger University Press

|