|

The Film

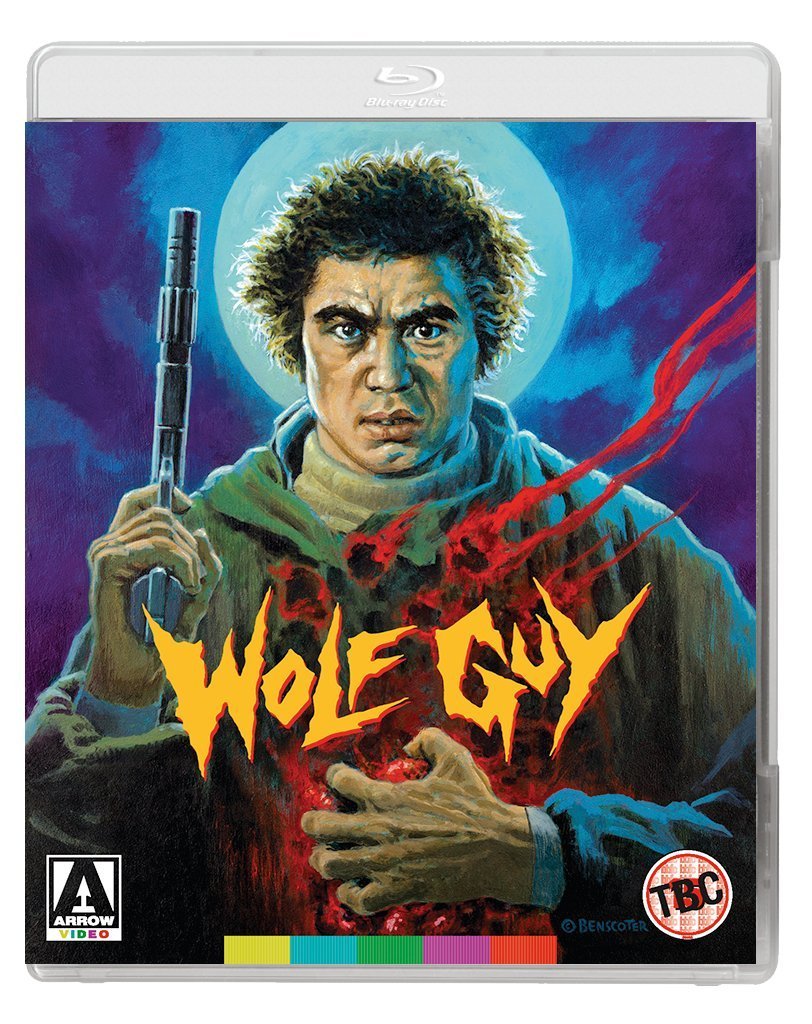

Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope (Yamaguchi Kazuhiko, 1975) Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope (Yamaguchi Kazuhiko, 1975)

Also known as Wolfman Vs The Supernatural and Wolfguy – The Burning Lycanthrope, Yamaguchi Kazuhiko’s Wolf Guy: Enraged Lycanthrope (1975) is one of the more bizarre, and previously quite difficult to see, Sonny Chiba-starring pictures of the 1970s. Based on a manga by Kazumasa Hirai and made roughly contemporaneously with the Waldemar Daninsky werewolf pictures that starred Paul Naschy (the Anglicised screen name of Jacinto Molina) and which began with Enrique L Eguiluz’ Le marca del Hombre Lobo (Mark of the Wolfman/Frankenstein’s Bloody Terror) in 1968, Wolf Guy has some similarities with those films in terms of its marriage of the mythology of the werewolf, often seen as ‘quaint’ by modern viewers, on to a story containing the explicit sex and violence that became prevalent on the screen following the relaxation of attitudes towards film censorship in various countries during the late 1960s.

