|

|

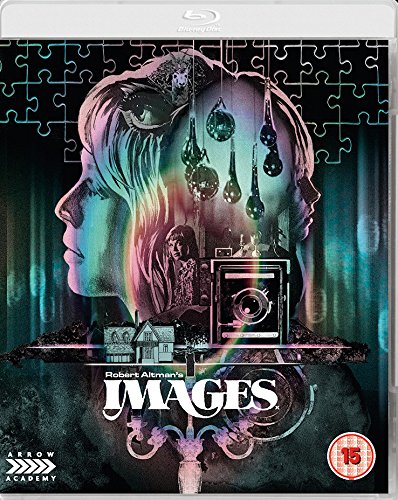

Images (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th March 2018). |

|

The Film

Images (Robert Altman, 1972) Images (Robert Altman, 1972)

Cathryn (Susannah York) is writing a children’s book, In Search of Unicorns. She is interrupted by a telephone call from her friend Joan, who complains about her ex-husband. However, part-way through the phone call, another woman’s voice comes on the line and warns Cathryn that her husband Hugh (Rene Auberjonois) is with another woman. The woman is persistent and calls Cathryn repeatedly; Cathryn responds by taking all the telephones off the hook. When Hugh returns home, Cathryn confronts him. Hugh tells Cathryn he was at a work function and can prove it. He kisses Cathryn, but she opens her eyes to find herself being kissed by Rene (Marcel Bozzuffi), her former lover who died in a plane crash three years earlier. Cathryn screams and flees into the arms of Hugh, who comes to her aid. Rene is nowhere to be seen. Hugh and Cathryn decide to spend time at her family home in the countryside, Green Cove. There, whilst alone, she hears a woman’s voice calling her name and phantom footsteps on the floor above. She also sees Rene once again and converses with him, but he disappears again. Outside the house, she encounters her doppelgänger too. More ghosts from the past arrive in the form of Marcel (Hugh Millais), a former lover of Susannah’s. Marcel is accompanied by his daughter Susannah (Cathryn Harrison). Behind Hugh’s back, Marcel aggressively tries to seduce Susannah; each time, she initially resists but eventually relents before pulling herself away from Marcel. Left alone in the house, Susannah is confronted by Rene. With her husband’s shotgun, she shoots the ghost but discovers that instead, she has destroyed Hugh’s large format camera. When Hugh reveals that he must leave Green Cove on a work-related trip, Susannah is left alone in the house. Marcel arrives and tries to force himself on Susannah; she reacts by stabbing him to death. However, the next day she talks to Cathryn, who tells Susannah that Marcel was alive and well last night. Cathryn drives Susannah home and is both dismayed and relieved to discover that she didn’t kill Marcel.  However, when she returns to Green Cove, Cathryn finds the bodies of Rene and Marcel still on the floor. She makes a decision to flee Green Cove in her car and return to her home in the city. However, when she returns to Green Cove, Cathryn finds the bodies of Rene and Marcel still on the floor. She makes a decision to flee Green Cove in her car and return to her home in the city.

