|

|

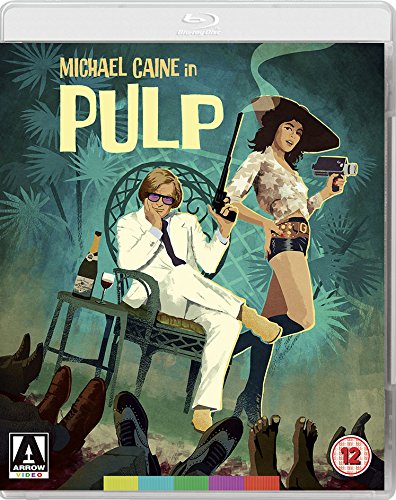

Pulp (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd January 2018). |

|

The Film

Pulp (Mike Hodges, 1972) Pulp (Mike Hodges, 1972)

Chester Thomas King, known as ‘Mickey’ King (Michael Caine), is a former undertaker who abandoned his career, wife and children in order to fulfil his dream of becoming a writer. The trouble is, Mickey doesn’t like writing very much. Nevertheless, he has made a sustainable, if not lucrative, career writing lurid crime novels under equally lurid pseudonyms. Mickey is asked by his publisher, Milo Marcovic (Leopoldo Trieste), to accept a commission: Mickey is requested by the intimidating, thug-like Dinuccio (Lionel Stander) to act as ghostwriter on an autobiography of a mystery celebrity for whom Dinuccio acts as a public relations agent. Mickey reluctantly agrees, and Dinuccio tells Mickey to take a coach journey south; Mickey will be contacted along the way. On the coach, Mickey converses with Jake Miller (Al Lettieri), who presents himself as a fan of Mickey’s work. Mickey believes Jake to be his contact with Dinuccio’s celebrity client. Mickey and Jake spend the night in the same hotel, the Hotel Albert, though there is a mix-up with the rooms and Mickey finds himself sleeping in the room booked for Jake, Jake spending the night in the room booked for Mickey. During the night, Mickey visits Jake and finds Jake’s dead body in the bathtub. Mickey surmises that he was the intended target and Jake was killed by mistake. In the morning, Mickey makes the acquaintance of an eccentric Englishman (Dennis Price) who is fond of quoting Lewis Carroll. Meanwhile, Jake’s body seems to have disappeared: the police haven’t been called, and there is no trace of Jake’s presence in his hotel room.  At a historical site, Mickey encounters a young American woman, Liz (Nadia Cassini). Liz reveals herself to be Mickey’s contact with Dinuccio’s client. She reveals that the celebrity whose autobiography Mickey has been commissioned to ghostwrite is Preston Gilbert (Mickey Rooney). Gilbert is a former Hollywood actor who is living in exile owing to his associations with the mob. At a historical site, Mickey encounters a young American woman, Liz (Nadia Cassini). Liz reveals herself to be Mickey’s contact with Dinuccio’s client. She reveals that the celebrity whose autobiography Mickey has been commissioned to ghostwrite is Preston Gilbert (Mickey Rooney). Gilbert is a former Hollywood actor who is living in exile owing to his associations with the mob.

