|

|

Ley Lines AKA Nihon kuroshakai (Blu-ray)

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th January 2017). |

|

The Film

‘The Black Society Trilogy’: Shinjuku Triad Society (1995), Rainy Dog (1997) and Ley Lines (1999) ‘The Black Society Trilogy’: Shinjuku Triad Society (1995), Rainy Dog (1997) and Ley Lines (1999)

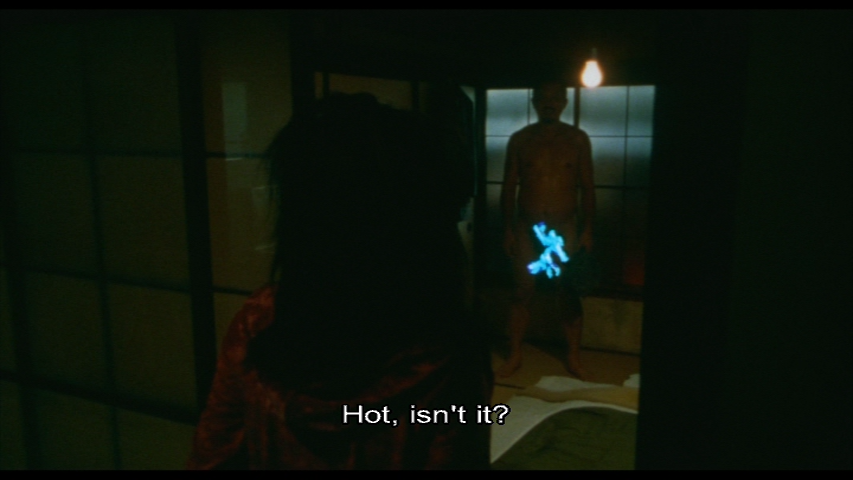

Made prior to Audition (1999, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of this film has been reviewed by us here), the ‘breakout’ film which established its incredibly prolific director Miike Takashi amongst non-Japanese audiences owing to its critical success in other countries, the three films gathered here – grouped under the label ‘the Black Society Trilogy’ (or kuroshakai trilogy) – characterise the focus of Miike’s pre-Audition pictures on the lives of yakuza members. The progression of the films also traces Miike’s approach to cinematic convention: all three pictures are combative in their sensibilities, and with each picture in the series Miike seems to escalate his war against convention, each subsequent film pushing against the paradigms of the genre and of cinema itself. Ley Lines (1999), the final film in the trilogy, openly parodies the censorship of ‘V-Cinema’ (the direct-to-video films in which Miike cut his teeth as a filmmaker), via the use of visually distracting optical censorship of nudity and grating beeps on the audio track whenever a character uses bad language; Ley Lines also seems to abandon conventional ideas about narrative structure. Released in the same year as Audition, Ley Lines thus seems to represent a transitional film for Miike, easing the director into his highly idiosyncratic post-millennial films such as Visitor Q (2001) and The Happiness of the Katakuris (2001, released on Blu-ray via Arrow and reviewed by us here).  About a decade or so ago, I used to present an annual lecture on fin-de-siècle cinema and, during this lecture, would show the opening sequence from Miike’s Dead or Alive (also released in 1999) as evidence of a fin-de-siècle spirit within cinema: rebellious, anti-authoritarian, subjectivist, characterised by a desire to shake up or abandon convention, breaking with the weight of the past and therefore liberating its audience’s expectations, and focused on a cynical representation of decadence and an emphasis on the carnivalesque. The lecture invariably bought Miike a few new ardent followers, something which I considered an achievement. Certainly, in their exploration of fin-de-siècle anxieties there were parallels in this sense between Miike’s pictures and some of the films made in Hong Kong around or during the period of the handover and expressing an anxiety about the future of the territory under Chinese rule; these films – such as Gordon Chan’s Beast Cops (1998) and Johnnie To’s films The Longest Nite (1998) and Expect the Unexpected (1998, both co-directed with Patrick Yau), and Wong Kar-Wai’s Fallen Angels (1995) and Happy Together (1997) – deal with issues of identity (for example, in their examination of the conflict between Hong Kong and Mainland China, an ongoing conflict between essentialism versus hybridity) and migration. These themes are integral to Miike’s Black Society Trilogy too, with all three pictures of this series focusing on a theme of identity and displacement via protagonists who have either a dual identity or who are positioned as outsiders within communities which reject them owing to their identity as a ‘foreigner’. (These themes would form a part of other Miike pictures such as City of Lost Souls (2000) and Bird People in China (1998).) Chris Desjardins has suggested that taken as a whole, the Black Society Trilogy ‘encapsulate[s] the cultural, economic and psychological reverberations form the collision of Japanese and Chinese underworlds’ (Desjardins, 2005: 190). About a decade or so ago, I used to present an annual lecture on fin-de-siècle cinema and, during this lecture, would show the opening sequence from Miike’s Dead or Alive (also released in 1999) as evidence of a fin-de-siècle spirit within cinema: rebellious, anti-authoritarian, subjectivist, characterised by a desire to shake up or abandon convention, breaking with the weight of the past and therefore liberating its audience’s expectations, and focused on a cynical representation of decadence and an emphasis on the carnivalesque. The lecture invariably bought Miike a few new ardent followers, something which I considered an achievement. Certainly, in their exploration of fin-de-siècle anxieties there were parallels in this sense between Miike’s pictures and some of the films made in Hong Kong around or during the period of the handover and expressing an anxiety about the future of the territory under Chinese rule; these films – such as Gordon Chan’s Beast Cops (1998) and Johnnie To’s films The Longest Nite (1998) and Expect the Unexpected (1998, both co-directed with Patrick Yau), and Wong Kar-Wai’s Fallen Angels (1995) and Happy Together (1997) – deal with issues of identity (for example, in their examination of the conflict between Hong Kong and Mainland China, an ongoing conflict between essentialism versus hybridity) and migration. These themes are integral to Miike’s Black Society Trilogy too, with all three pictures of this series focusing on a theme of identity and displacement via protagonists who have either a dual identity or who are positioned as outsiders within communities which reject them owing to their identity as a ‘foreigner’. (These themes would form a part of other Miike pictures such as City of Lost Souls (2000) and Bird People in China (1998).) Chris Desjardins has suggested that taken as a whole, the Black Society Trilogy ‘encapsulate[s] the cultural, economic and psychological reverberations form the collision of Japanese and Chinese underworlds’ (Desjardins, 2005: 190).

