|

|

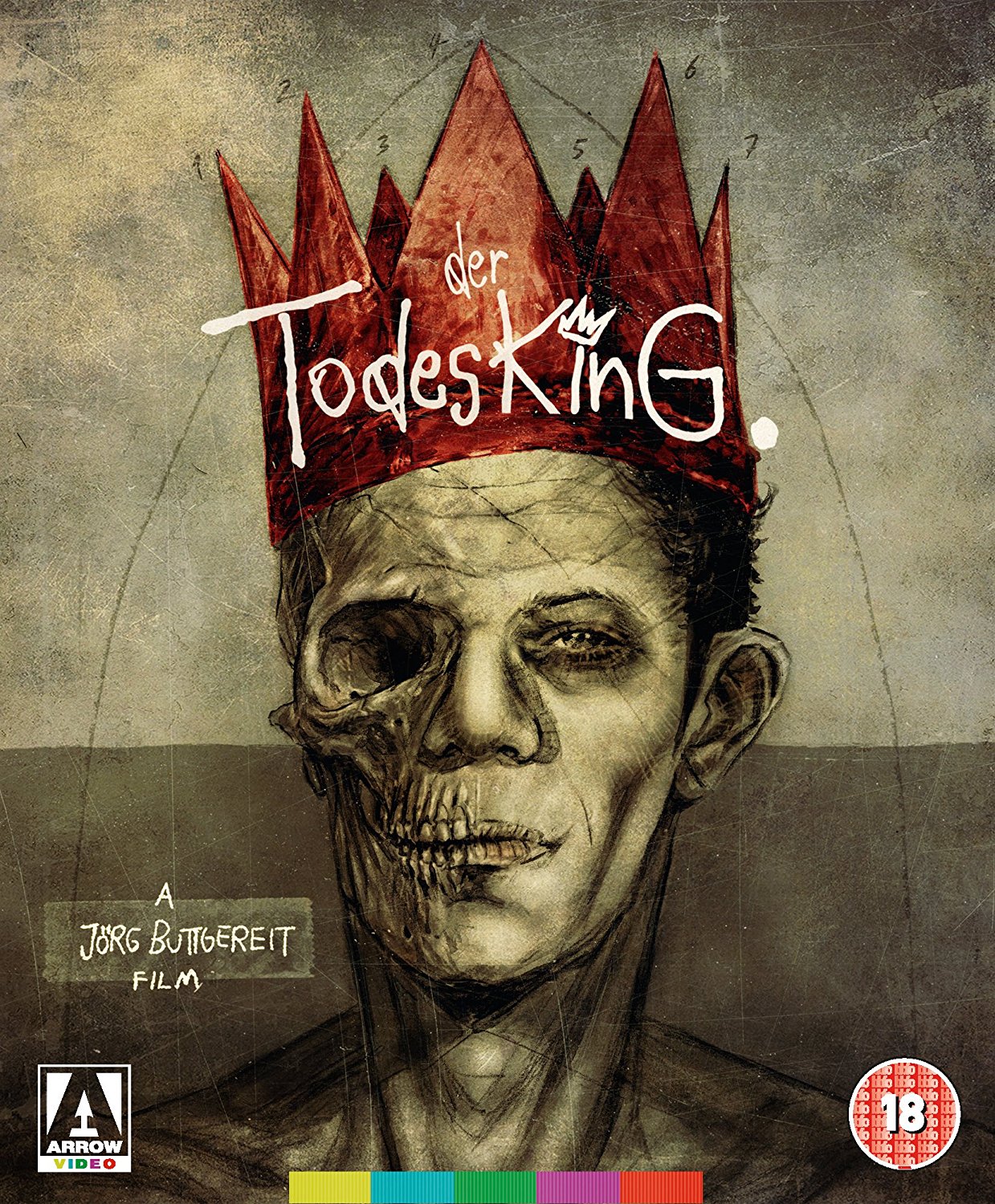

Death King (The) AKA Der Todesking (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd March 2018). |

|

The Film

Der Todesking (Jorg Buttgereit, 1990) Der Todesking (Jorg Buttgereit, 1990)

