|

|

Blood Feast AKA Egyptian Blood Feast AKA Feast Of Flesh (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (21st October 2017). |

|

The Film

Blood Feast (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1963) Blood Feast (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1963)

Demented caterer Fuad Ramses (Mal Arnold) has, hidden in the backroom of his small store in Miami, a shrine to the Egyptian goddess Ishtar. When he is approached by Mrs Dorothy Fremont (Lyn Bolton) – the mother of Egyptology student Suzette Fremont (Connie Mason) – and asked to arrange a party for Suzette, Ramses seizes the chance to resurrect the ancient rite of the ‘blood feast’: in Ancient Egypt, Ishtar’s worshippers would stage a feast in honour of the goddess, an orgy of bloodshed and cannibalism in which the sect’s priestesses were slaughtered and their flesh and blood consumed, culminating in the goddess’ symbolic embodiment through the high priestess. Ramses is also the author of a specialist tome, Ancient Weird Religious Rites, and he selects those who write to him requesting a copy of his book as his victims – the equivalent of the Ancient Egyptian priestesses who were slaughtered in honour of Ishtar. One by one, Ramses visits his victims and murders them, taking limbs and organs and returning with them to his place of business, Fuad Ramses Exotic Catering, where he crafts these items into the titular ‘blood feast’ in preparation for Suzette’s party.  Suzette’s boyfriend Pete Thornton (William Kerwin) happens to be one of the detectives investigating the murders. Visiting a lecture by an Egyptologist with Suzette, Pete makes a connection between the crimes he has been investigating and the rites associated with Ishtar about which the lecturer speaks; this relationship becomes even more self-evident when one of Ramses’ victims survives and tells the police that her assailant ranted about ‘Itar’. As the ‘blood feast’ (Suzette’s party) nears, the police must work harder to identify the killer and stop him. Suzette’s boyfriend Pete Thornton (William Kerwin) happens to be one of the detectives investigating the murders. Visiting a lecture by an Egyptologist with Suzette, Pete makes a connection between the crimes he has been investigating and the rites associated with Ishtar about which the lecturer speaks; this relationship becomes even more self-evident when one of Ramses’ victims survives and tells the police that her assailant ranted about ‘Itar’. As the ‘blood feast’ (Suzette’s party) nears, the police must work harder to identify the killer and stop him.