Gilbert tells Mickey that his life has been threatened. A week later, Mickey has completed the book and Gilbert throws a party where Mickey meets Gilbert’s flirtatious former wife Betty (Lizabeth Scott). Betty is now married to Prince Cippola (Victor Mercieca), a fascist whose right wing politics are rapidly gaining popularity. At the party, Gilbert announces that he’s been diagnosed with cancer, though those gathered around him believe this is just another of Gilbert’s practical jokes. Shots ring out; Mickey is shot and killed by an assassin dressed as a priest. A witness to the murder, Mickey is asked to identify the assailant in a line-up of priests. When he returns to Gilbert’s island home, Mickey is told by Dinuccio that Gilbert was killed over a secret from his past: the killer didn’t want this secret to be revealed in Gilbert’s planned autobiography. Mickey investigates and discovers the truth of the secret buried in Gilbert’s past: Gilbert had been associated with Prince Cippola, and the pair had held secret orgies during which a girl, Silvana Lepri, had died. Gilbert and Cippola had dumped Lepri’s body on a beach, and owing to their influence, the case had never been investigated. Director Mike Hodges has said that Pulp was inspired by his love of 1950s ‘B’ movies, an enthusiasm which developed concomitant with Hodges’ growing fascination with the work of hardboiled authors such as Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Mickey Spillane and James M Cain (Hodges, 2017: np). Following the success of Hodges’ previous film Get Carter (1971), itself an adaptation of a hardboiled novel by the English writer Ted Lewis, Hodges was asked to make another film with star Michael Caine and producer Michael Klinger. Hodges responded by writing Pulp on spec, and the script, originally titled ‘Memoirs of a Ghost Writer’, was received warmly by both Klinger and Caine (ibid.). Hodges wanted to shoot the picture in Italy but became frustrated at the realisation that the locations he desired would, he was told by the Italian production manager, necessitate a ‘protection fee’ to be paid to the local Mafia (Hodges, op cit.). Instead, Hodges made the decision to shoot the film in Malta.  Hodges 1970 television play ‘Rumour’, made for ITV’s ITV Playhouse strand (and released on DVD by Network in 2009, reviewed by us here), had featured a film noir-style hardboiled voiceover narration by what Hodges has called ‘a Walter Winchell replicant’; the use of this narration was laced with irony, Hodges highlighting the ‘discrepancy between what he was reporting and what the viewer was seeing’ (Hodges, op cit.). When writing Pulp, Hodges decided to use a similar device, and the completed film is dominated by narration from Michael Caine’s character, Mickey King; it’s a narration that contains irony in King’s appropriation of the hardboiled style of the novels he writes, which is placed in juxtaposition with King’s own ordinary background (as a divorced former undertaker). This contrast between the buttoned-up, banal background of King and the hardboiled stylings of both his narration and the world in which he finds himself invites comparisons with Stephen Frears’ Gumshoe (released the year before, in 1971), in which Albert Finney essayed a Liverpudlian bingo caller and stand-up comic who finds himself involved in a Sam Spade-style plot. Hodges 1970 television play ‘Rumour’, made for ITV’s ITV Playhouse strand (and released on DVD by Network in 2009, reviewed by us here), had featured a film noir-style hardboiled voiceover narration by what Hodges has called ‘a Walter Winchell replicant’; the use of this narration was laced with irony, Hodges highlighting the ‘discrepancy between what he was reporting and what the viewer was seeing’ (Hodges, op cit.). When writing Pulp, Hodges decided to use a similar device, and the completed film is dominated by narration from Michael Caine’s character, Mickey King; it’s a narration that contains irony in King’s appropriation of the hardboiled style of the novels he writes, which is placed in juxtaposition with King’s own ordinary background (as a divorced former undertaker). This contrast between the buttoned-up, banal background of King and the hardboiled stylings of both his narration and the world in which he finds himself invites comparisons with Stephen Frears’ Gumshoe (released the year before, in 1971), in which Albert Finney essayed a Liverpudlian bingo caller and stand-up comic who finds himself involved in a Sam Spade-style plot.

