|

|

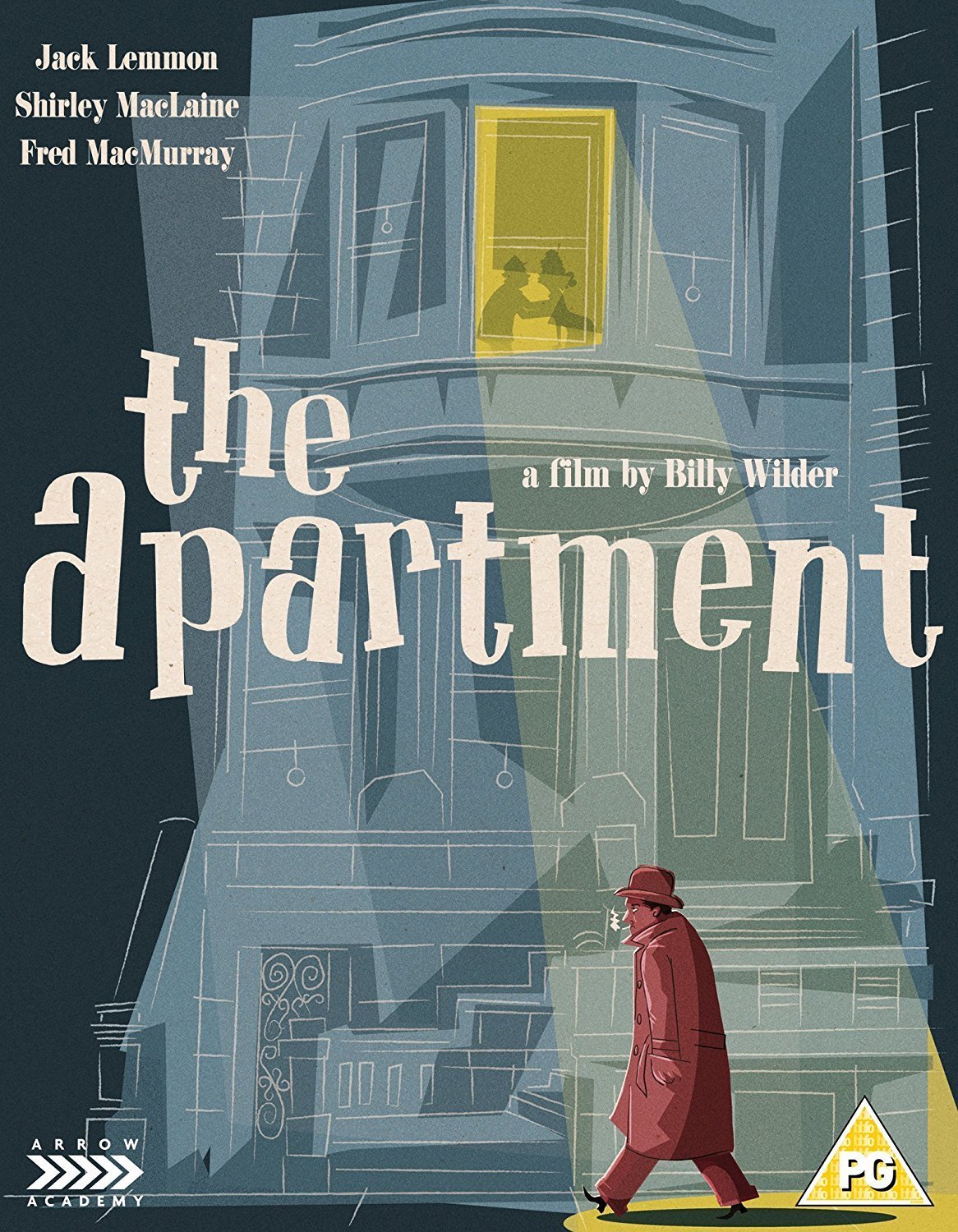

Apartment (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th January 2018). |

|

The Film

The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960) The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960)

