|

|

Panic in the Streets (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th August 2017). |

|

The Film

Panic in the Streets (Elia Kazan, 1950) Panic in the Streets (Elia Kazan, 1950)

During a card game, ailing Armenian immigrant Kochak (Lewis Charles), who has arrived in New Orleans after stowing away on the commercial ship Nile Queen, provokes the ire of hoodlum Blackie (Jack Palance, in his first feature film role). Aided by his hangers-on Fitch (Zero Mostel) and Poldi (Tommy Cook), Blackie pursues Kochak through the maze of warehouses near the port, finally cornering the Armenian and killing him. Kochak’s body is discovered the next day and taken to the morgue, where it is discovered that Kochak was infected with pneumonic plague, the pulmonary variant of bubonic plague. Dr Clinton Reed (Richard Widmark), an employee of US Public Health Service, is called away from his family – wife Nancy (Barbara Bel Geddes) and young son Tommy (Tommy Rettig) – to investigate the case. Reed persuades the mayor and other senior figures to keep the news of Kochak’s infection from the press, for fear of panicking the city’s populace – which, Reed reasons, could lead to the plague being dispersed to other cities and states. However, Reed faces some resistance from police captain Tom Warren (Paul Douglas), who believes Reed is simply exploiting an opportunity to further his career. Reed and Warren are forced to work together, to identify the killers of Kochak and quarantine them, thereby preventing the plague from spreading further. Reed estimates that they have less than forty-eight hours to find Kochak’s murderers before the city is faced with an epidemic of the plague.  Meanwhile, Blackie becomes obsessed with a ‘hunch that he [Kochak] brung something in and they’re [the police are] looking for it’. He gradually becomes convinced that Poldi took what Kochak brought into the country – unaware that what Kochak passed to Poldi was not riches but was instead the pneumonic plague. Blackie seeks to eliminate Poldi and get his hands on the loot he believes Poldi to have in his possession. Meanwhile, Blackie becomes obsessed with a ‘hunch that he [Kochak] brung something in and they’re [the police are] looking for it’. He gradually becomes convinced that Poldi took what Kochak brought into the country – unaware that what Kochak passed to Poldi was not riches but was instead the pneumonic plague. Blackie seeks to eliminate Poldi and get his hands on the loot he believes Poldi to have in his possession.

