|

|

The Film

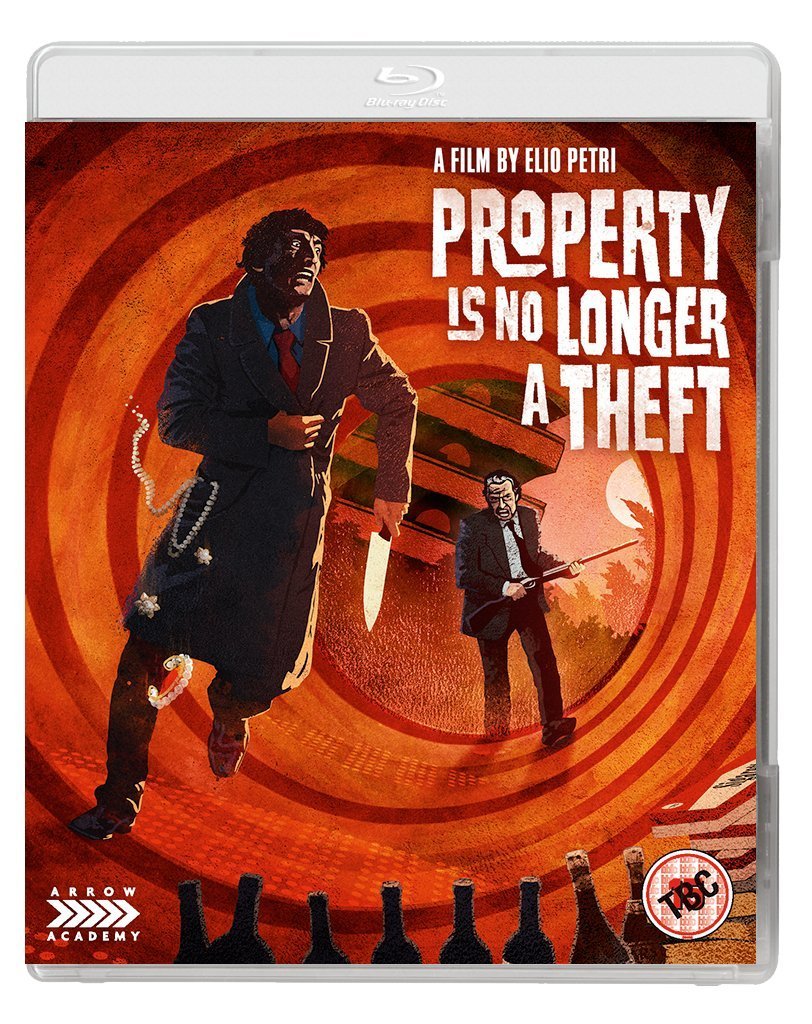

Property Is No Longer a Theft (Elio Petri, 1973) Property Is No Longer a Theft (Elio Petri, 1973)

Profoundly allergic to money, Total (Flavio Bucci) is employed at a bank, like his now retired father (Salvo Randone) before him. During his working hours at the bank, Total sees and is repulsed by one of the bank’s clients, a wealthy butcher (Ugo Tognazzi). Total becomes envious of the butcher’s wealth and resentful of his own position in life – one of poverty. Where the butcher 'has' in abundance, Total and his fathers 'have not'. One day, a group of armed robbers hold the bank's employees and customers at gunpoint, until the bank’s attack dogs are released. All but one of the robbers escapes; the remaining robber is injured by the dogs and lies in pain on the ground. The butcher, who has visited the bank to ask for yet another loan, steps over to the injured man and kicks him viciously. Total approaches the bank manager and asks for a loan over and above what he is entitled to, and when this plea is rejected, Total decides to target the butcher – out of envy, and out of a sense of remedying the inequalities that exist between their two positions in life. He visits one of the butcher’s shops, where the butcher is engaged in an argument with one of his customers over his dishonest practices ('fixing' the scales and selling underweight cuts of meat); and whilst the butcher’s attention is otherwise diverted, Total steals the butcher’s knife. Later, at a cinema showing a pornographic film, Total sits behind the butcher whilst the butcher has his lover and employee Anita (Daria Nicolodi) perform fellatio on him. Total takes this opportunity to steal the butcher’s hat. Wearing the butcher’s hat, a stocking over his face, and carrying the stolen knife, Total gains entry into the butcher’s home and terrorises Anita. After Total flees, the butcher seizes the opportunity to pack into a suitcase many of his valuables, then claims to the police that the intruder (Total) stole items worth over forty million lire. The butcher reminds Anita that it is not in his interest for the intruder to be caught by the police, as this may lead to the revelation that the butcher has committed insurance fraud and may also lead to an investigation into the dishonest practices on which the butcher’s business empire has been founded: his secret slaughterhouse would be closed down, and he would also be investigated over the fact that a number of his employees don’t pay tax.  However, the butcher is infuriated when Total continues to target him. In a monologue, Anita explains to the audience her position as yet another of the butcher's possessions, there to service him sexually; this relationship, of the butcher counting Anita amongst the items he owns, leads to Total 'stealing' Anita and bringing her home to the flat in which he lives with his father. Anita offers herself sexually to Total, but Total reacts by humiliating her. However, the butcher is infuriated when Total continues to target him. In a monologue, Anita explains to the audience her position as yet another of the butcher's possessions, there to service him sexually; this relationship, of the butcher counting Anita amongst the items he owns, leads to Total 'stealing' Anita and bringing her home to the flat in which he lives with his father. Anita offers herself sexually to Total, but Total reacts by humiliating her.