Sandwiched, in terms of its place in the career of director Robert Altman, between 1971’s McCabe and Mrs Miller and 1973’s The Long Goodbye, Images (1972) differs from those two pictures by refusing to conform to a standard Hollywood generic template (no matter how ironically these templates are presented in both McCabe and Mrs Miller and The Long Goodbye). Images looks back to Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park (1969) and forwards to the later picture 3 Women (1977) in terms of its multilayered, experimental technique and its focus on women and women’s roles in society. As Robert Philip Kolker has asserted, Altman’s films about women (That Cold Day in the Park, Images, 3 Women) ‘must be understood as films about women from the point of view of a particular male’ (Kolker, 2011: 411). Reflecting on this viewpoint, Robin Wood suggested in Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan that 3 Women explores a relevant issue (‘that women conditioned by our culture, however seemingly independent, might not be able to escape entrapment in familial roles and structures’) but simplistically depicts the female characters ‘as victims, yes, but primarily of their own innate stupidity’ – that Altman’s conception of woman is ‘as victim’ and defined by ‘masochism and self-punishment’ – which makes them part of the same stream of ‘women’s pictures’ as films like Looking for Mr Goodbar (Wood, 2003: np). Likewise, Images doesn’t quite break gender stereotypes. Cathryn is depicted as a woman on the verge of hysteria, her emotional crisis a result of her conflicted sexuality, implied promiscuity and confusion about her roles as wife and lover to Hugh, Rene and Marcel (‘Don’t give me a baby’, she tells Marcel during the throes of passion; ’I want a baby’, she pleads to Hugh during a similar embrace; earlier, she has told Rene’s ‘ghost’, ‘All I ever wanted from you was a baby'). She is torn in her dealings with Marcel, who attempts to seduce her roughly a number of times in the film; each time, Cathryn resists but eventually relents, kissing Marcel passionately before pulling away.  Altman suggested that the film, which he planned in the 1960s, was based on a simple premise: the notion that one could be ‘sitting on a bed and you’re talking to your wife, who’s in the bathroom. And you’re talking away and she comes out and it’s an entirely different woman you’re talking to. What do you do? Do you continue the conversation and think, “I’m wrong,” or do you cover and think this is in your mind? Or do you throw her out of the house because she is a stranger?’ (Altman, in Zuckoff, 2009: 241-2). Altman asserted that he didn’t deliberately set out to ‘do anything about schizophrenia’ but later realised he was ‘pretty accurate in it. It was an instinctive kind of thing’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.). Altman suggested that the film, which he planned in the 1960s, was based on a simple premise: the notion that one could be ‘sitting on a bed and you’re talking to your wife, who’s in the bathroom. And you’re talking away and she comes out and it’s an entirely different woman you’re talking to. What do you do? Do you continue the conversation and think, “I’m wrong,” or do you cover and think this is in your mind? Or do you throw her out of the house because she is a stranger?’ (Altman, in Zuckoff, 2009: 241-2). Altman asserted that he didn’t deliberately set out to ‘do anything about schizophrenia’ but later realised he was ‘pretty accurate in it. It was an instinctive kind of thing’ (Altman, quoted in ibid.).

Cathryn finds herself ‘haunted’ by Rene, her former husband who died in an airplane crash three years prior to the narrative. Eventually, like Golyadkin in Dostoevsky’s The Double (1846) or the titular protagonist of Poe’s ‘William Wilson’ (1839), Cathryn is eventually haunted by herself - or rather, a projection of herself which fractures her sense of identity. Having successfully ‘killed’ Rene and Marcel, Cathryn decides that there is only one solution to the ‘problem’ of her double, which seems to be framed as an externalisation of those aspects of Cathryn’s self that she would prefer to forget, her proletarian sexuality that has been repressed (her desire for the kind of rough sex represented via her encounters with Marcel) within her marriage to Hugh; that solution is to kill her too. Images combines a theme of doubling with an ambiguous depiction of Cathryn’s ‘hallucinations’: these, such as the appearance of Cathryn’s dead lover Rene, are depicted in concrete fashion for the viewer, so that ‘reality’ and ‘illusion’ overlap within the film’s diegesis and become indistinguishable. As this description might suggest, Altman’s film bears the heavy influence of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1965), alongside the work of Joseph Losey (in particular, The Accident, 1967). In interview, Altman suggested that ‘I’m sure that film [Persona] was largely responsible for Images and 3 Women. There was a power in Persona, and I think that came from the fact that one woman talked and the other didn’t […] We know the situation, and if we know all these situations, then we have a certain expectation of what these situations are going to bring. The trick, to me, is not to bring that expectation’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, 2011: 3).  As if to reinforce the theme of doubling, Altman employs an interesting technique of having his characters retain the forenames of the film’s actors, but swapping these names amongst the cast - so Marcel Bozzuffi plays Rene; Rene Auberjonois plays Hugh; Hugh Millais plays Marcel; Cathryn Harrison plays Susannah; Susannah York plays Cathryn. The film contains three depictions of masculinity. Hugh is uptight and seemingly repressed, fascinated with death and his visual sense: he makes a tableau of a dead bird, photographing the scene with his large format camera - the camera that Cathryn destroys accidentally when she shoots the ‘ghost’ of Rene. Marcel is lecherous, chauvinistic and rough in his attempts to seduce Cathryn; for her part, Cathryn responds ambiguously to Marcel’s aggressive advances. Meanwhile, Rene taunts Cathryn about what he suggests is her promiscuity. As if to reinforce the theme of doubling, Altman employs an interesting technique of having his characters retain the forenames of the film’s actors, but swapping these names amongst the cast - so Marcel Bozzuffi plays Rene; Rene Auberjonois plays Hugh; Hugh Millais plays Marcel; Cathryn Harrison plays Susannah; Susannah York plays Cathryn. The film contains three depictions of masculinity. Hugh is uptight and seemingly repressed, fascinated with death and his visual sense: he makes a tableau of a dead bird, photographing the scene with his large format camera - the camera that Cathryn destroys accidentally when she shoots the ‘ghost’ of Rene. Marcel is lecherous, chauvinistic and rough in his attempts to seduce Cathryn; for her part, Cathryn responds ambiguously to Marcel’s aggressive advances. Meanwhile, Rene taunts Cathryn about what he suggests is her promiscuity.