Usually acknowledged as the first ‘gore’ film, Herschell Gordon Lewis’ Blood Feast (1963) is an oddball picture. Despite featuring ludicrously over the top gore effects, bizarre acting and slapdash photography (and therefore impossible to take seriously), the film nevertheless ended up on the ‘video nasties’ list in the UK when Astra released the uncut version of Blood Feast on videocassette. Subsequently, the film was unavailable in the UK until 2001, when Tartan Video submitted the picture to the BBFC and it was passed with 23 seconds of cuts, which the BBFC suggested were simply owing to the fact that the film had been successfully prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act as recently as 1994. (When resubmitted in 2005, however, Blood Feast was finally passed uncut – over 40 years after its production.) Lewis teamed up with producer David Friedman, their partnership exploiting Lewis’ prior experience of making industrial films and commercials and Friedman’s expertise as a ‘huckster’. Lewis and Friedman worked with an outline of between 14 and 24 pages in length, hammering together a script on a portable typewriter during a flight from Chicago to Miami (see Konow, 2012: 93). They scored a coup in the casting of former Playmate of the Year, Connie Mason, though Mason’s contract with Playboy forbade her from appearing nude in the picture (ibid.: 94)  The narrative of Blood Feast is little more than a thread from which the film’s various gory setpieces hang precariously. Lewis frequently resisted any attempt to intellectualise Blood Feast, arguing that the picture was an economic exercise with no artistic pretensions whatsoever: in interview, he asserted that ‘I’m the kind of jerk who sits in the theater watching the audience, and if they react, that’s all I care about. I don’t care about someone who is writing l’histoire du cinema, attributing motivations that aren’t there’ (Lewis, quoted in Konow, op cit.: 93). However, regardless of the intentions of Lewis, Blood Feast has a strangely Brechtian quality that is carried through its application of crude filmmaking techniques. Dialogue is risible (‘Well, we’re just working with a homicidal maniac, that’s all’, Pete observes near the start of the film before adding, ‘Well, Frank, looks like one of those long, hard ones’). Narrative threads are introduced but not expanded upon: when Dorothy Fremont approaches Fuad Ramses and asks him to cater for Suzette’s party, the film suggests Ramses has some sort of hypnotic power, implanting into Dorothy Fremont’s mind the suggestion that she should ask Ramses to produce an Egyptian feast. (‘Have you ever had an… Egyptian feast?’, he asks dramatically, as a musical ‘sting’ appears on the soundtrack.) However, this theme is never revisited. The film’s narrative grinds to a halt for its moments of bloody mayhem (including eyes gouged out, tongues ripped from open mouths, limbs hacked off, brains scooped out). Onscreen newspaper headlines describe these crimes brutally, reinforcing just how gruesome they are: ‘Legs Cut Off’ screams one particular headline. Perhaps even more pointedly, the once-novelty of Lewis’ refusal to cut away from the film’s moments of violence perhaps seems more ludicrous today than shocking owing to the crudity of the film’s visual effects. Performances are equally Brechtian, Connie Mason’s flat performance as Suzette clashing with the deadpan sincerity of Mal Arnold’s performance as Fuad Ramses: the solemnity of Ramses’ ‘Ancient Weird Religious Rites’ is placed in juxtaposition with the kitsch 1960s setting, resulting in an almost Brechtian distanciation effect – regardless of whether or not this was Lewis’ intention. Lewis even has the gall to appear in the picture as the voice of the radio announcer who reads out details of the murders. The narrative of Blood Feast is little more than a thread from which the film’s various gory setpieces hang precariously. Lewis frequently resisted any attempt to intellectualise Blood Feast, arguing that the picture was an economic exercise with no artistic pretensions whatsoever: in interview, he asserted that ‘I’m the kind of jerk who sits in the theater watching the audience, and if they react, that’s all I care about. I don’t care about someone who is writing l’histoire du cinema, attributing motivations that aren’t there’ (Lewis, quoted in Konow, op cit.: 93). However, regardless of the intentions of Lewis, Blood Feast has a strangely Brechtian quality that is carried through its application of crude filmmaking techniques. Dialogue is risible (‘Well, we’re just working with a homicidal maniac, that’s all’, Pete observes near the start of the film before adding, ‘Well, Frank, looks like one of those long, hard ones’). Narrative threads are introduced but not expanded upon: when Dorothy Fremont approaches Fuad Ramses and asks him to cater for Suzette’s party, the film suggests Ramses has some sort of hypnotic power, implanting into Dorothy Fremont’s mind the suggestion that she should ask Ramses to produce an Egyptian feast. (‘Have you ever had an… Egyptian feast?’, he asks dramatically, as a musical ‘sting’ appears on the soundtrack.) However, this theme is never revisited. The film’s narrative grinds to a halt for its moments of bloody mayhem (including eyes gouged out, tongues ripped from open mouths, limbs hacked off, brains scooped out). Onscreen newspaper headlines describe these crimes brutally, reinforcing just how gruesome they are: ‘Legs Cut Off’ screams one particular headline. Perhaps even more pointedly, the once-novelty of Lewis’ refusal to cut away from the film’s moments of violence perhaps seems more ludicrous today than shocking owing to the crudity of the film’s visual effects. Performances are equally Brechtian, Connie Mason’s flat performance as Suzette clashing with the deadpan sincerity of Mal Arnold’s performance as Fuad Ramses: the solemnity of Ramses’ ‘Ancient Weird Religious Rites’ is placed in juxtaposition with the kitsch 1960s setting, resulting in an almost Brechtian distanciation effect – regardless of whether or not this was Lewis’ intention. Lewis even has the gall to appear in the picture as the voice of the radio announcer who reads out details of the murders.

