|

|

The Film

Tout va bien (Jean-Luc Godard, 1972) Tout va bien (Jean-Luc Godard, 1972)

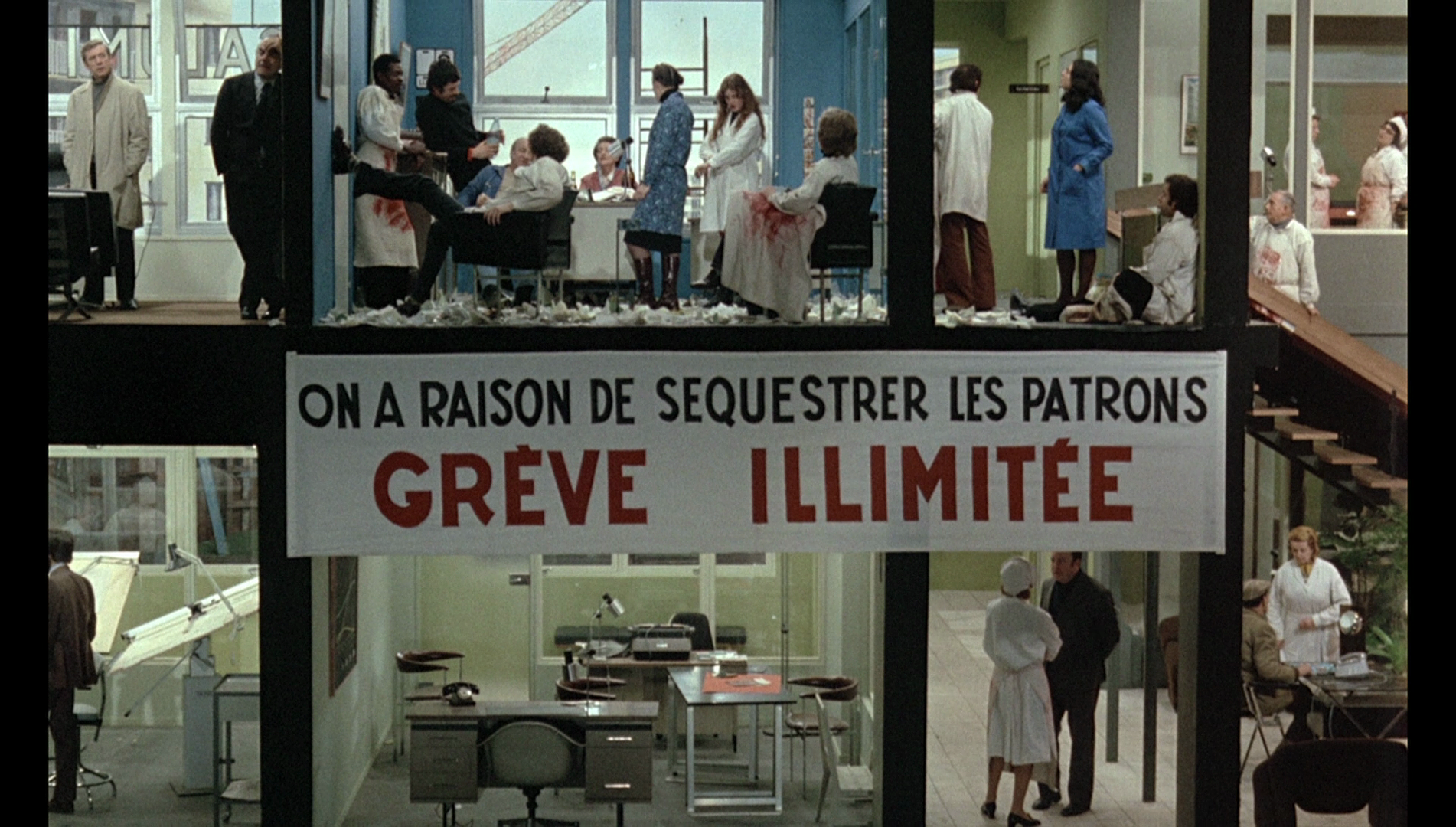

Four years after May 1968, American journalist Susan Dewitt (Jane Fonda), working for the American Broadcasting System, and her husband Jacques (Yves Montand), a director of television commercials, are sent to cover a strike at a butcher’s where the workers have taken their manager, Marco Guidotti (Vittorio Caprioli), hostage. The workers decide to also take Susan and Jacques hostage. Even amongst the protesting workers, however, there is dissent within the ranks: the CGT shop steward criticises the actions of more militant Maoists, which he suggests have put the kibosh on any constructive talks between managers and workers. Meanwhile, Guidotti cannot comprehend the complaints of the workers. Eventually, Susan and Jacques are released, though they disagree in their responses to their captors’ beliefs. Jacques, a former intellectual and radical who has ‘sold out’ and is now making commercials for Dim tights, is chastised by Susan: she tells him that he refuses to ‘live historically’, seeing the private and the public spheres as two separate entities. This disagreement precipitates the end of Susan and Jacques’ relationship, as about them the echoes of May 1968 continue to resonate. Co-directed by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, during Godard’s ‘radical’ phase, Tout va bien also featured Jane Fonda, whose outspoken views on the Vietnam War and the Black Panthers had alienated many Americans; only a couple of months after the release of Tout va bien, Fonda made her (in)famous visit to Vietnam during which she photographed the damage made by US bombing raids to the dams and dykes in North Vietnam, arguing controversially that the USAF had deliberately attempted to destroy the flood control system along the Red