Against a black screen, a naked man collapses and dies. Throughout the rest of the film, Buttgereit cuts back to this scene as the man’s corpse decays and is eaten by maggots. MONDAY. A man walks through the city streets, isolated and alone. He returns home, where he sits at a desk and writes a series of letters, placing them in envelopes. He telephones his workplace and quits his job. TUESDAY. A young man enters a videoshop, Videodrom, and selects a cassette. He initially picks up My Dinner with Andre but puts it down in favour of Vera, Todesengel Der Gestapo. He returns home and watches the film, a violent exploitation picture. He is interrupted by his girlfriend, who stands in front of the television and berates him. He pulls out a pistol and shoots her dead. However, this itself is revealed to be a scenario playing on a television set, in an apartment in which the resident has committed suicide by hanging. WEDNESDAY. The sky pours with rain. A young woman sits on a park bench next to a man who tells her of his marital problems: his wife bleeds heavily during intercourse, and though she has sought medical help, the man struggles to cope with this situation. The man is tired of the patience of his wife. The woman passes him a gun, the barrel of which he places in his mouth before pulling the trigger. THURSDAY. Travelling shots of a bridge over a motorway are accompanied by onscreen titles declaring the names, ages and occupations of people who have committed suicide by jumping from it. FRIDAY. A middle-aged woman watches her handsome younger neighbour jealously as he kisses his girlfriend. She receives a chain letter urging her to kill herself. She rips it up and instead lounges on her sofa, eating chocolates and drinking. She falls asleep, dreaming of being a child and walking in on her parents having sex in their bedroom. In the morning, she awakens and looks out of the window. The film cuts to the apartment of her handsome young neighbour. Inside, he and his girlfriend are dead, having committed suicide together.  SATURDAY. A young woman reads to a child, a girl, about the psychological characteristics of those who commit ‘amok-suicides’. Later, in front of a mirror, the young woman attaches a body rig to herself, to which she affixes a 16mm camera. Her point-of-view is shown as she ascends a staircase before committing her own ‘amok-suicide’, firing a gun into the crowd of a rock concert being held in an auditorium. SATURDAY. A young woman reads to a child, a girl, about the psychological characteristics of those who commit ‘amok-suicides’. Later, in front of a mirror, the young woman attaches a body rig to herself, to which she affixes a 16mm camera. Her point-of-view is shown as she ascends a staircase before committing her own ‘amok-suicide’, firing a gun into the crowd of a rock concert being held in an auditorium.