Hodges was also inspired by the political situation in Italy, with the revelation in then-recent elections that there was growing support for the fascist party (Hodges, op cit.). Hodges found this ‘barely believable’, questioning ‘Can it be a mere 15 years after the war that this malignant ideology re-emerged?’ (ibid.). Hodges later suggested the picture anticipated the resurfacing of far right ideology within European politics, with the appearance of figures like Silvio Berlusconi and Marine Le Pen (Hodges, in Davies, 2002). Hodges decided to marry this source of inspiration to a story about another Italian institution, the Cosa Nostra. Finding ‘Mussolini and Italian fascism close to comic opera’ and feeling that their ‘uniforms and strutting were comedic not sinister’, Hodges discovered his approach ‘shifted to satire; more Fellini than Bertolucci’ (Hodges, op cit.). In fact, the island home of Preston Gilbert – which comes under threat from outside forces – and the presence within the cast of Lionel Stander underscore Pulp’s similarities with another black comedy produced by Michael Klinger, Roman Polanski’s Cul-de-sac (1966).  Further to this, Pulp’s narrative drew on the story of Wilma Montesi, a 21 year old woman whose dead body was found on a beach near Torvajanica in 1953, contradictory information given about the case and about the circumstances of her death leading to a widespread suggestion that some sort of conspiracy was at play and the authorities were attempting a ‘cover-up’. Notorious playboy Ugo Montagna and Piero Piccioni, the son of vice prime minister Attilio Piccioni, were implicated in Montesi’s death though both were formally absolved. In addition to ‘il caso Montesi’, Hodges’ script for Pulp was inspired by stories of the actor George Raft, whose career decline followed his conviction for tax evasion in 1965 and precipitated rumours that he was involved with the Mafia (consolidated by his 1966 testimony in front of a grand jury focusing on the financial dealings of the Mafia), leading in 1967 to Raft being prohibited from entering the UK, where he was director of the Colony Club casino. Raft became the inspiration for the character of Preston Gilbert (Hodges, op cit.). Further to this, Pulp’s narrative drew on the story of Wilma Montesi, a 21 year old woman whose dead body was found on a beach near Torvajanica in 1953, contradictory information given about the case and about the circumstances of her death leading to a widespread suggestion that some sort of conspiracy was at play and the authorities were attempting a ‘cover-up’. Notorious playboy Ugo Montagna and Piero Piccioni, the son of vice prime minister Attilio Piccioni, were implicated in Montesi’s death though both were formally absolved. In addition to ‘il caso Montesi’, Hodges’ script for Pulp was inspired by stories of the actor George Raft, whose career decline followed his conviction for tax evasion in 1965 and precipitated rumours that he was involved with the Mafia (consolidated by his 1966 testimony in front of a grand jury focusing on the financial dealings of the Mafia), leading in 1967 to Raft being prohibited from entering the UK, where he was director of the Colony Club casino. Raft became the inspiration for the character of Preston Gilbert (Hodges, op cit.).

Within this web of influences, Hodges created Mickey King, the Mickey Spillane-like author of lurid hardboiled crime novels, many of them written under suggestive pseudonyms (Guy Strange, Les Behan, Paul R Cumming, O R Gan), and with equally suggestive titles (‘My Gun is Long’, ‘The Organ Grinder’). King becomes ‘trapped as securely as a fly on fly paper by a plot every bit as lurid as his own novels’ (Hodges, op cit.). Hodges also included a gag revolving around Caine’s inability to drive, something which had shocked Hodges on the set of Get Carter when, during the shooting of a specific scene Hodges asked one of his assistants to tell Caine to get in a car and drive it. The assistant informed a surprised Hodges that Caine could not drive and the scenes in Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1965) in which Caine’s character was driving were achieved by Caine sitting in cars that were being towed.  Though the film is for much of its running time ironic and playful, its thematic content is deeply serious, and this becomes increasingly apparent as the film nears its denouement: the picture deals with corruption and manipulation, subtly exploring the seductive appeal of fascism, violence and criminality. Gilbert’s criminal behaviour is, the film reveals, intertwined with the history of Prince Cippola, the fascist politico to whom Gilbert’s ex-wife Betty is now married. The pair are implicated in the deaths of the young girl on the beach, a victim of the hedonistic orgies arranged by Cippola, Gilbert and other nameless influential figures. However, the film suggests, these figures will not be brought to justice: the FBI agent, listed in the credits as The Bogeyman (and played by Humphrey Bogart-alike Robert Sacchi), investigating Miller’s death tells Mickey to forget what he has discovered. ‘You go around talking that kind of crap and you’ll rock the boat. A lot of important people are involved’. The film ends with Mickey in the care of Dinuccio and Betty Cippola, shots of Mickey interspersed with fragments of an ostentatious hunt presided over by Prince Cippola. Though the film is for much of its running time ironic and playful, its thematic content is deeply serious, and this becomes increasingly apparent as the film nears its denouement: the picture deals with corruption and manipulation, subtly exploring the seductive appeal of fascism, violence and criminality. Gilbert’s criminal behaviour is, the film reveals, intertwined with the history of Prince Cippola, the fascist politico to whom Gilbert’s ex-wife Betty is now married. The pair are implicated in the deaths of the young girl on the beach, a victim of the hedonistic orgies arranged by Cippola, Gilbert and other nameless influential figures. However, the film suggests, these figures will not be brought to justice: the FBI agent, listed in the credits as The Bogeyman (and played by Humphrey Bogart-alike Robert Sacchi), investigating Miller’s death tells Mickey to forget what he has discovered. ‘You go around talking that kind of crap and you’ll rock the boat. A lot of important people are involved’. The film ends with Mickey in the care of Dinuccio and Betty Cippola, shots of Mickey interspersed with fragments of an ostentatious hunt presided over by Prince Cippola.

