|

|

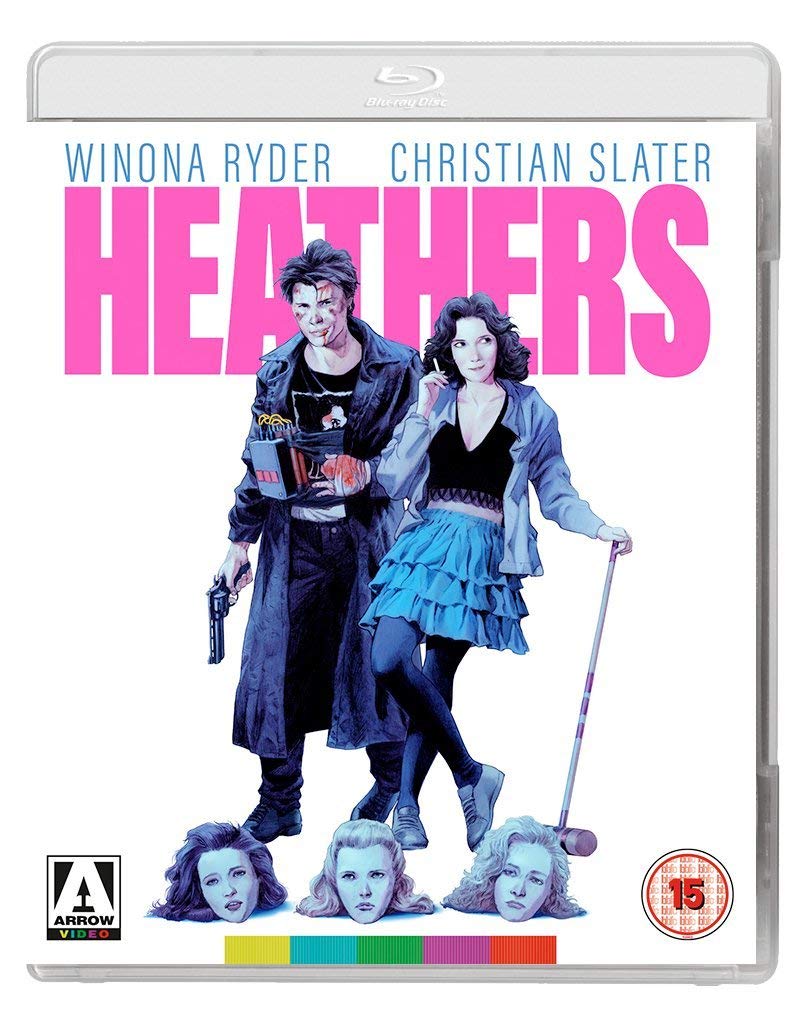

Heathers (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th September 2018). |

|

The Film

Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1989) Heathers (Michael Lehmann, 1989)