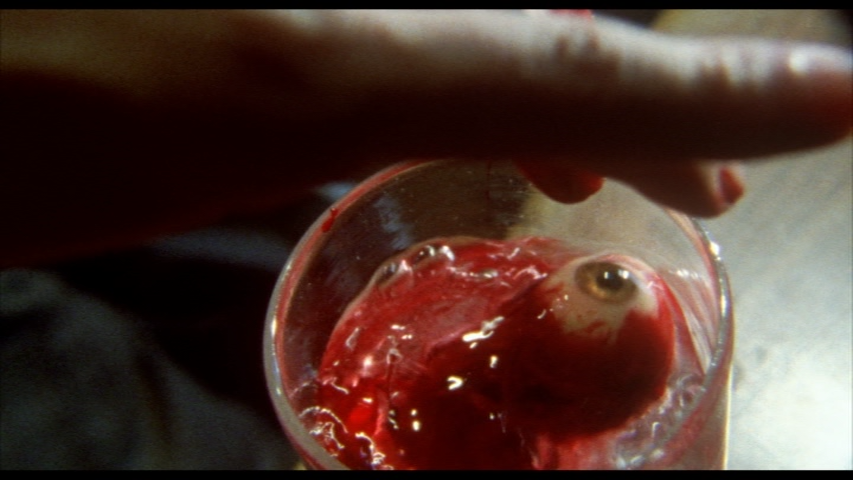

The first film in this trilogy, Shinjuku Triad Society (1995) was also the first film Miike made for theatrical release. Prior to this picture, Miike’s work (he had directed twelve films prior to this one) had been within the world of V-Cinema, a context in which Miike learnt to work quickly and efficiently – qualities which characterise his approach to cinema even to the present day.  Shinjuku Triad Society focuses on a detective, Kiriya Tatsuhito (Shina Kippei). Tatsuhito is a man out of place, born in China to a Japanese father and now living in Japan. Tatsuhito has a brother, Yoshihito, who has fallen in with Chinese criminal Wang (Taguchi Tomorowo). Wang presides over a brutal criminal organisation, the Dragon’s Claw Society, using his androgynous lover Zhou to act as the agent of his will, killing those who stand in his way. Tatsuhito begins an investigation of Wang’s group following the murder of a police officer by Zhou. Meanwhile, Tatsuhito is in the pay of a yakuza group, headed by a man named Uchida, feeding them confiscated ‘scag’ in exchange for payment. However, owing to his dual heritage Tatsuhito is kept at arm’s length by both his employers and the yakuza. Over time, it becomes clear that Yoshihito has become Wang’s lover, and with the knowledge of this – and with the aim of saving face for his ailing and elderly parents – Tatsuhito struggles to extract his brother from the Dragon’s Claw Society. Tatsuhito travels to Taiwan, Wang’s birthplace, in order to investigate his prey, and discovers that Wang is involved in forced organ harvesting. Returning to Japan, Wang persuades an associate of the Dragon’s Claw Society, the prostitute Ritsuko, to assist him in bringing down Wang’s organisation and thereby freeing Yoshihito. Shinjuku Triad Society focuses on a detective, Kiriya Tatsuhito (Shina Kippei). Tatsuhito is a man out of place, born in China to a Japanese father and now living in Japan. Tatsuhito has a brother, Yoshihito, who has fallen in with Chinese criminal Wang (Taguchi Tomorowo). Wang presides over a brutal criminal organisation, the Dragon’s Claw Society, using his androgynous lover Zhou to act as the agent of his will, killing those who stand in his way. Tatsuhito begins an investigation of Wang’s group following the murder of a police officer by Zhou. Meanwhile, Tatsuhito is in the pay of a yakuza group, headed by a man named Uchida, feeding them confiscated ‘scag’ in exchange for payment. However, owing to his dual heritage Tatsuhito is kept at arm’s length by both his employers and the yakuza. Over time, it becomes clear that Yoshihito has become Wang’s lover, and with the knowledge of this – and with the aim of saving face for his ailing and elderly parents – Tatsuhito struggles to extract his brother from the Dragon’s Claw Society. Tatsuhito travels to Taiwan, Wang’s birthplace, in order to investigate his prey, and discovers that Wang is involved in forced organ harvesting. Returning to Japan, Wang persuades an associate of the Dragon’s Claw Society, the prostitute Ritsuko, to assist him in bringing down Wang’s organisation and thereby freeing Yoshihito.