The butcher is also pestered by the brigadier (Orazio Orlando) who has taken charge of the investigation into the theft. The brigadier wishes to capture the alleged thief, but of course the butcher wishes for the thief to avoid the law. As a result, the butcher approaches Total and attempts to come to an agreement with him which will ensure that the butcher's nefarious business practices, and his falsification of the report of the objects 'stolen' from his home, never come to light. Meanwhile, Total begins an association with an actor and professional burglar, Albertone (Mario Scaccia), with the aim of enlisting Albertone's help in targeting the butcher. Director Elio Petri began as a journalist and film critic for L'Unità, the official newspaper of the Italian Communist Party that was founded by Antonio Gramsci in the 1920s. Following the violence that erupted in Hungary in 1956, Petri became alienated from the Communist Party, but an articulation of leftist politics continued to dominate his career within cinema. In the 1950s, Petri turned from the world of film criticism to writing scripts for films and making documentaries before being presented with the opportunity to direct his first narrative feature, L’assassino (1961). Via some superb monochrome photography and a potent performance by Marcello Mastroianni in the lead role of a sleazy playboy who is accused of the murder of his lover, L’assassino offered a keen sense of social commentary that would characterise Petri’s subsequent pictures.  From the outset, Petri’s films as a director evidenced a sly, satirical eye and a keen focus on issues of social class and inequality. With Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto (Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, 1970), arguably his most famous film outside Italy, this sense of social criticism became even more overt and aggressive, and with that picture Petri began a series of films that used almost Brechtian cinematic techniques to distance the viewer from the narrative, and which preoccupied themselves with communicating a profound sense of distrust in figures of authority and the status quo. In this sense, Petri’s films may be considered examples of agitprop art not unlike the theatre of, say, Caryl Churchill. Neglected in much English-language criticism of Petri’s work, probably because it is so little seen outside Italy, is Petri’s subsequent piece, ‘Tre ipotesi sulla morte di Giuseppe Pinelli’ (‘Three Hypotheses on the Death of Giuseppe Pinelli’, 1970), made with Gian Maria Volonte (the star of Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion who was known for his outspoken leftist politics) and focusing on the death of the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli. Pinelli was arrested following the Piazza Fontana bombing in 1969, and he fell to his death from the fourth floor of a police station in Milan. The police’s statements regarding Pinelli’s death were contradictory, and in response to questions raised about the incident, in 1971 the commissioner (Luigi Calabresi) and two other officers were placed under investigation; however, Pinelli’s death was later ruled to be the result of an ‘accident’. From the outset, Petri’s films as a director evidenced a sly, satirical eye and a keen focus on issues of social class and inequality. With Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto (Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, 1970), arguably his most famous film outside Italy, this sense of social criticism became even more overt and aggressive, and with that picture Petri began a series of films that used almost Brechtian cinematic techniques to distance the viewer from the narrative, and which preoccupied themselves with communicating a profound sense of distrust in figures of authority and the status quo. In this sense, Petri’s films may be considered examples of agitprop art not unlike the theatre of, say, Caryl Churchill. Neglected in much English-language criticism of Petri’s work, probably because it is so little seen outside Italy, is Petri’s subsequent piece, ‘Tre ipotesi sulla morte di Giuseppe Pinelli’ (‘Three Hypotheses on the Death of Giuseppe Pinelli’, 1970), made with Gian Maria Volonte (the star of Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion who was known for his outspoken leftist politics) and focusing on the death of the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli. Pinelli was arrested following the Piazza Fontana bombing in 1969, and he fell to his death from the fourth floor of a police station in Milan. The police’s statements regarding Pinelli’s death were contradictory, and in response to questions raised about the incident, in 1971 the commissioner (Luigi Calabresi) and two other officers were placed under investigation; however, Pinelli’s death was later ruled to be the result of an ‘accident’.

The incident helped to deepen the rifts that already existed within Italian society, inspiring much comment in the world of music, cinema and theatre – including Dario Fo’s highly-regarded 1970 play Morte accidentale di un anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist). The death of Pinelli also seems to have been a watershed moment in Petri’s career, driving him to make films which were increasingly critical of the establishment and unafraid of challenging the dominant paradigms of fiction filmmaking, utilising strongly Brechtian techniques in their construction. Where Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion – a film which focuses on a police inspector (Gian Maria Volonte) who murders his mistress (Florinda Bolkan) and challenges his colleagues to arrest him – had channelled something of the zeitgeist surrounding Pinelli’s death, ‘Three Hypotheses on the Death of Giuseppe Pinelli’ confronted these themes and issues even more directly, in a narrative based directly on the case itself. Offering an ironic interpretation of the two different versions of Pinelli’s death that were recorded in official police reports of the incident (one of which suggested that Pinelli committed suicide), and contrasting these with the hypothetical scenario put forward by the Left (in which Pinelli was alleged to have been tortured before being thrown out of the window), Petri’s film was made to be screen at political gatherings (Foot, 2007: 62). The picture makes use of Brechtian techniques, opening on the clapperboard used to announce the beginning of a shot, and employing a documentary aesthetic, employing techniques honed in Petri's early work within that genre, to give the illusion that what we are seeing unfold on the screen is spontaneous. The actors don’t dress in costume, with Volonte dressed extremely casually, in jeans and carrying a microphone; he addresses the camera directly, often gazing at it in an almost confrontational and even combative manner. The three versions of what might have happened to Pinelli in the police station are played out, Volonte interviewing the men who enact these hypotheses about their perceived legitimacy and behaving like a reporter questioning the events as they unfold. Genuine anger boils beneath Volonte's questions and monologues. The performers sweat, a palpable sense of intense pressure filling every frame. The combination of techniques associated with drama and documentary forms might remind the viewer of Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1965) or Culloden (1964). In the words of John Foot, ‘[t]he effect is gripping—as if the film is being created before our eyes’ (Foot, op cit.: 62). John Foot argues that Petri’s film shows ‘a clear debt to Brechtian theatre, communicating the political message without using props’ (ibid.). Foot argues that as leftist cinema (along with other aspects of Italian cultural life) became increasingly radical following Pinelli’s death, filmmakers like Petri ‘wanted to break down the “fourth wall” between the audience and performers. This film [‘Three Hypotheses….’] is an example of this kind of work applied to the cinematic form’ (ibid.). Watching the film, clearly intended to arouse anger and agitation at the venues (mostly leftist political meetings) at which it was intended to be shown, is an intense, provocative experience.  The cultural wound that the death of Pinelli opened within the public eye exposed the notion that the state was ‘willing to murder its citizens and then lie about it’ (Foot, op cit.: 63). This premise, already explored subtly within Petri’s cinema, became the driving focus for much of Petri’s later film work; the director’s subsequent films become obsessive in their exploration of how power and authority may be abused to ‘erase’ the exploitation of the powerless within society. Certainly, these themes were explored with a great deal of clarity in Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, even though the picture was released a mere two months after the Piazza Fontana bombing and had been written and produced prior to this event: Roberto Curti argues that Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion ‘conveyed the mood of the period with an almost shocking precision within a crime story sui generis’ (Curti, 2013: 40). The cultural wound that the death of Pinelli opened within the public eye exposed the notion that the state was ‘willing to murder its citizens and then lie about it’ (Foot, op cit.: 63). This premise, already explored subtly within Petri’s cinema, became the driving focus for much of Petri’s later film work; the director’s subsequent films become obsessive in their exploration of how power and authority may be abused to ‘erase’ the exploitation of the powerless within society. Certainly, these themes were explored with a great deal of clarity in Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, even though the picture was released a mere two months after the Piazza Fontana bombing and had been written and produced prior to this event: Roberto Curti argues that Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion ‘conveyed the mood of the period with an almost shocking precision within a crime story sui generis’ (Curti, 2013: 40).