SUNDAY. A bare room; a mattress on the floor. On the mattress, a man sleeps. He awakens and glances about him. High-angle shots reinforce his isolation. He experiences what seem to be pangs of despair and anxiety. He weeps desperately, shrieking and crying, pounding the floor with his fists. He beats his head against the wall, the camera mimicking his movements, all the while weeping with despair. He becomes disoriented and weak, collapsing passively to the floor having seemingly succumbed to brain damage. The world swirls about him. The second feature film directed by Buttgereit, following Nekromantik in 1987, Der Todesking is highly ‘meta’, the story offering multiple layers of artifice and mixing colour footage with sepia-toned material, live action with animation, and presenting footage as ‘found’ material. Throughout the film, Buttgereit cuts repeatedly back to the shot of the naked man’s corpse, seemingly afloat in a void, as via time-lapse animation it decays, the flesh splitting and peeling from the bones, maggots squirming inside the chest cavity. With this depiction of decaying matter, Buttgereit seems to be alluding to Peter Greenaway’s use of decaying animal corpses in A Zed and Two Noughts (1985). The film has an episodic structure, its narrative presented as a series of vignettes depicting the suicides of a number of unrelated characters; each story takes place on a different day of the week, the days denoted by the audience via onscreen title cards. Each of the film’s stories is linked tangentially by a chain letter urging the recipient(s) to commit suicide. As Buttgereit has commented in interview, ‘Das ist ein Film in der Struktur einer Wocher, er fangt Montags an und hort Sonntags auf und jeden Tag sieht man’ (‘That is a film that adopts the structure of the week, beginning on Monday and ending on Sunday and showing the viewer all the days’) (Buttgereit, quoted in Kluge, 2012: 411).  ‘Der Tödesking’, the King of Death, is introduced in the film’s opening sequence as a crude character drawn by a young girl on a notepad. The camera looks over her shoulder as she writes ‘Der Tödesking’ at the top of the page and then sketches the character. The film returns to this girl in the closing sequence too, and to the camera she asserts that ‘This is the Death King. He makes people want to die’. The rest of the film may be interpreted as a product of this young girl’s macabre imagination; this interpretation is reinforced by the recurrence on the soundtrack of sounds of children’s voices as if playing on a playground – apparently the immediate context in which the girl is drawing the King of Death. The film closes on a shot of the King of Death seated on a chair with a baby at his feet, a visual metaphor for the relationship between life and death. The film opens with a title card bearing a quote from Pierre Francois Lacenaire, the 19th Century French murderer (of a transvestite, a bank teller and his own mother) who displayed no remorse about his crimes. Lacenaire was an aspiring poet; Der Todesking begins with a quote, translated into German, taken from the inscription beneath the frontispiece of Lacenaire’s Mémoires: ‘Was mich tötet, bleibt mein Geheimnis’ (translated in the subtitles as ‘That which kills me, remains a secret’). This enigmatic quote is given greater context in the full passage from Lacenaire’s book: ‘Il est un secret qui me tue, / Que je dérobe aux regards curieux, / Vous ne voyez ici que la statue, / L'âme se cache à tous les yeux’ (‘There is a secret that kills me / Which I hide from curious eyes / You will see here only the statue / The soul is hidden from every gaze’). The Lacenaire reference reinforces the theme of isolation and disconnection that characterises all of the characters in Der Todesking: within the despair of all of the characters seems to be their failure to ‘connect’ and the lack of any meaningful relationships whatsoever. ‘Der Tödesking’, the King of Death, is introduced in the film’s opening sequence as a crude character drawn by a young girl on a notepad. The camera looks over her shoulder as she writes ‘Der Tödesking’ at the top of the page and then sketches the character. The film returns to this girl in the closing sequence too, and to the camera she asserts that ‘This is the Death King. He makes people want to die’. The rest of the film may be interpreted as a product of this young girl’s macabre imagination; this interpretation is reinforced by the recurrence on the soundtrack of sounds of children’s voices as if playing on a playground – apparently the immediate context in which the girl is drawing the King of Death. The film closes on a shot of the King of Death seated on a chair with a baby at his feet, a visual metaphor for the relationship between life and death. The film opens with a title card bearing a quote from Pierre Francois Lacenaire, the 19th Century French murderer (of a transvestite, a bank teller and his own mother) who displayed no remorse about his crimes. Lacenaire was an aspiring poet; Der Todesking begins with a quote, translated into German, taken from the inscription beneath the frontispiece of Lacenaire’s Mémoires: ‘Was mich tötet, bleibt mein Geheimnis’ (translated in the subtitles as ‘That which kills me, remains a secret’). This enigmatic quote is given greater context in the full passage from Lacenaire’s book: ‘Il est un secret qui me tue, / Que je dérobe aux regards curieux, / Vous ne voyez ici que la statue, / L'âme se cache à tous les yeux’ (‘There is a secret that kills me / Which I hide from curious eyes / You will see here only the statue / The soul is hidden from every gaze’). The Lacenaire reference reinforces the theme of isolation and disconnection that characterises all of the characters in Der Todesking: within the despair of all of the characters seems to be their failure to ‘connect’ and the lack of any meaningful relationships whatsoever.

If the film’s subject matter is bleak, Buttgereit suggests that this is because during the production of both Nekromantik and Der Todesking ‘I was having a lot of experiences with death. A lot of my family members passed away during that time. So I was having death in my head, you could say, all of the time [….] It was a way to deal with all the problems I had during that time. So it was cathartic’ (Buttgereit, quoted in Edwards, 2017: 131).  Buttgereit has said that in Germany, it was essential that he was seen as an ‘artist’ first and foremost, rather than a horror/exploitation filmmaker, as this was ‘a way to survive and [….] get away with the stuff that I do’ (Buttgereit, quoted in Edwards, op cit.: 131-2). The episodic structure of Der Todesking and Buttgereit’s almost Brechtian use of footage of the decaying corpse throughout the picture invited comparisons with the work of Peter Greenaway and, in particular, Greenaway’s then-recent A Zed and Two Noughts and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989). Certainly, surprisingly, in the UK Der Todesking seemed to be received more as an ‘art’ film than a horror picture, the BBFC passing the film for home video classification without cuts (by Headpress in 1990, and Screen Edge in 1997), though the castration-by-shears in the Nazisploitation parody segment was pre-cut by the distributor, losing 4 seconds of footage. Given the BBFC’s outright hostility to both Nekromantik and Nekromantik 2 during this period, their acceptance of Der Todesking was quite astonishing. Buttgereit has said that in Germany, it was essential that he was seen as an ‘artist’ first and foremost, rather than a horror/exploitation filmmaker, as this was ‘a way to survive and [….] get away with the stuff that I do’ (Buttgereit, quoted in Edwards, op cit.: 131-2). The episodic structure of Der Todesking and Buttgereit’s almost Brechtian use of footage of the decaying corpse throughout the picture invited comparisons with the work of Peter Greenaway and, in particular, Greenaway’s then-recent A Zed and Two Noughts and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989). Certainly, surprisingly, in the UK Der Todesking seemed to be received more as an ‘art’ film than a horror picture, the BBFC passing the film for home video classification without cuts (by Headpress in 1990, and Screen Edge in 1997), though the castration-by-shears in the Nazisploitation parody segment was pre-cut by the distributor, losing 4 seconds of footage. Given the BBFC’s outright hostility to both Nekromantik and Nekromantik 2 during this period, their acceptance of Der Todesking was quite astonishing.