In the same year as the release of Wolf Guy, Paul Naschy starred in Miguel Iglesias’ La maldición de la bestia (Night of the Howling Beast/The Werewolf and the Yeti). Iglesisas’ film is a strange hodgepodge of the paradigms of different subgenres, featuring a plot in which the lycanthrope Count Waldemar Daninsky journeys to Tibet and encounters a yeti(!) Almost like a ‘call and response’ to the Naschy picture, Wolf Guy features a similar fusion of elements from specific (sub)genres that will likely make a first time viewer’s jaw hit the floor. The film incorporates elements of the moody jitsuroku (‘reality’) yakuza films of the 1970s, which began with Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity in 1973 and featured many similarities with the semidocumentary films noir that included gritty documentary-style photography and a focus on alienation within an urban milieu, alongside a David Cronenberg-style plot that involves a mysterious government agency (the JCIA) which is tasked with exploring the potential to weaponise psychic or other supernatural powers – rather like the CIA’s ‘Stargate’ programme that concentrated on ‘remote viewing’ as a potential method of gathering intelligence.

The film begins on the city streets, with a man fleeing through a crowd, declaring loudly that ‘The Tiger is coming! [….] I’ll get killed [….] Miki has cursed us’. The man runs into journalist ‘Wolf’ Inugami (Sonny Chiba), who witnesses the fleeing man being torn to pieces by invisible claws. Inugami has a fleeting vision of a tiger in the city. He is interviewed by the police, who accuse Inugami of having some input into the man’s death. However, Inugami is released when the police get the results of the autopsy – which reveals to them that no human could have caused the injuries that killed the victim. The film begins on the city streets, with a man fleeing through a crowd, declaring loudly that ‘The Tiger is coming! [….] I’ll get killed [….] Miki has cursed us’. The man runs into journalist ‘Wolf’ Inugami (Sonny Chiba), who witnesses the fleeing man being torn to pieces by invisible claws. Inugami has a fleeting vision of a tiger in the city. He is interviewed by the police, who accuse Inugami of having some input into the man’s death. However, Inugami is released when the police get the results of the autopsy – which reveals to them that no human could have caused the injuries that killed the victim.

Inugami is met by his friend Arai, who tells Inugami that the dead man was a former musician named Hanamura. Three of the members of Hanamura’s band were killed in a similar way; only one member of the band survives, a man named Hiruma. Armed with this information, Inugami tracks down Hiruma and interviews him. Now a drunk, Hiruma reveals that Miki was a singer: ‘We just took turns fucking her, that’s all’, Hiruma says. One of the men in the group transmitted syphilis to Miki, leading to Miki becoming ‘hooked on smack’.

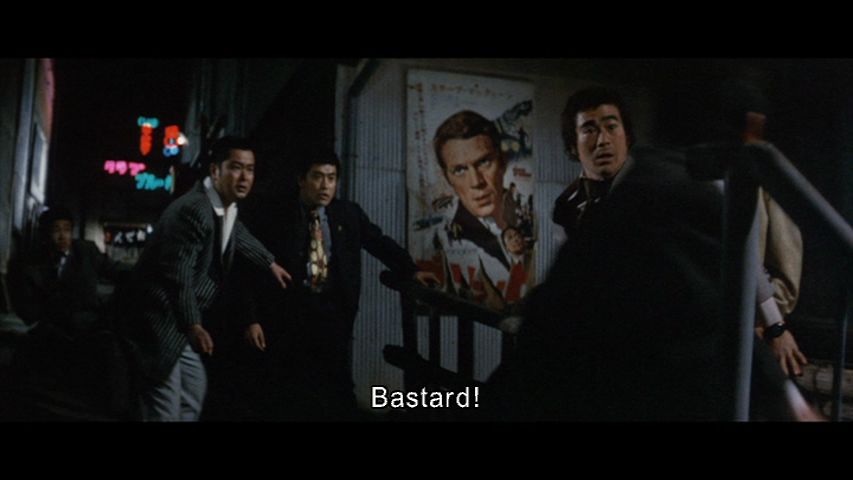

Inugami’s interview with Hiruma is interrupted by a group of street thugs allied with the Yakuda family, who demand that Inugami hand Hiruma over to them. A fight ensues; Inugami is wounded in the shoulder. He flees and is picked up by a girl on a motorbike, who returns with Inugami to her home before seducing the reporter.

Later, Arai brings to Inugami the resumé of Miki. Miki was contracted to Manabe Pro, the same agency that managed Hanamura’s band. The owner of Manabe Pro is Keiichi Manabe, and Arai tells Inugami that Manabe ordered Hanamura’s band to rape Miki; this treatment was apparently owing to Miki’s ‘attitude problem’.

