|

|

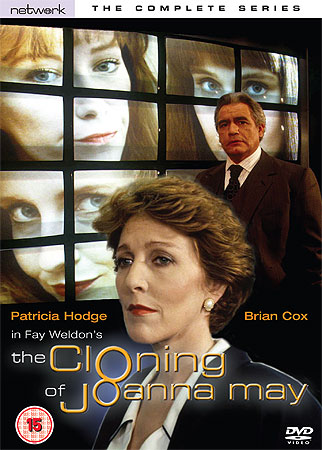

Cloning of Joanna May (The) (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (16th January 2009). |

|

The Show

Part One (78:55) Part Two (78:51)

Produced for Granada Television in 1992, this adaptation of Fay Weldon’s novel was directed by Philip Saville, a former actor and veteran director of British television drama. Within the genre of British television drama, Saville is considered something of a pioneer, thanks to the dynamic and intricately-planned camerawork of many of the episodes he directed for ITV’s Armchair Theatre (1956-1968) strand in the 1950s and 1960s, including the acclaimed 1960 adaptation of Harold Pinter’s ‘A Night Out’. Saville was also one of the first television directors to use videotape for location shooting, with his work on the BBC’s Hamlet at Elsinore (1964), the groundbreaking adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet shot on location at Kronborg Castle in Denmark. In his contribution to the BBC’s experimental drama strand Six (1965), ‘The Logic Game’, Saville was also one of the first directors to shoot a television play wholly on film, rather than the traditional mixture of filmed location work and videotaped studio footage. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, Saville delivered television plays for both the BBC’s Wednesday Play (1964-1970) and Play For Today (1970-1984) strands, including ‘Gangsters’ (1975), a gritty exploration of crime and racial tension in Birmingham which eventually evolved into a twelve-part series that was broadcast between 1976 and 1978. Saville also worked in genres such as science-fiction: in 1966, he directed an adaptation of E. M. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’ for the BBC’s Out of the Unknown (1965-1971) series. Although Saville also directed several commercially-released feature films (including Metroland in 1997), his most famous work is probably the BBC adaptation of Alan Bleasdale’s Boys From the Blackstuff (1982). Saville also directed the 1986 BBC adaptation of Weldon’s novel The Life and Loves of a She-Devil, which was adapted for the screen by the playwright and telewriter Ted Whitehead. Whitehead and Saville collaborated again for Granada Television’s 1992 adaptation of Weldon’s 1989 novel The Cloning of Joanna May. They were reunited with the actress Patricia Hodge, who had taken a starring role in The Life and Loves of a She-Devil as Mary Fisher, the novelist who is the object of Bobo’s (Dennis Waterman) infidelity and thereby incurs the wrath of Bobo’s wife Ruth (Julie T. Wallace). In The Cloning of Joanna May, Hodge plays the titular character, who has been separated from her husband Carl (Brian Cox) for ten years. Carl is the Chief Executive of Britnuc, a private company which, thanks to the privatisation of the energy industries that took place in Britain during the 1980s, has control of its own nuclear power plant. Whilst Carl very publicly lobbies for the public’s acceptance of nuclear energy and parades with his younger mistress Bethany (Siri Neal), Joanna fools around with her toyboy lover Oliver (James Purefoy). However, both Joanna and Carl obsess about one another: Joanna has hired Mavis (Billie Whitelaw) to pry into Carl’s private life, and Carl reveals to Bethany that since his separation from Joanna he has remained celibate.

It is revealed that Joanna and Carl’s relationship came to an end when Joanna had an affair with Isaac (Peter Capaldi), an Egyptologist who was employed by the gallery that Carl had bought simply for the ‘status’ it brought. Joanna declares that Isaac was a ‘sensitive, spiritual person who taught me about things that Carl knew absolutely nothing about’; to Bethany, Carl dismisses Isaac’s status and philosophy, stating that ‘I wouldn’t have minded if he was richer or more important than me’ and asserting that Isaac ‘filled her [Joanna’s] head with all sorts of mystical rubbish, even taught her the tarot pack. She said it derived from the Egyptian Book of Toth. “Book of Tosh”. Gobbledygook’. Following his discovery of the affair between Joanna and Isaac, Carl had Isaac discretely ‘offed’ in a hit-and-run incident; later, the still jealous Carl has Oliver killed by a gang of bikers. Joanna sheds tears for Oliver, even though she did not love him, until the point that the investigating detective reveals to her that Oliver was bisexual and was under investigation for a sexual offence involving a schoolboy.

When Joanna confronts Carl in front of Bethany, Carl tells Joanna that ‘You destroyed my faith in women a long time ago’. Joanna bitterly declares that in 1969 Carl made her abort their child, but Carl reveals that he had a vasectomy at the age of 18 and that Joanna had not really been pregnant: she had suffered a phantom pregnancy, and the abortion procedure was simply a pantomime that had been staged for her benefit. However, Carl also reveals that during the procedure he began steps to clone Joanna using DNA from one of her eggs, and in 1969 four clones of Joanna were born; one of the clones died, but three are still in existence. With this information, Joanna seeks to ‘possess’ her clones, seeing it as her right to claim ownership over them. Meanwhile, Carl plans to gather the clones together in his country mansion, to determine which of them will become his future wife.