Though the art/exploitation distinction is largely a false dualism, in comparison with Buttgereit’s Nekromantik and its sequel it’s clear that Der Todesking has somewhat artistic aspirations. Buttgereit himself asserted that ‘This isn’t really a horror film. It’s more of an art film. I’m still not sure if it’s successful’ (Buttgereit, quoted in Szpunar, 2002: 23). In the midst of the various small stories of suicide, Buttgereit inserts animated time lapse shots of the man’s corpse decaying. Buttgereit intended these inserts to remind the viewer of the corporeality of the human subject: the inserts were ‘a way of getting away from these romanticized notions of suicide. You know, people killing themselves and going to Heaven and everything will be fine. I just wanted to show the plain basic truth that I experienced when I lost my mother. For example, that she is not there anymore and her body is falling to pieces’ (Buttgereit, quoted in Edwards, op cit.: 131).  The film features some clever use of filmmaking technique. In Monday’s segment, the young man who is shown taking a cocktail of pills in the bath is depicted in his apartment, isolated from the world. He has a goldfish that lives in a bowl on his desk, and the camera, fixed on a tripod, pans around the room several times, picking up the young man performing various tasks in different areas of the apartment as the light changes. It’s an ingenious way of denoting the passage of time whilst also emphasising the isolation of the man through connecting him visually – via his self-imposed entrapment within the apartment – with the goldfish in the bowl, his life a mass of repeated gestures and deadening routines. (With the rotating pan and its connotations, Buttgereit may very well be deliberately referencing the similar panning shot that concludes Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, 1974.) When the same young man takes a cocktail of pills whilst sitting in his bathtub, he slips away quietly and Buttgereit cuts symbolically to a shot of the goldfish, presumably dead, sinking to the bottom of its bowl. The film features some clever use of filmmaking technique. In Monday’s segment, the young man who is shown taking a cocktail of pills in the bath is depicted in his apartment, isolated from the world. He has a goldfish that lives in a bowl on his desk, and the camera, fixed on a tripod, pans around the room several times, picking up the young man performing various tasks in different areas of the apartment as the light changes. It’s an ingenious way of denoting the passage of time whilst also emphasising the isolation of the man through connecting him visually – via his self-imposed entrapment within the apartment – with the goldfish in the bowl, his life a mass of repeated gestures and deadening routines. (With the rotating pan and its connotations, Buttgereit may very well be deliberately referencing the similar panning shot that concludes Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, 1974.) When the same young man takes a cocktail of pills whilst sitting in his bathtub, he slips away quietly and Buttgereit cuts symbolically to a shot of the goldfish, presumably dead, sinking to the bottom of its bowl.