Having separated herself from her childhood friend Betty Finn (Renee Estevez), Veronica (Winona Ryder) has allied herself with the Heathers, the self-described ‘most powerful clique in school’ – Wesberburg High. The Heathers consist of three young women who share the same first name: queen bee Heather Chandler (Kim Walker); cheerleader Heather McNamara (Lisanne Falk); and the slightly troubled but no less bitchy Heather Duke (Shannen Doherty). The Heathers enlist Veronica’s help in enacting their cruel pranks on fellow students, such as forging a note suggesting that jock Kurt Kelly (Lance Fenton) has a crush on frumpy Martha ‘Dumptruck’ Dunnstock (Carrie Lynn). Veronica’s eye is caught by a new arrival at the school, Jason ‘JD’ Dean (Christian Slater), who soon puts two bullies – Kurt and his buddy Ram (Patrick Labyorteaux) – in their place using a gun loaded with blanks. After Heather Chandler takes Veronica to a frat party where Veronica is nearly sexually assaulted, she vows to teach Heather Chandler a lesson. ‘I’d like to see Heather Chandler puke her guts out’, Veronica tells JD. JD makes Veronica’s wish come true, mixing a drink for Heather Chandler that, unbeknownst to Veronica, contains drain cleaner. To Veronica’s surprise, Heather Chandler expires dramatically, falling face first through a glass coffee table. JD persuades Veronica to forge a suicide note.  Unexpectedly, Heather’s suicide note is praised by the staff at the school, and the event is even covered by the television news. JD notes that ironically, after her death Heather Chandler has become ‘more popular than ever now’. When Ram spreads a rumour around the school that he and Kurt had a threesome with Veronica, JD develops a plan to rid the school of the two jocks. Telling Veronica his gun is loaded with blanks, he asks her to lure them to the woods where the pair strip off in anticipation of having sex with Veronica. There, JD shoots and kills the pair, staging the scene so that it looks like a lovers’ suicide pact and planting around the bodies items intended to consolidate the idea that Kurt and Ram were repressed homosexuals – including ‘an issue of Stud Puppy, a candy dish, a Joan Crawford postcard’ and a bottle of mineral water. Unexpectedly, Heather’s suicide note is praised by the staff at the school, and the event is even covered by the television news. JD notes that ironically, after her death Heather Chandler has become ‘more popular than ever now’. When Ram spreads a rumour around the school that he and Kurt had a threesome with Veronica, JD develops a plan to rid the school of the two jocks. Telling Veronica his gun is loaded with blanks, he asks her to lure them to the woods where the pair strip off in anticipation of having sex with Veronica. There, JD shoots and kills the pair, staging the scene so that it looks like a lovers’ suicide pact and planting around the bodies items intended to consolidate the idea that Kurt and Ram were repressed homosexuals – including ‘an issue of Stud Puppy, a candy dish, a Joan Crawford postcard’ and a bottle of mineral water.

