|

|

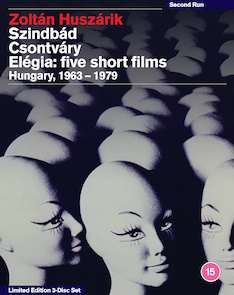

Zoltán Huszárik: Szindbád/Csontváry/Elégia: Five Short Films - Limited Edition

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Second Run Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (17th August 2025). |

|

The Film

"Zoltán Huszárik is one of the great unsung masters of international cinema. With an output that comprised just two features and a handful of remarkable short films, his unique and beautifully realised works set him apart from all other contemporary filmmakers, creating an intoxicating body of work unlike any other in modern cinema. This special edition 3-disc Blu-ray box set contains his two features Szindbád and Csontváry, plus five of his acclaimed, rarely seen short works - including his most renowned film poem, Elégia - presented from new 4K restorations and released for the first time ever on Blu-ray. With this release, one of Hungary’s best-kept cinematic secrets finally has a chance to flourish." Josef von Sternberg Award: Zoltán Huszárik (winner) - Mannheim-Heidelberg International Filmfestival, 1972 Szindbád: Whereas Sindbad the Sailor sailed the seven seas in search of adventure, Szindbad the seducer (Trip Around My Cranium's Zoltán Latinovits) travels through the cafes, restaurants, brothels, and bedrooms of turn-of-the-century Hungary conquering women. Young, old, rich, poor, beautiful, ugly, flighty, neurotic, respectable, Szindbad samples all of them. When we first meet him, he is dead, packed off into the back of a horse-drawn cart and sent "home" but his body is rejected as the horses makes stops at the residences of past lovers (one of whom steals his winter coat before sending him off). Through a series of non-linear episodes - with only a gesture, a word, or a phrase to suddenly transition from one to another - we meet several of his past loves both in the past and the present (and we are in doubt as to the veracity of any of them since Szindbad himself says "Life is a chain of beautiful lies" and his recollections are meant to bring him pleasure). Some of the women have wised up (and are even able to provide Szindbad himself with insight into his own character), while others have carried the torch even though they have married and settled down. The numerous encounters advance no plot, they merely add layer upon layer to Szindbad's character, whose pursuit of sensation has not left him happy; as he seduces one woman, he's either thinking of the next or the one before (he even abandons a wealthy older woman - who has told him that she is willing her fortune to him - in favor of another conquest). His end finds him literally and figuratively without a home to rest. Based on the semi-autobiographic character created by Gyula Krudy, and incorporating episodes from his supposedly unfilmable stories – where a little bit of incident usually serves as a launch point for Krudy's musings which reportedly anticipate James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Virginia Woolf among others – Szindbad was the first feature-length film of director Zoltan Huszárik and it has since kept its place in polls over the years of the best Hungarian films. The film opens up with a montage of rapidly cut details of oil floating in water, stands of blond hair, a budding rose, melting snow, water dripping off tree bark that are revealed to be motifs associated with each woman. As each appears again on screen throughout the picture, we are carried one step closer to Szindbad's end: the last of his conquests we see - which may be the first - takes place on a frozen lake, which reminds us of the snowy terrain through which Szindbad's dead body is carried by the horses. Sadly, Huszárik would never eclipse this film. His big budget film on the life of painter Csontváry - in which Latinovits was to star before his death, a possible suicide or tragic accident - was a failure and he would die a year later at age fifty. Golden Spike (Best Film): Zoltán Huszárik (nominee) - Valladolid International Film Festival, 1980 One of the first Hungarian painters to gain wider recognition and indeed considered by Hungarian critics to be their country's greatest avant-garde artist, Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka regarded painting as a spiritual calling – traveling the world in search of beauty and truth before picking up a brush, shunning publicity, and eventually retiring in the mountains to paint cedars – and an actor (Late Full Moon's Itzhak Finzi) tasked with playing him on the stage also regards intrepreting genius his own life's mission with the conviction that creatives who are otherwise "split apart by the energy of their genius" are the future of Hungarian culture. The actor intensely studies Csontváry's paintings and either physically or mentally visits the sites of his world travels. Dogged by a stranger (The First Two Hundred Years of My Life's István Holl) who might be one of the mental patients at the sanatorium where his wife works, or perhaps the very spectre of his own mental deterioration, the actor is riddled by doubt and a periodic "imposter syndrome" that has him occasionally visiting his worried mother (A Nice Neighbor's Margit Dajka) for coddling and his estranged wife Anna (Red Psalm's Andrea Drahota) and son whenever he ponders the possibility of a more mundane existence, always alienating them until all that is left in his life are the roles he has played including the still-elusive Csontváry. Nine years after the domestic success of Szindbad which propelled him domestically (but not internationally) to the level of more prolific colleague Miklos Jancsó (The Red and the White), and with only a few shorts and television projects in between, Huszárik chose Csontváry as the subject of his long gestating sophomore (and final) feature film initially with Szindbad's Zoltán Latinovits in mind for the lead before he either fell or jumped in front of a train in 1976 (Michael Brooke's essay in the included booklet mentions the similarity of the circumstances of his death and that of poet Attila József whose work Latinovits had interpreted on the stage). Despite the actor identifying himself as such, the framing is not readily apparent with at least this reviewer at first believing it was Csontváry describing himself figuratively and his resume as a long series of roles meaning that he was a different person creating each of his works when expected to "explain" his work to the public; however, the modern day Hungary setting – however largely pastoral – becomes more apparent, and director Huszárik manages to simultaneously conveys both his and the actor's attempt to understand and interpret Csontváry and a nuanced characterization of the actor who simultaneously seems earnest in his work while using it as an excuse to neglect his marriage and family with his wife already checked out of their union and seemingly capable of financially supporting herself and her son as her husband drops in and out of their lives, approaching real life like a dilettante as he suggests working with his wife at the sanatorium, wandering around the patients, entertaining them with his violin, and forming a connection with his wife's colleague (Mephisto's Ágnes Bánfalvy) which calls into question his fidelity elsewhere as the admirers who believed him to be a real painter that he snubbed may already have shared his bed. One is never quite sure if in some of the travel scenes we are seeing Finzi as the actor retracing the artist's steps or Finzi as Csontváry and which of his surreal hallucinations are those of the artist or those of the actor interpreting meaning behind the artist's work from the perspective of his own mental illness. Csontváry suffered auditory hallucinations while the actor may may or may not have delusions of grandeur but also seems to be having a nervous breakdown as his own hallucinations incorporating the imagery of the artist seems to equate normality with living death (as in a sequence where the actor is stuck behind a fence that turns a series of mannequins posed in a forest clearing into a composition that is ruptured by a wild dog that tears one of the figures into pieces while the actor can only watch). Despite having only a faint likeness to Finzi, the viewer might actually believe Holl is the actor's doppelgänger in a creative shot in which Finzi is replaced not by a double as one expects in scenes with an actor playing twins but by a wax mannequin likeness as Holl circles around him. The final sequence sees the actor old and stooped over – or made up to look like an old man in another role – in a gallery of paintings of the roles he has played. When the actor comes upon the Van Gogh-like self-portrait of Csontváry, likenesses of figures from the artist's paintings – played by notables from Hungarian cinema and theater – collide in a swimming pool orgy where reproductions of the artist's work are tossed, torn, and sink below the surface. It is difficult to determine just what the film wants to say about the artist apart from suggesting that the calling of an artist may be spiritual but looked upon by the outside world as escapist and contrarian, but the structure of this film more so than Szindbad gives Husarik license to employ several experimental touches including time-lapse photography (and reverse time-lapse photography it seems), slow motion, the passage of time through staging within long takes, and so on in a manner that seems more haphazard than Andrei Tarkovsky's comparatively disciplined visualization of life "around" painter Andrei Rublev but all the more frustrating because – despite the gorgeous photography of Huszárik's regular cinematographer Péter Jankura and the momentous scoring of Miklós Kocsár (The Golden Head) – it is only as compelling in fits and starts.