Images was shot in County Wicklow in Ireland, though Altman reputedly originally intended for the picture to be made in Vancouver with Sandy Dennis - and that project eventually evolved into That Cold Day in the Park, the idea for Images being shelved until a later date. For a while, Altman toyed with the idea of making the picture in Milan with Sophia Loren in the lead role (see Niemi, 2016: np; Thompson, op cit.: 4). Altman saw Susannah York in Jane Eyre (Delbert Mann, 1970) and, feeling she was right for the lead role in Images, approached her with the part. York agreed reluctantly, after Altman flew from LA to Corfu to press her to accept the role (ibid.). The film, which had struggled to find financing, was funded by Hemdale; during preproduction, York discovered she was pregnant and almost dropped out of the film, but Altman persuaded her to stay with the project (ibid.). In Search of Unicorns, a children’s story that York was writing which Thompson described as ‘a kind of kindergarten Lord of the Rings’, perhaps for her own unborn child, was worked into the narrative via the depiction of Cathryn as a writer of books for children (Altman, quoted in Thompson, op cit.: 5). The film begins with Cathryn narrating the opening lines from the story; the narration returns at various points, the children’s story seeming to have relevance for the diegesis of the film. The County Wicklow locations work to the film’s advantage, the rugged and desolate landscape becoming a metaphor for Cathryn’s fragile mind. Altman suggested that he chose County Wicklow because he wanted to give the film ‘a non-real, English-speaking atmosphere, and Ireland in the wintertime gave me those vistas that you wouldn’t immediately recognize’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, op cit.: 5).  Ultimately, Images belongs to that small group of films made during the 1970s which focus on women going quietly insane, usually in the countryside - often the English, or Irish, countryside at that. Repressed sexuality is a theme throughout most, if not all, of these films. This subgenre owes much to Bergman’s Persona and includes the likes of James Kenelm Clarke’s Expose/The House on Straw Hill (1976) and, to some extent, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972). (Rene’s death-by-shotgun-blast-to-the-abdomen in Images is depicted in a Peckinpah-esque explosion of slow-motion grue.) There are American and Canadian variations too, of course, including William Fruet’s Death Weekend (1976) and Frederick Fiedel’s Axe (1974). Similarities could also be drawn between these pictures and the ‘woman-in-peril’ subtype of thrilling all’italiana pictures (Italian-style thrillers) such as Sergio Martino’s Tutti i colori del buio (All the Colours of the Dark/They’re Coming to Get You, 1972) and Lucio Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, 1971). In many of these films, the rural landscape becomes symbolically charged, a Freudian space in which the female protagonist encounters various spectres and/or doppelgängers which channel and represent her own repression; in this alien landscape, sex and violence become intertwined, virtually indistinguishable, and the past threatens to resurface and erode present relationships. As in so many films of the 1970s, the telephone becomes a symbol of this alienation, the first hints of Cathryn’s dislocation and mental deterioration appearing when Cathryn is on the the telephone to her friend Joan in the film’s opening sequence and hears another voice, a taunting female voice, which tells Cathryn that Hugh is with ‘a girl’. Ultimately, Images belongs to that small group of films made during the 1970s which focus on women going quietly insane, usually in the countryside - often the English, or Irish, countryside at that. Repressed sexuality is a theme throughout most, if not all, of these films. This subgenre owes much to Bergman’s Persona and includes the likes of James Kenelm Clarke’s Expose/The House on Straw Hill (1976) and, to some extent, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972). (Rene’s death-by-shotgun-blast-to-the-abdomen in Images is depicted in a Peckinpah-esque explosion of slow-motion grue.) There are American and Canadian variations too, of course, including William Fruet’s Death Weekend (1976) and Frederick Fiedel’s Axe (1974). Similarities could also be drawn between these pictures and the ‘woman-in-peril’ subtype of thrilling all’italiana pictures (Italian-style thrillers) such as Sergio Martino’s Tutti i colori del buio (All the Colours of the Dark/They’re Coming to Get You, 1972) and Lucio Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, 1971). In many of these films, the rural landscape becomes symbolically charged, a Freudian space in which the female protagonist encounters various spectres and/or doppelgängers which channel and represent her own repression; in this alien landscape, sex and violence become intertwined, virtually indistinguishable, and the past threatens to resurface and erode present relationships. As in so many films of the 1970s, the telephone becomes a symbol of this alienation, the first hints of Cathryn’s dislocation and mental deterioration appearing when Cathryn is on the the telephone to her friend Joan in the film’s opening sequence and hears another voice, a taunting female voice, which tells Cathryn that Hugh is with ‘a girl’.