C C ‘Bud’ Baxter (Jack Lemmon) lives an unrewarding life as a clerk for an insurance company. He rents an apartment in which he lives alone, and in order to curry favour with his superiors and get ahead on the career ladder, Bud has taken to ‘lending’ his apartment to his married colleagues so that they may liaise with their mistresses. The walls are paper-thin, and Bud’s neighbours believe Bud to be a Don Juan. Bud is interested in Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), one of the elevator girls who works in the high rise building. When Bud is called to the office of senior executive Jeff Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray), he agrees to let Sheldrake use his apartment in exchange for a promised promotion. However, Bud is unaware that Sheldrake intends to use the apartment to meet Fran. Sheldrake was involved in an affair with Fran but broke it off, leaving Fran devastated. Now Sheldrake wants to rekindle that affair and takes Fran to Bud’s apartment. Bud receives his promotion to administrative assistant. At the office Christmas party, Sheldrake’s secretary Miss Olsen (Edie Adams), one of Sheldrake’s previous mistresses, warns Fran against rekindling her affair with Sheldrake. She tells Fran that she is simply one in a long line of Sheldrake’s ‘conquests’. That night, Fran meets Sheldrake at Bud’s apartment. Sheldrake tells Fran that he cannot leave his wife, and when Sheldrake leaves, Fran takes an overdose of sleeping pills. Bud returns to his apartment and finds the unconscious Fran. He seeks the assistance of his neighbour Dr Dreyfuss (Jack Kruschen) and his wife Mildred (Naomi Stevens). They nurse Fran back to health. Bud contacts Sheldrake but Sheldrake refuses to assist Fran, telling Bud that he must do it by himself. Over Christmas, Bud takes care of Fran, though her absence from the family home is noted by her sister and brother-in-law Karl Matuschka (Johnny Seven). A taxi driver and heavy, Matuschka discovers Fran has been staying in Bud’s apartment, and jumping to all the wrong conclusions, Matuschka assaults Bud. As Bud makes plans to tell Sheldrake that he is in love with Fran, Bud is forced to make a choice between his career and his newfound love for a woman.  The third picture in the long-term collaboration between Billy Wilder and writer I A L Diamond (following 1957’s Love in the Afternoon and 1959’s Some Like It Hot), The Apartment was inspired by Wilder’s viewing of David Lean’s Brief Encounter in 1945. Upon viewing Lean’s picture, Wilder had written in his black notebook, in which he recorded his ideas for films, some notes questioning the role of Alec’s friend Stephen, who lends Alec his apartment so that the married Alec may arrange a liaison with his lover Laura: ‘What about the friend who owned the flat?’, wondered Wilder, ‘Here is a lonely bachelor who comes home to his apartment and crawls into a bed that is still warm from the lovers who had been there earlier’ (Wilder, quoted in Phillips, 2010: 231). Wilder discussed the scenario with Diamond, and the pair drew a connection between this idea and a scandal that had taken place in 1951, when Walter Wanger’s wife Joan Bennett was involved in an affair with an agent named Jennings Lang (who later became a producer and screenwriter): Lang had borrowed a subordinate’s apartment and used it as a ‘love nest’ (see ibid.). Wanger caught Bennett and Lang, shooting Lang in the left thigh and groin. The third picture in the long-term collaboration between Billy Wilder and writer I A L Diamond (following 1957’s Love in the Afternoon and 1959’s Some Like It Hot), The Apartment was inspired by Wilder’s viewing of David Lean’s Brief Encounter in 1945. Upon viewing Lean’s picture, Wilder had written in his black notebook, in which he recorded his ideas for films, some notes questioning the role of Alec’s friend Stephen, who lends Alec his apartment so that the married Alec may arrange a liaison with his lover Laura: ‘What about the friend who owned the flat?’, wondered Wilder, ‘Here is a lonely bachelor who comes home to his apartment and crawls into a bed that is still warm from the lovers who had been there earlier’ (Wilder, quoted in Phillips, 2010: 231). Wilder discussed the scenario with Diamond, and the pair drew a connection between this idea and a scandal that had taken place in 1951, when Walter Wanger’s wife Joan Bennett was involved in an affair with an agent named Jennings Lang (who later became a producer and screenwriter): Lang had borrowed a subordinate’s apartment and used it as a ‘love nest’ (see ibid.). Wanger caught Bennett and Lang, shooting Lang in the left thigh and groin.