Video

Szindbád had been regularly available on physical media in its native Hungary but first became accessible to English-speaking audiences on DVD in 2011 from a then-recent digital restoration. Second Run has upgraded their DVD to Blu-ray utilizing a newer 4K restorations by the National Film Institute Hungary - Film Archive. The 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.85:1 widescreen transfer maintains the film's bygone look with softish medium and wide shots contrasting with sharper macro close-ups – even with special lenses and even a camera attached to a microscope, the behind the scenes material reveals that some of the details were simulated – that emphasize the sensory nature of the film's atmosphere in keeping with Krudy's literary style. There is a subtle yellow cast to the whites compared to the DVD but this may indeed be more accurate while the standard definition digital master may have been timed to get cleaner whites at the expense of slightly diluted blacks. Csontváry's 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.66:1 widescreen Blu-ray also comes from a new 4K restoration and fares best during its unambiguously contemporary scenes of the actor's domestic life while Huszárik and cinematographer Jankura deploy various techniques to flashbacks and visions including some filters in front of the lenses, capturing natural back-lighting, the always effective shafts of light through floating dust, and time-lapse with the sometimes jarring presence of sharper close-ups as in the misty forest scene of mannequins in period dress witnessed by the actor cutting to the crisp close-up of one such mannequin as it melts before the actor's eyes.