In Tuesday’s segment, the young man visiting the videoshop selects a videocassette titled Vera, Todesengel der Gestapo. The cover art, and the title itself, is clearly intended to parody Don Edmonds’ Nazisploitation ‘classic’, Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS (1975). Initially, the young man picks up Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981): fans of Buttgereit will of course remember that in Nekromantik 2 Mark and Monika go on a date to a cinema where they watch ‘Mon dejeuner avec Vera’, a parody of art cinema that references the Malle film. At home, the young man watches Vera, Todesengel der Gestapo: photographed in sepia tones, the film is a low-budget, graphic exploitation film. A man is shown tied to a wooden frame in a hut; a woman in a caricatured Nazi uniform approaches him with a pair of garden shears. In a vicious close-up, she severs his penis and testicles with the implement. The man’s viewing of the videotape is interrupted when his girlfriend walks into the apartment and chastises him for watching television. She stands in front of the screen, antagonising him further. He draws a pistol and first, hitting her in the head. He punches the photograph out of a frame and hangs the frame over the cranial matter that is splattered on the wall near the television. Buttgereit seems to be satirising the mindset, popular in Germany as much as the UK during the 1980s and 1990s, that video violence causes copycat violence. He further pulls the rug from beneath his audience by revealing that this entire scenario (from the young man entering the video shop to the murder of his girlfriend) is simply video material playing on a television in an apartment which, Buttgereit reveals, contains the body of someone who has hanged herself. (Buttgereit shows only the feet and lower legs of the suicided person, which can be seen through an open doorway, dangling in mid-air.) Rather than causing an explosion of violence directed towards someone else, this graphic video footage is revealed to have been the backdrop to a quiet suicide by hanging.  On Wednesday, the man on the park bench explains his predicament to a female stranger. His wife bleeds heavily during intercourse, he says, and though she has sought medical help, the doctors can find nothing wrong. The man’s wife is kind and tolerant, and it seems this patient attitude irks the man: ‘I couldn’t stand her kindness any longer’, he asserts, telling the woman that he ‘separated her [his wife’s] head from the body’. During this revelation, the film appears to suffer extreme gate weave, the image rolling across the screen. It’s a deliberate technique on the part of Buttgereit, another device designed to alienate the viewer in a Brechtian manner before the woman passes a gun to the man and he places it in his mouth before pulling the trigger. On Wednesday, the man on the park bench explains his predicament to a female stranger. His wife bleeds heavily during intercourse, he says, and though she has sought medical help, the doctors can find nothing wrong. The man’s wife is kind and tolerant, and it seems this patient attitude irks the man: ‘I couldn’t stand her kindness any longer’, he asserts, telling the woman that he ‘separated her [his wife’s] head from the body’. During this revelation, the film appears to suffer extreme gate weave, the image rolling across the screen. It’s a deliberate technique on the part of Buttgereit, another device designed to alienate the viewer in a Brechtian manner before the woman passes a gun to the man and he places it in his mouth before pulling the trigger.

Saturday’s episode is just as combative and self-referential. This instalment opens in what seems to be a projection booth in which footage is being screened. We are shown the footage: point-of-view shots from the perspective of someone carrying a gun. Another scene follows, the camera fixed in one location as, in a long shot, a young woman reads to a child about the psychological characteristics of those who commit ‘amok-suicides’. ‘Amok-suicides allow their instigators to escape from a “dead” life to a “living” death’, the young woman asserts. Soon, she is shown in another room, standing in front of a mirror as she fits a camera rig to her body and affixes a 16mm camera to it. Returning to the projection booth, we hear the projectionist assert, ‘Reel Two’. The film cuts to more film-within-a-film footage: we see from the point-of-view of the young woman as she climbs a staircase and enters an auditorium in which a rock concert is being held, firing a gun at the performers and then at the crowd. Shot in such a way as to suggest a ‘found’ depiction of violence being presented for investigators, in the manner of Ruggero Deodato’s 1979 picture Cannibal Holocaust, for example, the imagery in this scene references panics about ‘snuff’ footage and anxieties about mass killings and acts of random violence that still feel very contemporary, almost twenty years after Der Todesking was made.

Video

Surprisingly, Der Todesking was released in the UK on VHS uncut by the BBFC, though the distributor had already made a brief pre-cut of 4 seconds, trimming the image of the victim’s penis and testicles being mangled by the shears in the Nazisploitation footage. Surprisingly, Der Todesking was released in the UK on VHS uncut by the BBFC, though the distributor had already made a brief pre-cut of 4 seconds, trimming the image of the victim’s penis and testicles being mangled by the shears in the Nazisploitation footage.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation is very welcome, and follows the company’s previous Blu-ray releases of Nekromantik and Nekromantik 2 reviewed by us here). The presentation has been approved by Buttgereit and is apparently sourced from the original 16mm negative. The film takes up 28Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc and is uncut, running for 75:25 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Der Todesking is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The colour 16mm photography fares well here, with some very good fine detail present throughout. The image is crisp, and the grain structure of the film is coarse and organic, in line with the film’s origins as a 16mm production. This is communicated excellently via the encode to disc, which is robust. Colours are vibrant and naturalistic. Contrast is good, but given this is apparently a negative-source presentation, the tonal curves seem very sharp, with shadow detail descending into pure black quite quickly and, at the other end of the spectrum, highlights also sometimes seeming a little blown. Midtones have an excellent level of definition, however. Damage is present but organic: there are intermittent white scratches and flecks, suggesting debris on the negative. In all, it’s a very good, filmlike presentation of a 16mm picture.