The second film, Rainy Dog (1997), revolves around Yujiro (Aikawa Sho), a Japanese hitman who is in exile in Taipei. When he receives news that his brother has taken over as the boss of a yakuza clan, following the death of the previous ‘don’, Yujiro is told that he will not be able to return to Japan. Yujiro resigns himself to being trapped in Taipei. Things become more complicated when a woman visits Yujiro and leaves with him a young child, Ah-Chen (He Jianqin), who she claims to be Yujiro’s child. Ah-Chen is mute. In Taipei, Yujiro takes orders from local Triad boss Mr Ke. Mr Ke commands Yujiro to assassinate a traitor within Mr Ke’s gang, and Yujiro obeys, killing the gangster under the gaze of Ah-Chen – who has been following Yujiro, regardless of Yujiro’s disinterest in the boy. After Yujiro encounters another Japanese gangster in exile, a rival hitman who tells Yujiro ‘I’ll get you eventually. It’s my job’, Mr Ke commands Yujiro to kill another man, Chiping Ku. Yujiro makes his first attempt at the job but stops when it begins to rain: Yujiro has a superstition about rain, believing it to bring bad luck, and thus refuses to work whilst it is raining. Yujiro takes a detour, spending the night with a prostitute, Lily (Chen Xianmei), whilst Ah-Chen sleeps in the street outside.  The next day, Yujiro resumes his task and executes his target, stealing money from the gangster and returning to Lily with it – having listened during the previous night to Lily’s dreams of escaping from her life as a prostitute. However, Yujiro’s victim’s brother seeks revenge against Yujiro, vowing that ‘They won’t get away from me. The man, the girl and the kid. Kill them all’. He contacts Mr Ke, who tells Chiping Ku’s brother where Yujiro is hiding. Yujiro, Ah-Chen and Lily escape to the coast, where they live a strange existence for a while during which the woman and the boy manage to humanise Yujiro. However, this brief respite begins to fall apart once the gangsters close in on Yujiro and his new surrogate family. The next day, Yujiro resumes his task and executes his target, stealing money from the gangster and returning to Lily with it – having listened during the previous night to Lily’s dreams of escaping from her life as a prostitute. However, Yujiro’s victim’s brother seeks revenge against Yujiro, vowing that ‘They won’t get away from me. The man, the girl and the kid. Kill them all’. He contacts Mr Ke, who tells Chiping Ku’s brother where Yujiro is hiding. Yujiro, Ah-Chen and Lily escape to the coast, where they live a strange existence for a while during which the woman and the boy manage to humanise Yujiro. However, this brief respite begins to fall apart once the gangsters close in on Yujiro and his new surrogate family.

In Ley Lines, following a series of missteps, petty criminal Ryuichi (Kazuji Kitamura) and his more studious brother Shunrei (Michisuke Kashiwatani), both of whom are of Japanese-Chinese heritage, make their way to Tokyo, along with their friend Chang (Yasuburo Itou). There, they find themselves targeted and exploited by prostitute Anita (Li Dan). Desperate to make a living for themselves, the trio become involved in selling a drug, the intoxicative inhalant toluene, on the city streets for low-ranking crook Ikeda (Sho Aikawa). Attempting to score fake passports which will allow them to flee Japan for a new life in Brazil, the trio encounter money-lender Wong (Naoto Takenaka). They plot to rob Wong at gunpoint, using his money to buy their way out of the country and establish themselves elsewhere, but Wong is tipped off by his associate Barbie (Samuel Pop Aning) and Ryuichi, his brother and his friends find themselves targeted by the gangster.  Shinjuku Triad Society is framed by two moments of voiceover narration about which there is some ambiguity: issues, in previous releases, with the English subtitling of these points of narration have led to some confusion over the identity of the narrator. Whereas Arrow’s new release, which contains subtitling which is apparently closer to the Japanese dialogue, suggests that the narrator is Tatsuhito’s brother, previous English-friendly home video releases apparently mistranslated the subtitles for the closing moment of narration and thereby suggested that the narrator was another character entirely. Shinjuku Triad Society is framed by two moments of voiceover narration about which there is some ambiguity: issues, in previous releases, with the English subtitling of these points of narration have led to some confusion over the identity of the narrator. Whereas Arrow’s new release, which contains subtitling which is apparently closer to the Japanese dialogue, suggests that the narrator is Tatsuhito’s brother, previous English-friendly home video releases apparently mistranslated the subtitles for the closing moment of narration and thereby suggested that the narrator was another character entirely.