The Apartment depicts corporate life as stultifying and claustrophobic: the floorspace in Baxter’s bullpen office may be huge, but it is filled with people and objects, all arranged in a symmetrical, uniform manner – something which is emphasised by the use of short focal lengths in the film’s photography, which gives extraordinary depth of field and makes the line of desks and employees seem never-ending. J Levinson has argued that The Apartment ‘is the most pointed and caustic [Hollywood film] in its take on the prevailing workings of big business’, describing the picture as ‘a poison pen letter to corporate America’ that is ‘teeming with disgruntled white-collar workers, conformist organization men, and achingly lonely crowds’ (Levinson, 2012: np). As the film opens, Baxter’s narration identifies the location of his desk (Premium Accounting Division, Section W, Desk Number 861) and his pay: these are the elements that define Baxter, and presumably many of his colleagues, underscoring the inhumanity of the corporate mindset and reinforcing the sense of scale of the corporation. Within the corporation, people are reduced to numbers, job roles/titles and their economic ‘value’. The corporation is also very clearly not a meritocracy. The only hope of ‘progression’ or movement out of the sense of stasis engendered by long-term job roles, it seems, is to devise a scheme that allows oneself to curry favour with more influential people within the corporation. Baxter’s scheme involves lending his apartment to senior colleagues, so that they may liaise with (and presumably engage in intercourse with) their mistresses. Even after Fran has attempted suicide, the pressure of corporate advancement and conformity is so great that Baxter continues to acquiesce to Sheldrake’s demands that Baxter ‘cover up’ Sheldrake’s relationship with Fran and later enable Sheldrake to continue using the apartment.  It’s a sleazy premise, and Baxter’s arrangement with his senior colleagues is depicted as a Faustian pact that takes its toll on Baxter’s soul. When Fran overdoses and Baxter seeks the help of his neighbour, a doctor, to nurse her back to consciousness and full health, believing that Baxter has been conducting affairs with a string of women at his apartment, Baxter’s neighbour asks Baxter, ‘Why don’t you grow up, Baxter? Be a mensch’. At the end of the picture, when Baxter finally sees the proverbial light, turning against Sheldrake and refusing to loan him his apartment before resigning from his job, Baxter echoes the doctor’s words: ‘I’ve decided to become a mensch’, Baxter tells Sheldrake, ‘You know what that is? A human being!’ It’s a sleazy premise, and Baxter’s arrangement with his senior colleagues is depicted as a Faustian pact that takes its toll on Baxter’s soul. When Fran overdoses and Baxter seeks the help of his neighbour, a doctor, to nurse her back to consciousness and full health, believing that Baxter has been conducting affairs with a string of women at his apartment, Baxter’s neighbour asks Baxter, ‘Why don’t you grow up, Baxter? Be a mensch’. At the end of the picture, when Baxter finally sees the proverbial light, turning against Sheldrake and refusing to loan him his apartment before resigning from his job, Baxter echoes the doctor’s words: ‘I’ve decided to become a mensch’, Baxter tells Sheldrake, ‘You know what that is? A human being!’