River. She was photographed atop an anti-aircraft gun and surrounded by Vietnamese troops during her visit to Hanoi, provoking outrage in America and earning Fonda the nickname ‘Hanoi Jane’; it was an act for which she apologised in 2010, asserting that ‘I will go to my grave regretting the photograph of me in an anti-aircraft gun, which looks like I was trying to shoot at American planes. It hurt so many soldiers. It galvanized such hostility. It was the most horrible thing I could possibly have done. It was just thoughtless’ (Fonda, quoted in Roberts, 2010: np).  Tout va bien deals with the lasting cultural fallout from the protests of May 1968, reminding the film’s audience that those events should not be seen in isolation from what came before and after – that they were part of a continuum of events and cultural attitudes, and the issues that sparked the protests have an ongoing relevance. The film blends fact and fiction, referencing real events (in particular, a brief segue into a eulogy for Gilles Tautin, a young Maoist who on the 10th of June, 1968, dived into the Seine in order to escape from charging gendarmes near the Renault factory in Flins and drowned) and combining them with a fictional narrative. Tout va bien deals with the lasting cultural fallout from the protests of May 1968, reminding the film’s audience that those events should not be seen in isolation from what came before and after – that they were part of a continuum of events and cultural attitudes, and the issues that sparked the protests have an ongoing relevance. The film blends fact and fiction, referencing real events (in particular, a brief segue into a eulogy for Gilles Tautin, a young Maoist who on the 10th of June, 1968, dived into the Seine in order to escape from charging gendarmes near the Renault factory in Flins and drowned) and combining them with a fictional narrative.