Writing about Weldon’s novel The Cloning of Joanna May in the St Petersburg Times, Kitty Benedict states that ‘The large issues are her concern: male set against female, the looting and pollution of the world and of the soul, power and weakness, sense and senselessness. Her mordantly black view of things sets the tone, yet the energy beneath returns one to some sort of stubborn optimism’ (Benedict, 1990: en). One of the ‘large issues’ at the centre of the novel and the television adaptation is the effect of ‘inhuman’ sciences such as cloning and nuclear energy. The private drama of Carl and Joanna’s relationship (and the reveal of Carl’s plot to clone Joanna) is played out within the broader context of Carl’s company’s attempts to push the profile of their privately-owned nuclear power plant. Interspersed throughout the narrative are scenes in which Carl addresses the press, first attempting to assuage the public’s concerns over nuclear power (stating that ‘Nuclear power will save us from the sun. Nuclear power will save us from nature’) and later, during a television appearance, becoming visibly angered at what he perceives to be the public’s ignorance over the benefits of nuclear power and their obsession with its potential dangers. This culminates in the closing sequence of the television adaptation, in which Carl and a bikini-clad Bethany make preparations to swim in the waters that have been used to cool the nuclear plant (in the novel, Carl even goes so far as to drink a glass of radioactive milk on television). The privatisation of the energy industries (and the concomitant push for nuclear power) that had occurred under Thatcher’s reign as Prime Minister were a hot topic in the 1980s and early 1990s, especially in light of the accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl. In 1989, the year Weldon’s novel was published, the British electricity industry had undergone a radical restructuring (following the 1989 Electricity Act), which led to the creation of twelve distinct regional electricity companies. There was a greater push for nuclear energy from both industry and the government, although in reality the government did not privatise its nuclear power stations until 1996; but this commerce-driven push for nuclear power was combated by increased public fears about nuclear energy that had been triggered by the events in Chernobyl. Weldon’s representation of a private company owning a nuclear power plant was, in 1989, pure speculation; but at the time of the novel’s publication (and the television adaptation, two years later) her immediate concern for the effects of privatisation were extremely topical.

In light of his association with a set of values that most people would, at the time, have found problematic, it would be easy for Weldon and Whitehead to represent Carl as a cold-hearted and misogynistic businessman, especially considering the way in which he despatches both Isaac and Oliver. However, in both the novel and its television adaptation neither Carl nor Joanna are presented completely sympathetically, whilst neither character is presented as a villain. To counter Carl’s sometimes cold actions, it is revealed that Carl was born in Lithuania but emigrated to Britain as a child, where he suffered an abusive childhood and was raised in a kennel with ‘a bitch and her pups’. The experience of his childhood led him to distrust women, and he tells Joanna that ‘My mother made me vicious, but you restored my faith in woman; and then you betrayed that faith. You made me […] destructive, and I can never forgive you. To err is human; to forgive divine; and I am not Jehovah’. Bethany is also surprised to learn that despite his public image as a playboy, Carl has only managed to forge two intimate relationships in his life, with Joanna and then with Bethany herself. It is clear that whatever her intentions and however she tries to justify her actions, Joanna’s infidelity has consolidated Carl’s isolation and his inability to connect with other people, especially women. Perhaps due to his negative experiences with women and despite his open criticism of idealists, Carl idealistically seeks to create the perfect woman. When he discovers that the clones of Joanna are flawed, fickle and riddled with vanity, he disappointedly states that ‘I thought I’d create a perfect woman, one who looked, listened, understood and was faithful. But it’s hopeless; they are spoiled, sullied, imperfect. I thought genetic science could improve on nature, but nature has its own course—randy, riotous, purposeless nature [….] The whole world is one filthy stinking kennel and all that matters is sex and food. That’s reality’. To Joanna, he rationalises his decision to create clones of her as a means of revisiting an earlier, more ‘pure’ relationship: he seeks to reconnect with her, ‘[n]ot as you are now, but as you were when you were young, free from the stain of betrayal. What man has not dreamt of the springtime of his love, of his one true love, when it was true and innocent and pure?’ Eventually, Carl is forced into the realisation that his idealised view of Joanna (ie, the Joanna that existed before she betrayed him with Isaac) may never have existed; after observing the fickle and spiteful behaviour of Joanna’s clones, he tells them ‘You’re all chips off the old block, and the old block was rotten’. Likewise, Joanna is presented in an unsympathetic light. Early in the first episode, she tells Oliver ‘it’s a miracle what you can do with a jar of cream and an exfoliator’. Oliver tries to console Joanna by stating that ‘It [aging] happens to all of us’. However, Joanna demonstrates her shortsighted nature and hints at the vanity that one of her clones inherits by stating that, ‘Personally, I expected to live forever frozen in time, aged about 30’. Joanna also shows herself to be equally as possessive as Carl: when she discovers the existence of her clones, she aggressively declares that if the clones ‘belong to anyone, they belong to me. They’re clones of me. I want them, I need them, they’re mine’. However, she is manoeuvred into an epiphany regarding her own selfish behaviour when she discovers that one of the clones, a model, is (in the words of the photographer who has been vainly trying to get the model to smile) ‘a spoilt bitch’ who is ‘getting too big for her stilettos’.