One of the film’s most audacious moments features Ramses attacking a young couple, Marcy (Ashlyn Martin) and Tony (Gene Courtier), as they kiss on the beach. Ramses lunges out of the darkness and hacks Marcy’s brains out of her skull, allowing them to run through his fingers. Lewis punctuates this moment with a close-up of the top of Marcy’s head, her skull caked in grue, and cleverly dissolves from this bloody image to the flashing red light of a police car. The whole enterprise ends with a bizarre one-liner whose delivery is as deadpan as the presentation of the gore sequences.

Blood Feast is here paired with Lewis’ Scum of the Earth, released the same year (in 1963) and responsible for kickstarting another subgenre: the ‘roughie’. Blood Feast is here paired with Lewis’ Scum of the Earth, released the same year (in 1963) and responsible for kickstarting another subgenre: the ‘roughie’.

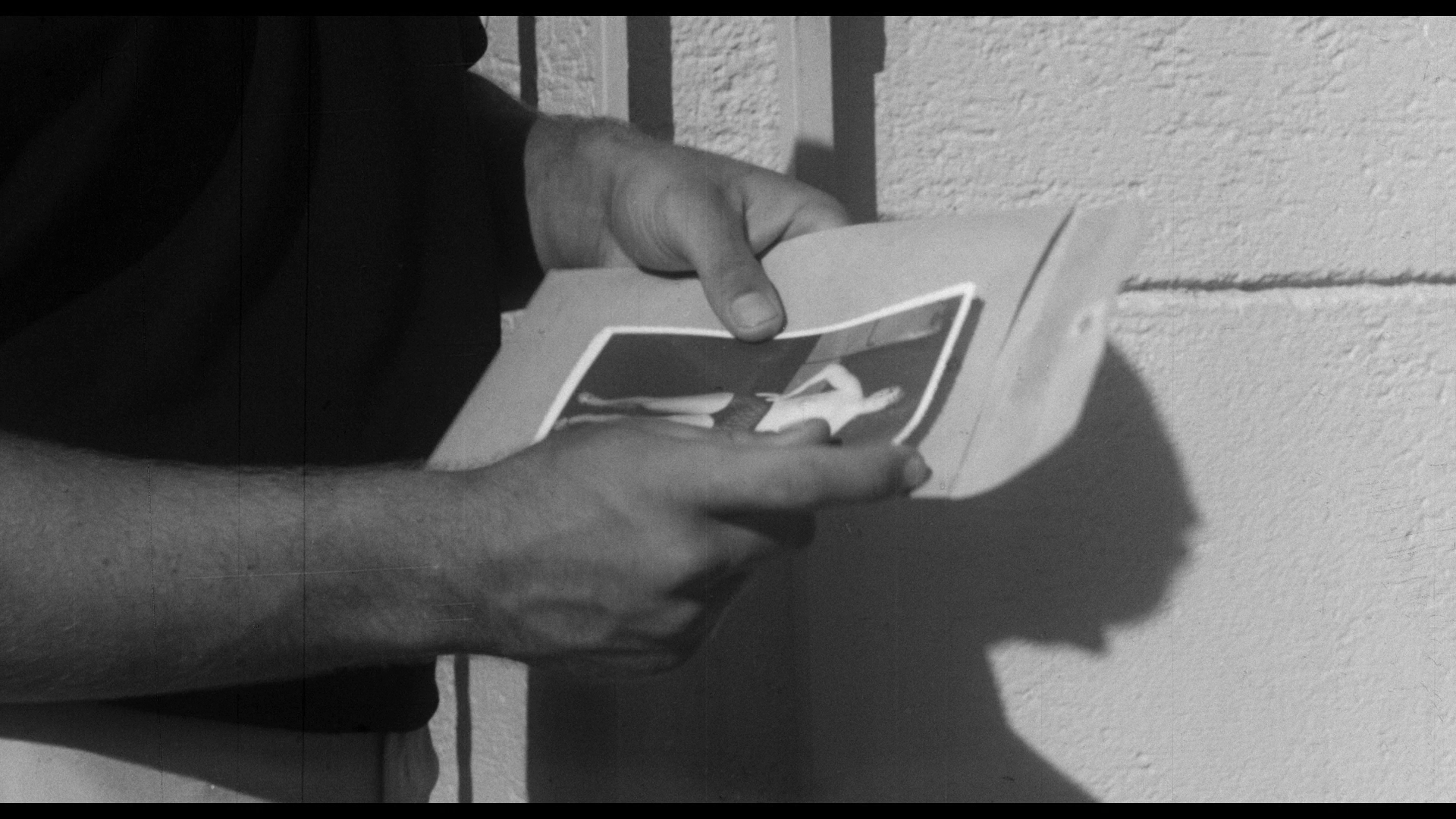

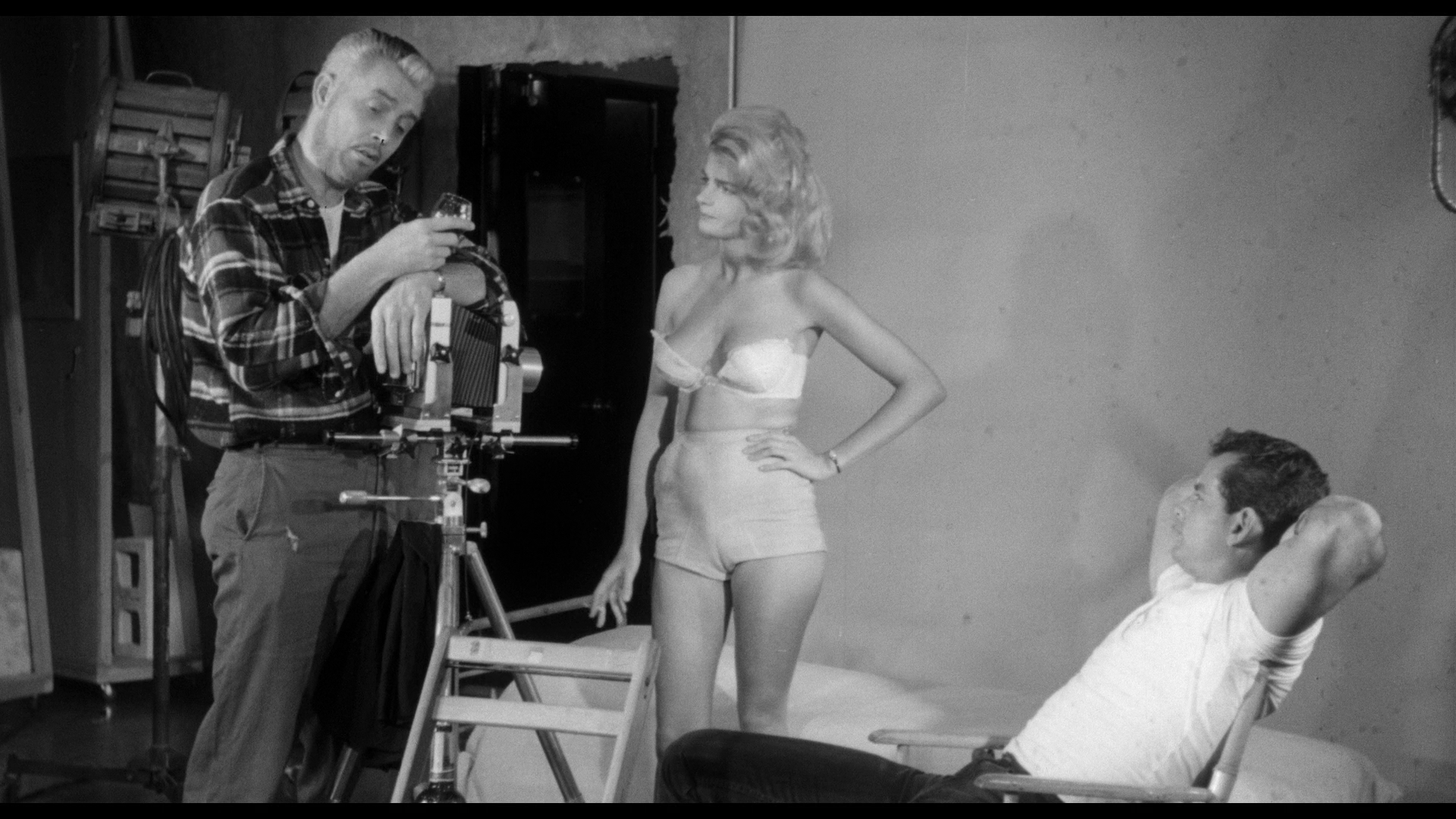

Scum of the Earth features William Kerwin again, this time as Harmon, a photographer working for a sleazy pornographer named Lang (Lawrence J Aberwood). Lang forces Harmon to work with creepy youth Larry (Mal Arnold, again – 30 at the time of the film’s release, despite the fact that his character claims in the film’s dialogue to be a minor) and thuggish brute Ajax (Craig Maudsley Jr). Harmon’s work involves promising the earth to young women in order to persuade them to pose nude in his studio, before Lang blackmails them with prints of these images (threatening to send them to family and friends) in order to ‘up the ante’, demanding that the young women pose in ever more explicit scenarios – including being raped by Ajax. Prints of the photographs are then sold on the street by Larry, seemingly in and around the university campus. Lang promises seasoned model Sandy (Sandra Sinclair) her ‘freedom’ if she can persuade another young woman to pose for Harmon. Sandra chooses as her ‘victim’ Kim Sherwood (Vickie Miles), an innocent girl who, when presented with