Inugami tracks down Miki, who is working as a singer in a seedy strip club. Backstage, Inugami makes an attempt to talk to Miki; she’s a shivering, desperate wreck who is in need of her ‘fix’. Wandering the streets in search of a ‘hit’, Miki is accosted by the Yakuda gang, but she is saved by Inugami who displays superhuman strength and agility in dispatching the street thugs. However, Inugami discovers Arai has been mortally wounded by the same gang of hoodlums. Before he dies, Arai tells Inugami the full story of Miki: she was a promising singer who fell in love with the son of a conservative politician, Fukunuka. Fukunuka disapproved of his son’s relationship with Miki, fearing it would impact on his political ambitions, and ordered Manabe to have Miki gang-raped by Hanamura’s band. Photographs of the act were passed on to Miki’s lover, leading Miki into a spiral of self-destructive behaviour. Inugami tracks down Miki, who is working as a singer in a seedy strip club. Backstage, Inugami makes an attempt to talk to Miki; she’s a shivering, desperate wreck who is in need of her ‘fix’. Wandering the streets in search of a ‘hit’, Miki is accosted by the Yakuda gang, but she is saved by Inugami who displays superhuman strength and agility in dispatching the street thugs. However, Inugami discovers Arai has been mortally wounded by the same gang of hoodlums. Before he dies, Arai tells Inugami the full story of Miki: she was a promising singer who fell in love with the son of a conservative politician, Fukunuka. Fukunuka disapproved of his son’s relationship with Miki, fearing it would impact on his political ambitions, and ordered Manabe to have Miki gang-raped by Hanamura’s band. Photographs of the act were passed on to Miki’s lover, leading Miki into a spiral of self-destructive behaviour.

Inugami forms an alliance with Miki, vowing to help her overcome her addiction and find treatment for her syphilis. Inugami’s encounter with Miki encourages him to reflect on his childhood: Inugami is the only surviving member of his clan, a group of werewolves who, when Inugami was a small child, were massacred by gun-wielding locals.

Inugami confronts Manabe, warning him that Miki has the inexplicable power to give her hatred and anger a physical manifestation in the form of a tiger; and Miki hates Manabe most of all. Shortly afterwards, an attempt is made on Miki’s life. Inugami saves Miki, but both of them are captured by a mysterious group of people who work for the JCIA (Japan Cabinet Intelligence Agency). The JCIA experiment with both Miki and Inugami’s powers. However, Inugami manages to escape, fleeing to the place where he was raised and where his clan was massacred. Inugami comes under fire from the descendants of those who massacred his clan; he meets and is aided by a young woman named Taka, the daughter of a friend of Inugami’s mother. The stage is set for a confrontation between Inugami, those who massacred his clan, and the JCIA.

Like the protagonist of any number of films noir, Inugami is a journalist. He begins the story with a typically hardboiled example of voiceover narration: ‘Tonight smells like another bloody incident perpetrated by humanity’, he asserts cynically. The hardboiled dialogue continues throughout the film. Later in the story, after speaking with Miki, Inugami narrates: ‘There is a nastier pathogen than syphilis. It’s the one they call hatred of humans’. Though Inugami is not a criminal, the police treat him as a nuisance (‘Wherever you go, there’s always some incident’, he is told whilst the police interview him about the death of Hanamura). Met by Arai outside the police station, Inugami is told ‘You always get involved in some kind of trouble?’ ‘Are you another hyena looking for scraps?’, Inugami asks coldly. Like the protagonist of any number of films noir, Inugami is a journalist. He begins the story with a typically hardboiled example of voiceover narration: ‘Tonight smells like another bloody incident perpetrated by humanity’, he asserts cynically. The hardboiled dialogue continues throughout the film. Later in the story, after speaking with Miki, Inugami narrates: ‘There is a nastier pathogen than syphilis. It’s the one they call hatred of humans’. Though Inugami is not a criminal, the police treat him as a nuisance (‘Wherever you go, there’s always some incident’, he is told whilst the police interview him about the death of Hanamura). Met by Arai outside the police station, Inugami is told ‘You always get involved in some kind of trouble?’ ‘Are you another hyena looking for scraps?’, Inugami asks coldly.