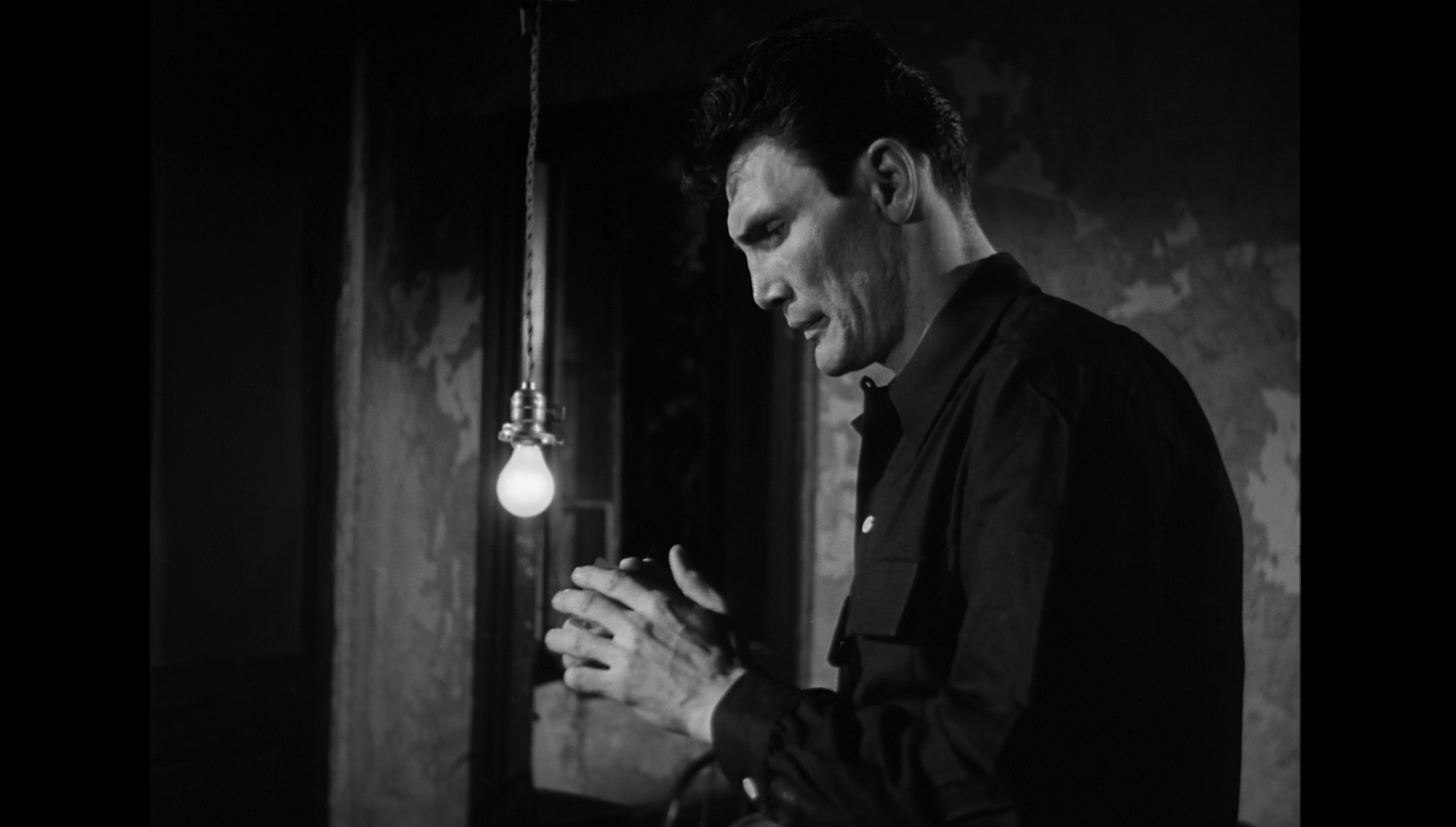

Set and filmed completely in New Orleans, Panic in the Streets was the first of a number of films that director Elia Kazan would make about the Deep South, and was followed by Baby Doll (1956), A Face in the Crowd (1957), Wild River (1960) and, of course A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). Like the same director’s earlier film noir Boomerang! (1947), Panic in the Streets fits many of the paradigms of the semidocumentary films noir; this specific subgroup of films noir is usually cited as beginning with The House on 92nd Street in 1945, in which director Henry Hathaway used some of the techniques associated with newsreels to give the film’s narrative a sense of authenticity. The storytelling methods employed within The House on 92nd Street later found their way into other films noir such as 13 Rue Madeline in 1947, Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery in 1950, and perhaps the most iconic of the semidocumentary films noir, Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948). Like the other semidocumentary films noir, Panic in the Streets emphasises the realism of its story via the heavy use of location photography (the whole picture was shot in New Orleans), the employment of non-professional actors, and an emphasis on the procedural elements of the story. However, unlike most of the semidocumentary noirs, Panic in the Streets does not feature the voice of an omniscient narrator to guide the viewer’s interpretation of the story.  The naturalism of the film can be seen from the opening sequence onwards. As the film opens, Kochak, Blackie, Fitch and Poldi are shown participating in a card game in a dive near the docks. The room they are in has a bare lightbulb; the walls are peeling. The set reeks of poverty and despair; this texture follows Blackie and his associates throughout the various spaces (tenements, warehouses, bars) through which they move in the city. Shortly afterwards, following the discussion of Kochak’s body, we see the police and morgue attendants going about their business. Rather than solemnly discussing the case at hand, the morgue attendant, Kleber (George Ehmig), speaks casually with his friend about their plans for dinner, joking about a particular restaurant and the flirtatious attentions of a specific waitress, thereby reinforcing the sense that, for these men, the investigation of a corpse is simply a part of his daily grind. (‘Don’t waste time’, Kleber tells his colleague whilst surveying Kochak’s corpse, ‘Cause I’m real hungry’.) Though this type of dialogue is probably taken for granted today, thanks to its use in naturalistic television procedurals such as NYPD Blue (Fox, 1993-2005) and Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-9), to a greater extent it originated with the semidocumentary films noir like Panic in the Streets. The naturalism of the film can be seen from the opening sequence onwards. As the film opens, Kochak, Blackie, Fitch and Poldi are shown participating in a card game in a dive near the docks. The room they are in has a bare lightbulb; the walls are peeling. The set reeks of poverty and despair; this texture follows Blackie and his associates throughout the various spaces (tenements, warehouses, bars) through which they move in the city. Shortly afterwards, following the discussion of Kochak’s body, we see the police and morgue attendants going about their business. Rather than solemnly discussing the case at hand, the morgue attendant, Kleber (George Ehmig), speaks casually with his friend about their plans for dinner, joking about a particular restaurant and the flirtatious attentions of a specific waitress, thereby reinforcing the sense that, for these men, the investigation of a corpse is simply a part of his daily grind. (‘Don’t waste time’, Kleber tells his colleague whilst surveying Kochak’s corpse, ‘Cause I’m real hungry’.) Though this type of dialogue is probably taken for granted today, thanks to its use in naturalistic television procedurals such as NYPD Blue (Fox, 1993-2005) and Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-9), to a greater extent it originated with the semidocumentary films noir like Panic in the Streets.