the chance of earning money as a model, sees it as an opportunity to save enough funds to pay for her university tuition. Harmon and his crew are tasked with ‘turning out’ young Kim. However, Harmon becomes increasingly sympathetic towards the innocent and naïve Kim. Scum of the Earth depicts a seedy group of pornographers, headed by Lang, who knowingly exploit young women through blackmail into posing naked for smutty photographs that end up being sold on the streets as if they were smack. To this end, the film features some lurid dialogue (‘Our business is pleasure. Let’s do it in front of the camera’, Lang notes; ‘Well, I’m willing if she is’, Larry leers in response). The world of these pornographers is depicted without moral counterpoint: unlike Blood Feast, Scum of the Earth doesn’t balance the scenes depicting its criminals with scenes featuring the police – or some other agency of law and morality – pursuing them. However, the picture does make an attempt to explore the motivations of the pornographers: in one very memorable scene, Lang attempts to persuade Kim into posing for ever more explicit photographs. He tries to tease her into co-operating via offering to pay for her university tuition. Kim resists. In response, Lang begins a long, angry rant – the strength of Lang’s convictions conveyed through a tight close-up of Lang’s mouth as he speaks – which suggests that his motivations are deeply pathological: the monologue culminates in Lang’s angry declaration that ‘All you kids make me sick! You act like little Miss Muffet and down inside you're dirty, do you hear me? Dirty! You're greedy and self-centred and think you can get away with anything. You're no better than the girl who sells herself to a man; you're worse because you're a hypocrite. And now little Miss Muffet is in trouble and she's all outraged virtue. Well, you listen, and you listen well. You’re damaged merchandise, and this is a fire sale’. (The final sentences of this monologue will be familiar to anyone who remembers Something Weird’s opener.)  