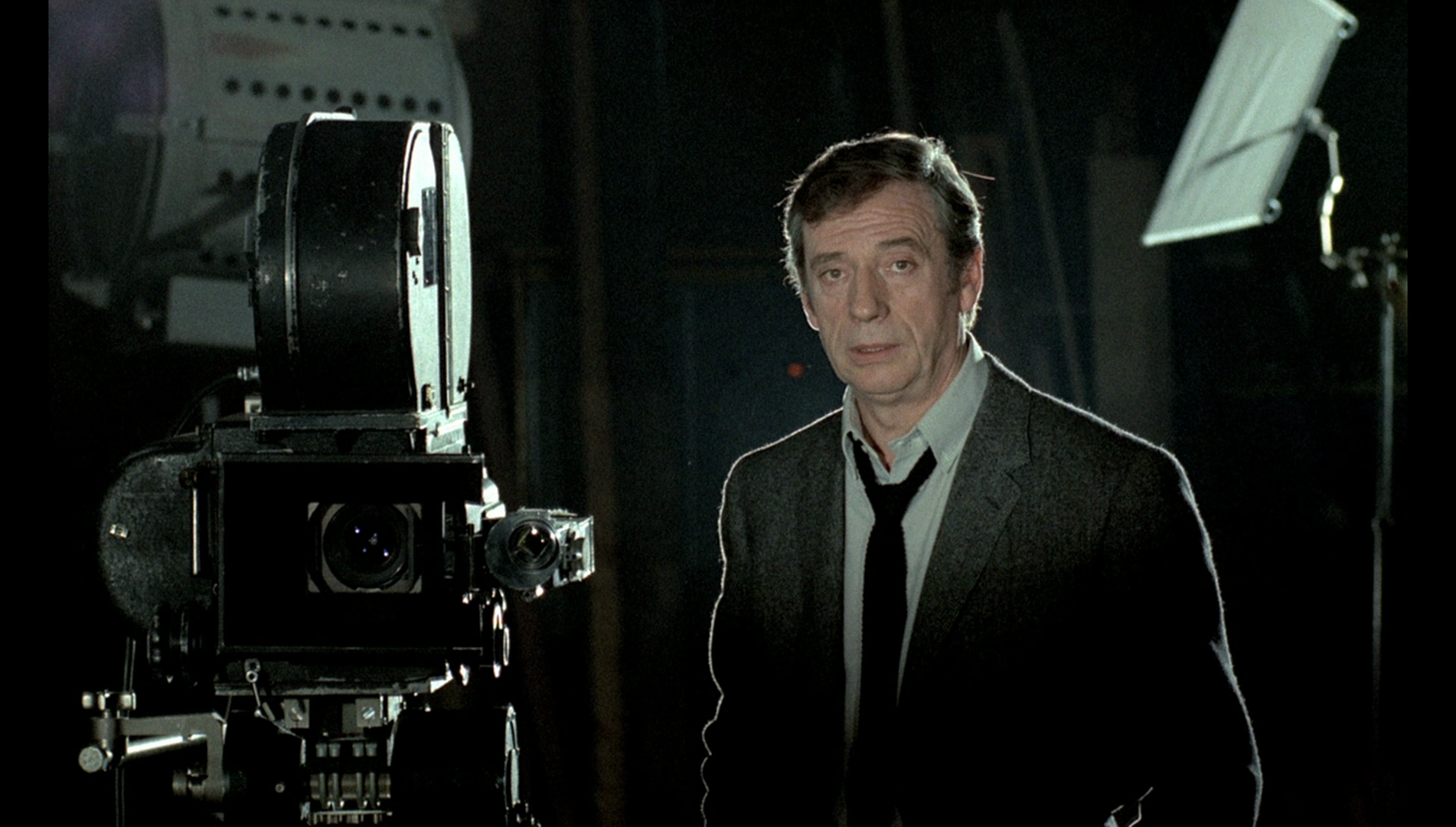

The filmmaking techniques employed by Godard are highly self-reflexive. The film opens with a clapperboard and a male voice announcing scenes and takes. ‘I want to make a film’, a man’s voice, offscreen, asserts. ‘You need money for that’, a woman’s voice, also from offscreen, says, reminding the man that ‘If you use stars, people will give you money’. (This seems to have worked for Tout va bien itself, the presence of Jane Fonda and Yves Montand in the cast securing financing from Gaumont.) Onscreen, the director of the film-within-the-film signs a flurry of cheques in quick succession; the cheques are presented in closeup, and are for various departmental costs involved in the filmmaking process. (Thus the film reminds the viewer that filmmaking itself is a capitalist enterprise.) ‘What will you tell Yves Montand and Jane Fonda?’, the female voice asks, ‘Actors want to see a script before they agree to anything’. ‘There’d be Him and Her’, the male voice responds, ‘and they’d have relationship problems [….] There’d be workers; there’d be farmers’. ‘There’d be petit bourgeois and grand bourgeois’, the female voice adds, ‘And She and He must be placed among them’. At the butcher’s, the huge cutaway set allows the camera to view the happenings on both the ground and first floors of the building; the set here resembles the doll house-like girl’s school in Jerry Lewis’ The Ladies Man (1961). Throughout the picture, characters address the camera directly, in a Brechtian fashion, like interviewees in a documentary. Guidotti speaks in a long monologue, suggesting that ‘Until now, we hadn’t been contaminated by May ’68’, and asking ‘Seriously, what’s “class struggle” got to do with this? You’re still using a 19th Century vocabulary. The glaring injustices of Marx and Engels’ days are over [….] I don’t think the word “revolution” has meaning anymore’. His views are contrasted with a monologue by the CGT shop steward, who reminds the viewer that ‘our salaries haven’t kept up with increased production, and even less with corporate profits [….] The food industry stuffs the bosses and CEOs whilst it underfeeds its workers [….] We need a government of the people which combines the needs of blue-collar workers and white-collar workers, the rural and the urban, believers and non-believers: all those who labour under the stifling conditions of monopolistic capitalism’. In employing this technique of contrasting monologues, the film’s structure sometimes becomes heavily didactic and predicated on a point/counterpoint structure.  