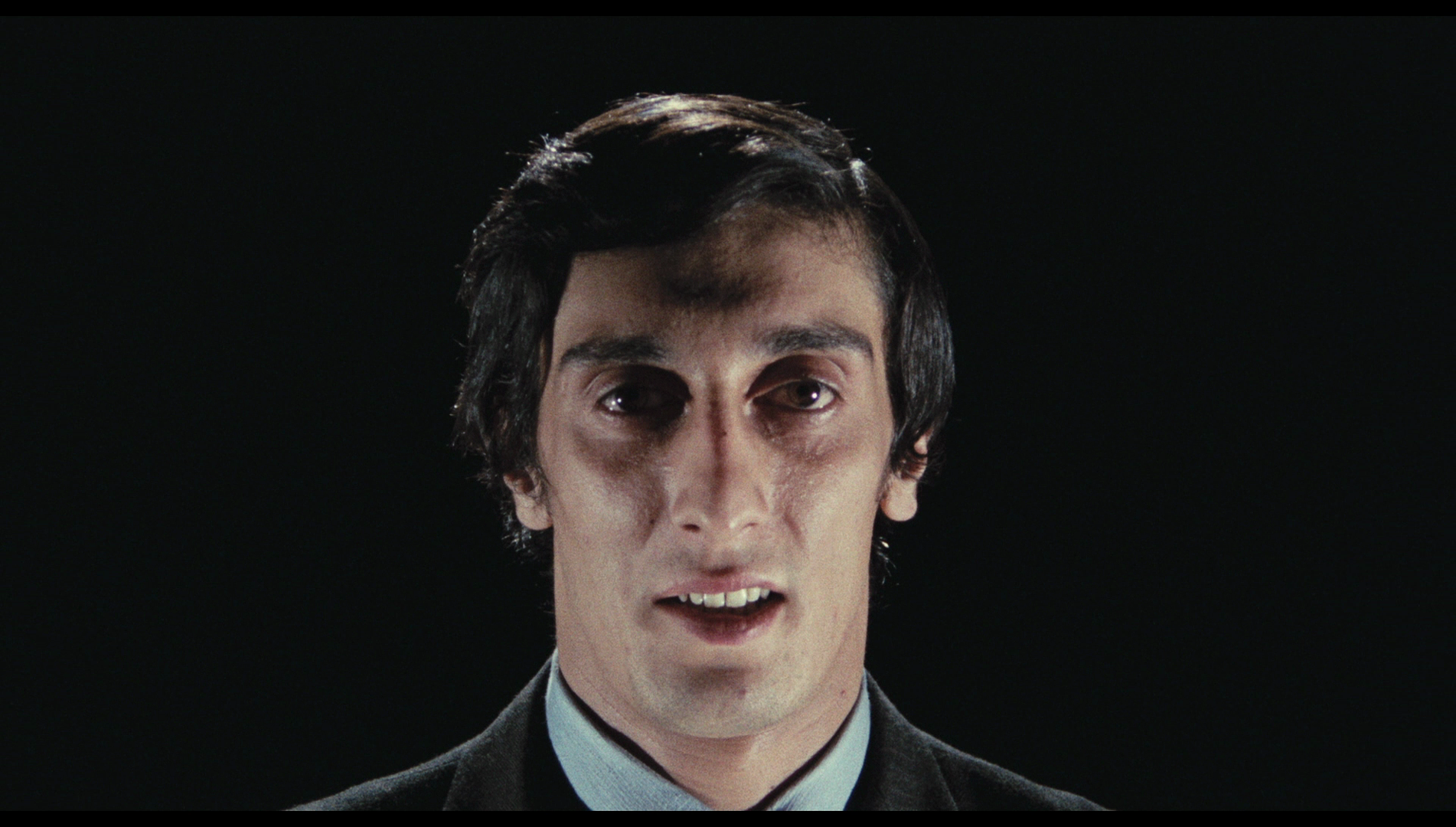

Made several years later, Petri’s La proprietà non è più un furto (Property is No Longer Theft; or, as it's translated on Arrow's release, Property is No Longer a Theft) opens with a similar sensibility in place. The film begins with the protagonist, Total, narrating. He is placed in close-up, gazing directly at the camera – at the audience – and framed against empty black space, as if on a stage. During this opening narration, Total outlines his worldview explicitly, addressing the film's viewers: ‘I, Mr Total, the accountant, am no different from you, and you are no different from me. We are equal in our needs and unequal in the way we satisfy them. I know that I’ll never be able to have any more than I have now, until the day I die, but none of you will be able to have more than you have now either [….] And in the struggle, whether legal or illegal, to obtain what we don’t have, many people fall ill with shameful diseases. Their bodies fill up with sores, inside and out. Many others fall down dead. They are excluded, destroyed, transformed. They become beasts, stones, dead trees, worms. That’s how envy is born, and in this envy class hatred is hidden. It’s born out of egoism, which makes it innocuous. Egoism is the fundamental sentiment of the religion of property’. Total finishes his monologue by implicating the audience directly in his worldview: ‘I feel that this condition is becoming intolerable, and I know many of you feel the same way’.  As the narrative progresses, the other principal characters in the film address the audience in a similar manner, the Brechtian dismantling of the ‘fourth wall’ becoming increasingly aggressive. Against a similar abstract background, the butcher is shown reflecting on his wealth and his dissatisfaction with what he has got: ‘What will I do with all this money I’ve accumulated, now that I’m in a position, as I have been for some time, to take care of all the needs I have in life?’, the butcher asks, ‘Well, I’ll use it to make even more [….] Because my fundamental need is to get richer’. The brigadier, in his monologue, expresses the frustrations of the petty bureaucrat which, he asserts, find release in the victimisation of criminals (or those perceived to be criminals): he suggests his endeavours are often for nought, and that 'legitimate' society defines itself against (and therefore needs) thieves and criminals – and consequently, the brigadier and his colleagues are like Sisyphus with his rock - 'And so I'm consumed with pessimism and console myself with the egotistical nature of my privileges. First and foremost, the freedom to arrest anyone that I want. Arresting people is a wonderful thing', he says. As the narrative progresses, the other principal characters in the film address the audience in a similar manner, the Brechtian dismantling of the ‘fourth wall’ becoming increasingly aggressive. Against a similar abstract background, the butcher is shown reflecting on his wealth and his dissatisfaction with what he has got: ‘What will I do with all this money I’ve accumulated, now that I’m in a position, as I have been for some time, to take care of all the needs I have in life?’, the butcher asks, ‘Well, I’ll use it to make even more [….] Because my fundamental need is to get richer’. The brigadier, in his monologue, expresses the frustrations of the petty bureaucrat which, he asserts, find release in the victimisation of criminals (or those perceived to be criminals): he suggests his endeavours are often for nought, and that 'legitimate' society defines itself against (and therefore needs) thieves and criminals – and consequently, the brigadier and his colleagues are like Sisyphus with his rock - 'And so I'm consumed with pessimism and console myself with the egotistical nature of my privileges. First and foremost, the freedom to arrest anyone that I want. Arresting people is a wonderful thing', he says.