Audio

Audio is presented in German via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. The film was post-synched and there’s a sense of alienation within the sound design that tallies with the film’s themes. The audio track is rich and clear. Optional English subtitles are included. These are easy to read. The subtitles contain one or two minor errors: for example, in Monday’s segment the young man telephones his workplace and asks to be connected to the personnel department (so that he may quit his job), but the subtitles translate this ‘personal department’.

Extras

On-disc extras include: On-disc extras include:

- An audio commentary with Jorg Buttgereit and Franz Rodenkirchen. The pair discuss the original intentions for the movie and reflect on its production, commenting in detail on the limitations facing them (eg, not enough film stock to shoot many scenes more than once, resulting in a very careful rehearsal process). They talk about the locations used in the film, such as the videoshop featured in the ‘Tuesday’ segment. It’s a lively track, filled with information. - ‘From Bundy to Lautreamont’ (36:26). Recorded at the Manchester Festival of Fantastic Films in 2016, this video piece features Buttgereit on stage, talking with film journalist Graham Rae. Buttgereit talks about his beginnings as a filmmaker, shooting small films on a Super 8 camera. He discusses the making of Nekromantik and his relationship with producer Manfred Jelinski. Buttgereit reflects in detail on his intentions with Der Todesking, and considers his use of quotations from Lacenaire and Lautreamont within the film. - ‘Todesmusik’ (10:32). Herman Kopp, who appears in Der Todesking as the victim in the ‘Monday’ segment and who composed the score for this film and the two Nekromantik pictures, talks about his relationship with music. He reflects on his score for Der Todesking and discusses some of the tracks used in the film. - ‘Skeleton Beneath the Skin’ (6:40). Graham Rae discusses a trend amongst online fans of Buttgereit’s films to get tattoos depicting images from Buttgereit’s films and shares footage of himself receiving a tattoo of ‘Der Tödesking’. This is accompanied by a Jorg Buttgereit Tattoo Gallery (104 images) containing photographs of Buttgereit-themed tattoos, including images from Der Todesking and other pictures by the director.

- ‘The Making of Der Todesking’ (16:20). This short featurette looks at the production of the film and is available with either an English soundtrack (which features comments from Buttgereit, in English, and a narrator) or a German soundtrack (which is more music-heavy). Clips from the finished film are interspersed with behind-the-scenes footage revealing how the travelling shot of the bridge was achieved and the special effects depicting the decaying corpse. - ‘The Letter’ (1:58). This feature contains the English-language chain letter insert used in Der Todesking’s English-language VHS releases. - ‘Eating the Corpse’ (9:43). Shot at the premiere of Der Todesking in 1990, this material is presented with a soundtrack of music from the film. - ‘Corpse Fucking Art’ (60:40). An exceptional documentary, ‘Corpse Fucking Art’ looks at the production of Nekromantik, Der Todesking and Nekromantik 2. It includes clips from the films interspersed with behind-the-scenes footage. Both an English-language soundtrack and a German-language soundtrack (with optional English subtitles) are offered. The former features a narrator’s comments accompanied by audio clips from interviews with Buttgereit (speaking in English). The latter includes different comments from Buttgereit. Buttgereit reflects candidly on his intentions with these three films, discussing their production histories and reflecting on his technique as a filmmaker. - Short Films: ‘Die Reise ins Licht’ (Manfred Jelinski, 1972); ‘Geliebter Wahnsinn’ (Manfred Jelinski, 1973); ‘Der Gollob’ (Jorg Buttgereit, 1983). ‘Die Reise ins Licht’ is presented with an optional commentary track from Jelinski (in English), in which Jelinski reflects on the writing and production of the short film. ‘Der Gollob’ also contains an optional commentary track from Buttgereit, also speaking in English. Buttgereit discusses the film’s themes and examines the making of this short film in detail. - Image Gallery (172 images). The gallery contains a mixture of black and white and colour photography, both onset stills and promotional images. - Trailer Gallery: Nekromantik (2:03); Der Todesking (2:26); Nekromantik 2 (1:08); Schramm (1:28). Retail copies of the film include a book and an audio CD containing an expanded version of the film’s soundtrack. Previous releases of the music for this film have only contained a handful of tracks. Arrow’s CD contains seventeen tracks, on the other hand.