The film foregrounds patriarchal violence via the plot’s emphasis on the cruel treatment of Miki, a singer, at the behest of big-shot music mogul Keiichi Manabe and politician Fukunuka, who was angered at Miki’s affair with his son. The real villains of the piece are these two wealthy, powerful patriarchs; the music ‘industry’ is depicted as being run by such men, their connections with corrupt politicians marking them as distrustful. ‘He was your typical showbiz scumbag’ who preyed on girls and ran drugs, Arai tells Inugami by way of eulogy for Hanamura.

About two thirds of the way into the narrative, Wolf Guy shifts its focus on to the JCIA and their activities. The name obviously intended to echo the CIA, the JCIA seem to specialise in examining the potential to weaponise various supernatural abilities, including Wolf’s lycanthropy, which gives him the power to repair damage caused to his body, and Miki’s ability to use her anger to kill. ‘The tiger is an incarnation of Miki’s hatred’, Inugami tells Manabe, ‘You could call it Miki’s evil spirit’. Later, a senior figure within the JCIA queries, ‘Can a grudge actually kill people?’ With its emphasis on the shadowy netherworld in which this government agency operates, Wolf Guy anticipates the paranoid examination of government programmes to weaponise psychic powers in films such as David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981) and, also, The X-Files (Fox, 1993-2001).

The JCIA experiment with both Inugami and Miki. Within the JCIA’s headquarters, Miki is presented with Manabe; the intention is to test her powers by provoking her anger. Manabe is, of course, torn to shreds by the tiger that Miki channels. ‘Miki Ogata has become the perfect robot’, the head of the JCIA observes afterwards. Inugami, however, is tested via a surgical operation which seems designed to prove his immortality and healing powers, similar to those of Wolverine in the X-Men comics. In a surgery, Inugami is disembowelled whilst conscious. What seems to be real footage of a surgical operation, partially concealed by the negativising of the image, is presented to the audience, to show the members of the JCIA cutting in to Inugami’s body. The use of such footage links the film to other 1970s productions that incorporate similarly gruesome material – including Rene Cardona’s La horripilante bestia humana (Night of the Bloody Apes, 1969), which famously incorporates real footage of open heart surgery, and Manuel Cano’s El pantano de los cuervos (The Swamp of the Ravens, 1974), which briefly features footage of an autopsy. When Inugami manages to escape from the JCIA, he battles through wave upon wave of ninja-suited guards before coming face-to-face with a man who claims to have ‘received a transfusion of your blood and became a wolf man too’. After a protracted fight, Inugami emerges as the victor, reflecting in his narration that ‘Mixing wolf blood with his human blood had given him blood poisoning. Is this proof that werewolves and humans can never mix?’ The JCIA experiment with both Inugami and Miki. Within the JCIA’s headquarters, Miki is presented with Manabe; the intention is to test her powers by provoking her anger. Manabe is, of course, torn to shreds by the tiger that Miki channels. ‘Miki Ogata has become the perfect robot’, the head of the JCIA observes afterwards. Inugami, however, is tested via a surgical operation which seems designed to prove his immortality and healing powers, similar to those of Wolverine in the X-Men comics. In a surgery, Inugami is disembowelled whilst conscious. What seems to be real footage of a surgical operation, partially concealed by the negativising of the image, is presented to the audience, to show the members of the JCIA cutting in to Inugami’s body. The use of such footage links the film to other 1970s productions that incorporate similarly gruesome material – including Rene Cardona’s La horripilante bestia humana (Night of the Bloody Apes, 1969), which famously incorporates real footage of open heart surgery, and Manuel Cano’s El pantano de los cuervos (The Swamp of the Ravens, 1974), which briefly features footage of an autopsy. When Inugami manages to escape from the JCIA, he battles through wave upon wave of ninja-suited guards before coming face-to-face with a man who claims to have ‘received a transfusion of your blood and became a wolf man too’. After a protracted fight, Inugami emerges as the victor, reflecting in his narration that ‘Mixing wolf blood with his human blood had given him blood poisoning. Is this proof that werewolves and humans can never mix?’