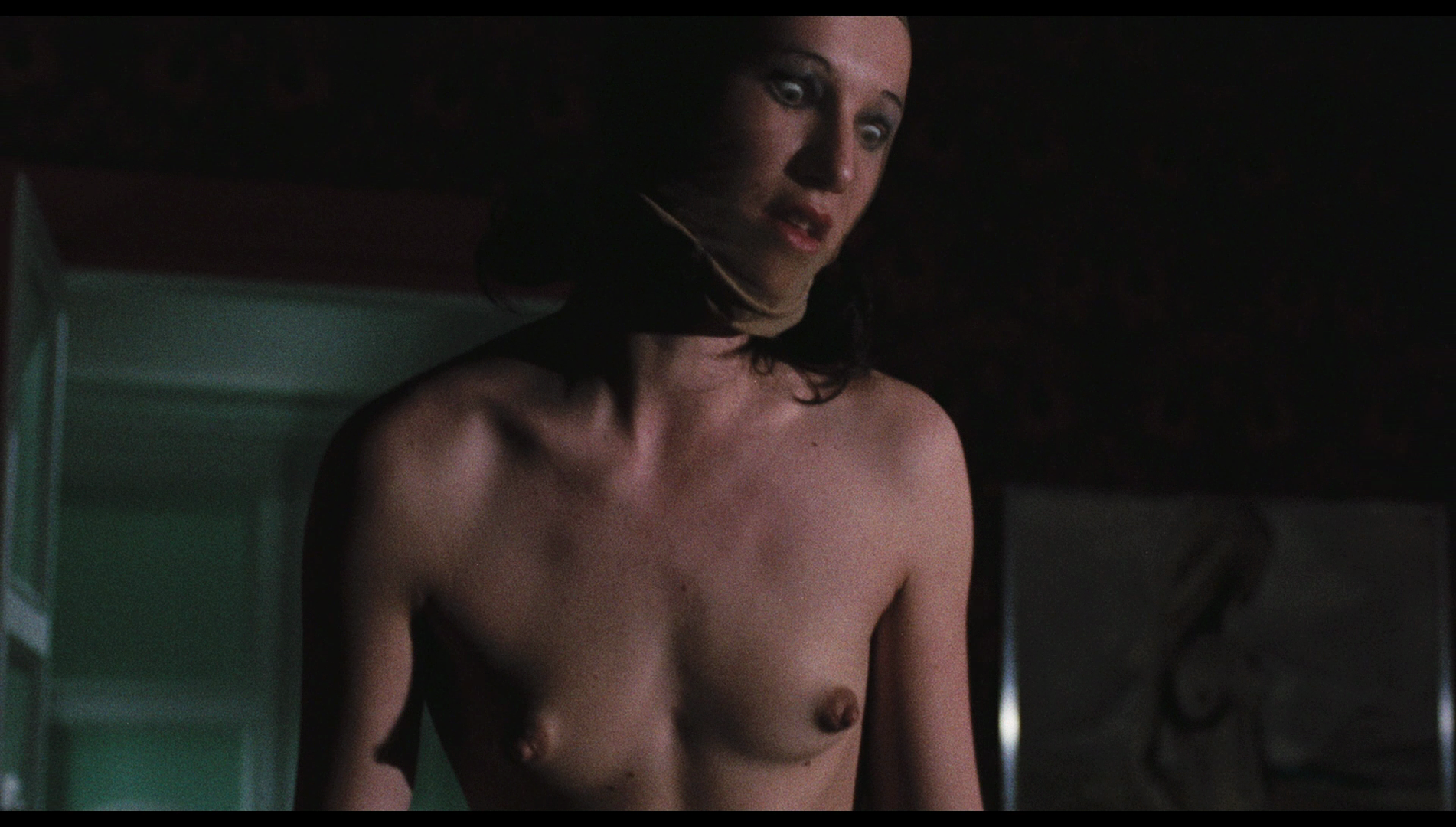

When it comes to Anita’s turn to deliver her monologue, she implicates the audience even more directly. ‘I feel like a thing. I’ve become a thing’, Anita says, reflecting on the extent to which she has become simply another of the butcher’s possessions. ‘I am many pieces, many pieces of a thing [….] They always open me up, like a can of tomatoes, with their dick – or without it, their fingers’, she continues, suggesting her role has come to be to ‘service’ sexually those who ‘possess’ her. (Later, she will tell Total, ‘Sometimes I become like a worker, and he [the butcher] is like a machine I have to operate [….] I clock in, and he "gets some"’.) ‘If I weren’t here, I’d be somewhere else […], at the cinema, like you’, Anita says, her appeal of similarity to the film’s audience offering a classic example of Brechtian distanciation that reminds the film’s viewers of the picture’s status as a construct. Anita’s status as a ‘possession’ is reinforced when Total ‘steals’ her from the butcher’s shop, returning with Anita to the flat he shares with his father. Total tells his father that he ‘stole’ Anita from the butcher. Anita confirms that this is true: ‘I belong in a butcher’s shop. He took me from the shop window’, she says.  Riddled with grotesquerie and caricature, Petri's film establishes a relationship between wealth and sexual deviance. Where Total is repressed, the butcher relishes in his various peccadilloes. The butcher surrounds himself with pornographic artworks; and Total, who has followed the butcher into a cinema showing a pornographic film, lurks on the sidelines as the butcher has his mistress Anita fellate him in the auditorium. (This offers Total the opportunity to steal the butcher’s hat.) Later, after Total has broken into the butcher’s home and terrorised Anita, the butcher has Anita fuck him whilst wearing a stocking over her face, distorting her features, and shouting ‘Stop, thief!’ (It’s a scene that was deeply controversial in Italy upon the film’s first release.) Riddled with grotesquerie and caricature, Petri's film establishes a relationship between wealth and sexual deviance. Where Total is repressed, the butcher relishes in his various peccadilloes. The butcher surrounds himself with pornographic artworks; and Total, who has followed the butcher into a cinema showing a pornographic film, lurks on the sidelines as the butcher has his mistress Anita fellate him in the auditorium. (This offers Total the opportunity to steal the butcher’s hat.) Later, after Total has broken into the butcher’s home and terrorised Anita, the butcher has Anita fuck him whilst wearing a stocking over her face, distorting her features, and shouting ‘Stop, thief!’ (It’s a scene that was deeply controversial in Italy upon the film’s first release.)

The texture of greed permeates throughout Petri’s picture, from its opening titles sequence featuring atonal sounds and gasping voices conjugating the verb ‘to have’ (‘I have… You have.. He has… They have’). The film’s title, of course, alludes to the slogan (‘Property is theft!’) coined by French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book What is Property? (1840). The film returns time and time again to the concept of property as a signifier of social standing. The story begins in the bank by which Total is employed and in which he encounters the butcher. The bank is filled with Renaissance artwork, its ceiling painted with a fresco and the Eye of Providence adorning the walls and glass panels in the doors. Everything within the mise-en-scène suggests a bloated sense of wealth, the building offering a strange mixture of the iconography of a church or place of culture and the tables of the moneylenders who pollute the Temple in Jerusalem (turning it into a ‘den of thieves’) in the Book of Matthew. Into this scenario wanders the butcher; Total watches as the butcher greases the palms of the bank’s senior employees with free gifts of meat, before extracting large sums of money from them. (At the end of the film, the butcher attempts to buy the silence of Total and his father with similar gifts of meat.) When a group of armed robbers attempt to steal from the bank, they are set upon by the bank’s guard dogs. One of the robbers, wounded by a dog, writhes on the floor in agony. The butcher strides over to this injured man and kicks him cruelly. ‘Let me vent my anger before they take him away’, complains the butcher.  Total’s plan to target the butcher is set in place almost immediately, and is legitimised for the audience when we see Total ‘casing’ the butcher’s shop, with its marble walls bearing a mural which reads ‘MAN IS A CARNIVOROUS ANIMAL’. The connection between symbols of wealth and the devouring of flesh is made in an overt manner, the butcher lording over his customers, elevated on a platform and sharpening his knives over a joint of meat. A woman complains that the butcher is ‘fixing’ the scales he uses to weight the meat, overcharging his customers. Whilst the butcher’s attention is diverted, Total steals the butcher’s knife; noticing the knife has gone missing, the butcher complains ‘There’s a thief among us’. ‘Yes’, one of the female customers says, ‘Call the cops. Then we can talk about prices and weight too’. Total’s plan to target the butcher is set in place almost immediately, and is legitimised for the audience when we see Total ‘casing’ the butcher’s shop, with its marble walls bearing a mural which reads ‘MAN IS A CARNIVOROUS ANIMAL’. The connection between symbols of wealth and the devouring of flesh is made in an overt manner, the butcher lording over his customers, elevated on a platform and sharpening his knives over a joint of meat. A woman complains that the butcher is ‘fixing’ the scales he uses to weight the meat, overcharging his customers. Whilst the butcher’s attention is diverted, Total steals the butcher’s knife; noticing the knife has gone missing, the butcher complains ‘There’s a thief among us’. ‘Yes’, one of the female customers says, ‘Call the cops. Then we can talk about prices and weight too’.