The women in the corporation are little more than sexual prey for men like Sheldrake. One of Bud’s colleagues complains about Fran, asserting that ‘a lot of guys around here have tried lots of different approaches [to get her in bed]. What’s she trying to prove?’ ‘Could be that she’s just a nice, respectable girl’, Bud responds. ‘Listen to him’, the colleague asserts sarcastically, ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy!’ Fran, who suffers seemingly constant sexual harassment in her job as an elevator girl, is simply one in a long line of mistresses that Sheldrake has taken. (It seems intentional that Fran’s job confines her to an elevator, this sense of physical ‘imprisonment’ acting as a metaphor for the manner in which Fran becomes trapped in her affair with Sheldrake.) These former mistresses include Sheldrake’s current secretary Miss Olsen, who becomes incensed at Sheldrake’s shameless treatment of Fran, to the extent that Olsen’s frank conversation with Fran precipitates Fran’s suicide attempt, and when Fran is recovering Olsen arranges to meet Sheldrake’s wife and tell her the truth about her philandering husband. The film’s examination of sexuality is surprisingly frank, and the picture’s fairly open (though still slightly circumlocutory) focus on infidelity and sexual promiscuity is an index of the changes that would begin to take place during the 1960s – not only in cinema’s depiction of sexuality, but in the discourse surrounding sexuality more generally. Alison R Hoffman has compared The Apartment with Hitchcock’s Psycho, released in the same year: both films, Hoffman suggests, ‘punish’ a ‘working-class “single girl”’ for her flirtations with sexuality and desire, and both pictures were made on the cusp ‘of the neo-Victorianism of the 1950s and the coming sexual revolution of the late 1960s’ (Hoffman, 2011: 71). ‘From what I hear through the walls, you got something going every night’, Bud’s neighbour Dr Dreyfuss notes near to the start of the film, adding that some nights it’s a ‘double header’ and suggesting that Bud should leave his body to science – so that they may study how a single man may be so sexually promiscuous. This sequence ends in delicious irony, with Bud being depicted eating his dinner in front of the television, his planned viewing of a broadcast of Edmund Goulding’s 1932 film Grand Hotel aborted by the sheer number of commercials. Ultimately, the film juxtaposes the stultifying isolation and monotony of corporate life with the sense of community and belonging of the apartment building in which Bud lives (and from which, for much of the film’s running time, he separates himself – until, that is, he decides to become a ‘mensch’). ‘You know, I used to live like Robinson Crusoe’, Bud tells Fran near the end of the film, ‘Shipwrecked among eight million people. Then one day I saw a footprint in the sand, and there you were’. The Apartment is a sharp critique of corporatism and the lack of connection and communication in the modern world that has lost none of its bite in the years since its release; in fact, its thematic content seems perhaps more relevant today than it was in 1960, and the film has been a clear influence on later depictions of social and sexual politics in a corporate setting, such as Neil Labute’s play (and 1996 film adaptation) In the Company of Men.

Video

Photographed in Cinemascope, The Apartment is here presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film’s photography makes strong use of shorter focal lengths, creating a strong depth of field in most of its scenes; this enables the sense of uniformity and regimentation in the office scenes to be communicated via the endless rectilinear lines of desks and employees, and in the scenes set in Bud’s apartment it also allows a character (Bud or Fran) to be shown in close-up or mid-shot in the foreground whilst the other is engaged in bits of business in the background and in the opposite half of the frame. This sense of staging in depth is communicated excellently in this Blu-ray presentation, which is based on a new 4k restoration of the film from the original negative. The 35mm monochrome image is carried in this presentation by good, evenly-balanced contrast levels, resulting in strongly defined mid-tones, balanced highlights and shadows that taper off into rich blacks. Detail is excellent throughout, a very pleasing level of fine detail present in the image, and a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The film’s previous Blu-ray release from MGM wasn’t terrible but was marred by some noticeable damage and inconsistent black levels, but Arrow’s new presentation improves noticeably on that previous release and offers the best home video presentation this picture has had. Photographed in Cinemascope, The Apartment is here presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. The film’s photography makes strong use of shorter focal lengths, creating a strong depth of field in most of its scenes; this enables the sense of uniformity and regimentation in the office scenes to be communicated via the endless rectilinear lines of desks and employees, and in the scenes set in Bud’s apartment it also allows a character (Bud or Fran) to be shown in close-up or mid-shot in the foreground whilst the other is engaged in bits of business in the background and in the opposite half of the frame. This sense of staging in depth is communicated excellently in this Blu-ray presentation, which is based on a new 4k restoration of the film from the original negative. The 35mm monochrome image is carried in this presentation by good, evenly-balanced contrast levels, resulting in strongly defined mid-tones, balanced highlights and shadows that taper off into rich blacks. Detail is excellent throughout, a very pleasing level of fine detail present in the image, and a strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. The film’s previous Blu-ray release from MGM wasn’t terrible but was marred by some noticeable damage and inconsistent black levels, but Arrow’s new presentation improves noticeably on that previous release and offers the best home video presentation this picture has had.