Television and the media are associated with the bourgeoisie, part of the system of repression which the workers are reacting against. ‘After building themselves a rat trap’, the offscreen female voice says after Susan and Jacques have been shown in their respective media professions, ‘they’re caught in it themselves and they’re screwed’. The workers restrain Susan and Jacques alongside the manager, drawing an equivalency between the two groups, until Jacques declares that he sympathises with the workers. In a long monologue that takes place in the television studio where Jacques is shooting a commercial for Dim tights, Jacques explains to the film’s audience that he was once a radical filmmaker (and here Godard makes a slight but memorable joke about Truffaut’s adaptation of David Goodis’ Shoot the Piano Player) – he voted with the communists asa ‘reflex’ – but became disenfranchised with the political left following the events of May 1968. Jacques himself delivers a monologue which reflects explicitly on the status of French cinema; Jacques describes himself as ‘a filmmaker who also makes commercials’ and outlines the ‘advertising business’ as ‘pretty stupid and corrupt’. Jacques, it seems, began his career as a screenwriter in the nouvelle vague but became disenfranchised with ‘art’ cinema before May 1968: ‘I was ready for May ’68 to hit me, and that’s what happened’. Faced with the possibility of making a film adaptation of a David Goodis novel, something which he clearly found ridiculous, Jacques decided to retire from filmmaking and retreat into directing commercials. He says he voted with the communists ‘out of reflex [….] But then there was May ’68 and Czechoslovakia. It got to be too much: I couldn’t do it anymore’. Television and the media are associated with the bourgeoisie, part of the system of repression which the workers are reacting against. ‘After building themselves a rat trap’, the offscreen female voice says after Susan and Jacques have been shown in their respective media professions, ‘they’re caught in it themselves and they’re screwed’. The workers restrain Susan and Jacques alongside the manager, drawing an equivalency between the two groups, until Jacques declares that he sympathises with the workers. In a long monologue that takes place in the television studio where Jacques is shooting a commercial for Dim tights, Jacques explains to the film’s audience that he was once a radical filmmaker (and here Godard makes a slight but memorable joke about Truffaut’s adaptation of David Goodis’ Shoot the Piano Player) – he voted with the communists asa ‘reflex’ – but became disenfranchised with the political left following the events of May 1968. Jacques himself delivers a monologue which reflects explicitly on the status of French cinema; Jacques describes himself as ‘a filmmaker who also makes commercials’ and outlines the ‘advertising business’ as ‘pretty stupid and corrupt’. Jacques, it seems, began his career as a screenwriter in the nouvelle vague but became disenfranchised with ‘art’ cinema before May 1968: ‘I was ready for May ’68 to hit me, and that’s what happened’. Faced with the possibility of making a film adaptation of a David Goodis novel, something which he clearly found ridiculous, Jacques decided to retire from filmmaking and retreat into directing commercials. He says he voted with the communists ‘out of reflex [….] But then there was May ’68 and Czechoslovakia. It got to be too much: I couldn’t do it anymore’.