Like many other ‘roughies’, Scum of the Earth attempts to have its cake and eat it. Its criticism of the dank world of pornographers is mealy-mouthed, the narrative premise allowing Lewis to criticise Lang and his compadres whilst also revelling in opportunities to depict nudity. (The film features some surprisingly stark moments of nudity, including one brief full-frontal shot.) In one specific scene, Kim is tricked by Harmon and Larry into posing with her breasts exposed, believing that Harmon’s large format studio camera will capture only her topless torso and not her face – until, that is, Larry bursts into the studio with a snazzy Speed Graphic with mounted flash and uses it to take a full-figure photograph of Kim with which she will later be blackmailed by Lang. (Incidentally, for lovers of photography the film features a wonderful array of vintage equipment, including Larry’s Speed Graphic, Harmon’s large format plate camera and studio lights, and Harmon’s analogue light metre.) In this scene and elsewhere, Scum of the Earth criticises the pornographers whilst also seizing the opportunity to feature prominently the bare breasts of the actress playing Kim. The whole picture builds up to a final scene in which the filmmakers attempt to offer explicit judgement about the seedy netherworld depicted within the story via the use of an intrusive voiceover. Comparisons may be drawn between the film and examples of written pornography of the 18th and 19th Centuries, in which writers would often use a framing device which suggested that the story was either based on true events or was a ‘found’ document, thereby distancing the author from their text and allowing them to deliver for their audience a narrative which both criticised and sensationalised the sexual exploitation of young women (which was the most common narrative paradigm of this type of literature). Examples of this trend include, of course, Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722) and John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748). Like