Audio

The disc offers two audio options: (i) a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track; and (ii) a LPCM 1.0 track. Both tracks display a strong sense of range and depth. The surround track is a little more shrill, crisper and sharper than the LPCM mono track and features some artificial-sounding sound separation. Purists will want to stick with the mono track. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are accurate and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with film historian Bruce Block. This is the same audio commentary that has appeared on some of the film’s previous DVD and Blu-ray releases. It’s a carefully-research commentary track that explores the film’s production and its lasting legacy. - ‘The Key to The Apartment’ (10:12). Film critic Philip Kemp offers an appreciation of the film. This is complemented by: - Selected Scene Commentary from Philip Kemp (8:37). Kemp provides commentary on the scene in which Bud meets floozy Margie MacDougall (played by Hope Holiday) in a bar on Christmas Eve, and the scene in which Fran and Sheldrake meet for the first time. Kemp examines the two scenes, exploring the manner in which Wilder juxtaposes comedy with tragedy and seamlessly interweaves the two. - ‘The Flawed Couple’ (20:24). This interesting new video essay, narrated by David Cairns, focuses on the films on which Wilder and Lemmon collaborated before examining some of Wilder’s later pictures. - ‘A Letter to Castro’ (13:24). Hope Holiday is interviewed about her role in the film. - ‘An Informal Conversation with Billy Wilder’ (23:17). This archival audio interview with Wilder was sourced from recordings made by the Writers Guild of America. Wilder talks about his techniques and methods, using his recollections of the making of The Apartment essentially as a case study. - Restoration Showreel (2:20). This brief featurette demonstrates a ‘before’ and ‘after’ the restoration process. - Trailer (2:19). - ‘Inside The Apartment’ (29:36). This featurette was produced in 2007 for one of the film’s DVD releases and features input from MacLaine; Paul Diamond, the son of I A L Diamond; film historians Drew Casper, Ed Sikov and Robert Osborne; Kevin Lally, the author of Wilder Times; film theorist Molly Haskell; Jack Lemmon’s son Chris Lemmon; Joe Baltake, author of a biography of Lemmon; actors Edie Adams and Johnny Seven; and executive producer Walter Mirisch. - ‘Magic Time: The Art of Jack Lemmon’ (12:47). This featurette was also produced in 2007 and focuses on Jack Lemmon’s acting. It sees input from Chris Lemmon, Joe Baltake, Robert Osborne, Molly Haskell and Kevin Lally.

Overall

The Apartment is a wonderfully sharp and witty film, though it has its detractors and some see it as the beginning of Wilder’s decline. (Personally, I can’t agree with that sentiment, and in my view The Apartment and some of Wilder’s later films are the equal of his earlier classics.) The film contains some delicious ironies and some savage injokes: in particular, Wilder fires a subtle broadside at Marilyn Monroe, whose alleged diva-esque demands on the set of Some Like It Hot alienated the director. Calling Bud in the middle of the night, his colleague Joe Dobisch demands that Bud let him use the apartment asap: ‘I can’t pass this up. She looks like Marilyn Monroe’, Dobisch asserts as a dreamy, doey-eyed Monroe-alike sidles up next to him. The Apartment is a wonderfully sharp and witty film, though it has its detractors and some see it as the beginning of Wilder’s decline. (Personally, I can’t agree with that sentiment, and in my view The Apartment and some of Wilder’s later films are the equal of his earlier classics.) The film contains some delicious ironies and some savage injokes: in particular, Wilder fires a subtle broadside at Marilyn Monroe, whose alleged diva-esque demands on the set of Some Like It Hot alienated the director. Calling Bud in the middle of the night, his colleague Joe Dobisch demands that Bud let him use the apartment asap: ‘I can’t pass this up. She looks like Marilyn Monroe’, Dobisch asserts as a dreamy, doey-eyed Monroe-alike sidles up next to him.

The Apartment offers a cynical depiction of corporatism, and in this sense – and in its depiction of sexual politics – the film arguably seems as relevant today as in 1960. Certainly, it’s become a reference point for many more recent films about corporate life and the corporate mentality. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation easily improves over the film’s previous HD release, and offers a very pleasing presentation of The Apartment. This strong presentation of the main feature is accompanied by some excellent new contextual material, alongside the archival material produced for the film’s previous DVD/BD releases. This is a superb release of Wilder’s film, and should prove to be an essential purchase for fans of the director. References: Levinson, Julie, 2012: The American Success Myth on Film. London: Palgrave-Macmillan Hoffman, Alison R, 2011: ‘Shame and the Single Girl: Reviving Fran and Falling for Baxter in The Apartment’. In: McNally, Karen (ed), 2011: Billy Wilder, Movie-Maker: Critical Essays on the Films. London: McFarland & Company: 71-86 Phillips, Gene, 2010: Some Like it Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. The University Press of Kentucky

|

|||||

|