Total’s acts of theft, and his ‘Mandrakian Marxism’, are contrasted within the film to the butcher’s dishonest practices. ‘Why is it my fault if I’m smarter than them, if I know how to make money?’, the butcher complains to Anita after Total has begun to target him. The butcher is shown ‘fixing’ the scales in his shop, overcharging his customers, and later the butcher reminds Anita that it is not in his interests for the intruder to his home [Total] to be caught by the police, as this would lead to an investigation into the butcher’s act of insurance fraud, his operation of a secret, unlicensed slaughterhouse, his employment of workers who don’t pay tax. ‘It wouldn’t do me any good’, the butcher says in response to that Total may be caught. After Total has acquired entry to the butcher’s home and terrorised Anita, the butcher calls the police. The butcher lies about the incident in his home, telling the police and the insurance company that the intruder stole works of art and jewellery worth over forty million lire. ‘It’d take me over twenty years to earn that’, the brigadier tasked with investigating the theft observes. ‘Yes, but you’re lucky enough to have a fixed salary’, the butcher responds. Later, the butcher and the brigadier come to loggerheads when the brigadier deduces that the butcher is being deliberately uncooperative. The brigadier reminds the butcher of the role of the police within society: 'Look, wise guy', the brigadier says with barely concealed anger, 'Without us theft is no longer theft. It becomes a right, the law, and thieves become revolutionaries'.  Throughout the film, the butcher is concerned with what he owns – his businesses, his collection of (largely pornographic) artworks, his gold and silverware, and even his mistress (Anita). Proudhon’s slogan has attracted all sorts of criticism, including from likeminded thinkers: for example, Max Stimer’s critique of Proudhon’s assertion, put forwards in Stimer’s 1844 book The Ego and Its Own, argues that the concept of ‘theft’ only makes sense if one works from the premise that ‘property’ is a legitimate concept. Ultimately, Petri’s film seems to suggest that ‘theft’ gives legitimacy to the concept of ‘property’. ‘If you’re not afraid of having it stolen, you can’t enjoy your wealth’, the brigadier suggests to the butcher at one point in the film. Through Total’s endeavours, the butcher even begins to question his own morality: ‘I’ve made too much money’, the butcher tells Total towards the end of the film, ‘And not always honestly, I admit it. I’d be willing in spirit to give away everything I have. But I’m not brave enough to be the first to do it [….] I’m afraid of being poor in a world that’s unfortunately dominated by the rich’. In order to effect any true change and bring about a sense of equality, the butcher argues, Total would have ‘to destroy the land registry, kill all the notaries, burn down the police stations, occupy Parliament, take over all the television networks’. Coming in the midst of the anni di piombo/‘Years of Lead’, with Italian society rocked by acts of politically-motivated violence from both the Left and the Right, this statement has incendiary potential: Petri lets the butcher’s assertion hang in the air, Total’s silence seeming almost like a validation of the suggestion that, yes, performing these acts of revolution and rebellion might very well bring about a more fair, equal society. The dialogue ends in Total wrestling with the butcher, Flavio Bucci’s wiry physique seeming to be absorbed by the barrel chested Ugo Tognazzi. ‘I’ll never accept! Never! Exploiter! Bloodsucker!’, Total cries. ‘I’m strong’, the butcher responds simply. Throughout the film, the butcher is concerned with what he owns – his businesses, his collection of (largely pornographic) artworks, his gold and silverware, and even his mistress (Anita). Proudhon’s slogan has attracted all sorts of criticism, including from likeminded thinkers: for example, Max Stimer’s critique of Proudhon’s assertion, put forwards in Stimer’s 1844 book The Ego and Its Own, argues that the concept of ‘theft’ only makes sense if one works from the premise that ‘property’ is a legitimate concept. Ultimately, Petri’s film seems to suggest that ‘theft’ gives legitimacy to the concept of ‘property’. ‘If you’re not afraid of having it stolen, you can’t enjoy your wealth’, the brigadier suggests to the butcher at one point in the film. Through Total’s endeavours, the butcher even begins to question his own morality: ‘I’ve made too much money’, the butcher tells Total towards the end of the film, ‘And not always honestly, I admit it. I’d be willing in spirit to give away everything I have. But I’m not brave enough to be the first to do it [….] I’m afraid of being poor in a world that’s unfortunately dominated by the rich’. In order to effect any true change and bring about a sense of equality, the butcher argues, Total would have ‘to destroy the land registry, kill all the notaries, burn down the police stations, occupy Parliament, take over all the television networks’. Coming in the midst of the anni di piombo/‘Years of Lead’, with Italian society rocked by acts of politically-motivated violence from both the Left and the Right, this statement has incendiary potential: Petri lets the butcher’s assertion hang in the air, Total’s silence seeming almost like a validation of the suggestion that, yes, performing these acts of revolution and rebellion might very well bring about a more fair, equal society. The dialogue ends in Total wrestling with the butcher, Flavio Bucci’s wiry physique seeming to be absorbed by the barrel chested Ugo Tognazzi. ‘I’ll never accept! Never! Exploiter! Bloodsucker!’, Total cries. ‘I’m strong’, the butcher responds simply.