Steve Cohan suggests that like many films of the 1950s, including George Stevens’ iconic Western Shane (1953) which featured Palance in a similarly memorable and villainous role, Panic in the Streets juxtaposes ‘the breadwinner to a solitary, undomesticated, mysterious male figure who comes to the rescue but is, ultimately, unassimilated because of his toughness’ (Cohan, 1997: 107). Richard Widmark’s family man Dr Clint Reed is set against Paul Douglas’ childless widower Captain Warren; though both men react bitterly to one another at the start of the film, towards the end of the picture they come to respect and ultimately like one another. Widmark had made his first appearance in a feature film as the snivelling, sadistic killer Tommy Udo in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947), and his role as Clint Reed here is the opposite of that character – settled, well-intentioned and selfless. (Interestingly, Reed’s son in this film is named Tommy, and one may wonder whether that is an intentional allusion to Widmark’s first big screen role.) On the other hand, Panic in the Streets offered Jack Palance his role in a feature film, and Palance plays Blackie in a very similar way to which Widmark had essayed Tommy Udo – snarling, sadistic and amoral, prone to fits of rage and motivated purely by selfish greed. (Near to the film’s climax, Reed and Warren corner Blackie as he comes out of Poldi’s second floor bedsit. Blackie is carrying Poldi and, when he sees Reed climbing the stairs towards him, hurls his sick friend at the officials; Poldi falls to what we must assume to be his death.)  The film spends almost as much time focusing on Reed’s home life – his loving relationship with his son, in which Reed feels displaced by a slightly patronising neighbour who has taken a paternal interest in young Tommy; Reed’s terse exchanges with his wife over the household bills and his meagre income – as it does on the search for Blackie and his associates. For his part, Captain Warren regards Reed cynically, believing that Reed is simply intent on furthering his own career: ‘I was assigned to this’, Warren reminds Reed, ‘but let’s not get the idea that I’m a sailor in your navy’. Reed reminds Warren of what he regards as the major difference between them: Reed has a young son, whereas Warren is childless. This, Reed argues, gives him a greater stake in preventing the spread of the plague, explaining his eagerness to prevent the news of Kochak’s death from pneumonic plague from leaking to the press. Warren ‘proves’ himself to Reed when a newspaperman threatens to report news of the plague, and in response Warren has the journalist arrested – despite the reporter’s protests that Warren ‘will be walking the beat if you’re lucky’. In response to the journalist’s threats, Warren comments sombrely to Reed, ‘If I’d been busted by every newspaperman that tried to get my bars, I’d be mopping floors in the Halls of Justice years ago’. As Warren leaves, Reed realises that Warren has come to Reed’s defense at what may become great personal expense, and another detective tells Reed that ‘If that newspaper wanted to put the pressure on him [Warren], he’d be lucky if he could get a job mopping floors’. Following this encounter, Reed returns home and speaks with his wife, reflecting on his working relationship with Warren: ‘You know, today I took a perfectly nice guy, a cop. Not the smartest guy in the world, but who is? So I push him around, make a lot of smart cracks about him and tell him off all day long. He winds up proving he’s four times the man I’ll ever be’, Reed says, ‘Why do I do that? I do the same thing to you, don’t I?’ In response, Nancy tells him to stop following pipedreams: ‘You’re a pretty lucky guy right now’, she says, noting that though the family may be struggling financially, Reed is exactly where he wanted to be when he was a medical student. ‘So every once in a while, you get a guilty feeling, like you’re missing out or that you owe something to me or to Tommy or somebody or other. Then you take it out on whoever’s around [….] So stop feeling sorry for yourself’. The film spends almost as much time focusing on Reed’s home life – his loving relationship with his son, in which Reed feels displaced by a slightly patronising neighbour who has taken a paternal interest in young Tommy; Reed’s terse exchanges with his wife over the household bills and his meagre income – as it does on the search for Blackie and his associates. For his part, Captain Warren regards Reed cynically, believing that Reed is simply intent on furthering his own career: ‘I was assigned to this’, Warren reminds Reed, ‘but let’s not get the idea that I’m a sailor in your navy’. Reed reminds Warren of what he regards as the major difference between them: Reed has a young son, whereas Warren is childless. This, Reed argues, gives him a greater stake in preventing the spread of the plague, explaining his eagerness to prevent the news of Kochak’s death from pneumonic plague from leaking to the press. Warren ‘proves’ himself to Reed when a newspaperman threatens to report news of the plague, and in response Warren has the journalist arrested – despite the reporter’s protests that Warren ‘will be walking the beat if you’re lucky’. In response to the journalist’s threats, Warren comments sombrely to Reed, ‘If I’d been busted by every newspaperman that tried to get my bars, I’d be mopping floors in the Halls of Justice years ago’. As Warren leaves, Reed realises that Warren has come to Reed’s defense at what may become great personal expense, and another detective tells Reed that ‘If that newspaper wanted to put the pressure on him [Warren], he’d be lucky if he could get a job mopping floors’. Following this encounter, Reed returns home and speaks with his wife, reflecting on his working relationship with Warren: ‘You know, today I took a perfectly nice guy, a cop. Not the smartest guy in the world, but who is? So I push him around, make a lot of smart cracks about him and tell him off all day long. He winds up proving he’s four times the man I’ll ever be’, Reed says, ‘Why do I do that? I do the same thing to you, don’t I?’ In response, Nancy tells him to stop following pipedreams: ‘You’re a pretty lucky guy right now’, she says, noting that though the family may be struggling financially, Reed is exactly where he wanted to be when he was a medical student. ‘So every once in a while, you get a guilty feeling, like you’re missing out or that you owe something to me or to Tommy or somebody or other. Then you take it out on whoever’s around [….] So stop feeling sorry for yourself’.