Overall

Buttgereit’s films have always been quite ‘arty’, and this sometimes alienates horror/exploitation fans who come to the pictures hoping for more simple transgressive thrills. However, as Buttgereit has suggested, he felt that his films needed to be somewhat artistic in order to attempt to deflect the criticisms made by the authorities. Der Todesking is perhaps Buttgereit’s most ‘artful’ film. (The image in this film of the cranial matter splattered on the wall over which the murdered places a photo frame is perhaps an apt metaphor for Buttgereit’s career as a whole.) The picture contains references to both horror/exploitation films and art cinema (allusions are made to Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Ferrara’s Ms 45, Peter Greenaway, Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre, Don Edmonds’ Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS). In sum, it’s an exploration of a philosophy of suicide and murder, exploring the contextual issues that drive various individuals to take their own lives and the lives of others. Buttgereit seems to point the finger at social isolation: all of the characters lead sad, lonely lives, isolated in their despair. Their deaths grow out of this isolation and a strong sense of frustration. Henry David Thoreau wrote that ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation’, and Buttgereit’s film seems like an utter validation of this concept. Buttgereit’s films have always been quite ‘arty’, and this sometimes alienates horror/exploitation fans who come to the pictures hoping for more simple transgressive thrills. However, as Buttgereit has suggested, he felt that his films needed to be somewhat artistic in order to attempt to deflect the criticisms made by the authorities. Der Todesking is perhaps Buttgereit’s most ‘artful’ film. (The image in this film of the cranial matter splattered on the wall over which the murdered places a photo frame is perhaps an apt metaphor for Buttgereit’s career as a whole.) The picture contains references to both horror/exploitation films and art cinema (allusions are made to Hitchcock’s Rear Window, Ferrara’s Ms 45, Peter Greenaway, Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre, Don Edmonds’ Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS). In sum, it’s an exploration of a philosophy of suicide and murder, exploring the contextual issues that drive various individuals to take their own lives and the lives of others. Buttgereit seems to point the finger at social isolation: all of the characters lead sad, lonely lives, isolated in their despair. Their deaths grow out of this isolation and a strong sense of frustration. Henry David Thoreau wrote that ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation’, and Buttgereit’s film seems like an utter validation of this concept.

Like Buttgereit’s other pictures, Der Todesking is an acquired taste. It’s a bleak film, but it also has its elements of black humour – much like the Nekromantik pictures and Schramm, which is perhaps Buttgereit’s best picture. Buttgereit’s films are a love or hate proposition; it’s hard to maintain a non-partisan middleground in relation to his cinema. Arrow’s presentation of Der Todesking is very pleasing. Damage is present but it’s organic and true to source, the presentation being satisfyingly filmlike. The main feature is also supported by some excellent contextual material, not least of which is the superb documentary ‘Corpse Fucking Art’ – here presented in two variants (the English version and the German presentation). This release is a great pleasure and one that Buttgereit fans have been waiting for (Der Todesking has been difficult to see in the digital age; speaking personally, this new release enables me to retire my old Screen Edge videocassette). References: Edwards, Matthew, 2017: Twisted Visions: Interviews with Cult Horror Filmmakers. London: McFarland & Co Kluge, Alexander, 2012: ‘Ein subversive Romantiker’. Schulte, Christian (ed), 2012: Die Schrift an der Wander – Alexander Kluge: Rohstoffe und Materialien. Vienna University Press: 389-414 Szpunar, John, 2002: ‘Seven Drunken Nights: Down in the Dirt at the Cine Muerte Film Festival’. In: Kerekes, David (ed), 2002: Headpress 23: Funhouse. Manchester: Headpress/Critical Vision: 4-24 Click images to enlarge:

|

|||||

|