Total’s allergic response to the presence of money is signalled in the film’s opening sequence, Total scratching nervously at his hands and his neck whilst performing his duties at the bank. He refuses to handle cash without wearing his gloves. He enters the bank’s vault and carries money to one of the tellers. A colleague addresses Total, commenting on the gloves that Total insists on wearing: ‘Money’s clean’, Total’s colleague says, ‘It doesn’t stink. But if it’s dirty, you get dirty too’. Returning to the dingy flat in which he lives with his father, Total engages his parent in a dialectical conversation about the nature of money. Total’s father resorts to sententia, enacting the habit of acquired discourse (rather than reason or logic) to reinforce his insistence that the concept of property is paramount – rather like one of the brainwashed denizens of George Orwell’s 1984. ‘Have you ever stolen anything?’, Total asks his father. ‘Never’, his father responds, ‘“Property is sacred”’. ‘“The mother is always known”, Total asserts, mocking his father’s aphoristic response, ‘“I came, I saw, I conquered”’. Total concludes by referencing the slogan of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party, ‘“Credere, Obbedire, Combattere”’ (‘Believe, Obey, Fight’); Total’s allusion to Fascism expresses the extent to which uncritical regurgitation of well-known phrases (such as ‘Property is sacred’) enacts a fascistic form of social control founded on the internalisation of discourse. Total’s father responds with another example of sententia: ‘“Stealing is more than a crime; it’s a mistake”- Talleyrand’. ‘Why?’, asks Total. ‘Because everything that distinguishes one thing from another is property’, his father says, ‘So if you steal, you are confusing things and confusing their owners, of course. A property owner must not be confused with a non-property owner’. Total asks how much they have in the bank. ‘As much as we deserve’, his father says. Total asks if money is ‘a prize [….] A prize for what, goddamnit? For honesty?’ ‘Perhaps’, his father says. ‘So in your opinion we’re dishonest?’, Total asks, ‘No better than thieves?’  The next day, Total approaches the manager of the bank and asks for a loan. Total is offered 350,000 lire, but he protests that this isn’t enough: he wants ten million lire. ‘What for?’, the manager asks incredulously. ‘To live. To live better’, Total says, reminding the bank manager that in his career at the bank he has touched over twenty-one billion lire, ‘Not to mention all the money my father counted as an employee of this bank. We’ve never stolen anything, so you can vouch for my honesty’. Total concludes his plea by asserting, ‘Loans should be granted to people who have nothing’ – not to those who are already wealthy, like the butcher. ‘Charitable loans are good enough for them’, the bank manager says, ‘Banks are for those who have money’. In response to this, Total takes out a bank note and sets fire to it, the note slowly burning as he retreats out of the bank as if he were holding a hostage or human shield. ‘That’s sacrilege’, cries the manager. The next day, Total approaches the manager of the bank and asks for a loan. Total is offered 350,000 lire, but he protests that this isn’t enough: he wants ten million lire. ‘What for?’, the manager asks incredulously. ‘To live. To live better’, Total says, reminding the bank manager that in his career at the bank he has touched over twenty-one billion lire, ‘Not to mention all the money my father counted as an employee of this bank. We’ve never stolen anything, so you can vouch for my honesty’. Total concludes his plea by asserting, ‘Loans should be granted to people who have nothing’ – not to those who are already wealthy, like the butcher. ‘Charitable loans are good enough for them’, the bank manager says, ‘Banks are for those who have money’. In response to this, Total takes out a bank note and sets fire to it, the note slowly burning as he retreats out of the bank as if he were holding a hostage or human shield. ‘That’s sacrilege’, cries the manager.