Veronica begins to see JD’s murderous nature for what it is, and she attempts to rekindle her friendship with Betty Fine. As JD plots a murderous end to a pep rally staged by the school’s teachers, which involves a round of explosives set in the boiler room of the building, Veronica tries to find a way to stop his destructive rampage. The 1980s seemed to be the era of the American ‘coming of age’ picture; the latter half of the decade produced many iconic variations on this theme, including Rob Reiner’s Stand By Me (1986) and John Hughes’ The Breakfast Club (1985). Released in the last year of the decade, and premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in the same year as Steven Soderbergh’s breakthrough indie feature sex, lies and videotape, like Soderbergh’s picture Michael Lehmann’s Heathers became a key film of ‘Generation X’, rejecting through black humour and violence the essentially warm view of American adolescence that had defined John Hughes’ youth pictures, for example, and ushering in the nihilism of Nirvana’s Nevermind in 1991, the music video for ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ seemingly paying homage to Lehmann’s picture. In many ways, Heathers invited comparison with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and its memorably metonymic opening sequence depicting a suburban idyll disrupted by the sudden collapse of a middle-aged man and the camera’s slow journey below ground towards the seemingly threatening insects that crawl beneath the well-kept gardens and white picket fences.  The opening sequence of Heathers is comparable to that of Blue Velvet, in the sense that both films establish their focus on the tensions that exist beneath the surface of a suburban idyll. Heathers opens with a sweet rendition by Syd Straw of ‘Que sera sera’ on the soundtrack as the camera shows us images of privilege: the Heathers playing croquet in a beautiful garden. However, the Heathers demonstrate their lack of respect for others and their surroundings by trampling over a flowerbed. They strike the croquet balls with their mallets, and a cut reveals that their target is Veronica, who has been buried up to her neck in the lawn. Brian Yuzna’s Society, also released in 1989, has a similar opening sequence as, on the soundtrack, we are presented with a variation of the Eton Boating Song. Like Yuzna’s picture, Heathers is about ‘fitting in’ and an idea of a desire to conform leading to a level of cruelty that would make Zimbardo wince. When JD first meets with Veronica, she tells him ‘I don’t really like my friends’. ‘Yeah, I don’t really like your friends either’, he responds. ‘It’s just, like, there are people I work with, and our job is being popular and shit’, she tells him dryly. When the Heathers, and Kurt and Ram, are found dead, their deaths-by-apparent-suicide turn these bullies into school heroes: in one of her diary entries, Veronica notes that ‘my teenage angst has a body count [….] Everybody’s sad, but it’s a weird kind of sad. Suicide gave Heather depth, Kurt a soul, Ram a brain [….] Are we going to prom or hell?’ When Martha Dunnstock attempts to commit suicide by walking into traffic, Heather McNamara reasons that it is simply ‘another case of a geek trying to imitate the popular people of the school and failing miserably’. The opening sequence of Heathers is comparable to that of Blue Velvet, in the sense that both films establish their focus on the tensions that exist beneath the surface of a suburban idyll. Heathers opens with a sweet rendition by Syd Straw of ‘Que sera sera’ on the soundtrack as the camera shows us images of privilege: the Heathers playing croquet in a beautiful garden. However, the Heathers demonstrate their lack of respect for others and their surroundings by trampling over a flowerbed. They strike the croquet balls with their mallets, and a cut reveals that their target is Veronica, who has been buried up to her neck in the lawn. Brian Yuzna’s Society, also released in 1989, has a similar opening sequence as, on the soundtrack, we are presented with a variation of the Eton Boating Song. Like Yuzna’s picture, Heathers is about ‘fitting in’ and an idea of a desire to conform leading to a level of cruelty that would make Zimbardo wince. When JD first meets with Veronica, she tells him ‘I don’t really like my friends’. ‘Yeah, I don’t really like your friends either’, he responds. ‘It’s just, like, there are people I work with, and our job is being popular and shit’, she tells him dryly. When the Heathers, and Kurt and Ram, are found dead, their deaths-by-apparent-suicide turn these bullies into school heroes: in one of her diary entries, Veronica notes that ‘my teenage angst has a body count [….] Everybody’s sad, but it’s a weird kind of sad. Suicide gave Heather depth, Kurt a soul, Ram a brain [….] Are we going to prom or hell?’ When Martha Dunnstock attempts to commit suicide by walking into traffic, Heather McNamara reasons that it is simply ‘another case of a geek trying to imitate the popular people of the school and failing miserably’.

One of the crucial aspects of Heathers is the dialogue by writer Daniel Waters, which is always on-point and loaded with sharp lines that fans of the film quote endlessly. Individual lines like Heather Chandler’s exclamative ‘Fuck me gently with a chain saw’ are often quoted by the film’s fans, but ‘What’s your damage?’ is the refrain heard throughout the film, a line delivered both as a query and as a challenge. (It’s a line that seems constructed to be part of a metafictional call and response with R Lee Ermey’s assertion ‘What’s your major malfunction, numbnuts?’ in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, released just two years earlier.) As Emanuel Levy notes, the youth slang employed in Waters’ script for the film ‘was made up, since the writer believed that duplicating actual teen-age slang would invite obsolescence for the film’ (Levy, 1999: 266). This dialogue is sometimes deliriously un-PC, however. ‘Doesn’t this cafeteria have a “no fags allowed” rule?’, Kurt asks JD in an attempt to intimidate him. ‘They seem to have an open door policy for assholes though, don’t they?’, JD responds. One of the crucial aspects of Heathers is the dialogue by writer Daniel Waters, which is always on-point and loaded with sharp lines that fans of the film quote endlessly. Individual lines like Heather Chandler’s exclamative ‘Fuck me gently with a chain saw’ are often quoted by the film’s fans, but ‘What’s your damage?’ is the refrain heard throughout the film, a line delivered both as a query and as a challenge. (It’s a line that seems constructed to be part of a metafictional call and response with R Lee Ermey’s assertion ‘What’s your major malfunction, numbnuts?’ in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, released just two years earlier.) As Emanuel Levy notes, the youth slang employed in Waters’ script for the film ‘was made up, since the writer believed that duplicating actual teen-age slang would invite obsolescence for the film’ (Levy, 1999: 266). This dialogue is sometimes deliriously un-PC, however. ‘Doesn’t this cafeteria have a “no fags allowed” rule?’, Kurt asks JD in an attempt to intimidate him. ‘They seem to have an open door policy for assholes though, don’t they?’, JD responds.