Most protagonists of films noir tend to be childless figures on the margins of society – private investigators like Philip Marlowe in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941), or those drawn into the underworld, such as John Garfield’s boxer Charley Davis in Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (1947). Clint Reed is one of a smaller number of film noir protagonists who, as the narratives of their respective films open, are happily settled in conventional family units and who are not tempted away from their wives by a femme fatale. Invariably, in films noir which feature protagonists who are ‘family men’, the major conflicts in the narrative are precipitated by a threat – real or imaginary – to the family unit. Sometimes this comes from a woman who seduces the male protagonist away from his loving family; sometimes this disruption is more violent. For example, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) opens with a similar depiction of domestic life for its protagonist, Detective Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford), but near the start of that film Bannion’s wife is killed by a bomb, an event which leads Bannion into the underworld on a quest for justice. Most protagonists of films noir tend to be childless figures on the margins of society – private investigators like Philip Marlowe in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941), or those drawn into the underworld, such as John Garfield’s boxer Charley Davis in Robert Rossen’s Body and Soul (1947). Clint Reed is one of a smaller number of film noir protagonists who, as the narratives of their respective films open, are happily settled in conventional family units and who are not tempted away from their wives by a femme fatale. Invariably, in films noir which feature protagonists who are ‘family men’, the major conflicts in the narrative are precipitated by a threat – real or imaginary – to the family unit. Sometimes this comes from a woman who seduces the male protagonist away from his loving family; sometimes this disruption is more violent. For example, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) opens with a similar depiction of domestic life for its protagonist, Detective Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford), but near the start of that film Bannion’s wife is killed by a bomb, an event which leads Bannion into the underworld on a quest for justice.