In the opening moments of the film, the narrator tells us ‘The Dragon’s Claw Society is the name of our organisation. I am a member, and my boss is called Wang. I know a love story that’s both sickening and sweet. That’s how love is’. This last sentence could form as a mission statement for Miike’s representation of the concept of love throughout his films, which – as the narrator of this film suggests – invariably depict that emotion as simultaneously ‘sweet’ and ‘sickening’, an approach which runs counter to much of cinema’s representation of love and romance. Like the other protagonists of the films within the Black Society Trilogy, Tatsuhito lives in a liminal space: seeing himself as neither Japanese nor Chinese, his status as one or the other questioned by those around him. When Wang abducts Tatsuhiro and threatens to ‘harvest’ his kidneys, Tatsuhiro resists angrily: ‘Don’t touch Yoshihiro’, Tatsuhiro warns the gangster, ‘He’s my family. In that shithole of a village [in China, where the brothers were raised], on the coldest day in the coldest winter, we were kicked into a pig pen because we have Japanese blood in us. All thefts were blamed on us, two brothers’. This internal conflict and sense of displacement comes to a head when, investigating Wang, Tatsuhito travels to Taiwan searching for information and witnesses the poverty and simplicity of rural life in that country. Coming to see life in rural Taiwan as idyllic, Tatsuhiro finds himself absent-mindedly singing along with a local man who voices a song about the pleasures of rural life, something which is in stark contrast with the urgency and violence of life in urban Japan.  Along with this theme of migration and cultural conflict, Miike foregrounds clashes in language. Japanese and multiple Chinese dialects are used in the picture, the characters often struggling to understand one another. In the opening sequence, the murder of a uniformed police officer by Wang’s androgynous underling results in client that this rent boy’s ‘serviced’ prior to the killing being interrogated by the police. Tatsuhito questions this Chinese man with the use of an interrogator, but the interrogator asserts the difficulties in translating what the hostile witness is saying owing to the fact that he (the witness) is speaking in Min Nan dialect. Along with this theme of migration and cultural conflict, Miike foregrounds clashes in language. Japanese and multiple Chinese dialects are used in the picture, the characters often struggling to understand one another. In the opening sequence, the murder of a uniformed police officer by Wang’s androgynous underling results in client that this rent boy’s ‘serviced’ prior to the killing being interrogated by the police. Tatsuhito questions this Chinese man with the use of an interrogator, but the interrogator asserts the difficulties in translating what the hostile witness is saying owing to the fact that he (the witness) is speaking in Min Nan dialect.

The film is deeply brutal and blacky comic. Very early in the picture, we are shown a crime scene. The flash of the police photographer’s camera illuminates the scene, showing us the image of a grinning police officer holding a severed head. Later, the film goes to great lengths to highlight a similar level of brutality in both Wang’s crimes and Tatsuhito’s attempts to ensnare Wang: Tatsuhito has a male suspect raped in order to extract information about Wang, and Tatsuhito himself sodomises Ritsuko as a method of ‘persuading’ her to inform on Wang. In a manner that no doubt will alienate some viewers but which is typical of Miike’s combative approach, Ritsuko goes on to respond positively to the rape that Tatsuhito enacts upon her, later freeing the detective when he is captured by Wang and reflecting on their ‘encounter’ by suggesting that when Tatsuhito raped her anally, she experienced her first true orgasm(!) ‘It was the first time I came without being high’, Ritsuko sighs after untying Tatsuhito. Later, she mounts the badly injured Tatsuhito whilst he is in no condition to consent, in effect raping him. As the film progresses, the audience may begin to develop a sense of sympathy for the cruel Wang when they discover that Wang is haunted by his own murder of his father – to the extent that through Zhou’s eyes, we see Wang washing his hands obsessively and declaring ‘It won’t come off… The blood of my father’, in the manner of Lady Macbeth.  Another man out of place, Yujiro – the protagonist of Rainy Dog – finds himself completely exiled by his brother’s ascension to the role of head of a yakuza clan. Via a telephone call, Yujiro’s brother breaks this news to him, telling Yujiro ‘I’m taking over. So that leaves you with no place to go’. ‘You’ve done for me, brother’, Yujiro reflects in his voiceover, ‘Really done for me [….] What a fucking mess!’ Yujiro is patronised by local gangster Mr Ke, under whose ‘care’ Yujiro is kept during his time in Taipei – which owing to the circumstances back home has become a life sentence. ‘If there’s anything bothering you, come to talk to me’, Mr Ke tells Yujiro with utter insincerity, ‘You’re like a son to me’. Mr Ke follows his platitudes by commanding Yujiro to kill Weng-Long Shu, a double-dealing member of Mr Ke’s organisation. It’s a thankless task, but Yujiro accepts it. ‘You’re my son’, Mr Ke tells him by way of thanks, ‘You do as I say’. Another man out of place, Yujiro – the protagonist of Rainy Dog – finds himself completely exiled by his brother’s ascension to the role of head of a yakuza clan. Via a telephone call, Yujiro’s brother breaks this news to him, telling Yujiro ‘I’m taking over. So that leaves you with no place to go’. ‘You’ve done for me, brother’, Yujiro reflects in his voiceover, ‘Really done for me [….] What a fucking mess!’ Yujiro is patronised by local gangster Mr Ke, under whose ‘care’ Yujiro is kept during his time in Taipei – which owing to the circumstances back home has become a life sentence. ‘If there’s anything bothering you, come to talk to me’, Mr Ke tells Yujiro with utter insincerity, ‘You’re like a son to me’. Mr Ke follows his platitudes by commanding Yujiro to kill Weng-Long Shu, a double-dealing member of Mr Ke’s organisation. It’s a thankless task, but Yujiro accepts it. ‘You’re my son’, Mr Ke tells him by way of thanks, ‘You do as I say’.