As if in answer to Inugami’s question, throughout the film women throw themselves at Chiba: a good deal of the plot revolves around how irresistible his character is to women. After his confrontation with the street thugs who threaten Hiruma, Inugami is picked up by a woman on a motorbike who takes him back to her apartment. She unzips her leather catsuit to reveal that underneath it, she is naked; she then licks Inugami’s bloody hand, telling him, ‘Give it to me. You’re not human [….] Right now, I’m just a woman who wants an animal’. When Inugami meets Miki, he sees in her another outsider with a paranormal talent and becomes committed to helping her; Miki cannot understand why he would wish to do this. ‘Why’d you want to help a stinking corpse?’, she asks him. ‘Your illness can be treated, as can your addiction’, Inugami tells her. He suggests they get the money for her treatment from Manabe, but Miki scoffs at this idea. She is filled with self-pity, asking Inugami, ‘Can you fuck me knowing I have syphilis and a drug habit? Of course not. Then why can you help me?’ Determined to prove himself to Miki, Inugami seduces her, but she protests that she is ‘contagious’, telling him ‘There’s no point anyway: I won’t feel anything’. ‘Will you love me and make me feel I am still alive?’, Miki asks Inugami. Towards the end of the film, Inugami meets Taka and becomes involved with her. Taka reveals herself to be the daughter of a friend of Inugami’s mother who was named after Inugami’s mother. She offers herself to Inugami, telling him ‘Let my body give you some relief, if only for a while’. Inugami embraces her, kissing her breasts and remembers suckling at his mother’s nipple. ‘How strange’, Inugami observes, ‘It’s like being reborn [….] You are my mother. And also my wife’. At the climax of the film, the JCIA arrive and attempt to have Miki destroy Inugami by revealing to her Inugami’s relationship with Taka; Miki becomes angered at Inugami’s perceived betrayal of her, and the final conflict within the film is not between Inugami and the JCIA but between Miki and Taka.

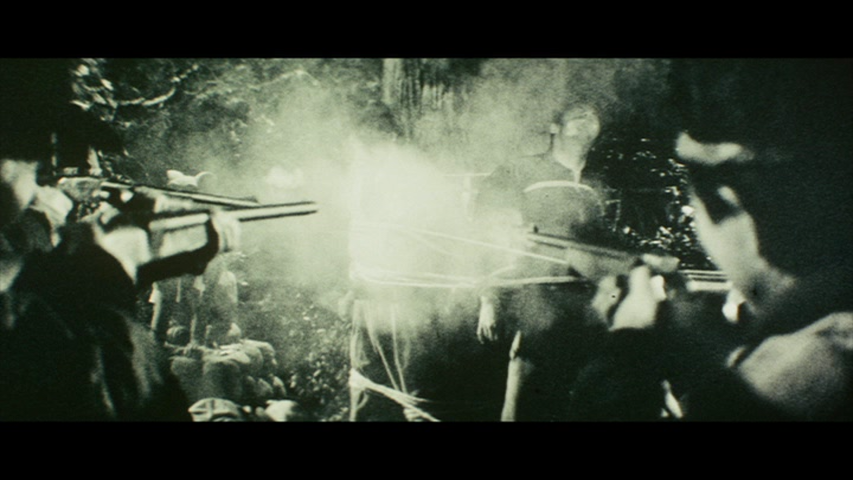

Wolf’s memories of the massacre of his clan are depicted by flashbacks, shot on monochrome stock with severe grain and looking for all intents and purposes like a photograph in the are, bure, bokeh (‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’) style popularised by the likes of Daido Moriyama, Yutaka Takanashi and Takuma Nakahira in the pages of the experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70). The massacre itself is framed almost like a wartime atrocity, with the attackers rounding up innocent civilians and killing men, women and children – leaving only the young Wolf as the sole survivor – much like the images from the massacres at My Lai or perhaps even Nanking. Wolf is left nursing his dying mother, who tells him that ‘You’re the last […] wolf. The humans have wiped us out. The responsibility to avenge the entire wolf tribe lies with you now; and you will be invincible’. Wolf’s memories of the massacre of his clan are depicted by flashbacks, shot on monochrome stock with severe grain and looking for all intents and purposes like a photograph in the are, bure, bokeh (‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’) style popularised by the likes of Daido Moriyama, Yutaka Takanashi and Takuma Nakahira in the pages of the experimental Japanese photography magazine Purovōku: shisō no tame no chōhatsuteki shiryō/Provoke: Provocative Documents for the Sake of Social Thought (1968-70). The massacre itself is framed almost like a wartime atrocity, with the attackers rounding up innocent civilians and killing men, women and children – leaving only the young Wolf as the sole survivor – much like the images from the massacres at My Lai or perhaps even Nanking. Wolf is left nursing his dying mother, who tells him that ‘You’re the last […] wolf. The humans have wiped us out. The responsibility to avenge the entire wolf tribe lies with you now; and you will be invincible’.