The various characters’ responses to Mickey’s novels reflect Hodges’ own feelings regarding witnessing cinema audiences react to Get Carter, his first feature film, and Hodges’ realisation of the power fiction holds over its audiences: ‘I could hear every reaction, feel the excitement. They were hooked. They gasped and laughed on cue. It was heady stuff all right, but I found it unnerving. I hadn’t anticipated the sense of power you can get as a director. It was Pavlovian and I found that scary’ (Hodges, quoted in Davies, 2002). Where Hodges expected people to be ‘shocked’ or ‘disgusted’ at the violence of the story, he discovered ‘they weren’t. Many of them had a good time with it. They were exhilirated’ (Hodges, quoted in ibid.). Hodges thought that he would like to ‘make a film about why people want to go and see violence, and about the commercialization of violence. I wanted to make it funny too’ (Hodges, quoted in Spicer & McKenna, 2013: 81). Hodges was also surprised at people’s reactions to him, saying that after the release of Get Carter, people looked at him differently: ‘They couldn’t believe the small, gentle man they knew could make such a film [….] Even to this day the farmer who lives up the road from me asks me how I could have possibly made such a vile picture’ (Hodges, quoted in Davies, op cit.).  The film confronts this issue via its depiction of various characters’ responses to Mickey’s lurid writing. In the opening sequence, Mickey is heard on the soundtrack dictating his new novel (‘The Organ Grinder’) via an audio recording, whilst onscreen we see the reactions of the women in the typing pool (‘somewhere in the Mediterranean’, an onscreen title tells us) to the material they are being asked to transcribe. The audio track flits seamlessly between several scenarios that Mickey has dictated, including a sex scene and a scene of fetishistic violence which climaxes with the protagonist of Mickey’s novel whipping his enemy. Onscreen, we see the typists, in a pool whose usual work is typing up legal documents and shipping manifests, reacting to Mickey’s work: a frumpy middle-aged woman, the head of the typing pool, putting on a professional face though her expression betrays her subtle disapproval at what she is listening to; another frumpy woman, much younger and wearing spectacles, who looks horrified at the scene that she is transcribing but gets the giggles when she looks at another of her colleagues, who clearly finds the sex scene she is transcribing to be highly amusing. When Mickey arrives at the building to collect his typed manuscript, he is called into the owner’s office; Mickey expects to be chastised when the owner claims that his employees found the document ‘too stimulating’ and reacts sharply, but soon realises that the male owner of the business is flirting with him, clearly believing from the none-too-subtle homoerotic content of the document that Mickey is gay. The film confronts this issue via its depiction of various characters’ responses to Mickey’s lurid writing. In the opening sequence, Mickey is heard on the soundtrack dictating his new novel (‘The Organ Grinder’) via an audio recording, whilst onscreen we see the reactions of the women in the typing pool (‘somewhere in the Mediterranean’, an onscreen title tells us) to the material they are being asked to transcribe. The audio track flits seamlessly between several scenarios that Mickey has dictated, including a sex scene and a scene of fetishistic violence which climaxes with the protagonist of Mickey’s novel whipping his enemy. Onscreen, we see the typists, in a pool whose usual work is typing up legal documents and shipping manifests, reacting to Mickey’s work: a frumpy middle-aged woman, the head of the typing pool, putting on a professional face though her expression betrays her subtle disapproval at what she is listening to; another frumpy woman, much younger and wearing spectacles, who looks horrified at the scene that she is transcribing but gets the giggles when she looks at another of her colleagues, who clearly finds the sex scene she is transcribing to be highly amusing. When Mickey arrives at the building to collect his typed manuscript, he is called into the owner’s office; Mickey expects to be chastised when the owner claims that his employees found the document ‘too stimulating’ and reacts sharply, but soon realises that the male owner of the business is flirting with him, clearly believing from the none-too-subtle homoerotic content of the document that Mickey is gay.