Jacques and Susan argue about their relationship, Jacques asserting that their pattern of behaviour is that he and Susan go to the cinema, watch a movie, return home and fuck. (In the English subtitles, the phrase ‘On baise’ is translated rather timidly as ‘We have sex’.) Susan tells him that this perception of a pattern is precisely the problem with their relationship: for Jacques, their relationship takes place entirely within the private sphere, the phrase ‘On baise’ being disconnected from their other day-to-day activities. Susan reminds her husband that both of their lives feature much more than this: they go to work, where through their labours they produce ideas – represented via articles and commercials – before returning home to fuck. In Jacques’ schema, the body is separated and isolated from the work of the mind and the hands. Jacques’ ‘problem’, according to his wife, is that his vision is of a woman’s hand on an erect penis: he refuses to ‘live historically’. (Here, Godard cuts to an explicit monochrome photograph of precisely this image, which fills the frame for a number of seconds.) For Jacques, their labours are disconnected from their private activities; for Susan, the relationship between these two spheres of activity is essential and cannot be disregarded. Private acts – including sex – must be understood within their social, political and cultural contexts. (Later, alone, Jacques will concede that Susan is right: ‘My problem started when I stopped doing my job as a progressive intellectual’, Jacques asserts.) This fundamental moment of realisation is, the film suggests, responsible for the precipitation of the end of Jacques and Susan’s relationship; the film opens with a shot of Yves Montand and Jane Fonda on a riverbank, an image that represents a conventional romantic ideal. However, at the very end of the picture we are presented with two possible endings, both of which take place in a café: the couple either reunite amicably or split completely. The viewer is left to determine for her/himself which of these endings is ‘preferable’; regardless, the audience is told that ‘We must learn to live historically’ – the unstated epiphany which is reached in the long conversation between Susan and Jacques. The film’s final moments feature an extended dolly shot which documents a derelict area of the city, accompanied on the soundtrack by alternating sounds of rebellion and snippets of cheery pop music; the latter attempts to erase the former, popular culture striving to alienate us from the practice of ‘living historically’, decontextualising its audience and thereby quelling discontent and revolt. (That the dolly shot which allows the camera’s gaze to take in the dereliction of the neighbourhood depicted in this closing sequence mirrors the movement of the camera in the earlier supermarket scene draws an equivalency between dereliction and consumerism – a dereliction of the body politic, perhaps.) Jacques and Susan argue about their relationship, Jacques asserting that their pattern of behaviour is that he and Susan go to the cinema, watch a movie, return home and fuck. (In the English subtitles, the phrase ‘On baise’ is translated rather timidly as ‘We have sex’.) Susan tells him that this perception of a pattern is precisely the problem with their relationship: for Jacques, their relationship takes place entirely within the private sphere, the phrase ‘On baise’ being disconnected from their other day-to-day activities. Susan reminds her husband that both of their lives feature much more than this: they go to work, where through their labours they produce ideas – represented via articles and commercials – before returning home to fuck. In Jacques’ schema, the body is separated and isolated from the work of the mind and the hands. Jacques’ ‘problem’, according to his wife, is that his vision is of a woman’s hand on an erect penis: he refuses to ‘live historically’. (Here, Godard cuts to an explicit monochrome photograph of precisely this image, which fills the frame for a number of seconds.) For Jacques, their labours are disconnected from their private activities; for Susan, the relationship between these two spheres of activity is essential and cannot be disregarded. Private acts – including sex – must be understood within their social, political and cultural contexts. (Later, alone, Jacques will concede that Susan is right: ‘My problem started when I stopped doing my job as a progressive intellectual’, Jacques asserts.) This fundamental moment of realisation is, the film suggests, responsible for the precipitation of the end of Jacques and Susan’s relationship; the film opens with a shot of Yves Montand and Jane Fonda on a riverbank, an image that represents a conventional romantic ideal. However, at the very end of the picture we are presented with two possible endings, both of which take place in a café: the couple either reunite amicably or split completely. The viewer is left to determine for her/himself which of these endings is ‘preferable’; regardless, the audience is told that ‘We must learn to live historically’ – the unstated epiphany which is reached in the long conversation between Susan and Jacques. The film’s final moments feature an extended dolly shot which documents a derelict area of the city, accompanied on the soundtrack by alternating sounds of rebellion and snippets of cheery pop music; the latter attempts to erase the former, popular culture striving to alienate us from the practice of ‘living historically’, decontextualising its audience and thereby quelling discontent and revolt. (That the dolly shot which allows the camera’s gaze to take in the dereliction of the neighbourhood depicted in this closing sequence mirrors the movement of the camera in the earlier supermarket scene draws an equivalency between dereliction and consumerism – a dereliction of the body politic, perhaps.)