Images garnered praise for Susannah York’s performance in particular, with York winning Best Actress at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, where Images was also nominated for the Grand Prix (the Palme d’Or), losing out to Francesco Rosi’s Il casto Mattei (The Mattei Affair, 1972) and Elio Petri’s La classe operaia va in paradiso (The Working Class Go to Heaven, 1972) - two Italian films which shared the award. Elsewhere, the film divided critics, with Howard Thompson writing in The New York Times that Images is a ‘clanging, pretentious, tricked-up exercise’, suggesting that the film buries its lack of a ‘progressive story line’ within ‘a technical smoke screen’ (Thompson, quoted in Zuckoff, 2009: 241). Perhaps sensing these kinds of reactions to Images, Robert Duvall turned the script down because he felt that it ‘wasn’t right’, and Altman suggested that Duvall didn’t ‘get it’, suggesting Duvall needed his wife to explain it; ‘Bullshit’, Duvall later reflected, ‘I don’t need my wife to explain it. I got it, I just didn’t like it’ (Duvall, quoted in ibid.: 242).

Video

Taking up 29.9Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, Images is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Images is uncut, with a running time of 101:12 mins. Taking up 29.9Gb of space on its Blu-ray disc, Images is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The film is presented in its intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Images is uncut, with a running time of 101:12 mins.