many other ‘roughies’, Scum of the Earth attempts to have its cake and eat it. Its criticism of the dank world of pornographers is mealy-mouthed, the narrative premise allowing Lewis to criticise Lang and his compadres whilst also revelling in opportunities to depict nudity. (The film features some surprisingly stark moments of nudity, including one brief full-frontal shot.) In one specific scene, Kim is tricked by Harmon and Larry into posing with her breasts exposed, believing that Harmon’s large format studio camera will capture only her topless torso and not her face – until, that is, Larry bursts into the studio with a snazzy Speed Graphic with mounted flash and uses it to take a full-figure photograph of Kim with which she will later be blackmailed by Lang. (Incidentally, for lovers of photography the film features a wonderful array of vintage equipment, including Larry’s Speed Graphic, Harmon’s large format plate camera and studio lights, and Harmon’s analogue light metre.) In this scene and elsewhere, Scum of the Earth criticises the pornographers whilst also seizing the opportunity to feature prominently the bare breasts of the actress playing Kim. The whole picture builds up to a final scene in which the filmmakers attempt to offer explicit judgement about the seedy netherworld depicted within the story via the use of an intrusive voiceover. Comparisons may be drawn between the film and examples of written pornography of the 18th and 19th Centuries, in which writers would often use a framing device which suggested that the story was either based on true events or was a ‘found’ document, thereby distancing the author from their text and allowing them to deliver for their audience a narrative which both criticised and sensationalised the sexual exploitation of young women (which was the most common narrative paradigm of this type of literature). Examples of this trend include, of course, Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722) and John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748).