In the world of Heathers, authority is either absent or opened up to ridicule. Parents are disengaged from the lives of their children: we see Veronica’s parents briefly, and they display little interest in their daughter; and JD’s father is mostly absent, though when he appears he gleefully shares with Veronica tales of how he has dispatched his competitors and others who have obstructed his business dealings – including JD’s mother, who walked into a building that JD’s father had scheduled for demolition using explosives. A priest at Heather Chandler’s funeral launches into a bizarrely off-piste rant against ‘MTV video games’, which he blames for Heather’s apparent suicide before telling the assembled young people to ‘get in touch with that righteous dude [Christ] who can solve your problems’. The teachers at the school are no better: they are out of touch with the students, displaying no regard for them. After Heather Chandler is found dead, the staff of Westerburg High hold a meeting; some of the staff suggest the school should schedule a day off as a mark of mourning for the deceased Heather, but the Principal pooh-poohs this idea, suggesting however that ‘I’d be willing to go half a day for a cheerleader’. A female teacher, Pauline Fleming (Penelope Milford), expresses a belief that the faculty should feel more distress at Heather Chandler’s apparent suicide and find a way of channeling their sense of grief; in response, the principal tells her dryly to ‘tell us when your shuttle lands’. The students are even less sympathetic, and when Pauline tries to get her class to talk about their emotional responses to Heather’s death, one of the students asks her pithily, ‘Are we gonna be tested on this?’  Winona Ryder was advised not to take the role of Veronica lest it destroy her career (Goodall, 1998). However, Ryder was drawn to the project by the sharp dialogue in Daniel Waters’ script and the sense that Veronica was like ‘a sort of Humphrey Bogart role, a part for a forty-eight year old man’ (Ryder, quoted in ibid.). Ironically, Veronica is arguably the most memorable role in Ryder’s body of work – perhaps rivalled only by her parts in Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites (1994) and her performance as Abigail Williams in Nicholas Hytner’s 1996 adaptation of The Crucible. Winona Ryder was advised not to take the role of Veronica lest it destroy her career (Goodall, 1998). However, Ryder was drawn to the project by the sharp dialogue in Daniel Waters’ script and the sense that Veronica was like ‘a sort of Humphrey Bogart role, a part for a forty-eight year old man’ (Ryder, quoted in ibid.). Ironically, Veronica is arguably the most memorable role in Ryder’s body of work – perhaps rivalled only by her parts in Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites (1994) and her performance as Abigail Williams in Nicholas Hytner’s 1996 adaptation of The Crucible.