This theme resurfaces in Mickey’s encounter with Jake. The pair meet on the coach on which Dinuccio has placed Mickey. Jake is reading one of Mickey’s novels, ‘My Gun is Long’, written under the pen-name ‘Guy Strange’. Mickey takes this as a sign that Jake is the contact Dinuccio has told Mickey about, and that Dinuccio will lead Mickey to his mysterious client. (The film swiftly reveals that this is a misunderstanding, though later sequences show us that Jake and Gilbert are connected in a very different way.) ‘Contact was made through one of my books’, Mickey narrates, ‘A nice touch that, and good for my royalties’. ‘What do you write?’, Jake asks Mickey when Mickey reveals that he is a writer – without letting on that he is ‘Guy Strange’. ‘Gangster fiction’, Mickey replies, ‘“Pulp” would be less pompous and more accurate’. They become involved in a discussion of Mickey’s fiction, Mickey needling Jake into an objective appraisal of ‘My Gun is Long’ but being none too happy when Jake obliges: ‘Your plot line is too thin’, Jake tells him, ‘Relies too much on coincidence [….] Puts your story beyond the bounds of believability’. Of course, the same is true of Hodges’ film itself, and this is one of the most overtly self-referential lines of dialogue in the picture; later in the narrative, Mickey reflects on the convoluted plot into which he has been thrown, stating that ‘This story was like a pornographic photograph: difficult to know who was doing what and to whom’. Mickey is unimpressed with Jake, in his narration observing that ‘They’d given the job to a screwball. All that reading had gone to his stomach. He was constipated with pulp, and now it was coming out, all over me’.  At the Hotel Albert, following the mix-up over Jake and Mickey’s rooms, Mickey finds Jake dead in Mickey’s bathtub and concludes that Jake was killed by an assassin who was really targeting Mickey. Mickey riffles through Jake’s belongings, discovering that the pulp-loving Jake is actually a senior lecturer in English at Berkeley University – a revelation that smashes the stereotype with which Mickey had associated Jake, and also suggests Jake’s assessment of Mickey’s novel came from a position of authority. Mickey wonders ‘who he was, the poor dead bastard. Why had he panicked on the bus, when I put the finger on him?’ Mickey also discovers in Jake’s luggage a woman’s outfit, concluding that ‘The guy was a fag, a transvestite. That explains his panic, but not his death. An ugly thought made my waters curdle: that should have been me in there having a bath. Miller was my stand-in with death’; again, as with the scene in which the owner of the typing pool office comes on to Mickey, the suggestion of an alternative to the hardboiled, macho version of masculinity punctures Mickey’s worldview, destabilising it. At the Hotel Albert, following the mix-up over Jake and Mickey’s rooms, Mickey finds Jake dead in Mickey’s bathtub and concludes that Jake was killed by an assassin who was really targeting Mickey. Mickey riffles through Jake’s belongings, discovering that the pulp-loving Jake is actually a senior lecturer in English at Berkeley University – a revelation that smashes the stereotype with which Mickey had associated Jake, and also suggests Jake’s assessment of Mickey’s novel came from a position of authority. Mickey wonders ‘who he was, the poor dead bastard. Why had he panicked on the bus, when I put the finger on him?’ Mickey also discovers in Jake’s luggage a woman’s outfit, concluding that ‘The guy was a fag, a transvestite. That explains his panic, but not his death. An ugly thought made my waters curdle: that should have been me in there having a bath. Miller was my stand-in with death’; again, as with the scene in which the owner of the typing pool office comes on to Mickey, the suggestion of an alternative to the hardboiled, macho version of masculinity punctures Mickey’s worldview, destabilising it.