In Panic in the Streets, the pneumonic plague represents the threat to Reed’s family. Some critics, such as Brenda Murphy, have suggested that within the film, the plague – brought into America by an illegal immigrant from Eastern Europe – acts as a metaphor for Communism (Murphy, cited in Smith, 2014: 267). Murphy has argued that ‘The use of disease and contamination imagery in this film could not be more obvious. Like the mind-disease of Communism as depicted by J. Edgar Hoover, the contamination of the plague spreads instantaneously from person to person without the knowledge or volition of its carriers or victims’ (Murphy, quoted in ibid.). That may (or may not) be stretching the point slightly, but regardless of this Chris Cagle has argued that the initially tense, but latterly friendly, relationship between Reed and Warren is metonymic of broader changes in post-war American society: ‘The relationship between [Reed and Warren] represents allegorically a new political arrangement of the postwar years, [the narrative] pivoting around the moments of conflict and resolution between local authority and the federal government’ (Cagle, 2011: 104). In the film, Reed repeatedly asserts the dangers of the contagion spreading to other cities and states, emphasising the importance of a federal response to the potential for an outbreak. Ultimately, Reed is correct in his assertions – and by the end of the film, Warren is forced to agree with Reed. As a result, Cagle argues that Panic in the Streets ‘rebukes conservative attempts to reel back the New Deal’s strengthened role of the federal government and also challenges the “states rights” platform of 1948’s Dixiecrats’, reinforcing through its narrative ‘a belief that large-scale intervention by the federal government can ameliorate national problems’ (ibid.). By the time that Wild River was made, however, Kazan seemed much more ambivalent about the relationship between federal government and local issues.

Video

Panic in the Streets is uncut, with a running time of 96:10 mins. The 1080p presentation is in the film’s original Academy aspect ratio (1.37:1) and uses the AVC codec; the film takes up just over 21Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. Panic in the Streets is uncut, with a running time of 96:10 mins. The 1080p presentation is in the film’s original Academy aspect ratio (1.37:1) and uses the AVC codec; the film takes up just over 21Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc.

The film’s 35mm monochrome photography is captured very well on this HD release. Along with the use of mise-en-scène, the photography is highly effective in using lighting to underscore the tensions between the demi-monde in which Blackie and his crew operate (and into which Reed and Warren must venture in order to catch their quarry) and the conventional domestic spaces in which Reed and his family live. Reed’s home is lit and photographed in a manner that constructs this domestic space as a space filled with natural light, whereas the warehouses, bars and bedsits through which Blackie and his associates move are lit expressionistically, chiaroscuro low key lighting constructing spaces filled with shadows and threat. Soft, diffuse light is used in the close-ups of Barbara Bel Geddes – presumably a deliberate, artistic choice to depict her character as almost saintly. This presentation represents the film’s photography very well. Contrast levels are very pleasing, midtones being sharply – but not unnaturally – defined, blacks being deep and rich and highlights finely balanced. The image displays no signs of harmful damage – other than a few white flecks and specks. Fine detail is present throughout, offering a clear improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases – including the pleasing R1 DVD release from Fox. Where required – for example, the nighttime scenes of the docks and warehouses, which seem to extend into the horizon – the image has a good sense of depth to it. A solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in an image that has an organic, filmlike texture to it. Compared with, for example, Signal One’s recent Blu-ray release of the roughly contemporaneous Kiss of Death (reviewed by us here), however, the image in this HD presentation of Panic in the Streets is just a hair softer; this is to be expected, of course, in the diffuse light shots of Bel Geddes (for example), but is also noticeable in a few other scenes, suggesting that the master with which Signal One was provided has had some minor – subtly noticeable but not totally destructive – noise reduction algorithm applied to it. This would seem to be commensurate with the reviews of the US Blu-ray release from Twilight Time, suggesting the two releases are from the same source. This is an extremely minor ‘grumble’ though: the Blu-ray presentation of Panic in the Streets is in all respects a huge improvement over the previously-available DVD releases.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is rich and clear, with Alfred Newman’s brass-based main titles theme showing off the range of the track. Some dialogue is a little muted, but this is in keeping with the naturalistic approach Kazan takes towards the subject matter and would seem to be a characteristic of the original sound recording. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are present, and these are easy to read, accurate and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: - A commentary by film noir historians Alain Silver and James Ursini. This seems to be the same commentary that appeared on Fox’s R1 DVD release of the film from about a decade ago. Commentary tracks from Silver and Ursini are always insightful and engaging, and this track is no exception. The pair demonstrate a strong understanding of the film and engage with its relationship with the film noir cycle as a whole, and with Panic in the Street’s relationship with its immediate social context. - Still Gallery. - Trailer. Reversible sleeve artwork is included: the reverse side includes the artwork sans the BBFC logos and barcode.