Video

Blood Feast takes up 16.6Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc and is uncut, with a running time of 67:11 mins. Scum of the Earth runs a little longer, at 75:28 mins, and takes up 17Gb. Both films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. Blood Feast takes up 16.6Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc and is uncut, with a running time of 67:11 mins. Scum of the Earth runs a little longer, at 75:28 mins, and takes up 17Gb. Both films are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec.

Both films are, somewhat controversially, presented in the 1.85:1 ratio (though the credits for Blood Feast are presented at 1.33:1). Arrow’s ‘Box of Blood’ release of H G Lewis’ films contained additional discs which featured alternative open-matte 1.33:1 presentations of many, but not all, of the films included in that boxed set – including Blood Feast and Scum of the Earth. Where some of Lewis’ other films look awkward when presented in the 1.85:1 ratio (most notably 2000 Maniacs and Color Me Blood Red, 1965), the compositions within Blood Feast look fine at 1.85:1. The photography in Blood Feast is lackadaisical. In some scenes, shallow depth of field is utilised but the area of focus is beyond what should be the focus point. This is noticeable in a few of the closeups featuring gore effects: the lens is focused on an object beyond the handfuls of grue that Ramses thrusts into the camera, with the result that the actual subject of the shot is slightly out of focus. With this in mind, however, Blood Feast looks very good on this Blu-ray release. A strong level of fine detail is present throughout the film. Minimal damage is present, though some scenes feature noticeable vertical scratches in the emulsions and in a handful of shots during the final sequence there’s an odd pulsing effect to the right of the screen that looks like an issue with how the negative was processed (it’s the kind of effect that’s noticeable when the film isn’t loaded onto the developing spools properly). Contrast levels are very good, with defined midtones and good gradation to deepest black. Colours are rich and vibrant, the tomato red of the fake blood being communicated with gusto and as unreal as it should be. Finally, a solid encode ensures the film retains the structure of 35mm film.  With regards the aspect ratio controversy noted above, Scum of the Earth looks a little more awkward at 1.85:1, the compositions often feeling very cramped along the vertical axis and unbalanced; but then, the photography in this picture is, the scenes set in Harmon’s studio aside, largely quite rough and ready. The 35mm monochrome photography is crisp and displays good fine detail, though there are a handful of shots that seem very soft, almost as if they have been patched in from an inferior source. Contrast levels are good, with strong midtones and balanced highlights being complemented by rich blacks. A number of scenes display an instability in the emulsions, resulting in a slight ‘throbbing’ appearance onscreen. Scratches, blotches and vertical lines suggesting both damage to a negative and positive source (ie, white and black) are present throughout, with some scenes featuring quite heavy damage in this way. Finally, the structure of 35mm film is present though is muted in some specific scenes. It’s a watchable presentation, certainly better than the DVD format offers, and the damage on display is entirely photochemical – giving an experience comparable to watching a vintage 35mm print. With regards the aspect ratio controversy noted above, Scum of the Earth looks a little more awkward at 1.85:1, the compositions often feeling very cramped along the vertical axis and unbalanced; but then, the photography in this picture is, the scenes set in Harmon’s studio aside, largely quite rough and ready. The 35mm monochrome photography is crisp and displays good fine detail, though there are a handful of shots that seem very soft, almost as if they have been patched in from an inferior source. Contrast levels are good, with strong midtones and balanced highlights being complemented by rich blacks. A number of scenes display an instability in the emulsions, resulting in a slight ‘throbbing’ appearance onscreen. Scratches, blotches and vertical lines suggesting both damage to a negative and positive source (ie, white and black) are present throughout, with some scenes featuring quite heavy damage in this way. Finally, the structure of 35mm film is present though is muted in some specific scenes. It’s a watchable presentation, certainly better than the DVD format offers, and the damage on display is entirely photochemical – giving an experience comparable to watching a vintage 35mm print.

Scum of the Earth:

Blood Feast:

Audio

Both films are presented with LPCM 1.0 soundtracks. In the case of Blood Feast, this audio track is clear and with good range though evidences some hiss and crackle. Scum of the Earth features more prominent distortion and more frequent examples of pops and crackle, but the dialogue is always audible. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are available for both features; these are easy to read, accurate and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes a veritable feast (geddit?) of contextual material, including: The disc includes a veritable feast (geddit?) of contextual material, including:

- Optional introductions to both features by Lewis (1:32 and 1:11), in which Lewis highlights how both films were the first of their respective kind (the gore picture, in the case of Blood Feast; and the ‘roughie’, in the case of Scum of the Earth). - ‘Blood Perspectives’ (10:54). Filmmakers Nicholas McCarthy and Rodney Ascher discuss the impact of Blood Feast on their own careers. Both explore their relationship with Blood Feast and, more generally, Lewis’ work, Ascher noting that one of the things that interests him about the films is how they function as ‘accidental documentaries’. - ‘Herschell’s History’ (5:18). Recorded in 2007, this interview with Lewis sees the director discussing his transition from teaching to the world of commerce, and finally on to a career as a filmmaker. - ‘How Herschell Found His Niche’ (7:15). In a new interview, Lewis talks about his work making ‘nudie cuties’. - ‘Carving Magic’ (20:31). This wonderful ‘industrial’ film from 1959, directed by Lewis, features William Kerwin and comedian Harvey Korman as two men who attempt to demonstrate to their wives the fine art of carving meat for the dinner table.