Mickey is a cynical and somewhat shiftless protagonist, the film establishing an ironic distance from him. ‘The day started quietly enough’, Mickey notes in his opening voiceover, ‘Then I got out of bed. That was my first mistake [….] That’s how it all began. That bizarre adventure that put five people in the cemetery and ruled me out as a customer for laxatives’. His abandonment of his family in favour of writing trashy novels is presented casually: ‘Handling stiffs was hardly the life for someone with a burning creative urge’, he narrates, ‘So I elbowed the loved ones’. However, Mickey doesn’t seem to like the act of writing too much, pushing the task on to the employees of the typing pool and observing that ‘The writer’s life would be ideal but for the writing. That was a problem I’d have to overcome’. By contrast, Rooney invests Preston Gilbert with a restless energy, the character exhibiting a tendency towards unpleasant and unwarranted practical jokes and displaying an excess of vanity. Gilbert is introduced in the act of dressing for the day, Gilbert peeling back layers of mirrors and admiring himself in each of them. Gilbert has, Mickey suggests, become absorbed by his roles in gangster films: ‘Didn’t his roles on and offscreen get slightly confused?’, Mickey asks Liz. ‘That happens to all actors’, she responds. However, Gilbert’s luxurious island home is also a prison of sorts, described in Mickey’s narration as ‘A kind of rich man’s Alcatraz’.  Hodges found directing Rooney difficult, as Rooney was apt to improvise physical bits of business during his scenes which made matching shots almost impossible, and Hodges learnt that he had to ‘shoot even the rehearsals because he’d [Rooney] never do the same thing twice. The freshness would soon evaporate and he’d become mechanical’ (Hodges, quoted in Davies, op cit.). Hodges also faced some issues during postproduction, the film’s original editor treating the material ‘too reverently’: ‘He was making an “art” film – which I certainly wasn’t’ (Hodges, quoted in ibid.). Hodges eventually fired the editor, hiring John Glen instead, Glen reassembling the whole picture from scratch. Hodges found directing Rooney difficult, as Rooney was apt to improvise physical bits of business during his scenes which made matching shots almost impossible, and Hodges learnt that he had to ‘shoot even the rehearsals because he’d [Rooney] never do the same thing twice. The freshness would soon evaporate and he’d become mechanical’ (Hodges, quoted in Davies, op cit.). Hodges also faced some issues during postproduction, the film’s original editor treating the material ‘too reverently’: ‘He was making an “art” film – which I certainly wasn’t’ (Hodges, quoted in ibid.). Hodges eventually fired the editor, hiring John Glen instead, Glen reassembling the whole picture from scratch.

Video

Arrow’s presentation of Pulp is based on a new 2k restoration of the film from ‘original film elements’ that was ‘supervised and approved’ by Ousama Rawi, the film’s director of photography. Arrow’s presentation of Pulp is based on a new 2k restoration of the film from ‘original film elements’ that was ‘supervised and approved’ by Ousama Rawi, the film’s director of photography.

The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 27Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 (though interestingly, the framing on all four sides is slightly tighter than the 1.78:1 framing of the film’s DVD releases from MGM) and is uncut, with a running time of 95:43 mins. The presentation begins with the original BBFC ‘AA’ certificate and United Artists logo (though these are accompanied on the soundtrack by the musical ‘sting’ of the late-1980s MGM/UA logo). Ousama Rawi’s 35mm colour photography for the picture is filled with rigid, formal compositions dominated by symmetry or in which formal symmetry is disturbed by movement. The photography favours shorter focal lengths, resulting in strong depth of field. The painterly compositions are complemented by Rawi’s shooting around the harsh Mediterranean sun, which results in a contrast between strong light and deep shadows. It’s a beautifully photographed film. Arrow’s presentation is equally pleasing, and is free from any distracting damage. A very good level of fine detail is present throughout the film, and contrast levels are equally strong and nicely balanced, the range of midtones being expressed with the nuance of 35mm film and the deep shadows tapering off into rich blacks. Highlights are balanced too. The boldness of the contrast and texture of the picture suggest the ‘original film elements’ used for the restoration were positive elements (perhaps an interpositive or even a print) and not the original negative. Colour is communicated well too, though differently to the film’s DVD releases: in comparison with the film’s previous DVD releases, the palette of Arrow’s presentation has a stronger amber hue, resulting in more natural skin tones. This is presumably commensurate with Rawi’s original intentions, given the director of photography’s involvement in this presentation. Finally, a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 track. This is rich and has good range, offering a satisfyingly bassy experience in places. The accompanying English subtitles (optional) are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes the following: The disc includes the following:

- Interview with Mike Hodges (17:36). In a new interview, director Mike Hodges reflects on the genesis of Pulp and talks about his inspirations in writing the picture. He discusses ‘Rumour’, the TV movie he made for ITV in 1970, and the significance of the ironic narration in that picture, and how this was carried over to the script for Pulp. He also talks about the political context and his awareness of the re-emergence of the Fascist Party in Italy during the late 1960s, and how this fed into Pulp too. - Interview with Ousama Rawi (9:15). Rawi, the film’s director of photography, is interviewed about his work on the picture. Rawi talks about the significance of Pulp in his transition from making commercials to shooting feature films. He discusses the techniques he used in lighting the picture. - Interview with John Glen (4:59). Pulp’s editor, John Glen, discusses his working relationship with Michael Klinger and how he came to edit Pulp. - Interview with Tony Klinger (6:07). Ton Klinger, the son of Michael Klinger, talks about his father’s work and discusses the genesis and production of Pulp. - Trailer (2:04). - Galleries: Gallery 1 (52 images); Gallery 2 (52 images); Gallery 3 (52 images); Gallery 4 (51 images).

Overall

Pulp is an excellent film, a blackly comic picture that has the texture and depth of Hodges’ best work. Thanks to Hodges’ previous work as a documentarian, Hodges pictures – from Get Carter to Croupier (1998) – have been characterised by a strong understanding of place and engagement with society. Pulp is no exception to this, making excellent use of its Mediterranean locations and offering a blackly comic plot that gradually reveals the horror of Hodges’ realisation that even so soon after the Holocaust, fascism had a seductive appeal and was seeing a re-emergence in Italy, in particular. Hodges’ best films are notable for their refusal to talk down to their audience or to pander to convention, something which has led Hodges into conflict with his producers (notably on A Prayer for the Dying, 1987). Again, Pulp is no exception, leading its audience into a conclusion which may be equally satisfying or frustrating, depending on the viewer’s point of view – but certainly, the film refuses to offer easy solutions to the questions it asks. In the days of Operation Yewtree and the current fascination with the sexual kinks of public figures and alleged ‘cover ups’, the film’s plot seems just as relevant as it did in the 1970s. Pulp is an excellent film, a blackly comic picture that has the texture and depth of Hodges’ best work. Thanks to Hodges’ previous work as a documentarian, Hodges pictures – from Get Carter to Croupier (1998) – have been characterised by a strong understanding of place and engagement with society. Pulp is no exception to this, making excellent use of its Mediterranean locations and offering a blackly comic plot that gradually reveals the horror of Hodges’ realisation that even so soon after the Holocaust, fascism had a seductive appeal and was seeing a re-emergence in Italy, in particular. Hodges’ best films are notable for their refusal to talk down to their audience or to pander to convention, something which has led Hodges into conflict with his producers (notably on A Prayer for the Dying, 1987). Again, Pulp is no exception, leading its audience into a conclusion which may be equally satisfying or frustrating, depending on the viewer’s point of view – but certainly, the film refuses to offer easy solutions to the questions it asks. In the days of Operation Yewtree and the current fascination with the sexual kinks of public figures and alleged ‘cover ups’, the film’s plot seems just as relevant as it did in the 1970s.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation is very satisfying indeed, the main presentation having input from the film’s director of photography, Ousama Rawi, and being supported with some excellent contextual material in the form of interviews with principal members of the crew. This is an excellent release of a long-neglected film which deserves to be drawn out from the shadow of Hodges’ more famous debut feature, Get Carter. References: Davies, Steven Paul, 2002: ‘Get Carter’ and Beyond: The Cinema of Mike Hodges. London: Batsford Ltd Hodges, Mike, 2017: ‘The letter that J.G. Ballard wrote to me about my thriller Pulp’. [Online.] http://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/malta-mafia-michael-caine-making-pulp Spicer, Andrew & McKenna, A T, 2013: The Man Who Got Carter: Michael Klinger, Independent Production and the British Film Industry, 1960-1980. London: I B Tauris Full-size screengrabs (click to enlarge):

|

|||||

|