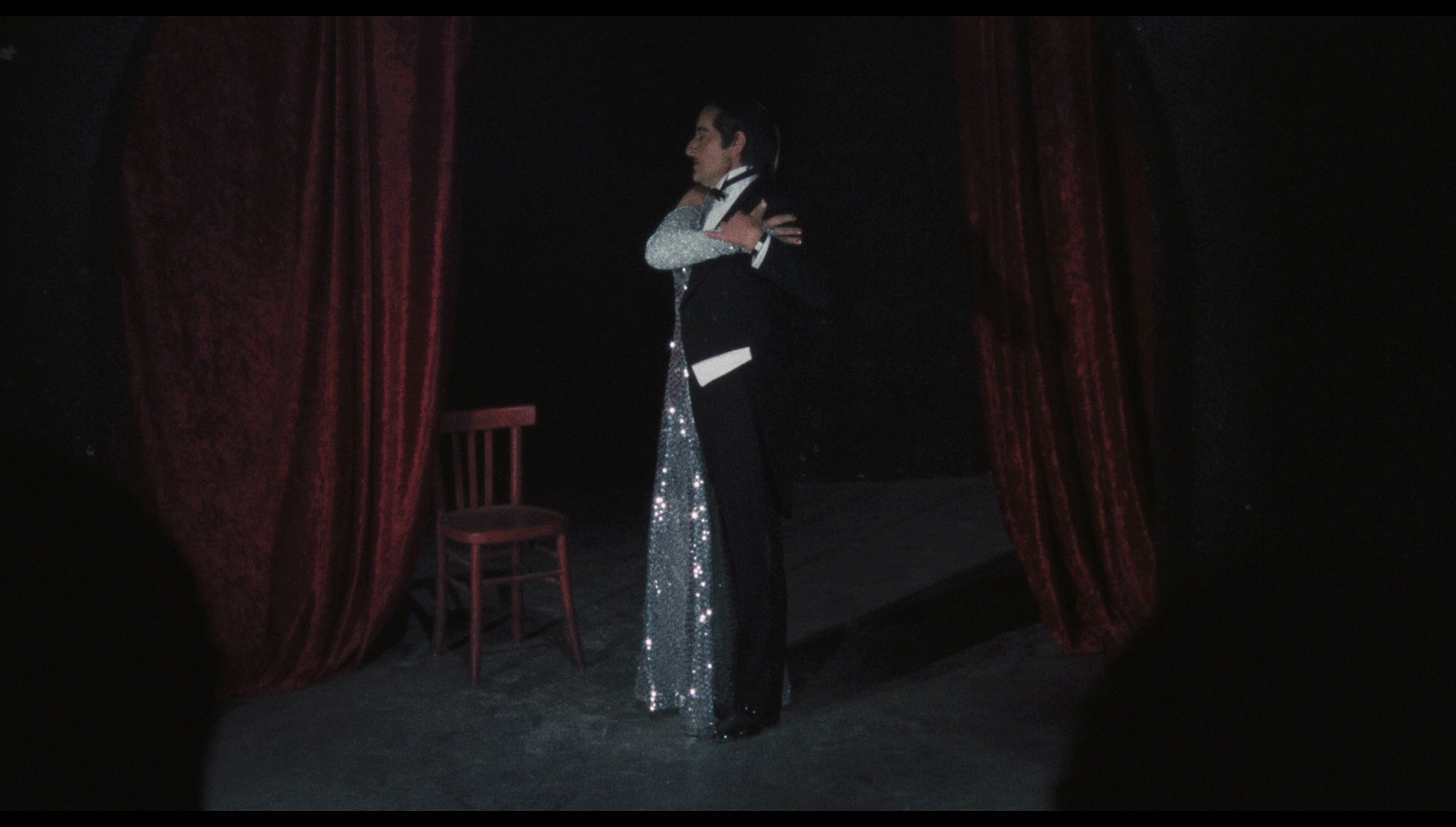

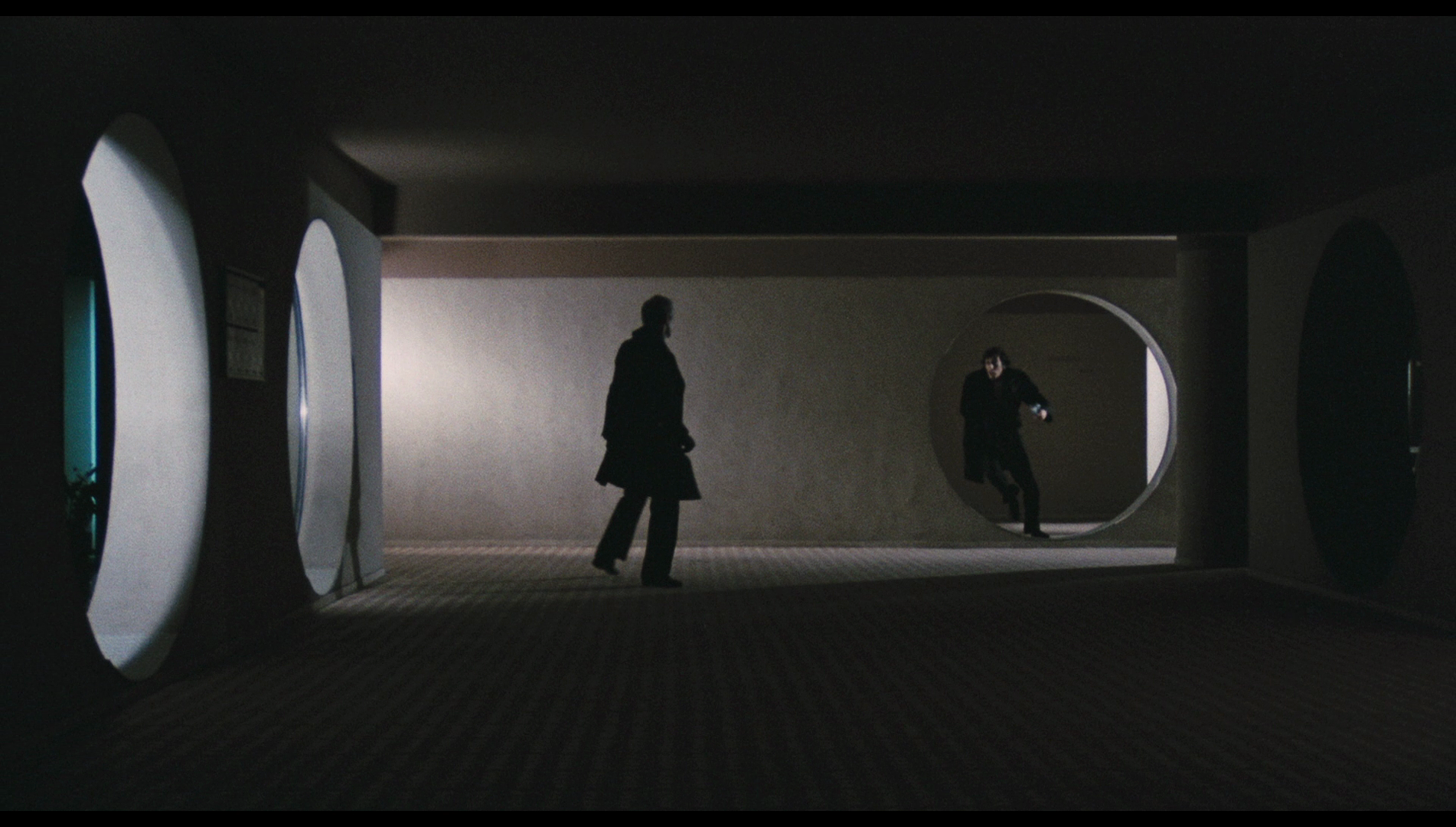

When Total begins to steal from the butcher, given his allergic response to banknotes and coins he refuses to take money, instead stealing furs, jewellery and other items. A number of times in the film, Total identifies himself as a practitioner of ‘Mandrake Marxism’, stealing only that which he needs. (Interestingly, in 2016 the Italian court of appeals suggested that it is permissible for a starving person to steal food in order to survive, and that survival is more important than concepts of ownership or property.) Total takes fine food and shares it with his father; Total’s father tucks into a tin of caviar, refusing to believe Total has stolen it. ‘Rule number one’, Total says, ‘Stolen food tastes the same as bought food’. Nevertheless, after Total has teamed up with Albertone to rob the butcher’s home of furs and jewellery, and Albertone takes Total to his ‘fence’, Total is dismayed to learn that stolen items are worth less than their market value. In response to this, Total steals the money belt from Albertone’s ‘fence’, returning with this to the home he shares with his father. The presence of the money causes Total to scratch himself. ‘I gave in’, he says, ‘I stole money for the first time [….] Stolen money is the same as money you earn by the sweat of your brow [….] Property isn’t just theft; it’s a disease’, he adds, offering an ironic spin on his father’s quoting of Talleyrand earlier in the picture. ‘To be or to have?’, Total reasons, his choice alluding to Hamlet’s famous soliloquy at the start of the ‘nunnery scene’ in Shakespeare’s play, ‘I’d like to be and to have, but I know that’s impossible. That’s the disease’. When Total threatens to burn the money, his father abandons his previous antipathy towards theft, telling Total that ‘We might as well spend it [the money]’. ‘Doesn’t it disgust you?’, Total asks, ‘I stole it!’  Elsewhere in the film, Total explains his motivations for targeting the butcher to Albertone: Total says, 'I counted his [the butcher's] money at the back. It was dirty and smelly, and it made me feel sick. I need to reduce him to poverty'. In response, Albertone tells Total that 'Nobody ever ended up in poverty because of theft, you idiot [….] If you want to steal, do it to get rich like everyone else’. However, shortly afterwards Albertone confesses to Total that ‘Poverty’s all you can earn as a thief’. Total, the 'Mandrakian Marxist', is contrasted with the professional thief Albertone and his gang. A Fagin-esque character, Albertone is introduced in a nightclub cabaret performance in which he performs a decadent 'half and half' act, one half of his body dressed as a man and the other half dressed and made up as a woman. Albertone's decadence is also signalled backstage, when he grabs and fondles the groin of one of his young male accomplices. When Total and Albertone meet by accident, whilst both of them are robbing the same house, Total offers Albertone help in escaping; Albertone reminds Total that 'We [professional thieves] are like wolves. We'll bite it [the hand offered to help them] off'. Elsewhere in the film, Total explains his motivations for targeting the butcher to Albertone: Total says, 'I counted his [the butcher's] money at the back. It was dirty and smelly, and it made me feel sick. I need to reduce him to poverty'. In response, Albertone tells Total that 'Nobody ever ended up in poverty because of theft, you idiot [….] If you want to steal, do it to get rich like everyone else’. However, shortly afterwards Albertone confesses to Total that ‘Poverty’s all you can earn as a thief’. Total, the 'Mandrakian Marxist', is contrasted with the professional thief Albertone and his gang. A Fagin-esque character, Albertone is introduced in a nightclub cabaret performance in which he performs a decadent 'half and half' act, one half of his body dressed as a man and the other half dressed and made up as a woman. Albertone's decadence is also signalled backstage, when he grabs and fondles the groin of one of his young male accomplices. When Total and Albertone meet by accident, whilst both of them are robbing the same house, Total offers Albertone help in escaping; Albertone reminds Total that 'We [professional thieves] are like wolves. We'll bite it [the hand offered to help them] off'.