Rainy Dog has strong similarities with a number of other 1990s films in which hitmen, or at least violent criminals, are forced to take care of a child. During that era, the juxtaposition of the connotations of the profession of a violent gangster or hitman and the innocence associated with childhood was exploited in a number of films from a variety of cultural contexts: Clint Eastwood’s A Perfect World (1993) featured Kevin Costner as an escaped convict who kidnaps an eight year old boy and finds himself taking on an almost fatherly role to the child; in Luc Besson’s Leon (1994), Jean Reno’s hitman takes a teenaged girl (Natalie Portman) under his wing and teaches him the tricks of his trade; and in Kitano Takeshi’s Kikujiro (1998, the recent Third Window Films Blu-ray release of which has been reviewed by us here), a middle-aged yakuza (played by Kitano) finds himself escorting a young boy, Masao, across Japan.  As a parent of a child of a similar age to Ah-Chen, at times Rainy Dog is tough to watch owing to Yujiro’s neglect of the boy – and, in fact, the manner in which Ah-Chen’s mother abandons him. The boy’s mother arrives at Yujiro’s home: she apparently had a brief fling with Yujiro which resulted in the birth of Ah-Chen, though Yujiro can barely remember her. She leaves Ah-Chen with Yujiro, telling the gangster ‘I’ve looked after him [the child] so far. Now it’s your turn’. Left alone with the boy, Yujiro reflects in his narration on his status as the child’s father: ‘Who are you?’, he asks, ‘Are you my son? That woman, the one who brought you. I remember, I did fuck her. It was a long time ago. I can’t remember her name’. Ah-Chen follows Yujiro around like a loyal puppy, but Yujiro doesn’t care for the boy at all, even allowing the child to witness Yujiro’s execution of a rival gangster – a murder that takes place also under the gaze of a crying baby, presumably the child of Yujiro’s target. When Yujiro suspends his ‘hit’ owing to torrential rain and spends the night with the prostitute Lily, Ah-Chen waits outside, taking shelter in an alleyway where he spends the night cuddling a stray dog: the lonely dog acts as a metonym for the boy and his isolation – both of them are unloved and abandoned. The shot of Ah-Chen curled up in the alleyway, embracing the dog as if it were a teddy bear, is one of the film’s most resonant images. As a parent of a child of a similar age to Ah-Chen, at times Rainy Dog is tough to watch owing to Yujiro’s neglect of the boy – and, in fact, the manner in which Ah-Chen’s mother abandons him. The boy’s mother arrives at Yujiro’s home: she apparently had a brief fling with Yujiro which resulted in the birth of Ah-Chen, though Yujiro can barely remember her. She leaves Ah-Chen with Yujiro, telling the gangster ‘I’ve looked after him [the child] so far. Now it’s your turn’. Left alone with the boy, Yujiro reflects in his narration on his status as the child’s father: ‘Who are you?’, he asks, ‘Are you my son? That woman, the one who brought you. I remember, I did fuck her. It was a long time ago. I can’t remember her name’. Ah-Chen follows Yujiro around like a loyal puppy, but Yujiro doesn’t care for the boy at all, even allowing the child to witness Yujiro’s execution of a rival gangster – a murder that takes place also under the gaze of a crying baby, presumably the child of Yujiro’s target. When Yujiro suspends his ‘hit’ owing to torrential rain and spends the night with the prostitute Lily, Ah-Chen waits outside, taking shelter in an alleyway where he spends the night cuddling a stray dog: the lonely dog acts as a metonym for the boy and his isolation – both of them are unloved and abandoned. The shot of Ah-Chen curled up in the alleyway, embracing the dog as if it were a teddy bear, is one of the film’s most resonant images.