Veronica begins the film as an ally of the Heathers, having abandoned her long-standing friendship with nerdy Betty Finn in order to be a part of the self-described ‘most powerful clique in the school’. The film demonstrates, via short scenes showing Veronica writing in her journal that are accompanied by her narration, Veronica’s alienation from the Heathers with which she has allied herself: ‘Dear Diary’, she tells us in her first voiceover, ‘I want to kill, and you have to believe it’s for more than just selfish reasons. More than just a spoke in my menstrual cycle [….] I understand that I must stop Heather [….] Killing Heather would be like stopping the Wicked Witch of the West’. Veronica is then seduced, both physically and ideologically, by JD (Jason Dean – James Dean – Juvenile Delinquent), who embroils her in a plot to kill the Heathers and other bullies within the school. Finally, Veronica is forced to confront her complicity in the behaviour of both the Heathers and JD, taking a stand against JD at the end of the picture: ‘You’re not a rebel’, she tells him, ‘You’re fucking psychotic!’ (‘You say tom-ay-to, I say tom-ah-to’, is his response.) As JD tells her, ‘You believed it [his assertions that the pranks he is playing are harmless] because you wanted to believe it. Your true feelings were too gross and icky for you to face’. Emanuel Levy suggests that Veronica’s change of heart in the final third of the film results in a picture that ‘loses its nerve’ and ‘isn’t as cynical as it appears’: ‘Veronica is reestablished as a “nice” girl in a turnabout that isn’t convincing and undermines the film’s sardonic style’ (Levy, op cit.: 267). (Levy neglects to engage with the fact that Veronica is suckered by JD into participating in the murders, in each instance believing that the outcome of the pranks he and she are playing on their victims will be less than deadly.) In his script’s focus on the relationship between JD and Veronica, and how JD makes Veronica complicit in murder, Waters was reputedly influenced by one of his favourite films, Noel Black’s Pretty Poison (1968), in which a troubled young man (Anthony Perkins) convinces a girl (Tuesday Weld) that he is a secret agent. Perkins enlists Weld’s help in his ‘missions’ for the CIA, making her increasingly complicit in his world of violence. (The title of the novel on which Pretty Poison was based, the 1966 book She Let Him Continue by Stephen Geller, has an equal relevance for Heathers.)  As JD, Christian Slater delivers a performance that, like a number of Slater’s roles during this era, seems to channel the mannerisms of a young Jack Nicholson. From his first appearance, wearing a distinctive black overcoat amidst the flurry of colour in the school cafeteria, JD is a disruptive presence within the school. He’s a trickster-like character whose gleeful application of violence in the service of his desire of ridding the school of ‘unwanted’ elements – bitches, bullies and jocks, principally – anticipated the ‘manifesto’ of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold by approximately ten years. After Columbine, the scenes of JD terrorising two jocks with a gun he has managed to carry onto the school premises, and the finale in which JD plots an apocalyptic end to the school’s pep rally by planting bombs in the boiler room of the school, seemed frighteningly prescient – a perception compounded by the similarities between JD’s costume and the black trenchcoats worn by Harris and Klebold. ‘When our school blows up tomorrow, it’s gonna be the kind of thing to infect a generation’, JD asserts prophetically towards the climax of the picture, ‘I mean, it’s gonna be a Woodstock for the Eighties’. If the Heathers are products of privilege who represent slaves to conformity and consumerism, JD initially seems to embody the antithesis of this; however, the film eventually establishes JD’s status as a child of privilege too – the son of a minor magnate within the construction industry whose sociopathic delight in staging ‘accidents’, designed to rid him of those who stand in his way, has clearly influenced his son’s worldview. Like Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho, published two years after Heathers’ release, in 1991, Heathers offers a critique of a culture of ‘me first’ consumerism and conspicuous consumption that has, in the years since its original release, become the dominant paradigm. As JD, Christian Slater delivers a performance that, like a number of Slater’s roles during this era, seems to channel the mannerisms of a young Jack Nicholson. From his first appearance, wearing a distinctive black overcoat amidst the flurry of colour in the school cafeteria, JD is a disruptive presence within the school. He’s a trickster-like character whose gleeful application of violence in the service of his desire of ridding the school of ‘unwanted’ elements – bitches, bullies and jocks, principally – anticipated the ‘manifesto’ of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold by approximately ten years. After Columbine, the scenes of JD terrorising two jocks with a gun he has managed to carry onto the school premises, and the finale in which JD plots an apocalyptic end to the school’s pep rally by planting bombs in the boiler room of the school, seemed frighteningly prescient – a perception compounded by the similarities between JD’s costume and the black trenchcoats worn by Harris and Klebold. ‘When our school blows up tomorrow, it’s gonna be the kind of thing to infect a generation’, JD asserts prophetically towards the climax of the picture, ‘I mean, it’s gonna be a Woodstock for the Eighties’. If the Heathers are products of privilege who represent slaves to conformity and consumerism, JD initially seems to embody the antithesis of this; however, the film eventually establishes JD’s status as a child of privilege too – the son of a minor magnate within the construction industry whose sociopathic delight in staging ‘accidents’, designed to rid him of those who stand in his way, has clearly influenced his son’s worldview. Like Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho, published two years after Heathers’ release, in 1991, Heathers offers a critique of a culture of ‘me first’ consumerism and conspicuous consumption that has, in the years since its original release, become the dominant paradigm.