Nevertheless, despite its criticism of Joanna, this adaptation of Weldon’s novel never loses sight of the fact that the characters exist in a patriarchal society, a culture driven by the needs of men. The series opens with Carl pining over an image of Joanna; in a monologue that openly alludes to the Freudian Madonna-whore complex, Carl opines ‘Joanna, my angel, my soul, my slut [….] my Empress, my Goddess, my Jezebel’. Carl has created two dualistic myths of Joanna: the Joanna that existed prior to her affair with Isaac (the idealised woman, the ‘angel’/‘Empress’) and the ‘slut’/‘Jezebel’ that betrayed him. This concept of womanhood is suggested to dominate throughout the society depicted in the narrative: when Carl asks one of his employees about the current state of Joanna’s clones, Carl’s employee declares that ‘They’re typical young women of today, sir: promiscuous at best, lesbian at worst’. Carl’s response is to chauvinistically suggest that ‘Perhaps they just haven’t met the right man’. Later, when talking to Joanna Carl reminds her that her clones ‘are young’; when Joanna reminds him that ‘you’re old’, Carl reminds her of the subordinate position of women within modern society: ‘But that doesn’t matter. Because I’m a man, and you’re only a woman. And the music stops for women long before it does for men. I am the Lord of the Dance, and I shall have you as my partner… Not as you are now, but as you were when you were young, free from the stain of betrayal’. In a further acknowledgment of the patriarchal order of marriage and the way in which it forces women into a subservient role, Joanna suggests to another character that ‘Loving Carl, I lost my identity; I lost my self’.

As Kitty Benedict claimed in her review of Weldon’s novel, in The Cloning of Joanna May ‘[a]s bad as the men are, the women play all sorts of tricks, too, to conform to what the world and men expect of them. They fool themselves as much as the men do with their powerful tools and toys: money, violence, power, murder’ (op cit.). However, as Entertainment Weekly noted in its review of the novel, by the time of the publication of The Cloning of Joanna May Weldon’s ‘battle of the sexes’ theme had suffered from overexposure: describing the novel as ‘a chilly scenario of the innate incompatibility of man and woman’, the article suggests that ‘[b]y now even Weldon must be tiring of her war-between-the-mates outline’ and describes the novel as a ‘rehashed recipe of preternaturally cold characters acting out a litany of nastiness. Husbands hate wives, mothers hate daughters, men are messianic, and God has fled’ (EW, 1990: en.). It’s difficult not to see this adaptation as a pale imitation of The Life and Loves of a She-Devil, although to be fair the satirical representation of the nuclear power industry enriches this particular television drama; however, this is given relatively little screen time, and in the second part of the drama is relegated to the background. Nevertheless, despite Entertainment Weekly’s admittedly honest criticism of Weldon’s novel, this television adaptation is never less than watchable, thanks largely to the performances of Cox and Hodge and the direction of Saville. Like the novel it is based on, this television adaptation sometimes seems to lose focus due to its attempts to meld together the private melodrama of Carl and Joanna’s relationship within the broader context of the debate about nuclear power, but Whitehead’s teleplay paints in less broad strokes than Weldon’s novel and is more focused because of it.

Video

The Cloning of Joanna May is presented in its original aspect ratio of 4:3. Shot on film, the series has an expensive-looking aesthetic that is well-presented on this DVD release.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monophonic audio track. Dialogue is clear, and the track is problem-free. There are no subtitles.

Extras

There is no contextual material, which is a little sad as the show could benefit greatly from some attempt to place it in context, especially in relation to the then-contemporary debates about the privatised energy industries—which may be lost on modern-day first-time viewers.

Overall

Fans of quality television drama will welcome this DVD release, as it contains a little-seen drama starring three of Britain’s best-loved actors, Pat Hodge, Brian Cox and Billie Whitelaw. As noted above, the drama is very much of its time in some of its themes (eg, its satire of the energy industries) but as relevant as ever in some of its other themes (the exploration of the relationships that exist between men and women, and, notably, the issue of cloning—which is more relevant now than it was in 1992). Whilst not as good as Whitehead and Saville’s earlier adaptation of Weldon’s The Life and Loves of a She-Devil, The Cloning of Joanna May is definitely worth two-and-a-half hours of anyone’s time. References: Benedict, Kitty, 1990: ‘High-tech war between the sexes: Fay Weldon's entertaining new novel pushes against creative limits’. St Petersburg Times (25 March, 1990) EW, 1990: ‘Book review: The Cloning of Joanna May by Fay Weldon’. Entertainment Weekly (30 March, 1990)

|

|||||

|