Video

Tout va bien is uncut and runs for 95:39 mins. (The graphic monochrome still of a woman’s manicured hand holding an erect penis is presented ‘as is’.) The film is presented in its original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Tout va bien is uncut and runs for 95:39 mins. (The graphic monochrome still of a woman’s manicured hand holding an erect penis is presented ‘as is’.) The film is presented in its original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

An excellent level of fine detail is present throughout the film, resulting in a richly textured presentation that has depth. Colours are reproduced well, skin tones appearing accurate and naturalistic whilst the primary colours Godard employs in various scenes (eg, bright red walls and neon signs) are presented vibrantly, resulting in a lush and expansive palette. Contrast levels are very pleasing and nicely-balanced: deep blacks are offset by richly defined midtones and even highlights. Finally, a pleasing encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 track which contains dialogue mostly in French but with some English lines spoken by Fonda. The French dialogue is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The audio track is free from problems and demonstrates a good sense of depth and range, and the subtitles are easy to read and free from errors. (They sometimes struggle to translate slang, and as noted above they are a little shy in translating the phrase ‘on baise’ as ‘we have sex’, but they’re pretty accurate in terms of capturing the French dialogue.)

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- ‘Letter to Jane: An Investigation About a Still’. This 1972 documentary sees Godard and Gorin narrate (in English) an investigation into a photojournalistic still photograph of Jane Fonda from her trip to Hanoi. The documentary returns time and time again to the photograph, cropping it to underscore the claims made by Godard and Gorin; their analysis of the photograph is supported by cutaways to images from other films. I spend some of my time teaching classes on semiotics, and this documentary is an interesting application of that particular model of analysis, though Gorin and Godard often resort to rhetorical devices to support (or erase) their reasoning. Regardless of one’s feelings vis-à-vis their conclusions, this is certainly a unique piece that speaks of the era in which it was made. - a 1972 interview with Godard (17:56). Godard speaks from the set of Tout va bien about the film’s genesis, its production and its content. - an interview with Jean-Pierre Gorin (27:03). Interviewed in 2004, Gorin reflects on his work with Godard. - the film’s trailer (5:11).

Overall

At the time of its original release, Tout va bien was met with disapproval by mainstream audiences, drawn in by the presences of Fonda and Montand, who found the film perplexing; and by Godard’s more militant audience, who thought Godard had ‘sold out’. At the time, the picture was often compared (unfavourably) with Marin Karmitz’s thematically similar Coup pour coup (also 1972), which gained bonus ‘realism’ points through its use of non-professional actors. The structure of Tout va bien is often intentionally didactic, though both the managers and the workers are united by their belief that the other side deserves a ‘kick up the arse’. At the time of its original release, Tout va bien was met with disapproval by mainstream audiences, drawn in by the presences of Fonda and Montand, who found the film perplexing; and by Godard’s more militant audience, who thought Godard had ‘sold out’. At the time, the picture was often compared (unfavourably) with Marin Karmitz’s thematically similar Coup pour coup (also 1972), which gained bonus ‘realism’ points through its use of non-professional actors. The structure of Tout va bien is often intentionally didactic, though both the managers and the workers are united by their belief that the other side deserves a ‘kick up the arse’.

The film has some extraordinary sequences: most memorable, perhaps, is an alienating slow dolly along the length of a hypermarket’s row of tills and back again, whilst in the background a riot slowly starts following the interjections of a man handing out communist literature. The sequence recalls the opening mobile camerawork of Godard’s previous Week End (1967) but also resembles the remarkable supermarket sequence in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Lieber ist kälter als der Tod (Love is Colder Than Death, 1969, also fairly recently released on Blu-ray by Arrow and reviewed by us here). Ultimately, Tout va bien is a film that is divisive – and intentionally so. What is less divisive, however, is Arrow’s treatment of the picture. The presentation of the main feature is excellent, and the film itself is accompanied by some very good contextual material. References: Roberts, Laura, 2010: ‘Jane Fonda relives her protest days on the set of her new film’. The Telegraph (26 July, 2010)

|

|||||

|