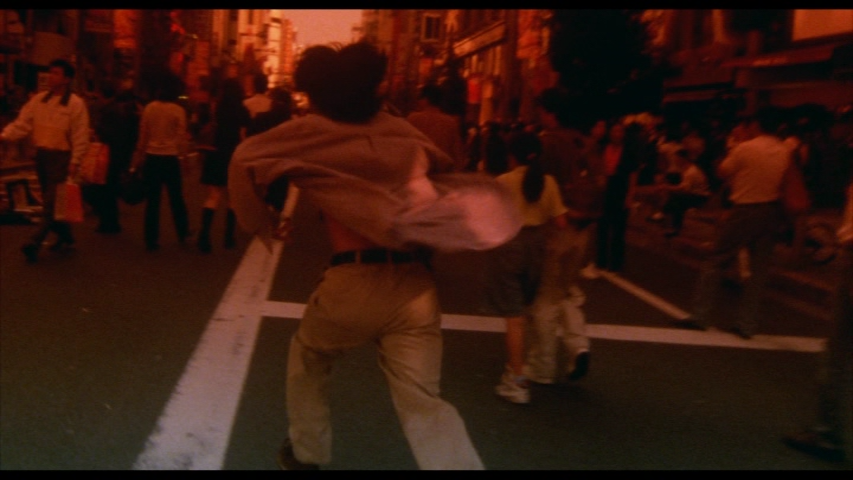

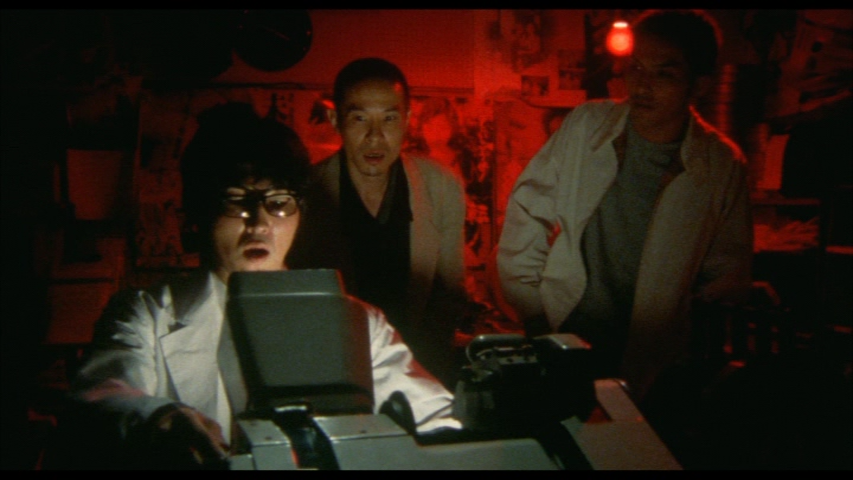

It’s hard to watch Rainy Dog without comparing it with Kitano’s Kikujiro: the two films are strikingly similar, especially in how in their movement towards their respective climaxes they both feature a strong use of a beach location. Where Kikujiro ends on a surprisingly warm note, Rainy Dog features an unremittingly bleak conclusion: both films are heartbreaking in their representation of the relationship between a yakuza and a child, but for very different reasons.  Though thematically similar to the other two films in its focus on matters of displacement and identity, Ley Lines (1999) feels very different owing to its use of tropes of the youth picture and its visual style. In the visual design of this film, Miike abandons the noir-esque chiaroscuro of Shinjuku Triad Society and Rainy Dog, shooting many scenes in bright sunlight and also employing, in a number of sequences, coloured filters of the kind usually used in black-and-white photography: for example, a few times throughout the film, Miike uses a red filter, giving the image a monochromatic bathed-in-red look. The ‘red shift’ is so strong at times that it almost seems like redscale photography (a practice in which the film is exposed in the camera via the opposite surface to the emulsion, resulting in a distinctive red look). Though thematically similar to the other two films in its focus on matters of displacement and identity, Ley Lines (1999) feels very different owing to its use of tropes of the youth picture and its visual style. In the visual design of this film, Miike abandons the noir-esque chiaroscuro of Shinjuku Triad Society and Rainy Dog, shooting many scenes in bright sunlight and also employing, in a number of sequences, coloured filters of the kind usually used in black-and-white photography: for example, a few times throughout the film, Miike uses a red filter, giving the image a monochromatic bathed-in-red look. The ‘red shift’ is so strong at times that it almost seems like redscale photography (a practice in which the film is exposed in the camera via the opposite surface to the emulsion, resulting in a distinctive red look).