Video

Presented in a 4k restoration from the original negative, Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Heathers uses the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and is uncut, running for 103:02 mins. Taking up 33Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Presented in a 4k restoration from the original negative, Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of Heathers uses the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1 and is uncut, running for 103:02 mins. Taking up 33Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The level of detail is excellent throughout, close-ups containing plenty of fine detail complemented by an organic grain structure that is carried by a consistently strong encode. Damage is non-existent. Contrast levels are supremely well-balanced. Rich midtones offer plenty of definition and are balanced by an even shoulder and subtle gradation into the toe, with blacks that are deep and rich. The colour palette is naturalistic and consistent; some of the blue tones in the day-for-night filters seem noticeably amplified in comparison with previous home video releases (which would seem to be commensurate with the intentions of the filmmakers). In all, this is an excellent HD presentation of Heathers which is, in all respects, a huge improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases. Scroll to the bottom of this review for some full-sized screengrabs (please click to enlarge).

Audio

There are three audio options: (i) a LCPM 1.0 mono track; (ii) a LPCM 2.0 stereo track; and (iii) a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. The 5.1 track contains added sound separation, which is effective but of limited use in such a dialogue-heavy film; on the other hand, this newer 5.1 mix seems ‘muted’ in comparison with the other tracks. The mono track has good depth and range, whilst the stereo track offers a solid balance of the ‘oomph’ of the mono track and the ambience of the 5.1 track. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and free from problems.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with director Michael Lehmann, producer Denise Di Novi and writer Daniel Waters. - ‘Lehmann’s Terms’ (15:05). In a new interview, Lehmann reflects on how he became a filmmaker after committing himself to ‘getting an education first’ and then studying film ‘if I can’. Lehmann talks about his work up to Heathers and his intentions in making Heathers. He reflects on how difficult it is to get a ‘dark humoured film’ made, and he suggests that the best advice he can give younger filmmakers ‘is just make movies’. - ‘Pizzicato Croquet’ (11:11). Interviewed separately, David Newman (the composer of the film’s score) and Michael Lehmann talk about the music of Heathers and how they collaborated on scoring the picture. - ‘How Very: The Art and Design of Heathers’ (15:14). This new featurette sees input from Lehmann, the film’s production designer Jon Hutman and art director Kara Lindstron. Interviewed separately, the participants talk about the aesthetic of the film, discussing the mise-en-scène and some of the concepts in the visual design of the picture – for example, the idea to ‘colour code’ the Heathers. - ‘Casting Westerburg High’ (11:35). The film’s casting director, Julie Seltzer, is interviewed about the casting process for the picture. Seltzer discusses her background and how she came to be involved in casting for films (her first picture was Grease 2). She talks about the requirements for a good casting director, suggesting that they should have an ‘acting, directing or theatre arts background’ to enable them to relate to the actors – and to understand ‘what that person’s capable of’.