- Archival interview with Lewis and Friedman (18:28). Recorded in 1987, this interview with Lewis and Friedman represented the first time in many years that the pair had conversed with one another. - Blood Feast outtakes (45:55). These silent snippets of unused footage from the production of Blood Feast, accompanied on the audio track by cues from Lewis’ score for the picture, are reputedly pretty much everything that was shot other than the footage used in the completed feature. - Scum of the Earth ‘clean’ scenes (4:36). Taken from an SD source, these are alternate ‘covered’ versions of some of the scenes which in the main feature include nudity. - Promotional gallery that contains: the trailer for Blood Feast (2:23); a radio spot for the same feature (1:02); Blood Feast theatre announcement (0:59); and trailers for three of Lewis’ ‘nudie cutie’ films, The Adventures of Lucky Pierre (1:46), Three Bares (2:15) and Bell, Bare, and Beautiful (1:32). - An audio commentary for Blood Feast by Lewis, Friedman and Mike Vraney. This is the same commentary track that was included on Something Weird’s DVD release of Blood Feast and features Lewis and Friedman offering vivid recollections of the film’s genesis, its production and its lasting legacy.

Overall

On a technical level, much of Blood Feast is risible: flat staging is complemented by stilted performances, oddball dialogue and lackadaisical photography. However, the film ‘works’ regardless of these elements. Lewis once asserted that Blood Feast ‘is like a Walt Whitman poem. It’s no good but it’s the first of its kind’ (Lewis, quoted in Szczesiul, 2017: 170). Fuad Ramses’ quasi-supernatural motivation for his crimes and the film’s insistence on ‘punishing’ young women for their displays of sexuality became defining paradigms of the later ‘slasher’ pictures of the late 1970s and 1980s (for example, Sean S Cunningham’s Friday the 13th, 1980, and Tony Maylam’s The Burning, 1981). As a breakthrough in the evolution of screen grue, the picture is a landmark, and as a viewing experience – whether or not one approaches it ironically – it’s an entertaining picture. Some of Lewis’ later films, including Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), featured a more developed approach to narrative with stronger motivation for their gory setpieces and are therefore arguably ‘better’ films. On a technical level, much of Blood Feast is risible: flat staging is complemented by stilted performances, oddball dialogue and lackadaisical photography. However, the film ‘works’ regardless of these elements. Lewis once asserted that Blood Feast ‘is like a Walt Whitman poem. It’s no good but it’s the first of its kind’ (Lewis, quoted in Szczesiul, 2017: 170). Fuad Ramses’ quasi-supernatural motivation for his crimes and the film’s insistence on ‘punishing’ young women for their displays of sexuality became defining paradigms of the later ‘slasher’ pictures of the late 1970s and 1980s (for example, Sean S Cunningham’s Friday the 13th, 1980, and Tony Maylam’s The Burning, 1981). As a breakthrough in the evolution of screen grue, the picture is a landmark, and as a viewing experience – whether or not one approaches it ironically – it’s an entertaining picture. Some of Lewis’ later films, including Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), featured a more developed approach to narrative with stronger motivation for their gory setpieces and are therefore arguably ‘better’ films.

Arrow’s presentation of Blood Feast is very pleasing. Unlike some of Lewis’ later films, the picture isn’t compromised by the 1.85:1 framing, and in all other respects the video presentation is impressive. The film is also accompanied by some excellent contextual material. References: Konow, David, 2012: Reel Terror: The Scary, Bloody, Gory, Hundred-Year History of Classic Horror Films. New York: Thomas Dunne Books Szczesiul, Anthony, 2017: The Southern Hospitality Myth: Ethics, Politics, Race, and American Memory. The University of Georgia Press Blood Feast:

Scum of the Earth:

|

|||||

|