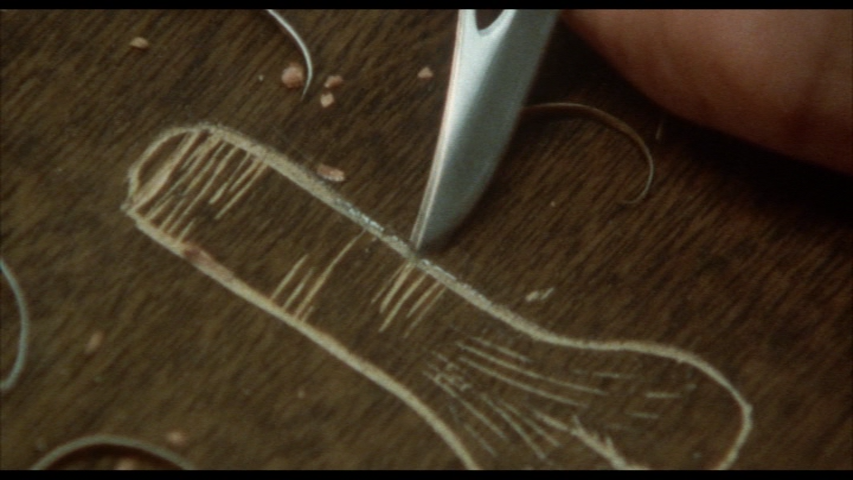

Ryuichi and his brother are introduced as children in the film’s opening sequence. We see the two boys walking on a beach, the footage post-processed to look like an old home movie and therefore carrying connotations of memory and the past. Ryuichi and his brother encounter and are abused by a larger group of children who ridicule the boys’ Chinese heritage (using racial slurs against them) and telling them that they smell. From here, Miike cuts to Ryuichi as a young man; he waits patiently at a counter, where he is told by an official that he cannot apply for a passport whilst he is on probation. Ryuichi is shown in conversation with a series of bureaucrats, who treat him unsympathetically: ‘If you were Japanese, you’d follow Japanese rules’, one of them tells him.  These opening scenes establish the scorn with which Ryuichi and his brother are held owing to their dual heritage. Their unhappiness leads to their desire to flee Japan for a new life in Brazil, and it is this desire which motivates much of the film’s narrative. An energetic and downbeat examination of rootless youth and their dreams of escape, Ley Lines’ scenes depicting the manufacture, bottling and peddling of toluene by Ikeda and his street dealers find some echoes in the recent, acclaimed American television series Breaking Bad (2008-13): the use of protective clothing whilst the material is being bottled, even the heavy focus on a queasy yellow-green palette during these sequences, found its way into Breaking Bad, and it would be interesting to know if the producers of that series were in some way inspired by Ley Lines. The drug itself, toluene, is perhaps best understood as a metonym for the pipe dreams of Ryuichi and his brothers and their desire to escape: ‘Toluene’s made of human happiness’, we are told by one of the characters. In some ways, via its depiction of the single-minded focus of these characters on a pipe dream of happiness which the audience knows is unattainable (and unrealistic, the product of extreme unhappiness), the film has some parallels with the work of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill and the assertion by Larry, in O’Neill’s 1939 play The Iceman Cometh, that ‘The lie of a pipe-dream is what gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober’. The drug (toluene), and the money it produces, represent the potential for this pipe dream to be fulfilled. Meanwhile, the opposite side of this ‘human traffic’ – the reality of it as an economy in human souls – is shown when the prostitute Anita is depicted with one of her sadistic clients, who kicks her and tells her pointedly, ‘Bitch! This is all about the money’. That line, cruel but honest, arguably functions as the film’s epiphany – the realisation that Ryuichi and his crew are faced with when their dream of escape begins to collapse. These opening scenes establish the scorn with which Ryuichi and his brother are held owing to their dual heritage. Their unhappiness leads to their desire to flee Japan for a new life in Brazil, and it is this desire which motivates much of the film’s narrative. An energetic and downbeat examination of rootless youth and their dreams of escape, Ley Lines’ scenes depicting the manufacture, bottling and peddling of toluene by Ikeda and his street dealers find some echoes in the recent, acclaimed American television series Breaking Bad (2008-13): the use of protective clothing whilst the material is being bottled, even the heavy focus on a queasy yellow-green palette during these sequences, found its way into Breaking Bad, and it would be interesting to know if the producers of that series were in some way inspired by Ley Lines. The drug itself, toluene, is perhaps best understood as a metonym for the pipe dreams of Ryuichi and his brothers and their desire to escape: ‘Toluene’s made of human happiness’, we are told by one of the characters. In some ways, via its depiction of the single-minded focus of these characters on a pipe dream of happiness which the audience knows is unattainable (and unrealistic, the product of extreme unhappiness), the film has some parallels with the work of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill and the assertion by Larry, in O’Neill’s 1939 play The Iceman Cometh, that ‘The lie of a pipe-dream is what gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober’. The drug (toluene), and the money it produces, represent the potential for this pipe dream to be fulfilled. Meanwhile, the opposite side of this ‘human traffic’ – the reality of it as an economy in human souls – is shown when the prostitute Anita is depicted with one of her sadistic clients, who kicks her and tells her pointedly, ‘Bitch! This is all about the money’. That line, cruel but honest, arguably functions as the film’s epiphany – the realisation that Ryuichi and his crew are faced with when their dream of escape begins to collapse.

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were only presented with DVD copies of the finished product and did not have access to the Blu-ray discs.  All three films are uncut and very well-presented here. The three films are all presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio (which by all accounts is the intended ratio for these films), with anamorphic enhancement on the DVDs. The image is clear and detailed, and contrast levels are good: the film noir-esque low light photography in Shinjuku Triad Society is represented very well, with strong midtones and good gradation to the blacks – even on the DVDs which were provided for review. The lighting in Rainy Dog is more naturalistic than its predecessor, and this is carried well within the film. It’s worth noting that Rainy Dog features one curious instance of a stuttering effect in one scene which was a result of Miike asking his camera operator to experiment with film speeds in the manner of Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express (1993) or Fallen Angels (1995). (This is addressed in Tom Mes’ commentary for Rainy Dog; and because it’s such an isolated and jarring example of such a technique, first time viewers would be forgiven for perhaps thinking that there is a problem with the presentation – but rest assured that it’s certainly an intentional experimentation with camera technique.) Some of the compositions within Rainy Dog feel very tight along the vertical axis, with the tops of heads often disappearing out of the frame – but this may very well be a product of Miike’s ‘fast’ technique. (I’d long since misplaced the Tartan DVD release of that film, which was the only DVD release of Rainy Dog I’d previously owned, so it’s impossible for me to compare the framing here with the framing of that release.) All three films are uncut and very well-presented here. The three films are all presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio (which by all accounts is the intended ratio for these films), with anamorphic enhancement on the DVDs. The image is clear and detailed, and contrast levels are good: the film noir-esque low light photography in Shinjuku Triad Society is represented very well, with strong midtones and good gradation to the blacks – even on the DVDs which were provided for review. The lighting in Rainy Dog is more naturalistic than its predecessor, and this is carried well within the film. It’s worth noting that Rainy Dog features one curious instance of a stuttering effect in one scene which was a result of Miike asking his camera operator to experiment with film speeds in the manner of Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express (1993) or Fallen Angels (1995). (This is addressed in Tom Mes’ commentary for Rainy Dog; and because it’s such an isolated and jarring example of such a technique, first time viewers would be forgiven for perhaps thinking that there is a problem with the presentation – but rest assured that it’s certainly an intentional experimentation with camera technique.) Some of the compositions within Rainy Dog feel very tight along the vertical axis, with the tops of heads often disappearing out of the frame – but this may very well be a product of Miike’s ‘fast’ technique. (I’d long since misplaced the Tartan DVD release of that film, which was the only DVD release of Rainy Dog I’d previously owned, so it’s impossible for me to compare the framing here with the framing of that release.)