Overall

An incredibly rich film with a strong sense of texture and place, Panic in the Streets is clearly within the semidocumentary paradigm though has some differences to the most famous semidocumentary films noir – most obviously, the absence of a third-person narrator. The influence of Kazan’s picture, and his association of an outbreak with a manhunt, can be seen in films as diverse as Wolfgang Peterson’s Outbreak (1995) and Herman Yau’s Cat III shocker Ebola Syndrome (1996). In Panic in the Streets, the high drama of the story focusing on the manhunt for Blackie and his crew is offset by naturalistic scenes depicting Reed’s relationship with his wife and son. The pursuit of Blackie ends with an exciting chase through a number of gritty real locations: a coffee warehouse and the wooden supports beneath the docks. An incredibly rich film with a strong sense of texture and place, Panic in the Streets is clearly within the semidocumentary paradigm though has some differences to the most famous semidocumentary films noir – most obviously, the absence of a third-person narrator. The influence of Kazan’s picture, and his association of an outbreak with a manhunt, can be seen in films as diverse as Wolfgang Peterson’s Outbreak (1995) and Herman Yau’s Cat III shocker Ebola Syndrome (1996). In Panic in the Streets, the high drama of the story focusing on the manhunt for Blackie and his crew is offset by naturalistic scenes depicting Reed’s relationship with his wife and son. The pursuit of Blackie ends with an exciting chase through a number of gritty real locations: a coffee warehouse and the wooden supports beneath the docks.

Though Paul Douglas has almost equal screen time to Widmark, the film is largely remembered as the first film in which we saw Palance play the type of snarling, sadistic villain with which he would come to be associated in films such as George Stevens’ Shane (1953). Panic in the Streets also offers Widmark a very different role to that which made him famous (the cruel, sneering Tommy Udo in Kiss of Death). I find it difficult to be objective about this film, as Widmark was my late grandmother’s favourite actor and this was her very favourite film (closely followed by Kiss of Death and Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, 1953); consequently, it’s a film that I grew up watching and is therefore very close to my own heart. It’s an excellent film noir and clearly has a place in the collection of anyone interested in classic films noir. Though not quite as good as the same company’s presentation of Kiss of Death (which, admittedly, is a very high standard to meet: that release was absolutely superb),Signal One’s presentation of Panic in the Streets is very pleasing, a huge improvement over the film’s various DVD releases. This release is an essential purchase for UK fans of film noir. References: Cagle, Chris, 2011: ‘The Postwar Cinematic South: Realism and the Politics of Liberal Consensus’. Barker, Deborah & McKee, Kathryn B (eds), 2011: American Cinema and the Southern Imaginary. The University of Georgia Press: 104-21 Cohan, Steve, 1997: Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties. Indiana University Press Smith, Jeff, 2014: Film Criticism, the Cold War and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. University of California Press

|

|||||

|