Audio

Szindbád features a crystal clear Hungarian LPCM 2.0 mono track. Everyone is post-dubbed and the dialogue is always intelligible. The sound design is less realistic or naturalistic, supporting the subjective and sensory aspects of the storytelling along with the music which weaves in and out of the film rather than being slathered over it. We have not compared the subtitles to the DVD but the back cover note that the translation is "new and improved." Csontváry also has a post-dubbed Hungarian LCPM 2.0 track – Bulgarian actor Finzi did not speak any Hungarian so he is dubbed here by Ádám Rajhona (Jakob the Liar) and the mixers do make a good effort of making it sound like Finzi projecting "his" voice during his monologues whether in an empty theater or out in nature – and once again the sound design is less naturalistic apart from some sequences set in crashing waves or the sanatorium. The scoring is more dominating here than in Szindbád, perhaps because it underlines visions of madness rather than tenuous memory. The optional English subtitles are free of any noticeable errors.

Extras

Extras for Szindbád start off with the DVD edition's "Szindbád: An Appreciation" (12:48) in which filmmaker Peter Strickland (The Duke of Burgundy) likens Huszárik's techniques to Nicolas Roeg and Stan Brakhage and wishes he had seen the film before he made his directorial debut. "The World of Krúdy and Huszárik" (21:52) is a discussion on the collaboration between writer Krúdy and director Huszárik in which the commentators discuss how the latter transposed the latter's art nouveau literary style with its emphasis on sensory detail and atmosphere to the cinematic language of montage and associative editing as well as the parallels between Huszárik making such a "decadent" film at a time when his contemporaries were focusing on social realism with Krúdy eschewing the predominating contemporary modes of the psychological novel or social problems, with both possibly ironically addressing their disillusionment with their transitional time periods. "Huszárik and Contemporary Music" (23:38) is an interview with composer Zoltán Jeney (My Way Home) who first worked with Huszárik on the short Capriccio and discusses some of the techniques employed like recording natural sounds on magnetic tape, cutting it up and then remixing it. In discussing Szindbád, Jeney discusses how using music for both realistic and psychological effect rather than just accompaniment, degrading cleanly-recorded music for phonograph play, recording different instruments to give a sense of distance and direction within the scene (even though the film is in mono), and scoring Szindbád's death scene in the church with the sounds of organ pipes as they run out of air. "Inside the Popular Science Film Studio" (2:29) is a 1972 newsreel looking primarily at the film's macro and micro photography and the different materials used to achieve certain effects like the globules of oil in the soup which if real would have solidified immediately. Csontváry has fewer extras but they are nonetheless interesting. "Who is Zoltán Huszárik?" (10:20) is brief but provides an overview of Huszárik's work (noting that his experimental and risky impulses came from studying at the Béla Balázs Studio). "Making Csontváry" (3:15) is a 1979 behind the scenes newsreel covering the film as it is screened at the Hungarian Film Festival and provides some more useful detail about the climax, noting the militaristic figures are those of defeated Austro-Hungarian army and identifies the actor playing Franz Josef as veteran Samu Balázs (Late Season). The third disc in the set is titled Elégia - Five Short Films by Zoltán Huszárik and features five of his seven short films excluding his first one Játék from 1965 and his piece on Hungarian sculptor Amerigo Tot from 1970 as well as his television shorts. "Groteszk" (1963; 11:50) is the most "conventional" of the five in that it actually has scripted dialogue and longer takes rather than the montage of his features, "Elégia" (1966; 21:03) which sees more of an emphasis on montage as it examines the relationship between man and horse from the rural past to the urban present, "Capriccio" (1969; 17:47) which is an amusing piece featuring a snowman posed and redressed over a succession of shots, while the subjects of "Homage to Old Women [Tisztelet az öregasszonyoknak]" (1972; 13:11) are primarily war widows, and "A Piacere" (1976; 22:20) visits cemeteries in various countries examining their monuments (along with one real train wreck of a funeral with drunken and fainting mourners nearly toppling into the grave while tossing in mementos as the coffin is still being lowered).

Packaging

Michael Brooke's booklet from the DVD edition of Szindbád has been newly-revised, moving and reworking some material to the Csontváry booklet while expanding discussion of Krudy, Huszárik's schooling and early short films – including presumably new access to materials like Huszárik's treatment to Elégia – star Latinovits, and the film's lasting popularity in Hungary. Also added to the booklet is an essay and drawings by Huszárik from 1971. The booklet on Csontváry discusses parallels with Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev and likens the structure of the film to Ken Russell's BBC television project The Debussy Film as well as sheds light on some details that might be lost to those of us with little knowledge of Hungarian history. Most interestingly, in discussing Latinovits' death, Brooke notes some of the other actors Huszárik approached and makes the case that an actor of Latinovits' stature with Hungarian audiences would have more effectively sold the "Latinovits-like complications" (as one critic described it). No booklet accompanies the shorts disc but some of them are discussed within the Brooke essays.

Overall

Second Run's three-disc set Zoltán Huszárik: Szindbád/Csontváry/Elégia: Five Short Films encompasses nearly the entire career of one of Hungary's major but now almost forgotten filmmakers who had one iconoclastic hit and one major flop, losing his onscreen alter ego in between and only now getting another shot at international recognition nearly a half-century after his death.

|

|||||

|