Reflecting on the difference between the 'haves' and 'have nots', Albertone tells Total – when both of them are almost caught by the butcher - 'We may be afraid now, but they [the wealthy] live their lives in fear' - the fear that their property will be taken from them, either by criminals or by the state. Albertone dies whilst under interrogation from the brigadier; in post-Giuseppe Pinelli Italy, the brigadier surprisingly breaks down and panics, fearing the consequences of Albertone's death in the interrogation room. ‘Who’s going to protect me from the newspapers?’, the brigadier questions desperately, ‘No-one trusts us anymore. We don’t even trust each other’. With this moment, the film comes back round to the incident that seemed to spur Petri on to create his most best and most lasting films, the death of Pinelli and the impact this event had upon the relationships between society and its figures of authority. At Albertone’s funeral, a fellow thief, Paco (Luigi Proietti), delivers a bold, impassioned speech listened to by an audience of thieves: ‘What would the world be without us?’, Paco asks his listeners, ‘Think about it. How many of these bastards who call themselves honest men would be in the gutter? […] What would locksmiths do without thieves? And lock factories? […] And all the bank workers, the night watchmen, the police? […] Society owes its established order and social equilibrium to us, because we […] cover up the thieves who operate with legality’.

Video

This new presentation is based on a digital restoration by the Museo Nazionale del Cinema and the Cineteca di Bologna. The 2k digital restoration uses as its source a 4k scan of the film’s original negative. This new presentation is based on a digital restoration by the Museo Nazionale del Cinema and the Cineteca di Bologna. The 2k digital restoration uses as its source a 4k scan of the film’s original negative.

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1; the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 27Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The film is uncut and runs for 126:13. An extremely rich level of detail is present throughout the picture, fine detail becoming particularly evident in the film’s close-ups. There is no print damage to speak of, and contrast levels are superb. The blacks are deep and rich, the highights balanced and the midtones are defined strongly. Colour reproduction is very good too, with the film being dominated by earthy tones that fit the subject matter perfectly. There is no evidence of harmful digital tinkering. Finally, an excellent encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is clean and clear throughout, Morricone’s rasping score being communicated very well. Optional English subtitles are provided, and these are easy to read and offer an accurate translation of the Italian dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘My Name is Total’ (19:46). This new interview with actor Flavio Bucci begins with some general reflections on Petri’s work and his reputation. Bucci talks about his work in theatre and the relationships between Italian theatre and the cinema of the 1970s. Bucci argues that ‘new problems [and] new issues’ required ‘new ways of telling a story’. He describes Petri as ‘my teacher’ and says Petri was the person he learnt the most from. ‘He treated me like the son he never had’, Bucci asserts. Bucci reflects on The Working Class Goes to Heaven, his first collaboration with Petri, and talks about working with Gian Maria Volonte on that film. From here, Bucci comments on Property is No Longer Theft, situating the picture within Petri’s body of work and discussion Petri’s approach to storytelling and his focus on ‘engaged cinema’. The interview is in Italian with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Middle-Class Communist’ (23:33). The film’s producer Claudio Mancini talks about meeting Petri through Giuliano Montaldo. Mancini says that ‘I got along great with Petri’, although Petri had a tendency to look at Mancini and say things like ‘“You represent the power” and all that nonsense’. ‘He was too much a lefty’, Mancini says. Mancini suggests Property Is No Longer a Theft was only a success because ‘deep down, Italians are dirty’ and they revelled in scenes such as the one in which Anita fucks the butcher whilst wearing the stocking over her head: ‘For the first time, there was a woman on top of a man’, Mancini says, ‘They banned it, then allowed it. And it spread all over Italy’. Petri ‘may have been a fervent Communist but […] he kept on buying houses’, Mancini comments. Mancini recollects the shooting of The Working Class Goes to Heaven, during which production was interrupted by ‘about ten Maoists’; Mancini claims he wanted to settle this dispute quietly but Volonte assaulted the Maoists verbally and ‘attempted to throw a punch but fell’. Petri became involved and ‘a fight broke out’. This interview is also in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘The Best Man’ (23:04). A new interview with make-up artist Pierantonio Mecacci focuses on Mecacci’s working relationship with Petri. Mecacci reflects with particular fondness his work with Petri, Volonte and Bucci on The Working Class Goes to Heaven. Again, this interview is in Italian with optional English subtitles. Retail versions of the disc include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet containing a new article about the film by Camilla Zamboni.

Overall

Though deeply rooted in the anni di piombo and the fallout from the death of Pinelli, Property is No Longer Theft is as incendiary today as it was in the mid-1970s: the issues addressed within the film are as prevalent to the 21st Century as they were forty years ago, and arguably more so. It’s a powerful film, the Brechtian techniques employed by Petri still standing in stark contrast to the dominant paradigms of narrative cinema. In interviews, the documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles used to remind audiences of the two meanings of the word ‘entertainment’: ‘diversion’ and ‘engagement’ (see Maysles, quoted in Cole, 2006: np). Petri’s cinema foregrounds the latter, angrily countering the idea that cinema should be a form of ‘diversion’ and pushing the audience towards a sense of engagement with society and the deep rifts that exist within it. Whilst much more driven by caricature and grotesquerie, and therefore filled with more (black) comedy than ‘Three Hypotheses in the Death of Giuseppe Pinelli’, Property is No Longer Theft shares a similar context and very similar ideas – the cultural shift that took place after Pinelli’s death being highlighted within the sequence in which Albertone dies whilst in police custody. Though deeply rooted in the anni di piombo and the fallout from the death of Pinelli, Property is No Longer Theft is as incendiary today as it was in the mid-1970s: the issues addressed within the film are as prevalent to the 21st Century as they were forty years ago, and arguably more so. It’s a powerful film, the Brechtian techniques employed by Petri still standing in stark contrast to the dominant paradigms of narrative cinema. In interviews, the documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles used to remind audiences of the two meanings of the word ‘entertainment’: ‘diversion’ and ‘engagement’ (see Maysles, quoted in Cole, 2006: np). Petri’s cinema foregrounds the latter, angrily countering the idea that cinema should be a form of ‘diversion’ and pushing the audience towards a sense of engagement with society and the deep rifts that exist within it. Whilst much more driven by caricature and grotesquerie, and therefore filled with more (black) comedy than ‘Three Hypotheses in the Death of Giuseppe Pinelli’, Property is No Longer Theft shares a similar context and very similar ideas – the cultural shift that took place after Pinelli’s death being highlighted within the sequence in which Albertone dies whilst in police custody.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release is phenomenal; the film has long been unavailable on home video, at least outside Italy. Arrow’s Blu-ray release of this film is therefore incredibly welcome. The presentation of the main feature is excellent, and the film is also accompanied by some good contextual material. Speaking personally, this is a strong contender for one of the most significant home video releases of the year. References: Curti, Roberto, 2013: Italian Crime Filmography: 1968-1980. London: McFarland Foot, John, 2007: ‘The Death of Giuseppe Pinelli: Truth, Representation, Memory’. In: Gundle, Stephen & Rinaldi, Lucia (eds), 2007: Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy: Transformations in Society and Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan: 59-72 Cole, Williams, 2006: ‘Uncontrolled Cinema: Albert Maysles’. In: The Brooklyn Rail (10 July, 2006) [Available online at: http://brooklynrail.org/2006/07/film/uncontrolled-cinema]

|

|||||

|