The colour 35mm photography is presented very well on this Blu-ray release, which uses as its basis a new 4k scan of the film’s negative. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond has suggested that he and Altman came up with the idea of using a combination of zoom lenses and mobile camerawork to represent Cathryn’s mental and emotional instability: ‘On Images, when we wanted to have something strange going on, because the woman is crazy, we decided to do this thing—zooming and moving sideways. And zooming, and dolling sideways. Or zooming forward’ (Zsigmond, quoted in Zuckoff, op cit.: 253). Talking about the film’s visual style, Altman reflected that he was ‘always attracted to reflections and images through glass, anything that destroys then actual image and puts different layers of reality on it. And the camera played a key role in the film. The actors even played to it. The husband [Rene] has his own camera, which he uses to look at her [Cathryn], after which she’d look at our camera’ (Altman, quoted in Thompson, op cit.: 29). The film’s autumnal colour palette, dominated by drab browns and greens similar to John Coquillon’s photography for Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, is represented very well here. Damage is limited to a few small flecks and specks. Contrast levels are very good, with rich midtones being present throughout the presentation; these are accompanied by some deep, rich blacks. Low light scenes, of which there are quite a few, fare nicely. Detail is consistently good throughout, a very pleasing level of fine detail present in close-ups. The grain structure of 35mm film is consistently present too. It’s a pleasing, film-like presentation that is carried through a solid encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track with accompanying optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The film’s haunting, experimental soundtrack was composed by John Williams and combines strings with haunting, atonal percussion (performed by Stomu Yamashta). The audio track is fine, displaying good range, and is clean and clear throughout. The subtitles are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary by Sam Deighan and Kat Ellinger. Critics Deighan and Ellinger suggest the film is a ‘lesser known’ picture by Altman, though I’m not sure that this label is true amongst cinephiles; however, casual film fans might not have heard of Images. Ellinger picks up on some of the subtle occult symbolism within the mise-en-scene of the opening sequence. Ellinger also talks about the moment in which Cathryn bites the apple and rejects it as being rooted in Altman’s research into schizophrenia, though on the other hand most of the published interviews with Altman suggest that Altman steadfastly refused to research the traits associated with schizophrenia and some suggest he only became cognisant of the similarities between Cathryn’s behaviour and the experiences of schizophrenics after the film was released. Altman was sometimes quietly provocative in interviews, so it's hard to know which of these positions is the most accurate. Deighan relates Images to Gothic ‘women’s films’ of the 1950s and 1960s, from Psycho to Let’s Scare Jessica to Death. - A selected scene commentary by Robert Altman (35:52). Taken from a previous release, this feature sees Altman providing some comments over a few of the film’s sequences, including (i) the opening sequence, (ii) the scene in which Hugh returns home and Cathryn mistakes him from Marcel, (iii) the sequence in which Hugh dresses his still life featuring the mounted stag’s head on a bed of leaves, (iv) the scene in which Cathryn converses with Rene and strikes him, realising she can hurt him; (v) the scene in which Marcel forces himself upon Cathryn in the pantry and the ‘ghost’ of Rene mocks her; (vi) a scene featuring Cathryn walking through the countryside; (vii) Cathryn’s ‘murder’ of Rene; and (viii) the final sequence, depicting Cathryn’s flight from Green Cove. Altman foregrounds some of the foreshadowing within the mise-en-scene and talks about his ‘instinctual’ approach to filmmaking. Altman’s comments sometimes dry up and he resorts to describing what’s on screen, but nevertheless there’s some fascinating insight into his approach to filmmaking. - ‘Imagining Images’ (24:31). This featurette, which has appeared on one of the film’s earlier DVD releases, sees Altman and Zsigmond talking about the film, reflecting on its genesis and production and discussing specific aspects of the filmmaking techniques employed in the picture. - Interview with Cathryn Harrison (6:04). Harrison discusses how she got the role in Images and discusses the shooting of her scenes. - Appreciation by Stephen Thrower (32:26). Thrower contextualises the film and provides a cogent analysis of its themes. He talks about Altman’s difficulties getting Images produced, discusses its relationship with Persona and reflects on its place within the group of films Hemdale made during the 1960s and 1970s. Thrower’s comments are characteristically well-researched and - Trailer (3:13).

Overall

Images is an interesting film, one of a number of pictures of the 1970s that seem shaped by the influence of Bergman’s Persona, whether directly or via osmosis. Images belongs to a lineage within Altman’s career which begins with That Cold Day in the Park and continues through to 3 Women: films which feature female protagonists, and which become increasingly experimental and abstract. Like those other pictures, Images is a divisive film. Images is an interesting film, one of a number of pictures of the 1970s that seem shaped by the influence of Bergman’s Persona, whether directly or via osmosis. Images belongs to a lineage within Altman’s career which begins with That Cold Day in the Park and continues through to 3 Women: films which feature female protagonists, and which become increasingly experimental and abstract. Like those other pictures, Images is a divisive film.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of images contains a very pleasing presentation of the main feature. The image is solid and filmlike, and audio is fine too. The film itself is accompanied by some good contextual material. Of the new content, Stephen Thrower’s interview stands out as being particularly well-researched and carefully-written. This is an excellent release of a very strong film from a consistently interesting period in Altman’s filmography. References: Kolker, Robert Phillip, 2011: A Cinema of Loneliness. Oxford University Press (Revised Edition) Zuckoff, Mitchell, 2009: Robert Altman: The Oral Biography. New York: Alfred A Knopf Niemi, Robert, 2016: The Cinema of Robert Altman: Hollywood Maverick. Columbia University Press Thompson, David, 2011: Altman on Altman. London: Faber & Faber Wood, Robin, 2003: Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan… and Beyond. Columbia University Press (Revised Edition) Click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|