Colour reproduction is solid throughout. This is particularly noticeable in Ley Lines, which features some very bold use in colour seemingly achieved by the use of monochrome filters on the lens (eg, a high contrast red filter, in at least one scene in the film). Ley Lines features the most outrageously experimental photography out of all three films, shucking off the chiaroscuro photography of its predecessors in favour of a very stylised aesthetic – which includes, in one sequence, a shot presented as if the camera were positioned inside the blades of a speculum that has been inserted into a woman’s vagina(!) Shinjuku Triad Society and, in particular, Ley Lines also pokes fun at Japanese trend in optical censorship by featuring a number of scenes in which characters expose their genitals – only for the characters’ genitals to be censored in a very overt, parodic manner. Please see the bottom of this review for some larger screengrabs from each film.

Audio

All three films feature a mix of languages, principally Japanese and a number of Chinese dialects (with a spattering of English dialogue here and there). On the DVDs, the films are presented with Dolby Digital 2.0 tracks. Ley Lines again pokes fun at trends in censorship on its audio track: taboo words are prominently bleeped out. All three films feature a mix of languages, principally Japanese and a number of Chinese dialects (with a spattering of English dialogue here and there). On the DVDs, the films are presented with Dolby Digital 2.0 tracks. Ley Lines again pokes fun at trends in censorship on its audio track: taboo words are prominently bleeped out.

Optional English subtitles are provided for all three films. These subtitles improve greatly on those that were included in Tartan’s DVD releases of these films. For example, in the case of Shinjuku Triad Society Arrow’s subtitles translate the final lines of the film in a manner which seems to be much more correct (and makes much more sense) than the translation that was included in Tartan’s DVD release of that film, and in the case of Rainy Dog much of the Chinese dialogue that was strangely unsubtitled in Tartan’s release now, on Arrow’s new discs, features English subtitles.

Extras

All three films feature commentaries by Tom Mes. These commentaries are absolutely superb, featuring indepth analysis of the films with information about their production and their relationships with Miike’s other films. All three films feature commentaries by Tom Mes. These commentaries are absolutely superb, featuring indepth analysis of the films with information about their production and their relationships with Miike’s other films.

The other content of the DVDs are as follows: DISC ONE: * Shinjuku Triad Society (101:17 PAL) - Audio commentary with Tom Mes. - ‘Takashi Miike: Into the Black’ (45:07). This lengthy new interview with Miike Takashi sees the director talking about his relationship with cinema, beginning with his fascination with Bruce Lee’s films. He reflects on the training he received early in his career. He says that ‘As a kid, the only thing I was good at was running away. And I’ve been running away ever since. But, in the midst of running away, I became a director’. Miike goes on to discuss his early career in V-Cinema and how he developed his approach as a director. The interview is in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Trailer (1:25). DISC TWO: * Rainy Dog (94:24 PAL) - Audio commentary with Tom Mes. - ‘Show Aikawa: Stray Dog, Lone Wolf’ (21:42). In a new interview, the actor talks about his work in V-Cinema and the films he made with Miike. Like the Miike interview, this is in Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Trailer (1:26). DISC THREE: * Ley Lines (104:36 PAL) - Audio commentary with Tom Mes. - Trailer (1:40).

Overall

These are energetic and nihilistic films. A recurring theme, aside from the theme of displacement and outsider-ship, is the corruption of youth – or rather the collision of youthful idealism and innocence with the cruelty of the adult world. As the films progress, this theme becomes more pronounced – in Yujiro’s relationship with Ah-Chen, for example, and particularly in the events that Ryuichi and his brother become a part of in Ley Lines. These are energetic and nihilistic films. A recurring theme, aside from the theme of displacement and outsider-ship, is the corruption of youth – or rather the collision of youthful idealism and innocence with the cruelty of the adult world. As the films progress, this theme becomes more pronounced – in Yujiro’s relationship with Ah-Chen, for example, and particularly in the events that Ryuichi and his brother become a part of in Ley Lines.

The three films are linked by a very film noir-style approach. Figures of authority are invariably represented as corrupt or powerless. Isolde Standish has declared that in Shinjuku Triad Society, for example, the police are represented ‘as mediators who maintain stability between the two mutually dependent financial concerns of “legitimate” society and those of the underground represented by the triad/yakuza organisations’ (Standish, 2006: 335). The films represent an escalation of Miike’s style, and each film in the trilogy sees Miike becoming bolder in terms of his technique; Jasper Sharp has said that the three films in the kuroshakai trilogy ‘consolidated his [Miike’s] association with the yakuza genre, while containing interesting observations about Asian ethnic minorities in Japan’ (Sharp, 2011: 161). These are concerns which would run throughout Miike’s subsequent films, in the Dead or Alive pictures, for example, or such films as The City of Lost Souls (2000). The three films here offer an excellent experience, for both Miike fans and for the uninitiated. We were only given the DVDs for review purposes, but these offer vast improvements over the previously available DVDs – if only for the more accurate and consistent subtitling of the first two pictures. Furthermore, Arrow’s new release of the ‘Black Society Trilogy’ includes some superb contextual material: Tom Mes’ commentary tracks for all three films are a delight, and the new interview with Miike is detailed, heartfelt and fascinating. References: Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris Magee, Chris, 2011: World Film Locations: Tokyo. Intellect Books Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Scarecrow Press Standish, Isolde, 2006: A New History of Japanese Cinema. Bloomsbury Publishing Shinjuku Triad Society:

Rainy Dog:

Ley Lines:

|

|||||

|