- ‘Poor Little Heather’ (17:41). Actress Lisanne Falk offers her memories of the film in a new interview. Falk talks about some of her other roles. She was offered the role of Heather McNamara after another actress was cast but was found not to be ‘working’ for the role. Falk also reflects on her decision to retire from acting in the early 2000s. - ‘Scott and Larry and Dan and Heathers’ (38:27). Writer Daniel Waters speaks with screenwriting duo Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski. It’s a relaxed, fascinating conversation in which the three practitioners reflect on their approach to writing for films and talk about their shared experiences in the filmmaking industry. - ‘The Big Bowie Theory’ (35:03). Actor/Comedian John Ross Bowie, an avowed fan of the film, talks about his long-standing love of Heathers. He recalls his first encounter with the film during its initial theatrical run, and he talks about some of the motifs within the film – notably the symbolic use of colours. - ‘Return to Westerburg High’ (21:21). This featurette was produced for the film’s release on DVD by Anchor Bay. It features input from Daniel Waters, Michael Lehmann and Denise Di Novi, who talk about the making of the picture and also reflect on some of the issues raised by the script, such as teenage suicide. - ‘The Beaver Gets a Boner’ (19:53). Made on 16mm in 1985 whilst he was studying at USC School of Cinematic Arts, Michael Lehmann’s student film features a similar high school setting to Heathers and is as darkly comic as Lehmann’s later feature film – opening with a young Boy Scout buying a heroin kit on a playground. It’s an impressive (and inspirational) film for a student production. - Lethal Attraction (Heathers) trailer (2:55). - 30th Anniversary rerelease trailer (1:45). - Image Gallery (2:55).

Overall

Emanuel Levy notes that Heathers begins as an ‘ordinary school romp’ but evolves into ‘a mean-spirited sitcom’ that extends its story ‘into the realm of the perverse’ (Levy, op cit.: 267). The film’s dialogue is sharp but the editing is sometimes even sharper: when Heather McNamara asks Veronica to go on a double-date with herself, Kurt and Ram, Veronica reluctantly agrees, ‘As long as it’s not going to be one of those nights where they get shit-faced and take us to a pasture to tip cows’. Lehmann cuts from this to… a pasture where a drunken Kurt and Ram giggle as they prepare to ‘tip’ a bovine. Amidst this, the film contains some wonderful allusions for cinephiles: JD’s murder of Kurt and Ram in the woods has subtle echoes of the botched assassination in Bertolucci’s Il Conformista (1970), and Veronica’s attempt to convince JD that she has committed suicide by hanging references Hal Ashby’s Harold & Maude (1971). Emanuel Levy notes that Heathers begins as an ‘ordinary school romp’ but evolves into ‘a mean-spirited sitcom’ that extends its story ‘into the realm of the perverse’ (Levy, op cit.: 267). The film’s dialogue is sharp but the editing is sometimes even sharper: when Heather McNamara asks Veronica to go on a double-date with herself, Kurt and Ram, Veronica reluctantly agrees, ‘As long as it’s not going to be one of those nights where they get shit-faced and take us to a pasture to tip cows’. Lehmann cuts from this to… a pasture where a drunken Kurt and Ram giggle as they prepare to ‘tip’ a bovine. Amidst this, the film contains some wonderful allusions for cinephiles: JD’s murder of Kurt and Ram in the woods has subtle echoes of the botched assassination in Bertolucci’s Il Conformista (1970), and Veronica’s attempt to convince JD that she has committed suicide by hanging references Hal Ashby’s Harold & Maude (1971).

In its study of the stifling atmosphere of the American high school, in retrospect Heathers seems like a logical progression from Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and stands in stark relief against many of the other high school-set pictures of the 1980s. As JD says in the film itself, ‘The extreme always seems to make an impression’. Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation of Heathers contains an excellent presentation of the main feature, sourced from a new 4k restoration based on the film’s negative, and is accompanied by a superb range of contextual material. Fans of Heathers will want to buy this Blu-ray release, or else no-one will let them play their reindeer games (whatever that means). References: Goodall, Nigel, 1998: Winona Ryder: The Biography. Blake Publishing Levy, Emanuel, 1999: Cinema of Outsiders: The Rise of American Independent Film. New York University Press Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|