With this, Inugami’s position as the last of his kind is sealed; the film itself is also one of a kind, a bizarre mish-mash of elements from yakuza pictures with David Cronenberg-style SF/horror. It’s a delirious, comic book-like film whose cardinal sin, perhaps, is trying to cram too much plot into a ninety minute running time.

Video

For the purposes of this review, we were presented only with a check disc of the DVD included in retail copies of the release, and not the Blu-ray disc. For the purposes of this review, we were presented only with a check disc of the DVD included in retail copies of the release, and not the Blu-ray disc.

On the DVD provided for review, Wolf Guy has a running time of 85:57 mins (NTSC). The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD. As with many Japanese films shot anamorphically during this period, the lenses used in the making of the picture don’t seem to have been the greatest: the image is often sharp in the centre, trailing off into soft haziness at the periphery of the frame. The film also makes some interesting use of split dioptre lenses. The presentation itself contains a good level of detail, and has some pleasing contrast levels. The 35mm colour photography is rendered well. Midtones have a strong sense of definition to them, although blacks often seem ‘crushed’; whether this is also true for the HD presentation on the Blu-ray disc, we are unable to say at this juncture. Nevertheless, the DVD contains a satisfying presentation of the film.

Audio

Audio, on the DVD provided for review, is via a Dolby Digital 1.0 mono track with optional English subtitles. The track is audible throughout, the funky score featuring a rounded representation. The subtitles are free from distracting errors and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Kazuhiko Yamaguchi: Movies with Guts’ (10:31). This new interview with Yamaguchi sees the director reflecting on his career at Toei. He discusses his career to the point of directing Wolf Guy and admits that prior to making the film, he hadn’t read the manga on which it was based and, when he did, he wondered if the film was a ‘worthy’ project. He talks about the difficulties in managing the effects required for the film, and reflects on Sonny Chiba’s approach to acting. The interview is in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Toru Yoshida: B-Movie Monster’ (17:31). Interviewed for this release, producer Yoshida reflects on his work at Toei as a production assistant and, later, a producer. Yoshida too reveals that he had not read the manga prior to being given control of the Wolf Guy project, even though they were extraordinarily popular at the time. He suggests that the film was ‘made in no time’ and the director ‘didn’t take it too seriously either’. He reflects that ‘if I’d done it properly, then it would have been a hit’. This interview is also in Japanese, with optional English subtitles.

- ‘Sonny Chiba: A Life in Action, Vol 1’ (14:31). Sonny Chiba discusses his career in a new interview shot for Arrow. He discusses being typecast as an action star and reflects on his approach to shoting action.

- Trailer (2:56).

Overall

As oddball a werewolf film as Rino Di Silvestro’s La lupa manera (Werewolf Woman), released the following year, Wolf Guy’s roots in a manga are writ large throughout the picture. It’s a deliriously entertaining film, though the narrative shoots off in all sorts of directions and the picture struggles to contain all of the ideas contained within it. The result is an unfocused film with enough story for two or three pictures crammed into a ninety minute running time. Nevertheless, there’s much to enjoy in this mish-mash of yakuza pictures and elements from SF/horror cinema. As oddball a werewolf film as Rino Di Silvestro’s La lupa manera (Werewolf Woman), released the following year, Wolf Guy’s roots in a manga are writ large throughout the picture. It’s a deliriously entertaining film, though the narrative shoots off in all sorts of directions and the picture struggles to contain all of the ideas contained within it. The result is an unfocused film with enough story for two or three pictures crammed into a ninety minute running time. Nevertheless, there’s much to enjoy in this mish-mash of yakuza pictures and elements from SF/horror cinema.

Arrow’s presentation of this previously hard-to-see film is pretty pleasing, at least on the DVD we were given for review. The film itself is supported with some good contextual material in the form of interviews with Chiba, director Yamaguchi and producer Yoshida. Fans of outrageous Japanese 1970s action cinema will find plenty to enjoy in this release.

|